The National Committee's Campaign for a Comprehensive Law For

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Tenth Report

TENTH REPORT STANDING COMMITTEE ON DEFENCE (2001) (THIRTEENTH LOK SABHA) MINISTRY OF DEFENCE [Action Taken on the Recommendations contained in the 3rd Report of the Committee (Thirteenth Lok Sabha) on Demands for Grants (2000-2001) of the Ministry of Defence] Presented to Lok Sabha on 23 March, 2001 Laid in Rajya Sabha on 23 March, 2001 LOK SABHA SECRETARIAT NEW DELHI March, 2001/Chaitra, 1923 (Saka) CONTENTS COMPOSITION OF THE COMMITTEE (2001) INTRODUCTION CHAPTER I Report CHAPTER-II Recommendations/Observations which have been accepted by the Government CHAPTER III Recommendations/Observations which the Committee do not desire to pursue in view of Government's replies CHAPTER IV Recommendations/Observations in respect of which rplies of Government have not been accepted by the Committee CHAPTER V Recommendations/Observations in respect of which final replies of Government are still awaited MINUTES OF THE SITTING APPENDIX Analysis of Action Taken by Government on the Recommendations contained in the Third Report of the Standing Committee on Defence (Thirteenth Lok Sabha) on the Demands for Grants of the Ministry of Defence (2000-2001) COMPOSITION OF THE STANDING COMMITTEE ON DEFENE (2001) Dr. Laxmmarayan Pandey—Chairman MEMBERS Lok Sabha 2. Shri S. Ajaya Kumar 3. Shri Raj Babbar 4. Shri Vijayendra Pal Singh Badnore 5. Shri S. Bangarappa 6. Col. (Retd.) Sona Ram Choudhary 7. Smt. Sangeeta Kumari Singh Deo 8. Shri Jarborn Gamlin *9. Shri Indrajit Gupta 10. Shri Raghuvir Singh Kaushal 11. Shri Mansoor Ali Khan 12. Shri Chandrakant Khaire 13. Shri Vinod Khanna 14. Shri K.E. Krishnamurthy 15. Shri A. Krishnaswami 16. -

Raised a Discussion on the Statement Made by the Minister of Home Affairs Regarding Deportation of Certain People by Maharashtra Government

nt> Title: Raised a discussion on the statement made by the Minister of Home Affairs regarding deportation of certain people by Maharashtra Government. (Not concluded) 18.43 hrs. ºÉ¦ÉÉ{ÉÊiÉ ¨É½þÉänùªÉ : +¤É ÊxÉªÉ¨É 193 Eòä +ÆiÉMÉÇiÉ ¤É½þºÉ |ÉÉ®úÆ¦É ½þÉäiÉÒ ½þè* ¸ÉÒ¨ÉiÉÒ MÉÒiÉÉ ¨ÉÖJÉVÉÒÇ ¤É½þºÉ ¶ÉÖ°ü Eò®úäÆMÉÒ* SHRIMATI GEETA MUKHERJEE (PANSKURA): Hon. Chairman, Sir, my name is first in the list, but my brother Hannan Mollah has requested that he may be given the first chance to speak. I have agreed to that. His name is also there in the list. So, kindly call him first, and I will speak later. ¸ÉÒ ½þxxÉÉxÉ ¨ÉÉä±±Éɽþ (=±ÉÚ¤ÉäÊ®úªÉÉ) : ºÉ¦ÉÉ{ÉÊiÉ ¨É½þÉänùªÉ, ¨ÉèÆ +É{ÉEòÉ +ɦÉÉ®úÒ ½þÚÆ +Éè®ú MÉÒiÉÉ nùÒ EòÉ ¦ÉÒ ¤É½þÖiÉ +ɦÉÉ®úÒ ½þÚÆ ÊEò =x½þÉäÆxÉä ¨ÉÖZÉä <ºÉ Ê´É¹ÉªÉ EòÉä ¶ÉÖ¯û Eò®úxÉä EòÉ ¨ÉÉèEòÉ ÊnùªÉÉ* ¨ÉèÆ ¤É½þÖiÉ nùÖJÉ Eòä ºÉÉlÉ Eò½þxÉÉ SÉɽþiÉÉ ½þÚÆ ÊEò ¤ÉÆMÉɱÉÒ ¦ÉɹÉÉ ¤ÉÉä±ÉxÉä ´ÉɱÉä ±ÉÉäMÉÉäÆ EòÒ ºÉ¨ÉºªÉÉ +ÉVÉ xÉ<Ç xɽþÒÆ =`ö ®ú½þÒ ½þè* Ê{ÉUô±Éä ºÉÉiÉ-+É`ö ºÉÉ±É ºÉä ¨ÉèÆ <ºÉ ½þÉ=ºÉ ¨ÉäÆ +Eòä±ÉÉ ÊSɱ±ÉÉiÉÉ ®ú½þÉ ½þÚÆ* ... (´ªÉ´ÉvÉÉxÉ) Eò¦ÉÒ-Eò¦ÉÒ ÊEòºÉÒ xÉä VÉÉä<xÉ ÊEòªÉÉ ½þè, ½þ¨Éä¶ÉÉ xɽþÒÆ ÊEòªÉÉ* +É{ÉxÉä ¦ÉÒ ÊEòªÉÉ, <ºÉ ½þÉ=ºÉ ¨ÉäÆ ºÉ¤É ±ÉÉäMÉÉäÆ xÉä ÊEòªÉÉ* ¨ÉMÉ®ú ¤ÉÉiÉ ªÉ½þ ½þè ÊEò ªÉ½þ ºÉ´ÉÉ±É +ÉVÉ BäºÉÒ {ÉÊ®úʺlÉÊiÉ ¨ÉäÆ {ɽþÖÆSÉ SÉÖEòÉ ½þè ÊEò <ºÉEòä ¤ÉÉ®úä ¨ÉäÆ {ÉÉʱÉǪÉɨÉäÆ]õ ¨ÉäÆ BEò ºÉ½þ¨ÉÊiÉ, BEò ®úÉªÉ ¤ÉxÉxÉÉ ¤É½þÖiÉ VÉ°ü®úÒ ½þÉä MɪÉÉ ½þè* ¨ÉèÆ {ɽþ±Éä BEò ¤ÉÉiÉ ºÉÉ¡ò Eò®úxÉÉ SÉɽþÚÆMÉÉ ÊEò BEò <Æ]õ®úèº]õäb÷ E´ÉÉ]õÇ®ú ºÉä ±ÉMÉÉiÉÉ®ú ¤ÉÆMɱÉÉnùä¶ÉÒ +Éè®ú ¤ÉÆMɱÉɦÉɹÉÒ ¨ÉäÆ Eòx¡ªÉÚWÉ Eò®úxÉä EòÒ BEò EòÉäÊ¶É¶É ½þÉäiÉÒ -

“Sex Workers Meet Law Makers” 1St March 2011, Constitution Club, New Delhi

“Sex Workers Meet Law Makers” 1st March 2011, Constitution Club, New Delhi Background India is home to an estimated 12.63 lakh female sex workers. In addition, there are considerable numbers of male and transgender persons engaging in sex work. The last two decades has seen the emergence of sex workers’ collectives, mobilizing around health, education, livelihood and social security, and protection from violence. To illustrate, sex workers’ in Kolkata have developed the renowned peer education model of prevention of HIV, built schools for their children’s education and opened banks and credit facilities to reduce indebtedness. In Mysore, sex workers run a popular restaurant, dispelling the social stigma attached to sex work. In Bengaluru, sex workers have formed a trade union and are demanding labour standards. Sex workers in Sangli use film and theatre medium of ‘Sangli Talkies’ to articulate their experiences to the world at large. Across the country, sex workers’ are asserting themselves in public spaces and claiming equal opportunity before law. While the above examples mark a welcome break from disempowerment, sex workers’ efforts to improve their lives are obscured by criminalization. Prostitution per se is not illegal but sex workers’ are restrained under the Immoral Traffic (Prevention) Act, 1956 (ITPA) with dangerous consequences for the health, safety, livelihood and protection of sex workers. Between 2005-2009, sex workers engaged with Members of Parliament (MPs), including the then Minister of Women and Child Development, senior officials from the National AIDS Control Organisation and the Ministry of Health, the Parliamentary Standing Committee on Women and Child Development and the Forum of Parliamentarians on HIV and AIDS to share their concerns on the proposed amendments to ITPA. -

Annex I-A Notification

Annexes 179 ANNEX I-A No.F. 34/6/49-Public GOVERNMENT OF INDIA MINISTRY OF HOME AFFAIRS New Delhi, the 16th May, 1949 NOTIFICATION The Governor General is pleased to announce the creation with immediate effect of a Department of Parliamentary Affairs under the Minister of State for Parliamentary Affairs. This Department will take over from the Ministry of Law the work in connection with the functions of the Government Chief Whip and other Parliamentary Affairs. Sd: H.V.R. IENGER SECRETARY TO THE GOVERNMENT OF INDIA 180 Handbook on the Working of Ministry of Parliamentary Affairs ANNEX I-B ALLOCATION OF FUNCTIONS TO THE MINISTRY OF PARLIAMENTARY AFFAIRS 1. Dates of summoning and prorogation of the two Houses of Parliament: Dissolution of Lok Sabha, President’s Address to Parliament. 2. Planning and coordination of Legislative and other Official Business in both Houses. 3. Allocation of Government time in Parliament for discussion of Motions given notice of by Members. 4. Liaison with Leaders and Whips of various Parties and Groups represented in Parliament. 5. Lists of Members of Select and Joint Committees on Bills. 6. Appointment of Members of Parliament on Committees and other bodies set up by Government. 7. Functioning of Consultative Committees of Members of Parliament for various Ministries. 8. Implementation of assurances given by Ministers in Parliament. 9. Government’s stand on Private Members’ Bills and Resolutions. 10. Secretarial assistance to the Cabinet Committee on Parliamentary Affairs. 11. Advice to Ministries on procedural and other parliamentary matters. 12. Coordination of action by Ministries on the recommendations of general application made by parliamentary committees. -

229 Writton Answers AGRAHAYANA (A) Whether the Navy Has Any Plans

229 Writton Answers AGRAHAYANA 1,1913 {SAKA) Wrkten Answers 230 (a) whether the Navy has any plans to aware that jute growers have been com- extended the runway as well as to provide pelled to sell their production betow the night landing facilites at Visakhapatnam air- minimum support price this year due to non- port to enable the Airbus to become opera- intervention by the Jute Corporation of India; tional to meet the passenger-traffic demand; and (b) if so, the reasons for non-interoen- tion by the JCI; (b) if so, the details thereof? (c) the quantum of raw jute purchased THE [\^INISTER OF STATE OF THE by the JCI in the current jute season till date MINISTRY OF DEFENCE (SHRI SHARAD against the total production State-wise; and PAWAR): (a) and (b). Yes, Sir. There are plans to re-orient/extend the secondary (d) the steps being taken by the Govern- runway at the Visakhapatnam Airport, sub- ment to stem the prices of raw jute at reason- ject to the availability of land for the purpose able level? from the Visakhapatnam Port Trust. In the meantime, action has been initiated to pro- THE MINISTER OF STATE OF THE vide night landing facilities on the existing MINISTRY OF TEXTILES (ASHOK runway. GEHLOT): (a) and (b). Jute growers have not been compelled to sell their produce below minimum support prices due to timely Procurement of Raw Jute by JCI market intervention of JCI whenever prnes of raw jute touched minimum support levels 313. SHRI HANNAN MOLLAH: as per report. SHRI INDRAJIT GUPTA: SHRI CHITTA BASU; (c) and (d). -

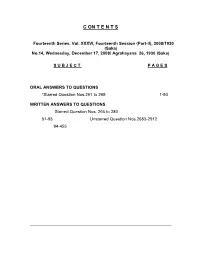

C on T E N T S

C ON T E N T S Fourteenth Series, Vol. XXXVI, Fourteenth Session (Part-II), 2008/1930 (Saka) No.14, Wednesday, December 17, 2008/ Agrahayana 26, 1930 (Saka) S U B J E C T P A G E S ORAL ANSWERS TO QUESTIONS *Starred Question Nos.261 to 265 1-50 WRITTEN ANSWERS TO QUESTIONS Starred Question Nos. 266 to 280 51-93 Unstarred Question Nos.2683-2912 94-455 * The sign + marked above the name of a Member indicates that the Question was actually asked on the floor of the House by that Member. PAPERS LAID ON THE TABLE 456-491 MESSAGES FROM RAJYA SABHA 492-493 ESTIMATES COMMITTEE 19th and 20th Reports 494 PUBLIC ACCOUNTS COMMITTEE 78th to 80th Reports 494 COMMITTEE ON PETITIONS 43rd to 45th Reports 495 STANDING COMMITTEE ON HUMAN RESOURCE DEVELOPMENT 212th Report 496 STATEMENT BY MINISTERS 497-508 (i) Status of implementation of the recommendations contained in the 70th Report of the Standing Committee on Finance on Demands for Grants (2008-09), pertaining to the Ministry of Statistics and Programme Implementation. Shri G.K. Vasan 497-499 (ii) Status of implementation of the recommendations contained in the 204th Report of the Standing Committee on Human Resource Development on Demands for Grants (2007-08), pertaining to the Ministry of Youth Affairs and Sports. Dr. M.S. Gill 500 (iii) Status of implementation of the (a) recommendations contained in the 23rd Report of the Standing Committee on Personnel, Public Grievances, Law and Justice on the Government's policy of appointment on compassionate ground, pertaining to the Ministry of Personnel, Public Grievances and Pensions (b) Status of implementation of the recommendations contained in the 189th Report of the Standing Committee on Science and Technology, Environment and Forests on Demands for Grants (2008-09), pertaining to the Department of Space. -

Olitical Amphlets from the Indian Subcontinent Parts 1-4

A Guide to the Microfiche Edition of olitical amphlets from the Indian Subcontinent Parts 1-4 UNIVERSITY PUBLICATIONS OF AMERICA fc I A Guide to the Microfiche Collection POLITICAL PAMPHLETS FROM THE INDIAN SUBCONTINENT Editorial Adviser Granville Austin Associate Editor and Guide compiled by August A. Imholtz, Jr. A microfiche project of UNIVERSITY PUBLICATIONS OF AMERICA An Imprint of CIS 4520 East-West Highway • Bethesda, MD 20814-3389 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publicaîion Data: Indian political pamphlets [microform] microfiche Accompanied by a printed guide. Includes bibliographical references. ISBN 1-55655-206-8 (microfiche) 1. Political parties-India. I. UPA Academic Editions (Firm) JQ298.A1I527 1989<MicRR> 324.254~dc20 89-70560 CIP International Standard Book Number: 1-55655-206-8 UPA An Imprint of Congressional Information Service 4520 East-West Highway Bethesda, MD20814 © 1989 by University Publications of America Printed in the United States of America The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Information Sciences-Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI Z39.48-1984. TABLE ©F COMTEmn Introduction v Note from the Publisher ix Reference Bibliography Part 1. Political Parties and Special Interest Groups India Congress Committee. (Including All India Congress Committee): 1-282 ... 1 Communist Party of India: 283-465 17 Communist Party of India, (Marxist), and Other Communist Parties: 466-530 ... 27 Praja Socialist Party: 531-593 31 Other Socialist Parties: -

Lok Sabha Debates

Seventh Series9ROI1R. 4 Thursday, January 24, 1980 Magha 04, 1901 6DND /2.6$%+$ '(%$7(6 First Session Seventh/RN6DEKD 9ROI CRQWDLQV1R1WR10 /2.6$%+$6(&5(7$5,$7 1(:'(/+, 3ULFH5V CONTENT o. 4-Thur day January 24 1980/Magba 4, 1901 (Saka) MEMBERS SWORN COLUMNS Re. Calling Attention Notices, etc. 1-5, 6- 12 PAPERS LAID ON THE TABLE ...... 5-6, 13-· 18 Calling AttePtion To Matter Of Urgent Public Importan e- Reported situation arising out of Violent agitation in Assam and Meghalaya 19- Shri Amar Roy Pradhan 19, 22-24 Shri P. Venkatasubbaiah 19-22 Shrimati Indira Gandhi 25-2 6 Shri Somnath Chatterjee 26 31 Shri Zail Singh 3J -34 Shri M, Ramanna Rai Shri K. A. Rajan . Contingency Fund of India (Amendment) Bill-Introduced Shri R. Venkataraman . 39 Statement reo Contingency Fund of India (Amendment) Ordinance Shri R. Venkataraman Matters Under Rule 377 (i) Shortage of Neptha with Barauni Fertilizer Factory Shrimati Krishna Sahi (ii) Problems of Indians in United Arab Emirate Dr. Vasant Kumar Pandit . 40 (iii) Cases of Robberies in Delhi Shri H. K. L. Bhagat (iv) Issue of notification about increase in tb.e price of fabricated Mica hri R.L.P. Verma 41 (v) Reported lock-out in Kesoram Cotton Mills ~ Shri Jyotirmoy Bosu 2346 L.S.-l ii Constitution (Forty-Fifth Amendment) Bill- COLUMNS Motion to consider . .... 43-121 Shri Zail Singh 44-· 45, 77-81 Shri Jaipal Singh Kashyap 45-47 Shri Krishna Chandra Halder 47-48 Shri Kusuma Krishna Murthy 48-52 Shri Bapusaheb Parulekar 52-. 55 Shri Buta Singh . -

Ie-Mumbai-05-01-2021.Pdf

DAILY FROM: AHMEDABAD,CHANDIGARH, DELHI, JAIPUR, KOLKATA,LUCKNOW, MUMBAI, NAGPUR, PUNE, VADODARA ● REG.NO. MCS/067/2018-20RNI REGN. NO. 1543/57 JOURNALISM OF COURAGE TUESDAY, JANUARY 5, 2021, MUMBAI, LATE CITY, 14 PAGES SINCE 1932 `5.00, WWW.INDIANEXPRESS.COM NEGOTIATIONS TO RESUME ON JANUARY 8 Covaxin to protect Talksinconclusive:Farmersinsiston against mutants, repeal,Govtforclause-wisediscussion data in aweek: Tomar says BharatBiotech hopeful, 2Punjab PRABHARAGHAVAN ED BJPleaders to NEWDELHI,JANUARY4 Extrashot meetPMtoday PLAIN E ● inarsenal BUSINESSASUSUAL THE HEAD of Bharat Biotech ex- EX pressedconfidence at apress BY UNNY RAAKHIJAGGA& conference on Mondaythat AMID CONCERNS that HARIKISHANSHARMA Covaxin, the vaccine candidate Covaxin had been given LUDHIANA,NEWDELHI,JAN4 developedbythe company, will emergency use authori- be effective on mutant strains of sation without full data, TALKSBETWEEN the Centre the novelcoronavirus —amajor Health MinisterDrHarsh and farmer unions opposedto reason whythe candidatehas Vardhan has clarified the newagriculture laws re- been granted approval forre- that this wasa“strategic mainedinconclusive Monday stricted use. decision”. “...Thisap- over twokey demands —repeal The companywill be able to proval ensures India has of the newlyenacted laws and establishthe “hypothesis” of the an additional vaccine provision of legal guarantee on candidate's ability to protect shieldinits arsenal esp the minimum supportprice — againstmutations in aweek, againstpotential mutant with the twosides drawingthe chairmanand managing direc- strains in adynamic pan- hardlineontheir respectivepo- Women being trainedtodrive tractors, on the Jind-Patiala national highway on Monday. Express torDrKrishna Ella said. demic situation -A sitions. “It’s onlyahypothesis right strategic decision forour BMC to start The talkswill resume on now...but justgivemeone vaccine security,”he January8when the twosides sit week’stime (and) I’ll give confir- postedonTwitter. -

List of Successful Candidates

Election Commission Of India - General Elections, 2004 (14th LOK SABHA) LIST OF SUCCESSFUL CANDIDATES CONSTITUENCY WINNER PARTY ANDHRA PRADESH 1. SRIKAKULAM YERRANNAIDU KINJARAPU TDP 2. PARVATHIPURAM (ST) KISHORE CHANDRA SURYANARAYANA DEO INC VYRICHERLA 3. BOBBILI KONDAPALLI PYDITHALLI NAIDU TDP 4. VISAKHAPATNAM JANARDHANA REDDY NEDURUMALLI INC 5. BHADRACHALAM (ST) MIDIYAM BABU RAO CPM 6. ANAKAPALLI CHALAPATHIRAO PAPPALA TDP 7. KAKINADA MALLIPUDI MANGAPATI PALLAM RAJU INC 8. RAJAHMUNDRY ARUNA KUMAR VUNDAVALLI INC 9. AMALAPURAM (SC) G.V. HARSHA KUMAR INC 10. NARASAPUR CHEGONDI VENKATA HARIRAMA JOGAIAH INC 11. ELURU KAVURU SAMBA SIVA RAO INC 12. MACHILIPATNAM BADIGA RAMAKRISHNA INC 13. VIJAYAWADA RAJAGOPAL LAGADAPATI INC 14. TENALI BALASHOWRY VALLABHANENI INC 15. GUNTUR RAYAPATI SAMBASIVA RAO INC 16. BAPATLA DAGGUBATI PURANDARESWARI INC 17. NARASARAOPET MEKAPATI RAJAMOHAN REDDY INC 18. ONGOLE SREENIVASULU REDDY MAGUNTA INC 19. NELLORE (SC) PANABAKA LAKSHMI INC 20. TIRUPATHI (SC) CHINTA MOHAN INC 21. CHITTOOR D.K. AUDIKESAVULU TDP 22. RAJAMPET ANNAYYAGARI SAI PRATHAP INC 23. CUDDAPAH Y.S. VIVEKANANDA REDDY INC 24. HINDUPUR NIZAMODDIN INC 25. ANANTAPUR ANANTHA VENKATA RAMI REDDY INC 26. KURNOOL KOTLA JAYASURYA PRAKASHA REDDY INC 27. NANDYAL S. P. Y. REDDY INC 28. NAGARKURNOOL (SC) DR.MANDA JAGANNATH TDP 29. MAHABUBNAGAR D. VITTAL RAO INC 30. HYDERABAD ASADUDDIN OWAISI AIMIM 31. SECUNDERABAD M. ANJAN KUMAR YADAV INC 32. SIDDIPET (SC) SARVEY SATHYANARAYANA INC 33. MEDAK A. NARENDRA TRS 34. NIZAMABAD MADHU GOUD YASKHI INC 35. ADILABAD MADHUSUDHAN REDDY TAKKALA TRS 36. PEDDAPALLI (SC) G. VENKAT SWAMY INC 37. KARIMNAGAR K. CHANDRA SHAKHER RAO TRS 38. HANAMKONDA B.VINOD KUMAR TRS 39. WARANGAL DHARAVATH RAVINDER NAIK TRS 40. -

Members of Newly Elected 13Th Lok Sabha Made and Subscribed the Oath Or Affirmation

Title: Members of newly elected 13th Lok Sabha made and subscribed the oath or affirmation . [Mr. Speaker in the Chair) MR. SPEAKER: The Secretary-General may please call out the names of those Members who have not yet taken the oath or made the affirmation. MEMBERS SWORN - Contd. Kumari Uma Bharati (Bhopal) Shri V. Sreenivasaprasad (Chamarajanagar) Shri I.D. Swamy (Karnal) Shrimati Dumpa Mary Vijaya Kumari (Bhadrachalam) Shrimati Renuka Chowdhury (Khammam) Shri Braj Mohan Ram (Palamau) SHRI MADHAVRAO SCINDIA (GUNA): Sir, would you give me an opportunity to make a suggestion? MR. SPEAKER: What suggestion do you want to make? SHRI MADHAVRAO SCINDIA : Sir, I just want to make a suggestion, through your esteemed good offices, to the Government that after all the hon. Members have taken oaths and before the House adjourns today, we could be given an opportunity to pay tribute to President Nyrere who was a giant on the world stage and who was also a great friend of India. This is my suggestion. You can consider it. MR. SPEAKER: We will consider your suggestion. MEMBERS SWORN - Contd. Shri Ratilal Kalidas Verma (Dhandhuka) Shri H.G. Ramulu (Koppal) Shri G. Mallikarjunappa (Davangere) Shri Srikantadatta Narasimharaja Wadiyar (Mysore) Shri D.C. Srikantappa (Chikmagalur) Shri Ashok Chhaviram Argal (Morena) Dr. Ramlakhan Singh (Bhind) Shri Chandra Pratap Singh (Sidhi) Shri Khel Sai Singh (Surguja) Shri Vishnudeo Sai (Rajgarh) Dr. Charandas Mahant (Janjgir) Shri Sohan Potai (Kanker) Shri Baliram Kashyap (Bastar) Shri Prahladsingh Patel (Balaghat) -

Papers Laid on the Table

293 Papers Laid 29 KARTIKA, 1919(54/04) Papers Laid 294 11.36 hrs. MR. SPEAKER: KumariMamataBanerjee, why cannot you keep quiet for a mement? Please sit down. PAPERS LAID ON THE TABLE .... (Interruptions) MR. SPEAKER : The Home Minister may place the Report on the Table of the House. MR. SPEAKER .ShriTopdar, will you kindly sit down? SHRI SOMNATH CHATTERJEE (Bolpur): Sir, I have ...(Interruptions) no objection for his placing the Report. But there is only the suspension of the Question Hour. The question of Motion MR. SPEAKER : Shri Gaikwad, now please sit down. being taken up for discussion is not there. You are not supposed to direct them. MR. SPEAKER: No. That Motion will not be taken up. ...(Interruptions) I am calling upon him only to lay the Report on the Table of the House. MR. SPEAKER : Enough is enough. .... (Interruptions) Mr. Home Minister, please. SHRI AJIT KUMAR PANJA (Calcutta North-East) : Interim Report of One-man Commission of Inquiry What do your mean by ‘part of the conspiracy’? You are under Commission of Inquiry Act, 1952 doing character assassination .....(Interruptions) THE MINISTER OF HOME AFFAIRS (SHRI INDRAJIT MR. SPEAKER: Now, nothing more. Why are you GUPTA): Mr. Speaker, Sir, as directed by you, I beg for making noise now? You have got what you wanted. Please leave to lay on the Table: keep quite. (1) A copy each of the following papers (In English .... (Interruptions) version only) under Sub-Section(4) of Section 3 of the Commission of Inquiry Act, 1952: SHRI RUPCHAND PAL(Hooghly): He should withdraw his words ...