American Negotiating Behaviour Towards Nuclear Rogue States

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

DIRECTING the Disorder the CFR Is the Deep State Powerhouse Undoing and Remaking Our World

DEEP STATE DIRECTING THE Disorder The CFR is the Deep State powerhouse undoing and remaking our world. 2 by William F. Jasper The nationalist vs. globalist conflict is not merely an he whole world has gone insane ideological struggle between shadowy, unidentifiable and the lunatics are in charge of T the asylum. At least it looks that forces; it is a struggle with organized globalists who have way to any rational person surveying the very real, identifiable, powerful organizations and networks escalating revolutions that have engulfed the planet in the year 2020. The revolu- operating incessantly to undermine and subvert our tions to which we refer are the COVID- constitutional Republic and our Christian-style civilization. 19 revolution and the Black Lives Matter revolution, which, combined, are wreak- ing unprecedented havoc and destruction — political, social, economic, moral, and spiritual — worldwide. As we will show, these two seemingly unrelated upheavals are very closely tied together, and are but the latest and most profound manifesta- tions of a global revolutionary transfor- mation that has been under way for many years. Both of these revolutions are being stoked and orchestrated by elitist forces that intend to unmake the United States of America and extinguish liberty as we know it everywhere. In his famous “Lectures on the French Revolution,” delivered at Cambridge University between 1895 and 1899, the distinguished British historian and states- man John Emerich Dalberg, more com- monly known as Lord Acton, noted: “The appalling thing in the French Revolution is not the tumult, but the design. Through all the fire and smoke we perceive the evidence of calculating organization. -

Quadrennial Diplomacy and Development Review 2015

ENDURING LEADERSHIP IN A DYNAMIC WORLD Quadrennial Diplomacy and Development Review | 2015 This QDDR is dedicated to the memory of the brave men and women of the State Department and the U.S. Agency for International Development—both American citizens and foreign nationals—who have given their lives while in the service of the United States overseas. We honor their sacrifice, which has helped make the world more peaceful, prosperous, and secure. MESSAGE FROM SECRETARY KERRY Today’s international landscape is more complex than ever before. The challenges we face are enormous, and so are the opportunities. They require us to keep faith with institutions like the State Department and USAID – with America – to ensure our ability to do the big things required to protect our interests and promote our values. And that means providing our diplomats and development professionals with both the willpower and the tools to accomplish the impossible. I want the QDDR to be the blueprint for the next generation of American diplomacy. I want our diplomats and development professionals to have the technology and know-how to confront both the challenges and the John Kerry opportunities. That’s why I launched the second QDDR United States Secretary of State last April. In the months that followed, hundreds of our offices and posts worldwide have engaged in exercises, focus groups, consultations, drafting and editing to help define and shape this document. From the outset, I asked our teams to avoid making this exercise all things for all people. A very smart Foreign Service officer told me when I first got here, “If everything’s important, nothing’s important.” So this QDDR does not seek to be everything to everybody. -

State - Germany 250/900/68/4- 12/22/2010

State - Germany 250/900/68/4- 12/22/2010 SUBJECT YEAR MONTH DAY PREFIX FROM TO * 62 10 12 KF010 AMCONSUL STUTTGART DEPT OF STATE * 73 10 16 O245 MOSCOW SECSTATE * 77 02 11 D005 SECSTATE MOSCOW * 78 02 23 E111 SECSTATE MOSCOW * 78 12 01 E112 SECSTATE AMCONSUL STUTTGART * 79 03 08 8 SECSTATE AMCONSUL STUTTGART * 79 03 28 P077 AMCONSUL STUTTGART SECSTATE * 79 07 17 E140 MOSCOW SECSTATE * 79 10 31 R238 SECSTATE BUCHAREST * 80 02 07 O329 SECSTATE USMISSION BERLIN * 80 06 04 R237 SECSTATE BONN * 80 06 06 E116 BERLIN SECSTATE * 80 06 24 D299 BERLIN SECSTATE * 81 07 02 D004 TEL AVIV SE/STATE * 82 01 08 R082-2 MOSCOW SECSTATE * 83 05 19 E069 SECSTATE USMISSION BERLIN * 83 07 26 D114 MOSCOW SECSTATE * 83 11 15 D023 SECSTATE MOSCOW * 84 08 28 E103 BONN SECSTATE * 84 08 29 E139 BONN SECSTATE * 84 10 15 D036 SECSTATE MOSCOW * 86 10 22 D219 SECSTATE BERLIN Page 1 State - Germany 250/900/68/4- 12/22/2010 SUBJECT YEAR MONTH DAY PREFIX FROM TO * 89 01 06 D039A BUCHAREST SECSTATE * 90 06 29 D144 SECSTATE LONDON * 91 09 11 D001 SECSTATE USOFFICE BERLIN * 92 02 21 D041 SECSTATE USOFFICE BERLIN * 92 03 27 R229 SECSTATE USOFFICE BERLIN * 92 05 20 D060 BONN SECSTATE * 94 06 06 D115 MOSCOW SECSTATE * 95 03 17 P162 BONN SECSTATE * 95 05 15 S063 BONN SECSTATE * 96 04 03 R205-2 BONN SECSTATE * 96 12 04 R203 BONN SECSTATE 12TH 94 06 24 L004 SECSTATE AMEMBASSY/LJUBLJAN COMPANY A 12TH 82 11 17 G052 SECSTATE AMEMBASSY/MOSCOW LUTHUANI 2ND/12TH 91 10 02 I021 SECSTATE AMEMBASSY/BONN LITHUANI ABARIS, 82 04 19 DE119 CHARLES GITTENS DONNA COOPER ANDRIUS ABARIS, 82 05 06 -

20 YEARS LATER Where Does Diplomacy Stand?

PUBLISHED BY THE AMERICAN FOREIGN SERVICE ASSOCIATION SEPTEMBER 2021 20 YEARS LATER Where Does Diplomacy Stand? September 2021 Volume 98, No. 7 Focus on 9/11, Twenty Years Later 22 Getting Off the X In a compelling personal account of the 9/11 attacks, one FSO offers tactics for surviving when catastrophe strikes. By Nancy Ostrowski 26 The Global War on Terror and Diplomatic Practice The war on terror fundamentally changed U.S. diplomacy, leaving a trail 39 of collateral damage to America’s readiness for future challenges. Intervention: FS Know-How By Larry Butler Unlearned Lessons, or the Gripes of a Professional 46 31 The State Department’s failure to Whistleblower effectively staff and run interventions Protections: America and 9/11: has a long history. Four critical A Nonpartisan The Real-World Impact of lessons can be drawn from the post-9/11 experience. Necessity Terrorism and Extremism As old as the United States itself, In retrospect, 9/11 did not foreshadow By Ronald E. Neumann whistleblowing has protections the major changes that now drive worth knowing about. U.S. foreign policy and national security strategy. By Alain Norman and 43 Raeka Safai By Anthony H . Cordesman From the FSJ Archive 9/11, War on Terror, Iraq 35 and Afghanistan FS Heritage The Proper Measure of the Place: 48 Reflections on the Diplomats Make Afghan Mission a Difference: Drawing from two tours, a decade The U.S. and Mongolia, apart, a veteran diplomat explores the competing visions for Afghanistan. 1986-1990 In the 1992 FSJ, Ambassador By Keith W. -

(CUWS) Outreach Journal #1145

USAF Center for Unconventional Weapons Studies (CUWS) Outreach Journal Issue No. 1145, 12 December 2014 Welcome to the CUWS Outreach Journal! As part of the CUWS’ mission to develop Air Force, DoD, and other USG leaders to advance the state of knowledge, policy, and practices within strategic defense issues involving nuclear, biological, and chemical weapons, we offer the government and civilian community a source of contemporary discussions on unconventional weapons. These discussions include news articles, papers, and other information sources that address issues pertinent to the U.S. national security community. It is our hope that this information resource will help enhance the overall awareness of these important national security issues and lead to the further discussion of options for dealing with the potential use of unconventional weapons. All of our past journals are now available at http://cpc.au.af.mil/au_outreach.aspx.” The following news articles, papers, and other information sources do not necessarily reflect official endorsement of the Air University, U.S. Air Force, or Department of Defense. Reproduction for private use or commercial gain is subject to original copyright restrictions. All rights are reserved. FEATURE ITEM: “Iran: Interim Nuclear Agreement and Talks on a Comprehensive Accord”. Authors; Kenneth Katzman, Specialist in Middle Eastern Affairs; Paul K. Kerr, Analyst in Nonproliferation; and Mary Beth D. Nikitin, Specialist in Nonproliferation. Published by the Congressional Research Service; 26 November 2014, 22 pages. http://fpc.state.gov/documents/organization/234999.pdf On November 24, 2013, Iran and the six powers that have negotiated with Iran about its nuclear program since 2006 (the United States, the United Kingdom, France, Russia, China, and Germany—collectively known as the “P5+1”) finalized an interim agreement (“Joint Plan of Action,” JPA) requiring Iran to freeze many aspects of its nuclear program in exchange for relief from some international sanctions. -

DEPARTMENT of STATE 2201 C Street NW., Washington, DC 20520 Phone, 202–647–4000

DEPARTMENT OF STATE 2201 C Street NW., Washington, DC 20520 Phone, 202±647±4000. Internet, http://www.state.gov/. SECRETARY OF STATE MADELEINE K. ALBRIGHT Chief of Staff ELAINE K. SHOCAS Executive Assistant DAVID M. HALE Special Assistant to the Secretary and KRISTIE A. KENNEY Executive Secretary of the Department Deputy Assistant Secretary for Equal DEIDRE A. DAVIS Employment Opportunity and Civil Rights Chief of Protocol MARY MEL FRENCH Chairman, Foreign Service Grievance Board THOMAS J. DILAURO Civil Service Ombudsman TED A. BOREK Deputy Secretary of State STROBE TALBOTT Under Secretary for Political Affairs THOMAS R. PICKERING Under Secretary for Economic, Business, and STUART E. EIZENSTAT Agricultural Affairs Under Secretary for Arms Control and JOHN HOLUM, Acting International Security Affairs Under Secretary for Management BONNIE R. COHEN Under Secretary for Global Affairs WENDY SHERMAN, Acting Counselor of the Department of State WENDY SHERMAN Assistant Secretary for Administration PATRICK R. HAYES, Acting Assistant Secretary for Consular Affairs MARY A. RYAN Assistant Secretary for Diplomatic Security PATRICK F. KENNEDY, Acting Chief Financial Officer RICHARD L. GREENE Director General of the Foreign Service and EDWARD W. GNEHM, Acting Director of Personnel Medical Director, Department of State and CEDRIC E. DUMONT the Foreign Service Executive Secretary, Board of the Foreign JONATHAN MUDGE Service Director of the Foreign Service Institute RUTH A. DAVIS Director, Office of Foreign Missions PATRICK F. KENNEDY, Acting Assistant Secretary for Population, Refugee, JULIA V. TAFT and Migration Affairs Inspector General JACQUELINE L. WILLIAMS-BRIDGER Director, Policy Planning Staff GREGORY P. CRAIG Assistant Secretary for Legislative Affairs BARBARA LARKIN Assistant Secretary for Democracy, Human JOHN SHATTUCK Rights, and Labor Legal Advisor DAVID R. -

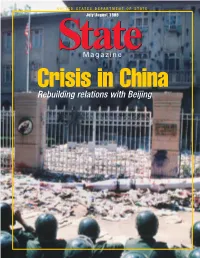

Rebuilding Relations with Beijing Coming in September: Thessaloniki

UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF STATE July/August 1999 StateStateMagazine Crisis in China Rebuilding relations with Beijing Coming in September: Thessaloniki State Magazine (ISSN 1099–4165) is published monthly, except bimonthly in July and August, by the U.S. Department of State, 2201 C St., N.W., Washington, DC. Periodicals postage paid at Washington, State DC. POSTMASTER: Send changes of address to State Magazine, Magazine PER/ER/SMG, SA-6, Room 433, Washington, DC 20522-0602. State Carl Goodman Magazine is published to facilitate communication between manage- ment and employees at home and abroad and to acquaint employees EDITOR-IN-CHIEF with developments that may affect operations or personnel. The Donna Miles magazine is also available to persons interested in working for the DEPUTY EDITOR Department of State and to the general public. Kathleen Goldynia State Magazine is available by subscription through the DESIGNER Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office, Isaias Alba IV Washington, DC 20402 (telephone [202] 512-1850). The magazine can EDITORIAL ASSISTANT be viewed online free at www.state.gov/www/publications/statemag. The magazine welcomes State-related news and features. Informal ADVISORY BOARD MEMBERS articles work best, accompanied by photographs. Staff is unable to James Williams acknowledge every submission or make a commitment as to which CHAIRMAN issue it will appear in. Photographs will be returned upon request. Articles should not exceed five typewritten, double-spaced Sally Light pages. They should also be free of acronyms (with all office names, EXECUTIVE SECRETARY agencies and organizations spelled out). Photos should include Albert Curley typed captions identifying persons from left to right with job titles. -

DEPARTMENT of STATE 2201 C Street NW., Washington, DC 20520 Phone, 202–647–4000

DEPARTMENT OF STATE 2201 C Street NW., Washington, DC 20520 Phone, 202±647±4000. Internet, www.state.gov. SECRETARY OF STATE MADELEINE K. ALBRIGHT Assistant Secretary for Intelligence and J. STAPLETON ROY Research Assistant Secretary for Legislative Affairs BARBARA LARKIN Chairman, Foreign Service Grievance Board EDWARD REIDY Chief of Protocol MARY MEL FRENCH Chief of Staff ELAINE K. SHOCAS Civil Service Ombudsman TED A. BOREK Counselor of the Department of State WENDY SHERMAN Deputy Assistant Secretary for Equal DEIDRE A. DAVIS Employment Opportunity and Civil Rights Director, Policy Planning Staff MORTON H. HALPERIN Inspector General JACQUELYN L. WILLIAMS-BRIDGERS Legal Advisor DAVID R. ANDREWS Special Assistant to the Secretary and KRISTIE A. KENNEY Executive Secretary of the Department Deputy Secretary of State STROBE TALBOTT Under Secretary for Arms Control and JOHN D. HOLUM, Acting International Security Affairs Assistant Secretary for Arms Control AVIS T. BOHLEN Assistant Secretary for Nonproliferation ROBERT J. EINHORN Assistant Secretary for Political-Military ERIC NEWSOM Affairs Assistant Secretary for Verification and (VACANCY) Compliance Under Secretary for Economic, Business, and ALAN P. LARSON Agricultural Affairs Assistant Secretary for Economic and EARL ANTHONY WAYNE Business Affairs Under Secretary for Global Affairs FRANK E. LOY Assistant Secretary for Democracy, Human HAROLD H. KOH Rights, and Labor Assistant Secretary for International RAND BEERS Narcotics and Law Enforcement Affairs Assistant Secretary for Oceans and DAVID B. SANDALOW International Environmental and Scientific Affairs Assistant Secretary for Population, JULIA V. TAFT Refugee, and Migration Affairs Under Secretary for Management BONNIE R. COHEN Assistant Secretary for Administration PATRICK F. KENNEDY Assistant Secretary for Consular Affairs MARY A. -

Teză De Doctorat

UNIVERSITATEA BABEȘ-BOLYAI FACULTATEA DE STUDII EUROPENE TEZĂ DE DOCTORAT Coordonator științific: Candidat: Prof. univ. dr. Valentin Naumescu Ioana-Nelia Bercean CLUJ-NAPOCA 2021 THE GREAT POWERS’ NUCLEAR DIPLOMACY TOWARD IRAN 2003-2015 From the “Grand Bargain” to the JCPOA v DIPLOMAȚIA NUCLEARĂ A MARILOR PUTERI FAȚĂ DE IRAN 2003-2015. De la “Grand Bargain” la JCPOA Rezumat 2 Cuprins Mulțumiri 6 Notă privind traducerea 7 SECȚIUNEA I: INTRODUCERE 8 1. Requiem Nuclear 8 2. Interes de cercetare 10 3. Revizuirea literaturii 18 4. Ansamblul metodologic 21 4. 1. Repere metodologice 21 4. 1. 1. Analiza exploratorie calitativă 23 4. 1. 2. Metoda cantitativă 24 4. 1. 3. Modelul cognitiv 25 4. 1. 4. Abordările lui Oliver Richmond privind gestionarea conflictelor 26 4. 1. 5. Modelul analizei politicii externe a lui James Rosenau 28 4. 1. 6. Analiza de discurs aplicată editorialelor internaționale de elită 30 4. 1. 7. Teoria jocului 101 – Negocierile nucleare dintre P5 + 1 și Iran 31 4. 2. Harta conceptuală 34 4. 2. 1. Concepte 34 4. 2. 2. Definiții 46 5. Cadrul teoretic 48 5. 1. Realism 49 5. 1. 1. Dilema balanței de putere: “De ce Iranul ar trebui să aibă bomba?” 53 5. 1. 2. Agresiunea calculată 55 5. 1. 3. Doctrina președintelui Barack Obama și puterea hegemonică 57 5. 2. Liberalism 59 5. 2. 1. Instituționalism: Negocierea acordurilor în relațiile internaționale 61 5. 2. 2. “Când multilateralismul a întâlnit realismul – și a încercat să încheie un acord iranian” 64 5. 3. Constructivism 65 5. 3. 1. Aspirațiile nucleare ale Iranului - O perspectivă constructivistă 66 5. -

Patrick C. Costello 1

Patrick C. Costello 1 President Biden, on the eve of his 100th day in office, delivered a historic address to a joint session of Congress. The President also convened a climate summit with the world’s leading economies. Divisions within the Republic Party demonstrate former President Trump’s hold on the party. President Biden declared an end to the war in Afghanistan and pledged to withdraw all American troops by September 11, 2021. Relations with Russia are tense and the administration sanctioned Russian entities and individuals for a range of actions. A massive cyberattack forced one of the largest fuel pipelines in the United States to shut down. The results of the decennial census in the United States were released and will realign some state’s power in the Congress. Biden’s address to Congress and the First 100 Days On April 28, President Biden delivered an address to a joint session of Congress to mark his 100th day in office. For the first time in American history, the President addressed the House chamber standing in front of two women, House Speaker Nancy Pelosi and Vice President Kamala Harris. Biden acknowledged the unprecedented challenges facing America—the worst pandemic in a century, the worst economic crisis since the Great Depression, and the worst attack on our democracy since the Civil War—and declared that “America is on the move again, turning peril into possibility, crisis to opportunity, setbacks into strength.” The President used the address to promote the “American Families Plan,” what the President called “human -

Biden White House: Potential Cabinet Nominations and Senior Appointments

Biden White House: Potential Cabinet Nominations and Senior Appointments These are individuals we have either seen reported or are rumored to be in the mix for a cabinet nomination, senior appointment, or other roles in a potential Biden Administration. Please feel free to reach out to us with specific staffing questions. We have long standing ties to Vice President Biden, his campaign staff, members of the transition team, and a great many of the individuals listed in this document. October 21, 2020 Table of Contents • Notes: Slide 3-5 • Potential Cabinet Agency Appointments: Slides 6-70 • Potential Senior White House Appointments: Slides 71-95 • Potential Independent Agency Appointments: Slides 96-112 • Potential Democratic Party Officials: 113-114 • Other Individuals up for Consideration: Slides 115-118 2 Notes • This document compiles all the names we have been hearing for cabinet agencies, independent agencies, senior White House staff, and other potential positions in a Biden Administration. • While our list keeps growing, we have tried to limit the people included under each heading to just those who are likely to be serious contenders for each role, although there are certainly more people who are interested and potentially campaigning for positions. • In some cases, we have specified candidates who might be in the running for the most senior job at an agency, such as a cabinet Secretary position, but acknowledge that some of these individuals might also accept a Deputy Secretary, Undersecretary, or similar role at another agency if someone else is appointed to the top job. Some folks, however, are likely to only be interested in the most senior slot. -

Department of State

DEPARTMENT OF STATE 2201 C Street, NW., 20520, phone (202) 647–4000 JOHN F. KERRY, Secretary of State; born in Denver, CO, December 11, 1943; education: graduated, St. Paul’s School, Concord, NH, 1962; B.A., Yale University, New Haven, CT, 1966; J.D., Boston College Law School, Boston, MA, 1976; served, U.S. Navy, discharged with rank of lieutenant; decorations: Silver Star, Bronze Star with Combat ‘‘V’’, three Purple Hearts, various theatre campaign decorations; attorney, admitted to Massachusetts Bar, 1976; appointed first assistant district attorney, Middlesex County, 1977; elected lieutenant governor, Massachusetts, 1982; married: Teresa Heinz; Senator from Massachusetts, 1985–2013; commit- tees: chair, Foreign Relations; Commerce, Science, and Transportation; Finance; Small Business and Entrepreneurship; appointed to the Democratic Leadership for 104th and 105th Congresses; nominated by President Barack Obama to become the 68th Secretary of State, and was confirmed by the U.S. Senate on January 29, 2013. OFFICE OF THE SECRETARY Secretary of State.—John F. Kerry, room 7226, 647–9572. Deputy Secretary.—Antony J. ‘‘Tony’’ Blinken. Deputy Secretary for Management and Resources.—Heather Anne Higginbottom. Executive Assistant.—Lisa Kenna, 647–8102. Chief of Staff.—Jonathan Finer, 647–5548. AMBASSADOR-AT-LARGE FOR WAR CRIMES ISSUES Ambassador-at-Large.—Stephen J. Rapp, room 7419A, 647–6051. Deputy.—Jane Stromseth, 647–9880. OFFICE OF THE CHIEF OF PROTOCOL Chief of Protocol.—Amb. Peter Selfridge, room 1238, 647–4543. Deputy Chiefs: Natalie Jones, 647–1144; Mark Walsh, 647–4120. OFFICE OF CIVIL RIGHTS Director.—John M. Robinson, room 7428, 647–9295. Deputy Director.—Gregory B. Smith. BUREAU OF COUNTERTERRORISM Coordinator.—Tina Kaidaow (acting), room 2509, 647–9892.