The Eye of the Needle

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Tricontinental: Institute for Social Research International, Movement-Driven Institution Focused on Stimulating Intellectual Debate That Serves People’S Aspirations

1 Tricontinental: Institute for Social Research international, movement-driven institution focused on stimulating intellectual debate that serves people’s aspirations. The Ninth Newsletter (2018): Tender and Radiant World of Sadness and Struggle celina · Friday, April 27th, 2018 Dear Friends, Sadness and struggle is the mood in Yemen. My Yemeni friends, caught in the midst of an endless war, had a particularly terrible ten days. Saudi-UAE aircraft struck another wedding, while they assassinated an important Yemeni political leader. The UN attempts to raise funds to tend to the 22 million Yemenis who cannot survive without humanitarian assistance. Meanwhile, the new UN Special Envoy leaves his post in Syria – another unforgiving war – to try his hand at a political settlement in Yemen. This is the forgotten war, this war on Yemen – with Western arms dealers making a great deal of money selling munitions to the Saudis and the Emiratis who bomb without care for strategy. The details from this paragraph are in my report at Alternet, which you can read here. Surrender is not familiar to the human spirit. Yemen’s people continue to struggle to Tricontinental: Institute for Social Research - 1 / 6 - 05.08.2021 2 survive. The picture above is of a wall painting done last year by the Yemeni artist Haifa Subay (whom you can follow on twitter: @haifasubay). The horrors of the war in Yemen and Syria appear to be without end. A glance eastward will bring us to the Korean peninsula, where the two leaders of the North (Kim Jong-un) and South (Moon Jae-in) will meet on Friday. -

Living Learning Booklet

Living Learning by Lindela Figlan, Rev. Mavuso, Busi Ngema, Zodwa Nsibande, Sihle Sibisi and Sbu Zikode with guest piece by Nigel Gibson, Anne Harley and Richard Pithouse Rural Network The Church Land Programme (CLP) supports the Living Learning process and published this booklet during 2009. David Ntseng ([email protected]) coordinates the Living Learning programme within CLP, and Mark Butler facilitated the sessions, took the notes and put the booklet together. CLP is based in Pietermaritzburg, KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa. They can be contacted by phone at +27 33 2644380, and their website address is: www.churchland.co.za, where you can download a PDF version of this booklet. Please feel free to make use of the content of this booklet, with appropriate acknowledgement of the organisation and authors. LLivingiving LLearningearning TThehe CContributorsontributors Lindela Figlan Rev. Mavuso is Busi Ngema is is a second year a second year a second year student in the student in the CEPD student in the CEPD CEPD programme. programme. He is programme. She is He is the Vice- the Secretary of the the Youth Organiser President of Abahlali Rural Network. for the Rural BaseMjondolo Network. Movement. Zodwa Nsibande Sihle Sibisi is Sbusiso Zikode has has graduated in the a second year graduated in the CEPD programme. student in the CEPD CEPD programme. She is the National programme. He is the He is the President Secretary of Abahlali Treasurer of Abahlali of Abahlali BaseMjondolo BaseMjondolo BaseMjondolo Maovement. Movement. Movement. TThehe CContributorsontributors 1 TThehe gguestuest ccontributors:ontributors: Nigel C. Gibson is the author Fanon: The Postcolonial Imagination, and the editor of a number of books including Rethinking Fanon; Contested Ter- rains and Constructed Categories: Contemporary Africa in Focus (with George C. -

Vocational Education and Training for Sustainability in South Africa: the Role of Public and Private Provision

International Journal of Educational Development 29 (2009) 149–156 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect International Journal of Educational Development journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/ijedudev Vocational education and training for sustainability in South Africa: The role of public and private provision Simon McGrath a,*, Salim Akoojee b,1 a UNESCO Centre for Comparative Education Research, School of Education, University of Nottingham, Jubilee Campus, Wollaton Road, Nottingham NG8 1BB, United Kingdom b Manufacturing, Engineering and Related Services Sector Education and Training Authority, 3rd Floor Block B, Metropolitan Park, 8 Hillside Road, Parktown 2001, South Africa ARTICLE INFO ABSTRACT Keywords: Written in the twilight of the Mbeki Presidency, this paper considers the role that skills development has South Africa in the sustainability of the South African political–economic project. It explores some of the Private disarticulations of public policy and argues that these both undermine public sector delivery and Public open up opportunities for private provision to be, under certain circumstances, more responsive to the Vocational education and training challenges of national development. We argue that there is a possibility that the state could work more Economic development smartly with both sets of providers. Crucially, however, this would necessitate working more smartly within itself. This was a major plank of the Mbeki strategy but it has failed conspicuously with regard to the Education–Labour relationship. Whether a new President can achieve a radical reworking of this relationship may be an important indicator of the viability of any new development project. The article concludes with reflections on the renewed international interest in skills development as a way of responding to the real and imagined pressures and opportunities of globalisation. -

Anna Selmeczi Central European University Selmeczi [email protected]

“We are the people who don’t count” – Contesting biopolitical abandonment Anna Selmeczi Central European University [email protected] Paper to be presented at the 2010 ISA Convention in New Orleans, February 17-20th Panel: Governing Life Globally: The Biopolitics of Development and Security Work in progress – please do not cite without the author’s permission. Comments are most welcome. 2 “We are the people who don’t count” – Contesting biopolitical abandonment 1. Introduction About a year before his lecture series “Society Must be Defended!”, in which he first elaborated the notion of biopolitics, in a talk given in Rio de Janeiro, Foucault discussed the “Birth of the Social Medicine”. As a half-way stage of the evolution of what later became public health, between the German ‘state medicine’ and the English ‘labor-force medicine’, he described a model taking shape in the 18th century French cities and referred to it as ‘urban medicine’. With view to the crucial role of circulation in creating a healthy milieu, the main aim of this model was to secure the purity of that which circulates, thus, potential sources of epidemics or endemics had to be placed outside the flaw of air and water nurturing urban life. According to Foucault (2000a), it was at this period that “piling-up refuse” was problematized as hazardous and thus places producing or containing refuse – cemeteries, ossuaries, and slaughterhouses – were relocated to the outskirts of the towns. As opposed to this model, which was the “medicine of things”, with industrialization radically increasing their presence in the cities, during the subsequent period of the labor force medicine, workers and the poor had become to be regarded as threats and, in parallel, circulation had been redefined as – beyond the flow of things such as air and water – including the circulation of individuals too (Ibid., 150). -

You'll Never Silence the Voice of the Voiceless

YOU’LL NEVER SILENCE THE VOICE OF THE VOICELESS CRITICAL VOICES OF ACTIVISTS IN POST-APARTHEID SOUTH AFRICA Kate Gunby Richard Pithouse School for International Training South Africa: Reconciliation and Development Fall 2007 Table of Contents Abstract………………………………………………………………………………………..2 Introduction……………………………………………………………………………………3 Background……………………………………………………………………………………4 Abahlali………………………………………………………………………………..4 Church Land Programme…..…………………………………………………….........6 Treatment Action Campaign..…………………………………………………….…...7 Methodology…………………………………..……………………………………………..11 Research Limitations.………………………………………………………………...............12 Interview Write-Ups Harriet Bolton…………………….…………………………………………………..13 System Cele…………………………………………………………………………..20 Lindelani (Mashumi) Figlan...………………………………………………………..23 Gary Govindsamy……………………………………………………………….........31 Louisa Motha…………………………………………………………………………39 Kiru Naidoo…………………………………………………………………………..42 David Ntseng…………………………………………………………………………51 Xolani Tsalong……………………………………………………………….............60 Reflection and Discussion...……………………………………………………………….....66 Teach the Masses that Everything Depends on Them…………………………….....66 The ANC Will Stay in Power for a Long Time……………………….......................67 We Want to be Treated as Decent Human Beings like Everyone Else………………69 Just a Piece of Paper Thrown Aside……………………….........................................69 The Tradition of Obedience……………………………………………………….....70 The ANC Has Effectively Demobilized and Decimated Civil Society……………...72 Don’t Talk About Us, Talk To -

Contact, Vol. 1, No. 12

Contact, Vol. 1, No. 12 Use of the Aluka digital library is subject to Aluka’s Terms and Conditions, available at http://www.aluka.org/page/about/termsConditions.jsp. By using Aluka, you agree that you have read and will abide by the Terms and Conditions. Among other things, the Terms and Conditions provide that the content in the Aluka digital library is only for personal, non-commercial use by authorized users of Aluka in connection with research, scholarship, and education. The content in the Aluka digital library is subject to copyright, with the exception of certain governmental works and very old materials that may be in the public domain under applicable law. Permission must be sought from Aluka and/or the applicable copyright holder in connection with any duplication or distribution of these materials where required by applicable law. Aluka is a not-for-profit initiative dedicated to creating and preserving a digital archive of materials about and from the developing world. For more information about Aluka, please see http://www.aluka.org/. Page 1 of 30 Alternative title ContactContact: The S.A. news review Author/Creator Selemela Publications (Cape Town) Publisher Selemela Publications (Cape Town) Date 1958-07-12 Resource type Journals (Periodicals) Language Afrikaans, English Subject Coverage (spatial) South Africa Coverage (temporal) 1958 Source Digital Imaging South Africa (DISA) Format extent 16 page(s) (length/size) Page 2 of 30 Registered at G.P.O. as a Newspaper12th July, 1958Vol. I No 12INDIAN ZONING `A BLOT ONWorse than Nazicrimes ProfessorTHE plan for zoning Pretoria racially underthe Group Areas Act "would be a blot on the Christian character of South Africa. -

Intellectual Practices of a Poor People's Movement in Post

Interface: a journal for and about social movements Article Volume 6 (1): 185 – 210 (May 2014) Robertson, Professors of our own poverty Professors of our own poverty: intellectual practices of a poor people’s movement in post-apartheid South Africa Cerianne Robertson Abstract This paper addresses how a poor people’s movement contests dominant portrayals of ‘the poor’ as a violent mass in contemporary South African public discourse. To explore how Abahlali baseMjondolo, a leading poor people’s movement, articulates its own representation of ‘the poor,’ I examine two primary intellectual and pedagogical practices identified by movement members: first, discussion sessions in which members reflect on their experiences of mobilizing as Abahlali, and second, the website through which the movement archives a library of its own homegrown knowledge. I argue that these intellectual practices open new spaces for the poor to represent themselves to movement members and to publics beyond shack settlements. Through these spaces, Abahlali demonstrates and asserts the intelligence which exists in the shack settlements, and demands that its publics rethink dominant portrayals of ‘the poor.’ Keywords: Abahlali baseMjondolo, the poor, movement, intellectual and pedagogical practices, South Africa, post-apartheid Introduction On August 16, 2012, at a Lonmin platinum mine in Marikana, South Africa, 34 miners on strike were shot dead by police. South African and global press quickly dubbed the event, “The Marikana Massacre,” printing headlines such as “Killing Field”, “Mine Slaughter”, and “Bloodbath,” while videos of police shooting miners went viral and photographs showed bodies strewn on the ground (Herzkovitz, 2012). In September, South Africa’s Mail & Guardian reported that more striking miners “threw stones at officers” while “plumes of black smoke poured into the sky from burning tyres which workers used as barricades” ("Marikana," 2012). -

Integrating Stats4soccer with Maths4stats in Mpumalanga

THE INSIDE STATS SA: CLICK HERE TO PREVIOUS ACCESS THE ISSUES OF THE PULSE ARCHIVE Pulse 26/04/2019 PULSE OF THE ORGANISATION Integrating Stats4Soccer with Maths4Stats in Mpumalanga The Stats4Soccer team from head office, led by Johnny He further said that Mathematics is not only a classroom Masegela, visited Statistics South Africa’s (Stats SA’s) activity, it is also something practical that one can Mpumalanga office on 10 and 11 April 2019. This was measure, count and analyse. The teachers are so focused the first visit since the 2013 Africa Cup of Nations where on classroom activities that they tend to forget that other Stats4Soccer hosted the Nigerian national team in subjects are practical and learners need to go outside and Nelspruit. experience them. Two schools were identified and visited. Lihawu Secondary The Statistical Support and Informatics (SSI) Director, Mr School in Pienaar was the first school to be visited on Oscar Ndou, referred to the 4th Industrial Revolution that 10 April 2019. The second school visited was Joseph the President, Mr Cyril Ramaphosa, is encouraging and Mathebula Secondary School in Driekoppies on 11 April promoting, as it is very important for Stats SA to play a role 2019. Joseph Mathebula Secondary School was attended in promoting statistics among learners. Learners should by a former Stats SA employee, the late Dr Alfred Ngwane. be encouraged to understand the space where they live so that they can also participate and assist their communities This provincial visit by the Stats4Soccer team is part of to make informed decisions. empowering and building capacity in the Mpumalanga province. -

Unfreedom Day.Pmd

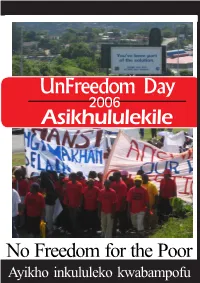

UnFreedom Day 2006 Asikhululekile No Freedom for the Poor Ayikho inkululeko kwabampofu Contents Our Future in South Africa – Letters from Chatsworth............................................................ 4 Ama street traders ePinetown ............................................................................................... 5 “Born After Freedom” – Letters from Foreman Road ............................................................. 6 “Hear our Cries! - Voices from Kennedy Road” .................................................................... 8 He kept me waiting for the house – Joe Slovo Settlement... ................................................... 11 When will the voice of the poors be heard? Lacey Road Settlement ........................................ 11 The City Will Go on in Flames like Khutsong - Umlazi J section .............................................. 11 Izikhalo baseJadhu Place .................................................................................................... 12 We Cannot Allow Our Comrades to be Relocated - Clare Estate Taxi Association .................... 12 Kwa Ward 15 .................................................................................................................. 14 UnFree in Rural Areas ....................................................................................................... 14 South Durban Environmental Action Coalition Demands! ...................................................... 15 God’s City is not Free - Banana City ................................................................................... -

Yousuf Al-Bulushi

THE STRUGGLE FOR A SECOND TRANSITION IN SOUTH AFRICA: UPRISING, DEVELOPMENT AND PRECARITY IN THE POST-APARTHEID CITY Yousuf Al-Bulushi A dissertation submitted to the faculty of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of Geography. Chapel Hill 2014 Approved by: John Pickles Altha Cravey Michael Hardt Scott Kirsch Eunice Sahle ©2014 Yousuf Al-Bulushi ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ii ABSTRACT Yousuf Al-Bulushi: The Struggle for a Second Transition in South Africa: Uprising, Development and Precarity in the Post-Apartheid City (Under the direction of John Pickles) This dissertation explores the limitations of post-apartheid liberation in the specific environment of Durban, South Africa. It takes a social movement of shack dwellers, Abahlali baseMjondolo, as a looking glass into urban debates concerned with the wellbeing of some of South Africa’s most marginalized communities. As the country struggles to deal with the ongoing crises of mass poverty, inequality, and unemployment, the government has responded with a range of developmental projects. At the same time, poor people around the country have protested injustice in record numbers, rivaling levels of unrest in any other part of the world. A mix of state repression and increased governmental redistribution of wealth has been the official response. This study explores these contentious issues by placing them in the context of South Africa’s Second Transition. More broadly, the approach situates the study at multiple geographical scales of analysis from the global to the continental, and the regional to the city. -

Unfreedomnfreedom Dayday Nnewsews Fromfrom Abahlaliabahlali Basemjondolobasemjondolo Movementmovement

EDITION 4: MAY 2008 UUNFreedomNFreedom DayDay NNewsews ffromrom AAbahlalibahlali BBaseMjondoloaseMjondolo MMovementovement KZN Abahlali: SStoriestories ffromrom tthehe ggroundround t is really important to discuss the bigger idea of freedom. It is not enough to taste a little of it ourselves in a small group discussion but always to share with more people, more ears. Our view as Abahlali baseMjondolo is that it is discussed in Ievery settlement to hear what people think and say about ‘Free- dom Day’, to listen to their thinking about Freedom Day and the realities of shack fi res, the Slum Act and so on. We need an open debate about notions of freedom, especially when so much of the people’s lives is a contradiction to freedom. We need to make sure that as a Movement, we remain on the same page as the people’s thinking and understanding. It might be a taste of freedom in itself to do this. So this space of discussing and listen- ing is a small but important part of freedom – the freedom that comes from searching for the truth. Our country is caught in a politics that often prevents us to search for real truth. We don’t say that we in the movements are perfect, but at least we are try- ing, we are opening these gates; at least we are on a right path to search for the truth. We have a deep responsibility to make sure that no-one can shut these gates. When we have unFreedom Day as well as a new law like the Slums Act being pushed at the people by the same politicians, and all in the name and language of ‘freedom’, we see the contra- dictions in our country. -

Issue 1/2 Civil Society.Indd

Interface A journal for and about social movements VOL 1 ISSUE 2: ‘CIVIL SOCIETY’ VS SOCIAL MOVEMENTS Interface: a journal for and about social movements Contents list Volume 1 (2): i – v (November 2009) Interface issue 2: civil society vs social movements Interface: a journal for and about social movements Volume 1 number 2 (November 2009) ISSN 2009 – 2431 Table of contents (i – v) Editorial Ana Margarida Esteves, Sara Motta, Laurence Cox, Civil society versus social movements (pp. 1 – 21) Activist interview Richard Pithouse, To resist all degradations and divisions: an interview with S'bu Zikode (pp. 22 – 47) Articles Nora McKeon, Who speaks for peasants? Civil society, social movements and the global governance of food and agriculture (pp. 48 – 82) Michael Punch, Contested urban environments: perspectives on the place and meaning of community action in central Dublin, Ireland (pp. 83 – 107) i Interface: a journal for and about social movements Contents list Volume 1 (2): i – v (November 2009) Beppe de Sario, "Lo sai che non si esce vivi dagli anni ottanta?" Esperienze attiviste tra movimento e associazionismo di base nell'Italia post-77 (pp. 108 - 133) ("You do realise that nobody will get out of the eighties alive?" Activist experiences between social movement and grassroots voluntary work in Italy after 1977) Marco Prado, Federico Machado, Andrea Carmona, A luta pela formalização e tradução da igualdade nas fronteiras indefinidas do estado contemporâneo: radicalização e / ou neutralização do conflito democrático? (The struggle to formalise and translate equality within the undefined boundaries of the contemporary state: radicalization or neutralization of democratic conflict?) (pp.