Flint Hills History and Folklife by Dr

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Osage Hills State Park Resource Management Plan 2012 [Updated Feb

Osage Hills State Park Resource Management Plan 2012 [updated Feb. 2014] Osage County, Oklahoma Lowell Caneday, Ph.D. With Kaowen (Grace) Chang, Ph.D.; Debra Jordan, Re.D.; Tatiana Chalkidou, Ph.D.; Michael J. Bradley, Ph.D. This page intentionally left blank. 2 Acknowledgements The authors acknowledge the assistance of numerous individuals in the preparation of this Resource Management Plan. On behalf of the Oklahoma Tourism and Recreation Department’s Division of State Parks, staff members were extremely helpful in providing access to information and in sharing of their time. The essential staff providing assistance for the development of the RMP included Michael Vaught, manager of Osage Hills State Park at the initiation of the project; Nick Connor, ranger; Kyle Thoreson, ranger; and Greg Snider, Regional Manager of the Northeast Region, with assistance from other members of the staff throughout Osage Hills State Park. As the RMP process progressed, Nick Connor was named as the manager of Osage Hills State Park. Assistance was also provided by Deby Snodgrass, Kris Marek, and Doug Hawthorne – all from the Oklahoma City office of the Oklahoma Tourism and Recreation Department. Greg Snider, northeast regional manager for Oklahoma State Parks, also assisted throughout the project. It is the purpose of the Resource Management Plan to be a living document to assist with decisions related to the resources within the park and the management of those resources. The authors’ desire is to assist decision-makers in providing high quality outdoor recreation experiences and resources for current visitors, while protecting the experiences and the resources for future generations. -

Oklahoma Territory Inventory

Shirley Papers 180 Research Materials, General Reference, Oklahoma Territory Inventory Box Folder Folder Title Research Materials General Reference Oklahoma Territory 251 1 West of Hell’s Fringe 2 Oklahoma 3 Foreword 4 Bugles and Carbines 5 The Crack of a Gun – A Great State is Born 6-8 Crack of a Gun 252 1-2 Crack of a Gun 3 Provisional Government, Guthrie 4 Hell’s Fringe 5 “Sooners” and “Soonerism” – A Bloody Land 6 US Marshals in Oklahoma (1889-1892) 7 Deputies under Colonel William C. Jones and Richard L. walker, US marshals for judicial district of Kansas at Wichita (1889-1890) 8 Payne, Ransom (deputy marshal) 9 Federal marshal activity (Lurty Administration: May 1890 – August 1890) 10 Grimes, William C. (US Marshal, OT – August 1890-May 1893) 11 Federal marshal activity (Grimes Administration: August 1890 – May 1893) 253 1 Cleaver, Harvey Milton (deputy US marshal) 2 Thornton, George E. (deputy US marshal) 3 Speed, Horace (US attorney, Oklahoma Territory) 4 Green, Judge Edward B. 5 Administration of Governor George W. Steele (1890-1891) 6 Martin, Robert (first secretary of OT) 7 Administration of Governor Abraham J. Seay (1892-1893) 8 Burford, Judge John H. 9 Oklahoma Territorial Militia (organized in 1890) 10 Judicial history of Oklahoma Territory (1890-1907) 11 Politics in Oklahoma Territory (1890-1907) 12 Guthrie 13 Logan County, Oklahoma Territory 254 1 Logan County criminal cases 2 Dyer, Colonel D.B. (first mayor of Guthrie) 3 Settlement of Guthrie and provisional government 1889 4 Land and lot contests 5 City government (after -

Description of Landscape Features, Summary of Existing Hydrologic Data, and Identification of Data Gaps for the Osage Nation, Northeastern Oklahoma, 1890–2012

PreparedPrepared inin cooperationcooperation withwith thethe OsageOsage NationNation DescriptionDescription ofof LandscapeLandscape Features,Features, SummarySummary ofof ExistingExisting HydrologicHydrologic Data,Data, andand IdentificationIdentification ofof DataData GapsGaps forfor thethe OsageOsage Nation,Nation, NortheasternNortheastern Oklahoma,Oklahoma, 1890–20121890–2012 ScientificScientific InvestigationsInvestigations ReportReport 2014–51342014–5134 U.S.U.S. DepartmentDepartment ofof thethe InteriorInterior U.S.U.S. GeologicalGeological SurveySurvey Front cover: Background, Sand Creek in Osage Hills State Park, Oklahoma, 2013; photograph by Stan Paxton. Top, Unnamed tributary of the Arkansas River near Cleveland, Okla., 2013; photograph by Stan Paxton. Bottom, Bird Creek near Pawhuska, Okla., 2013; photograph by Stan Paxton. Back cover: Left, Arkansas River near Cleveland, Okla., 2013; photograph by Stan Paxton. Right, Arkansas River near Ralston, Okla., 2013; photograph by Stan Paxton. Bottom, U.S. Geological Survey drilling rig near Hominy, Okla., 2013; photograph by Stan Paxton. Description of Landscape Features, Summary of Existing Hydrologic Data, and Identification of Data Gaps for the Osage Nation, Northeastern Oklahoma, 1890–2012 By William J. Andrews and S. Jerrod Smith Prepared in cooperation with the Osage Nation Scientific Investigations Report 2014–5134 U.S. Department of the Interior U.S. Geological Survey U.S. Department of the Interior SALLY JEWELL, Secretary U.S. Geological Survey Suzette M. Kimball, Acting Director -

EXPERIENCE the Flint Hills

EXPERIENCE The Flint Hills During the late spring and continuing through mid to late summer, these grasses, whose roots can extend Like No Other Place fifteen feet into the ground, take energy from the sun and transform it into protein in the leaves. Not By Jim Hoy © On Earth only that, but limestone is a soluble rock and those long roots growing down around that stone carry the © BY JIM HOY mineral to their leaves in the form of calcium. Steers eginning near the Nebraska border in Marshall grazing on Flint Hills bluestem are thus taking in both Band Washington Counties, the Flint Hills of protein and calcium. Kansas extend South into Oklahoma, where they Long before white settlers arrived in Kansas Territory are called the Osage Hills. Not only is this area, in 1854, the native peoples here, and throughout sometimes, referred to as the Bluestem Grazing the Great Plains, had burned the prairie. One of the Region, renowned throughout cattle country for its reasons for this aboriginal burning was the same as ability to pack pounds on stocker cattle, it is also the the reason today’s ranchers burn: bison were attracted last remnant of a tallgrass prairie that once ranged to the fresh green grass of a newly burned prairie just from Canada to Texas, from western Ohio to central as cattle are. Kansas. Only about five percent of the original 100,000,000 acres of this prairie survives, and almost Artists and photographers have discovered the beauty all of that is in the Flint Hills. of the Flint Hills. -

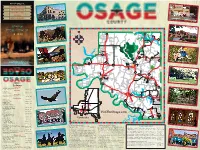

Osage County 2020.Indd

y r e l l a G s i l l u T ' a h C - m u e s u M e s a e r c l i G 1. The Pioneer Woman Mercantile n e d r a G c i n a t o B a s l u T - k o o t a i k S e k a L K Shop and dine at the Pioneer Woman Mercantile in Pawhuska. 532 Kihekah Avenue (918) 528-7705 c o r a l o o W - e l i t n a c r e M n a m o W r e e n o i P e h T E 2. Tallgrass Prairie Preserve The largest tract of remaining tallgrass prairie in the world. The Y headquarters of the Chapman-Barnard Ranch has been converted CR 3225 into a visitor center with restrooms, a gift shop and the restored 12 bunkhouse. The main building is listed in the National Register of Grainola Historic Places (NR 01000208). The gift shop is open from 10 a.m. T to 4 p.m. from March to mid-November. Home to 2,500 free-rang- Hulah Lake ing American Bison! Hulah CR (918)3575 532-4334 O North of Pawhuska, Oklahoma Wildlife Refuge 15316 County Road 4201 (918) 287-4803 3. Osage Hills State Park Foraker Located just west of Bartlesville on U.S. 60 in the heart of the CR 4600 CR 4650 M Kaw Osage Nation in northeast Oklahoma. The park is prime example Wildlife Osage of Oklahoma’s natural beauty. -

Land of the Tallgrass Prairie by John Madson

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Great Plains Quarterly Great Plains Studies, Center for 1995 Review of Where the Sky Began: Land of the Tallgrass Prairie By John Madson Mikko Saikku University of Helsinki Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/greatplainsquarterly Part of the Other International and Area Studies Commons Saikku, Mikko, "Review of Where the Sky Began: Land of the Tallgrass Prairie By John Madson" (1995). Great Plains Quarterly. 1002. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/greatplainsquarterly/1002 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Great Plains Studies, Center for at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Great Plains Quarterly by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. 276 GREAT PLAINS QUARTERLY, FALL 1995 to modern farmers. Their awe before the vast inland sea of grass, their hardships in conquer ing it for agriculture, and their sense of loss once the deed was done receive a fine and highly personal portrayal in Madson's work, though a non-native to the Plains may occa sionally find his narrative slightly sweet. Closely following the recent advances in protection and restoration of the tallgrass prairie, the final chapter has been signifi cantly expanded in the updated edition. In "People's Pastures," Madson lovingly describes the efforts required to restore a patch of old farmland to its original condition. Anyone harboring dreams of a backyard miniprairie will find his accounts encouraging. Madson, an Iowa native, could still have paid more attention to significant on-going restoration and research efforts in Nebraska, Kansas, and Oklahoma. -

Species Diversity of Small Mammals in the Tallgrass Prairie Preserve, Osage County, Oklahoma

51 Species Diversity of Small Mammals in the Tallgrass Prairie Preserve, Osage County, Oklahoma Toni Payne and William Caire Biology Department, University of Central Oklahoma, Edmond, OK 73034 A total of 714 small mammals representing 15 species was captured, identified and released (11,000 trap nights at 110 different trap sites in six different habitat types) at the Tallgrass Prairie Preserve, Osage Co., Oklahoma. More species of small mammals were trapped in the prairie-grass habitat (13 species) than in disturbed areas (9 species), grassy streamsides (7 species), wooded streamsides (6 species), rock outcrops (6 species), or upland woods (6 species) habitats. Species diversity and evenness indices (Shannon's Index) of small mammals were determined for six habitat types. Mean species diversity values ranged from a high value in the prairie-grass habitat, to low values in the upland woods and wooded streamsides habitats. High community similarity (Horn's Index) was found in upland woods and wooded streamsides habitats. Community similarity also was high among prairie-grass, rock outcrops, grassy streamsides, and disturbed habitats. © 1999Oklahoma Academy of Science INTRODUCTION The tallgrass prairie once extended north and south from southern Manitoba to mid-Texas and was the eastern edge of North American grasslands (1). It is bordered on the east by deciduous forest and on the west by mixed-grass prairie. Of all grassland associations, tallgrass prairie receives the most rainfall and has the greatest north-south diversity (1). The tallgrass prairie was a natural system controlled by climate, fire, and bison. The extent of tallgrass prairie has declined with disappearance of bison (Bison bison) and the increase in fire prevention practices. -

Oklahoma Tallgrass Prairie Preserve

OKLAHOMA TALLGRASS PRAIRIE PRESERVE PROJECT AREA DESCRIPTION PROJECT DESCRIPTION In presettlement times, the tallgrass prairie As early as the 1930s, the National Park spanned 142 million acres from Canada to Service recognized that tallgrass prairies the Gulf of Mexico. It evolved under the were not protected in a large enough area forces of weather, bison grazing, and fire. to recreate a functioning tallgrass Starting with European settlement, over ecosystem. Since the only sizable tracts 90% of the tallgrass prairie has been of tallgrass prairie could be found in the Location: converted to agriculture. Flint and Osage Hills of Kansas and Northeastern Oklahoma, subsequent efforts by the Na- Oklahoma The Oklahoma Tallgrass Prairie Preserve is tional Park Service and conservation located in the Osage Hills. The rolling organizations focused on these states. hills are covered by tallgrass prairie These efforts collapsed with the failure of interspersed with streams and post oak- a bill proposing a Tallgrass National Project size: blackjack oak savannas. The Preserve Preserve in Osage County, Oklahoma. 37,000 acres encompasses most of the upper portion of the Sand Creek watershed, and is buffered In consultation with an interdisciplinary by adjacent privately-owned cattle team of experts, The Nature Conservancy ranches. Some 500 to 700 plant species (TNC) realized that a tallgrass preserve Initiator: can be found in the Preserve. area should encompass a watershed, and The Nature should be large enough to support a Conservancy The Preserve is used for recreational genetically viable bison herd. In 1989 this activities such as hiking, photography, realization led to the purchase of the and nature observation. -

THE FLINT HILLS MARK FEIDEN and JIM HOY

THE FLINT HILLS MARK FEIDEN and JIM HOY THE FLINT HILLS MARK FEIDEN and JIM HOY LIMITED-EDITION, FINE-ART PRINTS AVAILABLE www.TheKonzaPress.com FIRST EDITION SPECIAL THANKS Photographs and introduction ©2011 by Mark Feiden Stephen Anderson Essay ©2011 by Jim Hoy Jack and Kay Ann Feiden Josh and Gwen Hoy Published by The Konza Press, a division of The Konza Media Group, Incorporated Pat Kehde Wichita, Kansas, U.S.A. Rhonda Nehring Jay Nelson www.TheKonzaPress.com Edward Robison ALL RIGHTS RESERVED. No part of this book may be reproduced David Uhlig without written permission from the publisher—except by a reviewer who may quote brief passages in a review. Printed in Kansas, United States of America Softcover: ISBN: 978-0-9774753-6-0 Hardcover: ISBN: 978-0-9774753-7-7 Of the 400,000 square miles of tallgrass prairie that once covered North America, less than 5% remains—primarily in the Flint Hills of eastern Kansas. INTRODUCTION Mark Feiden “United States to Nehring, Military Bounty Land Act of March 3, 1855, Register’s Office, Lecompton, Kansas Territory, August 1st 1859. Military Land Warrant No. 55847 ... has this day been located by John Sebastian Nehring upon the N. 1/2 of the S.E. 1/4 of the N.W. quarter of Section 9 in Township 13, Range 11.” Though the Sunday afternoon drive was very much a part of my childhood, and though I had participated in the occasional pilgrimage to visit relatives and see the “old home place,” my love affair with the tallgrass prairie didn’t begin in earnest until I enrolled at the University of Kansas. -

Osage-County-2018-Web-Version.Pdf

Pioneer Woman Lodge — Pawhuska Gilcrease Museum Gilcrease The Mercantile – Pawhuska e l i t n a c r e M POSTOAK Lodge & n a m o W r e e n o i P e h T Drive through the Tallgrass Prairie Preserve Retreat – Tulsa CR 3225 12 Grainola Hulah Lake Hulah 28 Wildlife CR 3575 Refuge Foraker CR 4600 CR 4650 Kaw Wildlife Osage Refuge John Dahl Wildlife Foraker Rd Wildlife Tallgrass Refuge Osage Refuge CR 4201 Wildlife Prairie Lake Reserve Refuge Webb CR 4420 Hudson City 2 Deer 36 Lake 38 Sunset 3851 CR CR 3102 Shidler Lake CR 3070 7 37 CR 3060 CR 3551Bartlesville Scenic Byway a m o h a l k O Osage Hills Burbank State Park Kaw Lake13 Landing Rd Bluestem CR 4201 3 9 POSTOAKOSA Canopy Tours (Zipline) – Tulsa Lake GE CO CR 2365 UNTY, O KLAHOMA Burbank CR 4020 Okesa Visit the Woolaroc Museum Kaw Dam Rd Pawhuska CR 4291 CR 4275 OkesaCR 2801 Rd Lookout Mountain Woolaroc Museum 15 CR & Wildlife 5 McCord Lake 5205 Preserve 48 Pawhuska Tulsa Botanic Garden 47 46 CR 2561 Fairfax City 44 Nelagoney Lake 43 10 42 Arkansas River 40 39 CR 2420 Fairfax Lake Rd 45 CR 2331 Fairfax 26 17 Lake CR 5451 Gray Horse 27 Waxhoma x Cemetery CR 2393 CR 2307 41 Wynona CR 2471 CR 2383 Gray CR 2350 Barnsdall Horse CR 2409 CR 2255 Tour the Drummond Historic Home – Hominy 8 Birch Lake Grand Ave TH Lodging Avant E DRUMMOND Barnsdall HOME Jeff Wade Saddle Shop and RV Park 704 West Main Street (918) 847-2286 35 Hominy Ranchland Rd Grandview Ave. -

Thematic Survey of Historic Barns in Northwestern Oklahoma

Thematic Survey of Historic Barns in Northwestern Oklahoma Alfalfa, Beaver, Cimarron, Ellis, Garfield, Grant, Harper, Kay, Major, Noble, Texas, Woods, and Woodward Counties Prepared for: OKLAHOMA HISTORICAL SOCIETY State Historic Preservation Office Oklahoma History Center 800 Nazih Zuhdi Drive Oklahoma City, Oklahoma 73105-7914 Prepared by: Brad A. Bays, Ph.D. Department of Geography 337 Murray Hall Oklahoma State University Stillwater, Oklahoma 74078-4073 1 Acknowledgment of Support The activity that is the subject of [type of publication] has been financed [in part/entirely] with Federal funds from the National Park Service, U.S. Department of the Interior. However, the contents and opinions do not necessarily reflect the views or policies of the Department of the Interior, nor does the mention of trade names or commercial products constitute endorsement or recommendation by the Department of the Interior. (Note that only relevant portions of the required statement need to be applied and should be used as appropriate depending on the content of the publications; e.g., if there are no commercial products, then that part of the statement can be omitted.) Nondiscrimination Statement This program receives Federal financial assistance for identification and protection of historic properties. Under Title VI of the Civil Rights Act or 1964, Section 504 of the Rehabilitation Act of 1973, and the Age Discrimination Act of 1975, as amended, the U.S. Department of the Interior prohibits discrimination on the basis of race, color, national origin, disability, or age in its federally assisted programs. If you believe you have been discriminated against in any program, activity, or facility as described above, or if you desire further information, please write to: Office of Equal Opportunity National Park Service 1849 C Street, N.W. -

HERITAGE of the GREAT PLAINS POLICY LIFE and LORE of the TALLGRASS PRAIRIE .Wary, Rolklore, Lul, Mwiic, Or Life in ; Welcomed

• HERITAGE OF THE GREAT PLAINS POLICY LIFE AND LORE OF THE TALLGRASS PRAIRIE .wary, rolklore, lUl, mWiic, or life in ; welcomed. Some poetry and short An Annotated Bibliography of the Flint Hills of Kansas by James Hoy 'the Greal PJQiflS should be typed and governed by The Chicago MOJ1uaI of Table or Contt'nis Part II, Natural History and Early Settlement 3 , • thort )'jUl on the aULhor. Tallgrass Ecology 3 c .cturaed only on request and when Flint Hills Fauna 7 I envelope. Flint Hills Flora 12 pin andJot illUSLratioDS with articles, Grass and Range Management 14 :cpt respoDSibility rOt photographs or Grass and Fire . .. 18 The Prairie Park 28 r the issue of the journal in which his Flint Hills Geology 32 Flint Hills Soils . JH ~e copies may be purchased (or $2.50 Water in the Flint Hills 39 Minerals in the Flint Hills 42 :d to: Caves in the Flint Hills 46 Archaeology, Pre-History, and NatIve Americans 47 Julie Johnson Explorers, Early Travelers, and Trails 55 HeriJQgt of the Oreal Plains Promotional Materials, Historical and Modern 59 Cenler ror Great Plains Studies Travel and Transportation _ , _ 62 Emporia State University The Flint Hills Overland Wagr>n Train 68 Emporia. Kansas 66801-5087 James IJo)', professor of English at Emporia State University is a native of Cassaday, Kansas. He received his B.S. degree from Kansas State University, the M.A. degree from Kansas State Teachers College, and the Ph.D. degree from the University of Missouri, Columbia. He is the author and coauthor of several books.