The Syrian-Israeli Talks: the Final Stage

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

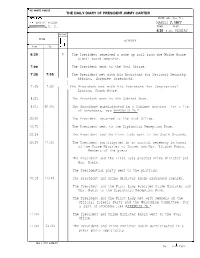

Ihe White House Iashington

HE WHITE HOUSE THE DAILY DIARY OF PRESIDE N T JIMMY CARTER LOCATION DATE (MO., Day, Yr.) IHE WHITE HOUSE MARCH 7, 1977 IASHINGTON, D. C. TIME DAY 6:30 a.m. MONDAY PHONE TIME = 0 E -u ACTIVITY 7 K 2II From To L p! 6:30 R The President received a wake up call from the White House signal board operator. 7:oo The President went to the Oval Office. 7:30 7:35 The President met with his Assistant for National Security Affairs,Zbigniew Brzezinski. 7:45 7:50 I I, The President met with his Assistant for Congressional Liaison, Frank Moore. 8:Ol The President went to the Cabinet Room. 8:Ol 10:05 The President participated in a Cabinet meeting For a list of attendees,see APPENDIX "A." 1O:05 The President returned to the Oval Office. 1O:25 The President went to the Diplomatic Reception Room. 1O:26 The President and the First Lady went to the South Grounds. 1O:26 1l:OO The President participated in an arrival ceremony in honor of the Prime Minister of Israel and Mrs. Yitzhak Rabin. Members of the press The President and the First Lady greeted Prime Minister and Mrs. Rabin. The Presidential party went to the platform. 10:35 10:45 The President and Prime Minister Rabin exchanged remarks. The President and the First Lady escorted Prime Minister and Mrs. Rabin to the Diplomatic Reception Room. The President and the First Lady met with members of the Official Israeli Party and the Welcoming Committee. For a list of attendees ,see APPENDIX& "B." 11:oo The President and Prime Minister Rabin went to the Oval Office. -

The Nobel Peace Prize

TITLE: Learning From Peace Makers OVERVIEW: Students examine The Dalai Lama as a Nobel Laureate and compare / contrast his contributions to the world with the contributions of other Nobel Laureates. SUBJECT AREA / GRADE LEVEL: Civics and Government 7 / 12 STATE CONTENT STANDARDS / BENCHMARKS: -Identify, research, and clarify an event, issue, problem or phenomenon of significance to society. -Gather, use, and evaluate researched information to support analysis and conclusions. OBJECTIVES: The student will demonstrate the ability to... -know and understand The Dalai Lama as an advocate for peace. -research and report the contributions of others who are recognized as advocates for peace, such as those attending the Peace Conference in Portland: Aldolfo Perez Esquivel, Robert Musil, William Schulz, Betty Williams, and Helen Caldicott. -compare and contrast the contributions of several Nobel Laureates with The Dalai Lama. MATERIALS: -Copies of biographical statements of The Dalai Lama. -List of Nobel Peace Prize winners. -Copy of The Dalai Lama's acceptance speech for the Nobel Peace Prize. -Bulletin board for display. PRESENTATION STEPS: 1) Students read one of the brief biographies of The Dalai Lama, including his Five Point Plan for Peace in Tibet, and his acceptance speech for receiving the Nobel Prize for Peace. 2) Follow with a class discussion regarding the biography and / or the text of the acceptance speech. 3) Distribute and examine the list of Nobel Peace Prize winners. 4) Individually, or in cooperative groups, select one of the Nobel Laureates (give special consideration to those coming to the Portland Peace Conference). Research and prepare to report to the class who the person was and why he / she / they won the Nobel Prize. -

Bracing for an Israel-Iran Confrontation in Syria | The

MENU Policy Analysis / Articles & Op-Eds Bracing for an Israel-Iran Confrontation in Syria by Ehud Yaari Apr 30, 2018 Also available in Arabic ABOUT THE AUTHORS Ehud Yaari Ehud Yaari is a Lafer International Fellow at The Washington Institute. Articles & Testimony Despite the recent escalation, the United States has options for preventing, or at least limiting the scope of, a regional showdown in Syria. srael and Iran are on course for a collision in the near future. Indeed, a military clash that could expand well I beyond Syrian territory appears almost inevitable. In particular, Iran’s Islamic Revolutionary Guards Corps (IRGC) is determined to transform Syria into a platform for a future war against Israel, whereas leaders of the Jewish state have sworn to prevent what they often describe as the tightening of a noose around Israel’s neck. The past five years have already seen a series of direct clashes between the two powers. These include more than 120 Israeli Air Force (IAF) strikes against weapons shipments to Hezbollah, Iranian attempts to instigate cross- border incidents along the Golan Heights, and Israeli targeting of arms-production facilities introduced by Iran. In early 2018, these exchanges have escalated to include Israeli airstrikes on Iranian UAV facilities established deep in the Syrian desert, at the T-4 Air Base, and a first Iranian attempt to stage an armed drone attack in Israel. Iran has committed publicly to conducting a forceful retaliation for the Israeli strike in January that killed eight Iranian officers, including UAV unit commander Colonel Mehdi Dehghani. Meanwhile, Israeli Prime Minister Binyamin Netanyahu has threatened vaguely that a confrontation in Syria could prompt Israel to target Iranian territory. -

CAREN WEINBERG, PHD [email protected] • +972 (0)50 527-9553

CAREN WEINBERG, PHD [email protected] • +972 (0)50 527-9553 Dr. Weinberg is recognized in both industry and academia as a fully qualified educator and researcher based on distinguished achievements throughout an extensive executive management career focused on innovation and entrepreneurship in global environments. She developed processes for the creation and introduction of organizational initiatives to maintain and enhance innovation within both start-up and corporate entities. She has designed business and marketing plans to benefit from cultural differences and increase collaborative value for partnerships. Worked with and for the majority of the worlds Fortune 100 Companies, lectures, develops curriculum and takes part in research in major higher educational institutions worldwide. KEY STRENGTHS Continuously promotes innovation and entrepreneurship through participation in both industry and academic forums as a recognized expert in the field. Passion for technology innovation and entrepreneurial education supported by extensive formal education, executive experience as a leader and mentor, continual advancement, and champion in the development of educational and career development initiatives for undergraduates, graduates, entrepreneurs and executives. Long history of introducing and managing academic – industry partnerships that not only provide real- world experience for students but solve actual problems and needs for firms involved. Committed to creation of student-centered learning environments, academic programs, and processes that support the institution’s mission and goals for exceptional academic and personal excellence though creative and innovative teaching methods and industry partnerships. Value collaboration, team work and open communication among all organizational levels. Known for energy, depth of knowledge, integrity, and fairness, combined with strong team leadership to achieve results, and surpass expectations. -

Brown Office of International Programs (OIP) Approved Program List

Brown Office of International Programs (OIP) Approved Program List Country Program Location Program Name Institution Timing Language Argentina Buenos Aires CIEE:IFSA-Butler: Facultad Argentine Latinoamericana Universities de CienciasProgram Sociales & Universidad de Buenos FacultadArgentine Latinoamericana Universities Program de Ciencias Sociales & Universidad Sem/Year Spanish Argentina Buenos Aires Aires de Buenos Aires Sem/Year Spanish Argentina Buenos Aires IES: Advanced Spanish Honors Program Advanced Spanish Honors Program Sem/Year Spanish Argentina Mendoza IFSA-Butler: Universidad Nacional de Cuyo Universidad Nacional de Cuyo Sem/Year Spanish Australia Brisbane Arcadia University: University of Queensland University of Queensland Sem/Year English Australia Brisbane University of Queensland - Direct Enrollment University of Queensland Sem/Year English Australia Brisbane IFSA-Butler: University of Queensland University of Queensland Sem/Year English Australia Cairns SIT: Australia- Rainforest, Reef, and Cultural Ecology SIT Field Station Semester English Australia Canberra Arcadia University: Australian National University Australian National University Sem/Year English Australia Canberra Australian National University - Direct Enrollment Australian National University Sem/Year English Australia Canberra IFSA-Butler: Australian National University Australian National University Sem/Year English Australia Hobart University of Tasmania, Hobart - Direct Enrollment University of Tasmania, Hobart Sem/Year English Australia Hobart IFSA-Butler: -

Yitzhak Rabin

YITZHAK RABIN: CHRONICLE OF AN ASSASSINATION FORETOLD Last year, architect-turned-filmmaker Amos Gitaï directed Rabin, the Last EN Day, an investigation into the assassination, on November 4, 1995, of the / Israeli Prime Minister, after a demonstration for peace and against violence in Tel-Aviv. The assassination cast a cold and brutal light on a dark and terrifying world—a world that made murder possible, as it suddenly became apparent to a traumatised public. For the Cour d’honneur of the Palais des papes, using the memories of Leah Rabin, the Prime Minister’s widow, as a springboard, Amos GitaI has created a “fable” devoid of formality and carried by an exceptional cast. Seven voices brought together to create a recitative, “halfway between lament and lullaby,” to travel back through History and explore the incredible violence with which the nationalist forces fought the peace project, tearing Israel apart. Seven voices caught “like in an echo chamber,” between image-documents and excerpts from classic and contemporary literature— that bank of memory that has always informed the filmmaker’s understanding of the world. For us, who let the events of this historic story travel through our minds, reality appears as a juxtaposition of fragments carved into our collective memory. AMOS GITAI In 1973, when the Yom Kippur War breaks out, Amos Gitai is an architecture student. The helicopter that carries him and his unit of emergency medics is shot down by a missile, an episode he will allude to years later in Kippur (2000). After the war, he starts directing short films for the Israeli public television, which has now gone out of business. -

School Programme

FOURTEENTH CEPR/JIE CONFERENCE ON APPLIED INDUSTRIAL ORGANIZATION Hosted by University of Bologna Supported by University of Bologna Journal of Industrial Economics (JIE) CEPR Bologna; 22-25 May 2013 IO SCHOOL PROGRAMME WEDNESDAY 22 MAY 08.40 – 09.00 Welcoming Remarks Session 1: Chair: Jozsef Molnar (European Commission) 09.00 – 09.50 Pharmaceuticals, Incremental Innovation and Market Exclusivity *Nina Yin (Toulouse School of Economics) Discussant: Jozsef Molnar (European Commission) 09.50 – 10.40 The Effect of Uncertain Evaluations on Procurement Costs: Theory and Evidence from Design/Build Auctions *Hidenori Takahashi (University of Toronto) Discussant: Andrea Pozzi (Einaudi Institute for Economics and Finance) 10.40 – 11.00 Coffee Break Session 2: Chair: John Morrow (London School of Economics) 11.00 – 11.50 Two-sided Markets with Switching Costs and Heterogeneous Consumers *Wing Man Wynne Lam (Università di Bologna) Discussant: Vincenzo Denicolò (Università di Bologna and University of Leicester and CEPR) 11.50 – 12.40 Learning by Doing and Consumer Switching Cost *Yufeng Huang (Tilburg University) Discussant: Emanuele Tarantino (Università di Bologna) 12.40 – 14.10 Lunch 1 Session 3: Chair: Luca Lambertini (Università di Bologna) 14.10 – 15.00 Hotelling Meets Holmes: The Importance of Returns to Product Differentiation and Distribution Economies for the Firm's Optimal Location Choice *Anett Erdmann (Universidad Carlos III de Madrid) Discussant: Luca Lambertini (Università di Bologna) 15.00 – 15.50 Dynamic Discrete Choice Estimation -

19Th EU Contest for Young Scientists

The Jury – Valencia, 14-19 September 2007 The jury is composed of a president and 14 other jury members. They carry out their duties as individuals and not as representatives of an institution or country. The members of the jury are selected on the basis of scientific criteria to represent their discipline. They are drawn from both academia and industry. The Commission appoints the Jury annually. At least one third of the jury members are replaced each year in accordance with normal Commission procedures. President of the Jury Hansen, Vagn Lundsgaard Technical University of Denmark Vagn Lundsgaard Hansen is Professor of Mathematics since 1980 at the Technical University of Denmark and Scientific Director of LearningLab-TUD since 2005. He earned a Masters degree in mathematics and physics from the University of Aarhus, Denmark, 1966, and a PhD in mathematics from the University of Warwick, England, 1972. He has authored numerous research papers in mathematics (geometry, topology, global analysis) and several books. Research interests also include mathematical education and the history of mathematics. He was Chairman Committee for Raising Public Awareness of Mathematics appointed by the European Mathematical Society, 2000-2006. Invited speaker “International Congress of Mathematicians, Beijing 2002” and invited regular lecturer “10th International Congress on Mathematical Education, Copenhagen 2004”. He is President Danish Academy of Natural Sciences since 1984 and Member European Academy of Sciences (Brussels) 2004. He was Member of the Danish Natural Science Research Council, 1992-98, and functioned for four years in this period as vice-chairman. Members of the jury Chaleyat-Maurel, Mireille University Paris V Mireille Chaleyat-Maurel is a former student of the Ecole Normale Supérieure de Paris (1965-1968). -

Adi Ben-Israel

Adi Ben-Israel Management Science & Information Systems Rutgers Business School Room 5184, RBS Building 100 Rockafeller Road, Livingston Campus Piscataway, NJ 08854-8054 E-mail: [email protected] 848-445-3243 u 848-445-6329 Web: http://benisrael.net/Adi.html Wikipedia: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Adi_Ben-Israel Google Scholar: https://scholar.google.com/citations?user=y2CF030AAAAJ&hl=en Education 1955 B.Sc. (Mechanical Engineering), Technion-Israel Institute of Technology 1956 Diploma (Mechanical Engineering), Technion-Israel Institute of Technology 1959 M.Sc. (Operations Research/Statistics), Technion-Israel Institute of Technology 1962 Ph.D. (Engineering Science/Applied Mathematics), Northwestern University Professional experience 1988–present Distinguished Professor of Business, Rutgers University Professor II of Mathematics, Rutgers University 1996 Acting Chairman, Department of Management Science and Information Systems, Rutgers University 1976-1988 H. Fletcher Brown Professor of Mathematics, University of Delaware 1976-1979 Chairman, Operations Research Program, University of Delaware 1970-1975 Professor of Applied Mathematics, Technion-Israel Institute of Technology 1973-1975 Chairman, Department of Applied Mathematics, Technion-Israel Institute of Technology 1969-1970 Professor of Engineering Science and Applied Mathematics, Northwestern University 1966-1968 Associate Professor of Engineering Science, Northwestern University 1965-1966 Associate Professor of Systems Engineering, University of Illinois at Chicago Circle -

Jewish Community Federation of Greater Chattanooga

A PUBLICATION OF THE JEWISH COMMUNITY FEDERATION OF GREATER CHATTANOOGA The SHOFAR Volume 8 Number 4 Kislev - Tevet 5754 December, 1993 Jewish Community Federation of Greater Chattanooga It's official. The Board of Directors ofthe new community organi zation formed by the merger of the Chattanooga Jewish Federation Replaces CJF & JCC and the Jewish Community Center of Chattanooga earlier this year decided on October 28,1993 to adopt "Jewish Community Federation Fed. Appoints New Assistant of Greater Chattanooga" as it's official name. What'sin a name.one may ask. "Jewish" was chosen as the first word Director-Program Director because it is the essence of whatwe are and the practicality of those new The appointment of Marcy Goldstein- to the community being able to easily access the institution through the Pellegrino as Assistant Director-Program Di telephone book. "Community" implies our unity and the sense of rector of the Jewish Community Federation shared ownership of all of the Jews in Chattanooga. "Federation" was announced by Pris Siskin, Federation Presi relates to a central organization united for common purpose. "Of dent. "In her capacity as Assistant Director- Greater Chattanooga" refers to the services provided to Jews not only Program Director, Marcy will assist the Fed in our city, but in our surrounding area, including north Georgia. eration Executive Director in developing and supervising programs to enhance the quality of Jewish life in Chattanooga," Mrs. Siskin con Community Chanukah tinued. Specific responsibilities -

1 Schlaglicht Israel Nr. 8/19 Aktuelles Aus Israelischen Tageszeitungen

Schlaglicht Israel Nr. 8/19 Aktuelles aus israelischen Tageszeitungen 16.-30. April Die Themen dieser Ausgabe 1. Netanyahu nimmt Koalitionsverhandlungen auf .......................................................................................................... 1 2. Trumps Jahrhunderteplan für Frieden im Nahen Osten .............................................................................................. 4 3. Pessach 2019 ................................................................................................................................................................... 6 4. Medienquerschnitt ........................................................................................................................................................... 7 1. Netanyahu nimmt Koalitionsverhandlungen die Finanzhilfen an die Hamas aus Katar, die auf Netanyahu zuließ. Ausgerechnet Avigdor Liberman, der mit seinem Rücktritt als Verteidigungsminister im letzten Jahr Israel`s election results show broad consensus mit für den vorgezogenen Termin der Parlaments- on diplomatic and defense wahlen sorgte, war Benjamin Netanyahus erster (…) beyond the harsh rhetoric, one can discern a Ansprechpartner bei den Koalitionsverhandlungen. broad consensus in Israel for the outgoing Staatspräsident Reuven Rivlin hatte zuvor den am- government’s actual diplomatic and defense tierenden Ministerpräsidenten erneut mit der Regie- policies. Both the Likud and Blue-White parties rungsbildung beauftragt. Netanyahu hatte bei den almost entirely ignored -

Inside the Palestinian Authority: a Situation Report by Ehud Yaari

MENU Policy Analysis / PolicyWatch 130 Inside the Palestinian Authority: A Situation Report by Ehud Yaari Apr 11, 1997 ABOUT THE AUTHORS Ehud Yaari Ehud Yaari is a Lafer International Fellow at The Washington Institute. Brief Analysis ince the beginning of the Oslo process, Israel and the United States have consistently underestimated S Palestinian Authority (PA) Chairman Yasser Arafat. Arafat is a historic figure who deserves respect. In his many years as leader of the Palestinians he has learned to employ a wide range of personas and emotions to achieve his ends: he will whine in front of lesser people, he will play the 'clown,' and he will suffer being scolded by junior Israeli generals, if their positions serve his larger purposes. The image of Arafat as a sad old man waiting for a mini- state to crown his career must be replaced with the reality of a vigorous politician who will not even discuss his succession. Arafat said that the Oslo accords can be a repeat of the 1969 Cairo agreement between him and General Boustany, the chief of staff of the Lebanese Army, which allowed Arafat to maintain a small number of guerrillas on the slopes of Mt. Hermon. Arafat used this crack to pry the doors of Lebanon open, and by the late 1980s, the PLO presence in Lebanon was so great that Arafat considered himself-in his own words—"governor-general of Lebanon." Arafat views Oslo as another crack: a corridor through which he can incrementally obtain his strategic goal. The Oslo agreement also served to revive the Palestinian Liberation Organization (PLO).