Problems of Tribal Development in Coastal Karnataka

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Study on Life Style of Jenu Kuruba Tribes Working As Unorganised Labourers

Jenu Kuruba Tribes / 79 A Study on Life Style of Jenu Kuruba Tribes working as Unorganised Labourers * Pradeep M D ** Kalicharan M L Abstract Tribals usually are primitive people, living socially as homogeneous unit with their own culture different subsistence pattern, custom, superstitious beliefs, distinct life style living in isolation from outside influence. Forests are closely associated with the tribal economy and culture. Foreign invasion affected tribal life by assimilating through invading their culture. The independent India saw the legal takeover of prime tribal lands in the name of development dispelling millions of tribes. The Government of India adopted a policy to integrate tribes with modernization by encouraging partnership between the tribes and non tribes. The policy of integration or progressive acculturation has laid the foundation for the march of the tribes towards Equality, Upward Mobility, Economic viability and National mainstreaming. The tribes who are very backward are grouped into ‘Primitive Tribes’ having a low level of literacy, declining in population, poor technological access and extreme economic backwardness. Jenu Kuruba Tribes are one of the vulnerable Tribal Groups living in the state of Karnataka. This paper examines the socio-economic life of Jenu Kuruba Tribes covering personal profile, economic condition, literacy, housing pattern and the use of welfare schemes. This research will suggest ways for new interventions to solve the problems through the collective intervention of government officials, local administration, social workers, and the general public. Key Words: Tribes, Culture, Primitive People, Adjustment, Welfare. Introduction The word 'Tribe' is derived from the Latin word 'Tribus' meaning one among the three people, 'Ramayana' denotes 'Jana' the people with different physical appearance, having superstitious beliefs. -

IPPF: India: Rajasthan Renewable Energy Transmission Investment

Indigenous Peoples Planning Framework (IPPF) Document Stage: Draft for Consultation Project Number: June 2012 India: Rajasthan Renewable Energy Transmission Investment Program Rajasthan Rajya Vidyut Prasaran Nigam Limited (RRVPNL) Government of Rajasthan The Indigenous Peoples Planning Framework is a document of the borrower. The views expressed herein do not necessarily represent those of ADB‘s Board of Directors, Management, or staff, and may be preliminary in nature. Page 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS LIST OF ACRONYMS ............................................................................................................. A. INTRODUCTION…………………………………………………………………………….. B. OBJECTIVES AND POLICY FRAMEWORK…………………………………………… C. IDENTIFICATION OF AFFECTED INDIGENOUS PEOPLES ……………………….. D. SOCIAL IMPACT ASSESSMENT AND STEPS FOR FORMULATING AN IPP …... 1. Preliminary Screening………………………………………………….…..…….. 2. Social Impact Assessment………………………………………………..….….. 3. Benefits Sharing and Mitigation Measures………………………..…..………. 4. Indigenous Peoples Plan…………………………………………………..…..…. E. CONSULTATION, PARTICIPATION AND DISCLOSURE …………………….……... F. GRIEVANCE REDRESS MECHANISM…………………………………………….…….. G. INSTITUTIONAL AND IMPLEMENTATION ARRANGEMENTS……………….……… H. MONITORING AND REPORTING ARRANGEMENTS ………………………….……… I. BUDGET AND FINANCING ………………………………………………………….……. ANNEXURE Annexure-1 LEGAL FRAMEWORK …………………………………………………………….. Annexure-2 INDIGENOUS PEOPLES IMPACT SCREENING CHECKLIST………..…….. Annexure-3 OUTLINE OF AN INDIGENOUS PEOPLES PLAN ….………………………… Page 2 List of Acronyms -

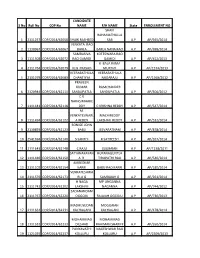

S No Roll No COP No CANDIDATE NAME F/H NAME State

CANDIDATE S No Roll No COP No NAME F/H NAME State ENROLLMENT NO SHAIK RAHAMATHULLA 1 2111257 COP/2014/62058 SHAIK RASHEED SAB A.P AP/945/2014 VENKATA RAO 2 1130967 COP/2014/62067 BARLA BARLA NANA RAO A.P AP/698/2014 SAMBASIVA KOTESWARA RAO 3 1111308 COP/2014/62072 RAO GAMIDI GAMIDI A.P AP/452/2013 K BALA RAMA 4 2111764 COP/2014/62079 KLN PRASAD MURTHY A.P AP/1574/2013 VEERABATHULA VEERABATHULA 5 2131079 COP/2014/62083 CHANTIYYA NAGARAJU A.P AP/1568/2012 PRAVEEN KUMAR RAMCHANDER 6 2120944 COP/2014/62111 SANDUPATLA SANDUPATLA A.P AP/306/2012 C V NARASIMHARE 7 1111441 COP/2014/62118 DDY C KRISHNA REDDY A.P AP/547/2014 M. VENKATESWARL MACHIREDDY 8 1111494 COP/2014/62122 A REDDY LAKSHMI REDDY A.P AP/532/2014 BONIGE JOHN 9 2130893 COP/2014/62123 BABU JEEVARATNAM A.P AP/878/2014 10 2541694 COP/2014/62140 S SANTHI R SATHEESH A.P AP/267/2014 11 2111643 COP/2014/62148 C RAJU SUGRAIAH A.P AP/1238/2011 SATYANARAYAN RUPANAGUNTLA 12 1111480 COP/2014/62150 A R. TIRUPATHI RAO A.P AP/540/2014 AMBEDKAR 13 2131102 COP/2014/62154 KARRI BABU RAO KARRI A.P AP/180/2014 VENKATESHWA 14 2111570 COP/2014/62173 RLU G SAMBAIAH G A.P AP/261/2014 H NAGA MP LINGANNA 15 2111742 COP/2014/62202 LAKSHMI NAGANNA A.P AP/744/2012 SADANANDAM 16 2111767 COP/2014/62220 OGGOJU RAJAIAH OGGOJU A.P AP/736/2013 MADHUSUDAN MOGILAIAH 17 2111661 COP/2014/62231 KACHAGANI KACHAGANI A.P AP/478/2014 MOHAMMAD MOHAMMAD 18 1111532 COP/2014/62233 DILSHAD RAHIMAN SHARIFF A.P AP/550/2014 PUNYAVATHI NAGESHWAR RAO 19 1121035 COP/2014/62237 KOLLURU KOLLURU A.P AP/2309/2013 G SATHAKOTI GEESALA 20 2131021 COP/2014/62257 SRINIVAS NAGABHUSHANAM A.P AP/1734/2011 GANTLA GANTLA SADHU 21 1131067 COP/2014/62258 SANYASI RAO RAO A.P AP/1802/2013 KOLICHALAM NAVEEN KOLICHALAM 22 1111688 COP/2014/62265 KUMAR BRAHMAIAH A.P AP/1908/2010 SRINIVASA RAO SANKARA RAO 23 2131012 COP/2014/62269 KOKKILIGADDA KOKKILIGADDA A.P AP/793/2013 24 2120971 COP/2014/62275 MADHU PILLI MAISAIAH PILLI A.P AP/108/2012 SWARUPARANI 25 2131014 COP/2014/62295 GANJI GANJIABRAHAM A.P AP/137/2014 26 2111507 COP/2014/62298 M RAVI KUMAR M LAXMAIAH A.P AP/177/2012 K. -

Price List of PUBLICATIONS 1939-2014

Price list of PUBLICATIONS 1939-2014 DECCAN COLLEGE POST-GRADUATE AND RESEARCH INSTITUTE (Deemed University) PUNE 411 006 (INDIA) (1) Terms & Conditions of Sale (This cancels our previous trade terms) Terms 1. Actual postal and packing charges to all orders received from outside India. 2. Postal and packing charges to be borne by the person/institution for all the orders upto Rs. 1000/- in India. 3. Free postal and packing charges to the orders above Rs. 1000/- one time. 4. No discount to individual buyers. 5. 20% discount on all the orders upto Rs. 500/-. 6. 25% discount on all the orders which exceeds Rs. 500/-. 7. Except educational and governmental institutions, books will be supplied ONLY on receipt of Advance Payment against Proforma Invoice. Conditions 1. Out-station buyers should remit the amount, either by M.O. or by Demand Draft drawn on any Nationalized Bank at Pune in the name of ‘Deccan College, Pune’. 2. For the convenience of both the supplier and the buyer and for the early delivery of the books, the books are usually supplied by Registered Book Post marked ‘Printed Books’. 3. Only bulk supply is made by roadways. 4. Books are supplied at buyer’s risk and supplier is not responsible for the books damaged, lost, etc., in transit as also for the delay in delivery of the books. 5. Books once sold and dispatched are not accepted back for any reason on exchanged for other parts. 6. Errors and omissions on the part of the supplier are accepted. 7. Books are not supplied by V.P.P. -

Tables on Scheduled Castes and Scheduled Tribes, Part V-A, Vol-V

PRO. 18 (N) (Ordy) --~92f---- CENSUS O}-' INDIA 1961 VOLUME V GUJARAT PART V-A TABLES ON SCHEDULED CASTES AND SCHEDULED TRIBES R. K. TRIVEDI Superintendent of Census Operations, Gujarat PUBLISHED BY THE MANAGER OF PUBLICATIONS, DELHI 1964 PRICE Rs. 6.10 oP. or 14 Sh. 3 d. or $ U. S. 2.20 0 .. z 0", '" o~ Z '" ::::::::::::::::3i=:::::::::=:_------_:°i-'-------------------T~ uJ ~ :2 I I I .,0 ..rtJ . I I I I . ..,N I 0-t,... 0 <I °...'" C/) oZ C/) ?!: o - UJ z 0-t 0", '" '" Printed by Mafatlal Z. Gandhi at Nayan Printing Press, Ahmedabad-} CENSUS OF INDIA 1961 LIST OF PUBLICATIONS CENTRAl- GoVERNMENT PUBLICATIONS Census of India, 1961 Volume V-:Gujatat is being published in the following parts: I-A General Eep8rt 1-·B Report on Vital Statistics and Fertility Survey I~C Subsidiary Tables II-A General Population Tables n-B(l) General Economic Tables (Table B-1 to B-lV-C) II-B(2) General Economic Tables (Table B-V to B-IX) Il-C Cultural and Migration Tables IU Household Economic Tables (Tables B-X to B-XVII) IV-A Report on Housing and Establishments IV-B Housing and Establishment Tables V-A Tables on Scheduled Castes and Scheduled Tribes V-B Ethnographic Notes on Scheduled Castes and Scheduled Tribes (including reprints) VI Village Survey Monographs (25 Monographs) VII-A Seleted Crafts of Gujarat VII-B Fairs and Fest,ivals VIlI-A Administration Report-EnumeratiOn) Not for Sale VllI-B Administration Report-Tabulation IX Atlas Volume X Special Report on Cities STATE GOVERNMENT PUBLICATIONS 17 District Census Handbooks in English 17 District Census Handbooks in Gujarati CO NTF;N'TS Table Pages Note 1- 6 SCT-I PART-A Industrial Classification of Persons at Work and Non·workers by Sex for Scheduled Castes . -

A Curriculum to Prepare Pastors for Tribal Ministry in India

Andrews University Digital Commons @ Andrews University Dissertation Projects DMin Graduate Research 2007 A Curriculum To Prepare Pastors for Tribal Ministry in India Calvin N. Joshua Andrews University Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.andrews.edu/dmin Part of the Practical Theology Commons Recommended Citation Joshua, Calvin N., "A Curriculum To Prepare Pastors for Tribal Ministry in India" (2007). Dissertation Projects DMin. 612. https://digitalcommons.andrews.edu/dmin/612 This Project Report is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate Research at Digital Commons @ Andrews University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertation Projects DMin by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Andrews University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ABSTRACT A CURRICULUM TO PREPARE PASTORS FOR TRIBAL MINISTRY IN INDIA by Calvin N. Joshua Adviser: Bruce L. Bauer ABSTRACT OF GRADUATE STUDENT RESEARCH Dissertation Andrews University Seventh-day Adventist Theological Seminary Title: A CURRICULUM TO PREPARE PASTORS FOR TRIBAL MINISTRY IN INDIA Name of researcher: Calvin N. Joshua Name and degree of faculty adviser: Bruce L. Bauer, DMiss. Date Completed: September 2007 Problem The dissertation project establishes the existence of nearly one hundred million tribal people who are forgotten but continue to live in human isolation from the main stream of Indian society. They have their own culture and history. How can the Adventist Church make a difference in reaching them? There is a need for trained pastors in tribal ministry who are culture sensitive and knowledgeable in missiological perspectives. Method Through historical, cultural, religious, and political analysis, tribal peoples and their challenges are identified. -

The Effect of Development on the Culture of the Adivasis" (2009)

Claremont Colleges Scholarship @ Claremont CMC Senior Theses CMC Student Scholarship 2009 Advancement of the Adivasis: The ffecE t of Development on the Culture of the Adivasis Jantrania Akta Claremont McKenna College Recommended Citation Akta, Jantrania, "Advancement of the Adivasis: The Effect of Development on the Culture of the Adivasis" (2009). CMC Senior Theses. Paper 227. http://scholarship.claremont.edu/cmc_theses/227 This Open Access Senior Thesis is brought to you by Scholarship@Claremont. It has been accepted for inclusion in this collection by an authorized administrator. For more information, please contact [email protected]. CLAREMONT McKENNA COLLEGE ADVANCEMENT OF THE ADIVASIS: THE EFFECT OF DEVELOPMENT ON THE CULTURE OF THE ADIVASIS SUBMITTED TO PROFESSOR WILLIAM ASCHER AND DEAN GREGORY HESS BY AKTA JANTRANIA FOR SENIOR THESIS FALL 2008 / SPRING 2009 ARPIL 27, 2009 Table of Contents List of Figures and Tables....................................................................................... ii Acknowledgements ................................................................................................ iii Chapter 1: Introduction ....................................................................................... 1 Objectives of Study ............................................................................................. 4 Diversity of the Adivasis ..................................................................................... 5 Government Policy Toward the Adivasis .......................................................... -

KARNATAKA DATA HIGHLIGHTS: the SCHEDULED TRIBES Census

KARNATAKA DATA HIGHLIGHTS: THE SCHEDULED TRIBES Census of India 2001 The total population of Karnataka, as per 2001 Census is 52,850,562. Of this, 3,463,986 are Scheduled Tribes (STs). The ST population constitutes 6.6 per cent of the state population and 4.1 per cent of the country’s ST population. Forty-nine STs have been notified in Karnataka by the Scheduled Castes and Scheduled Tribes Order (Amendment) Act, 1976 and by the Act 39 of 1991. This is the second highest number, next to Orissa (64) if compared with the number of STs notified in any other states/UTs of the Country. Five STs namely, Kammara, Kaniyan, Kuruba, Maratha and Marati have been notified with area restriction. Kuruba and Maratha have been notified only in Kodagu district, where as Marati in Dakshina Kannada, Kaniyan in Kollegal taluk of Chamarajanagar and Kammara in Dakshina Kannada and Kollegal taluk of Chamarajanagar districts of Karnataka. 2. Of the STs, two namely, Jenu Kuruba and Koraga are among the Primitive Tribal Groups (PTGs) of India having population of 29,828 and 16,071 respectively in 2001 Census. Jenu Kuruba are mainly distributed in Mysore, Kodagu and Bangalore districts, and Koraga in Dakshina Kannada and Dharward districts. In the present census, a low growth rate of 1.6 per cent and a negative growth rate of 1.5 per cent have been reported for the Jenu Kuruba and Koraga respectively. 3. The growth rate of ST population in the decade 1991-2001 at 80.8 per cent is considerably higher in comparison to the overall 17.5 per cent of state population. -

(Amendment) Act, 1976

~ ~o i'T-(i'T)-n REGISTERED No. D..(D).71 ':imcT~~ •••••• '0 t:1t~~~<1~etkof &india · ~"lttl~ai, ~-. ...- .. ~.'" EXTRAORDINARY ~ II-aq 1 PART ll-Section 1 ~ d )\q,,~t,- .PUBLISHE:Q BY AUTHORITY do 151] itt f~T, m1l<fR, fuaq~ 20, 1976/m'i{ 29, 1898 No. ISI] NEWDELID, MONDAY, SEPTEMBER 20, I976/BHADRA 29, I898 ~ ~ iT '~ ~ ~ ;if ri i' ~ 'r.t; ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ iT rnf ;m ~lj l Separate paging is given to this Part in order that it may be ftled as a separate compilat.on I MINISTRY OF LAW, JUSTICE AND COMPANY AFFAIRS (Legislative Department) New Delhi, the 20th Septembe1', 1976/Bhadra 29, 1898 (Saka) The following Act of Parliament received the assent of the President on the 18th September, 1976,and is hereby published for general informa tion:- THE SCHEDULED CASTES AND SCHEDULED TRIBES ORDERS (AMENDMENT) ACT, 1976 No· 100 OF 1976 [18th September, 1976] An Act to provide for the inclusion in, and the exclusion from, the lists of Scheduled Castes and Scheduled Tribes, of certain castes and tribes, for the re-adjustment of representation of parliamentry and assembly constituencies in so far as such re adjustment is necessiatated by such inclusion of exclusion and for matters connected therewith. BE it enacted by Parliament in the Twenty-seventh Year of the R.epublic of India as follows:- 1. (1) This Act may be called the Scheduled Castes and Scheduled Short title and Tribes Orders (Amendment) Act, 1976. Com (2) It shall come into force on such date as the Central Government mence ment. may, by notification in the Official Gazette, appoint. -

Rescuing the Identity of the Adivasis from Their Invisibility. the Encounter Between Jesuits and the Indigenous Peoples of India

Rescuing the Identity of the Adivasis from their Invisibility. The Encounter between Jesuits and the Indigenous Peoples of India Presented by: Carmina Peñarrocha Giménez Supervised by: Dr. Rosana Peris Pichastor Dr. Daniel Pinazo Calatayud PhD Dissertation Doctoral Programme 14003 Castellón de la Plana, May 2017 Development Cooperation Cover Design. Warli Tree of Life [image online] Available at: https://es.pinterest.com/SANOOSMOM/warli-painting [Accessed 1 January 2017] Rescuing the Identity of the Adivasis from their Invisibility. The Encounter between Jesuits and the Indigenous Peoples of India Doctoral Programme 14003 Thesis Dissertation Development Cooperation Presented by: Carmina Peñarrocha Giménez Supervised by: Dr. Rosa Ana Peris Pichastor Dr. Daniel Pinazo Calatayud ---------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- Department of Developmental, Educational and Social Psychology and Methodology Interuniversity Institute of Local Development (IIDL/UJI) Castellón de la Plana, May 2017 Rescuing the Identity of the Adivasis from their Invisibility. The Encounter between Jesuits and the Indigenous Peoples of India 2 Rescuing the Identity of the Adivasis from their Invisibility. The Encounter between Jesuits and the Indigenous Peoples of India The village spirits of the village, the house spirit of the house, our elders, our foreparents, our ancestors, the path you made, the road you showed, we follow after you, we emulate your example. We invite you, we call upon you. You sit with us, you talk with us. A cup of rice beer, a plate of mixed gruel. You drink with us, you eat with us. (prayer word used by the tribal priests) 3 Rescuing the Identity of the Adivasis from their Invisibility. The Encounter between Jesuits and the Indigenous Peoples of India 4 Rescuing the Identity of the Adivasis from their Invisibility. -

CROCS of CHAROTAR Status, Distribution and Conservation of Mugger Crocodiles in Charotar, Gujarat, India

CROCS OF CHAROTAR Status, Distribution and Conservation of Mugger Crocodiles in Charotar, Gujarat, India THE DULEEP MATTHAI NATURE CONSERVATION TRUST Voluntary Nature Conservancy (VNC) acknowledges the support to this publication given by Ruff ord Small Grant Foundation, Duleep Matthai Nature Conservation Trust and Idea Wild. Published by Voluntary Nature Conservancy 101-Radha Darshan, Behind Union Bank, Vallabh Vidyanagar-388120, Gujarat, India ([email protected]) Designed by Niyati Patel & Anirudh Vasava Credits Report lead: Anirudh Vasava, Dhaval Patel, Raju Vyas Field work: Vishal Mistry, Mehul Patel, Kaushal Patel, Anirudh Vasava Data analysis: Anirudh Vasava, Niyati Patel Report Preparation: Anirudh Vasava Administrative support: Dhaval Patel Cover Photo: Mehul B. Patel Suggested Citation: Vasava A., Patel D., Vyas R., Mis- try V. & Patel M. (2015) Crocs of Charotar: Status, distri- bution and conservation of Mugger crocodiles in Charotar region , Gujarat, India. Voluntary Nature Conservancy, Vallabh Vidyanagar, India. Reproduction and dissemination of material in this pub- lication for educational or any non-commercial purpos- es are authorized without any prior written permission from the publisher provided the source is fully acknowl- edged and appropriate credit given. Reproduction of material in this information product for or other com- mercial purposes is prohibited without written permis- sion of the Publisher. Applications for such permission should be addressed to the Managing Trustee, Voluntary Nature Conservancy or by -

Indian Tribal Ornaments; a Hidden Treasure

IOSR Journal of Environmental Science, Toxicology and Food Technology (IOSR-JESTFT) e-ISSN: 2319-2402,p- ISSN: 2319-2399.Volume 10, Issue 3 Ver. II (Mar. 2016), PP 01-16 www.iosrjournals.org Indian Tribal Ornaments; a Hidden Treasure Dr. Jyoti Dwivedi Department of Environmental Biology A.P.S. University Rewa (M.P.) 486001India Abstract: In early India, people handcrafted jewellery out of natural materials found in abundance all over the country. Seeds, feathers, leaves, berries, fruits, flowers, animal bones, claws and teeth; everything from nature was affectionately gathered and artistically transformed into fine body jewellery. Even today such jewellery is used by the different tribal societies in India. It appears that both men and women of that time wore jewellery made of gold, silver, copper, ivory and precious and semi-precious stones.Jewelry made by India's tribes is attractive in its rustic and earthy way. Using materials available in the local area, it is crafted with the help of primitive tools. The appeal of tribal jewelry lies in its chunky, unrefined appearance. Tribal Jewelry is made by indigenous tribal artisans using local materials to create objects of adornment that contain significant cultural meaning for the wearer. Keywords: Tribal ornaments, Tribal culture, Tribal population , Adornment, Amulets, Practical and Functional uses. I. Introduction Tribal Jewelry is primarily intended to be worn as a form of beautiful adornment also acknowledged as a repository for wealth since antiquity. The tribal people are a heritage to the Indian land. Each tribe has kept its unique style of jewelry intact even now. The original format of jewelry design has been preserved by ethnic tribal.