Lenses the Nimrud Lens

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

PETZVAL's LENS and CAMERA by Rudolf Kingslake

PETZVAL'S LENS AND CAMERA by Rudolf Kingslake Joseph Max Petzval was born on January 6, 1807, in Hungary of German parentage; he died 84 years later in September 1891. Being a member of the mathematics faculty of the University of Vienna, he naturally approached the problem of lens design from a mathematical rather than from an empir ical standpoint, which probably accounted in part for his suc cess. He actually designed two lenses in 1839, the Portrait lens which he immediately commissioned P. F. von Voigtlander to make, and the Orthoscopic lens which was not manufactured T THE OFFICIAL ANNOUNCEMENT of the Daguerreotype until 1856. Petvzal's interest in optics continued throughout the A process in 1839, Austria was represented by Professor A. rest of his life, and he reported in 1843 that "by order of the F. von Ettingshausen. He was so impressed with the possibilities General-Director Archduke Ludwig, he was assisted in his of photography that upon his return to Vienna, he induced his calculations for several years by two officers and eight friend and colleague the mathematician Joseph Petzval to undertake the design of a wide-aperture lens suitable for por traiture. Petzval, then 33 years old, devoted himeslf enthusiasti cally to the problem and was amazingly successful. He used a well-corrected telescope objective the right way round for his front component, and added an airspaced doublet behind it, the rear doublet being mathematically designed to give sharp de finition and to flatten the field. The formula was handed to the old-established Viennese optician Voigtlander, who first supplied the lens to a focal length of 150 mm and an aperture of f/3.6, mounted in a conical metal camera having a circular ground-glass focusing screen 94 mm diameter with a focusing magnifier permanently installed behind it. -

Portraiture, Surveillance, and the Continuity Aesthetic of Blur

Michigan Technological University Digital Commons @ Michigan Tech Michigan Tech Publications 6-22-2021 Portraiture, Surveillance, and the Continuity Aesthetic of Blur Stefka Hristova Michigan Technological University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.mtu.edu/michigantech-p Part of the Arts and Humanities Commons Recommended Citation Hristova, S. (2021). Portraiture, Surveillance, and the Continuity Aesthetic of Blur. Frames Cinema Journal, 18, 59-98. http://doi.org/10.15664/fcj.v18i1.2249 Retrieved from: https://digitalcommons.mtu.edu/michigantech-p/15062 Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.mtu.edu/michigantech-p Part of the Arts and Humanities Commons Portraiture, Surveillance, and the Continuity Aesthetic of Blur Stefka Hristova DOI:10.15664/fcj.v18i1.2249 Frames Cinema Journal ISSN 2053–8812 Issue 18 (Jun 2021) http://www.framescinemajournal.com Frames Cinema Journal, Issue 18 (June 2021) Portraiture, Surveillance, and the Continuity Aesthetic of Blur Stefka Hristova Introduction With the increasing transformation of photography away from a camera-based analogue image-making process into a computerised set of procedures, the ontology of the photographic image has been challenged. Portraits in particular have become reconfigured into what Mark B. Hansen has called “digital facial images” and Mitra Azar has subsequently reworked into “algorithmic facial images.” 1 This transition has amplified the role of portraiture as a representational device, as a node in a network -

Sky & Telescope

S&T Test Report by Rod Mollise Meade’s 115-Millimeter ED Triplet This 4.5-inch apochromat packs a lot of bang for the buck. 115mm Series 6000 THIS IS A GREAT TIME to be in the ice and was eager to see how others market for a premium refracting tele- performed. So when I was approached ED Triplet APO scope. The price for high-quality refrac- about evaluating Meade’s 115mm Series U.S. Price: $1,899 tors has fallen dramatically in recent 6000 ED Triplet APO, I was certainly up meade.com years, and you can now purchase a for the task. 4- to-5-inch extra-low dispersion (ED) First impressions are important, and What We Like apochromatic (APO) telescope that’s when I unboxed the scope on the day Sharp, well-corrected optics almost entirely free of the false color it arrived, I lit up when I saw it. This is Color-free views that plagues achromats for a fraction of Attractive fi nish the cost commonly seen a decade ago. I’ve had a ball with my own recently q The Meade 115mm Series 6000 ED Triplet What We Don’t Like purchased apochromat after using APO ready for a night’s activity, shown with an optional 2-inch mirror diagonal. The scope Visual back locking almost nothing but Schmidt-Cassegrain also accepts fi nderscopes that attach using a system can be awkward telescopes for many years. However, I standardized dovetail system commonly found Focuser backlash still consider myself a refractor nov- on small refractors. -

Owner's Manual

VQT4G28_ENG_SPA.book 1 ページ 2012年5月16日 水曜日 午前11時43分 Owner’s Manual INTERCHANGEABLE LENS FOR DIGITAL CAMERA Model No. H-HS12035 Before connecting, operating or adjusting this product, please read the instructions completely. For USA and Puerto Rico assistance, please call: 1-800-211-PANA(7262) or, contact us via the web at: http://www.panasonic.com/contactinfo For Canadian assistance, please call: 1-800-99-LUMIX (1-800-995-8649) or send e-mail to: [email protected] VQT4G28 PP F0512SM0 until 2012/6/6 VQT4G28_ENG_SPA.book 2 ページ 2012年5月16日 水曜日 午前11時43分 Contents THE FOLLOWING APPLIES ONLY IN CANADA. Information for Your Safety..................................... 2 This Class B digital apparatus complies with Precautions........................................................... 4 Canadian ICES-003. Supplied Accessories ............................................. 5 Attaching/Detaching the Lens................................. 6 Names and Functions of Components ................... 8 Cautions for Use..................................................... 9 Information for Your Safety Troubleshooting .................................................... 9 Specifications........................................................ 10 Keep the unit as far away as possible from Limited Warranty................................................... 11 electromagnetic equipment (such as microwave ovens, TVs, video games, radio transmitters, -If you see this symbol- high-voltage lines etc.). ≥ Do not use the camera near cell phones because Information -

With Its Focal Length Shorter Than That of the Normal Lens, the Wideangle Lenses Cover an Angle of View of 60° Or More. The

With its focal length shorter than that of the normal lens, the wideangle lenses cover an angle of view of 60° or more. The wideangle lens allows coverage of quite a broad view from a close camera position or photography in constricted areas. It can be effectively utilized in architectural exteriors and interiors and group shots. The wideangle lens is also suited for instant candid work which does not allow precise focusing on fast-moving subjects. Its profound depth of field compensates for inaccurate focusing. Another outstanding feature of the wideangle lens is exaggeration of perspective. This type of lens tends to give an interesting and dramatic effect which is more conspicuous, the wider the angle of lens. Today, "Wideangle Shooting" occupies a unique place in creative photography. Advanced photographers often emphasize the exaggerated perspective known as "wideangle distortion" to accomplish special creative effects. Nikon offers one of the widest selections of outstanding wideangle lenses to meet specific photographic requirements in wide field photography. L-15 20mm f/3.5 Nikl<or-UD Auto Code No. 108-01-105 The concept of optical construction is entirely new. Focal length: 20mm The lens consists of 11 elements in 9 groups, with Maximum aperture: 1 : 3.5 Lens construction: 11 elements in 9 groups back focus 1.87 times longer than the focal length. Picture angle: 94° Thus, the lens can be mounted on the camera with Distance scale: Graduated both in meters and feet up to the mirror in normal viewing position. (There is no 0.3m and 1ft f/3.5 - f / 22 need to lock up the mirror.) Aperture scale: Aperture diaphragm: Fully automatic With this lens, there is almost no need to focus, if Meter coupling prong: Integrated (fully open exposure metering) the diaphragm is closed down slightly. -

Choosing Digital Camera Lenses Ron Patterson, Carbon County Ag/4-H Agent Stephen Sagers, Tooele County 4-H Agent

June 2012 4H/Photography/2012-04pr Choosing Digital Camera Lenses Ron Patterson, Carbon County Ag/4-H Agent Stephen Sagers, Tooele County 4-H Agent the picture, such as wide angle, normal angle and Lenses may be the most critical component of the telescopic view. camera. The lens on a camera is a series of precision-shaped pieces of glass that, when placed together, can manipulate light and change the appearance of an image. Some cameras have removable lenses (interchangeable lenses) while other cameras have permanent lenses (fixed lenses). Fixed-lens cameras are limited in their versatility, but are generally much less expensive than a camera body with several potentially expensive lenses. (The cost for interchangeable lenses can range from $1-200 for standard lenses to $10,000 or more for high quality, professional lenses.) In addition, fixed-lens cameras are typically smaller and easier to pack around on sightseeing or recreational trips. Those who wish to become involved in fine art, fashion, portrait, landscape, or wildlife photography, would be wise to become familiar with the various types of lenses serious photographers use. The following discussion is mostly about interchangeable-lens cameras. However, understanding the concepts will help in understanding fixed-lens cameras as well. Figures 1 & 2. Figure 1 shows this camera at its minimum Lens Terms focal length of 4.7mm, while Figure 2 shows the110mm maximum focal length. While the discussion on lenses can become quite technical there are some terms that need to be Focal length refers to the distance from the optical understood to grasp basic optical concepts—focal center of the lens to the image sensor. -

LENSES There Is Something Magical About the Image Formed by a Lens

LENSES There is something magical about the image formed by a lens. Surely every serious photographer stands in awe of this miraculous device, which approaches ultimate perfection. A fine lens is evidence of a most advanced technology and craft. We must come to know intuitively what our lenses and other equipment will do for us, and how to use them. ~ Ansel Adams LENSES A pinhole is the simplest way to form an image. A pinhole creates a very soft focused, diffused image that is often aesthetically pleasing. Pinhole cameras can be very complex or very simple in construction. ~ Ansel Adams LENSES Focal Length When choosing a camera you must also choose the appropriate lens for whatever subject matter you will be photographing. Lenses come in a wide variety, not only in focal length but also in price. Purchasing the right lens can be difficult if you don’t understand some basic terminology: Focal Length is what gives lenses their names (wide, telephoto, zoom, etc). The focal length is defined as a distance from the center of such a convex element (principle point) to the focal point (image plane) and it is one of the most decisive factors that determines the characteristics of a lens. When purchasing a lens we recognize the focal length of the lens sometimes by its physical length, but mainly by the number designated. For example: 50mm, 85mm, 200mm, 70-200mm, etc. The focal length is usually the first decision to make in purchasing a lens. Focal Length LENSES One of the greatest advantages to purchasing a digital SLR camera is the fact that you can purchase a wide variety of lens for every purpose. -

The Camera Versus the Human Eye

The Camera Versus the Human Eye Nov 17, 2012 ∙ Roger Cicala This article was originally published as a blog. Permission was granted by Roger Cicala to re‐ publish the article on the CTI website. It is an excellent article for those police departments considering the use of cameras. This article started after I followed an online discussion about whether a 35mm or a 50mm lens on a full frame camera gives the equivalent field of view to normal human vision. This particular discussion immediately delved into the optical physics of the eye as a camera and lens — an understandable comparison since the eye consists of a front element (the cornea), an aperture ring (the iris and pupil), a lens, and a sensor (the retina). Despite all the impressive mathematics thrown back and forth regarding the optical physics of the eyeball, the discussion didn’t quite seem to make sense logically, so I did a lot of reading of my own on the topic. There won’t be any direct benefit from this article that will let you run out and take better photographs, but you might find it interesting. You may also find it incredibly boring, so I’ll give you my conclusion first, in the form of two quotes from Garry Winogrand: A photograph is the illusion of a literal description of how the camera ‘saw’ a piece of time and space. Photography is not about the thing photographed. It is about how that thing looks photographed. Basically in doing all this research about how the human eye is like a camera, what I really learned is how human vision is not like a photograph. -

Imaging Foto 2009

€ 4,– • ISSN 1430 - 1121 • 38. Jahrgang • 30605 7 imaging foto 2009 Fachzeitschrift für die Fotobranche • www.worldofphoto.de Casio: Bis zu 1.000 Fotos mit der Fotobücher: Immer mehr Varianten, Gesellschafterversammlung EXILIM EX-H10 mit denen der Verkauf Spaß macht Ringfoto: Premiere statt Krise Das Leichtgewicht mit der großen Ausdauer: Die Kamera Die gute Auftragslage bei Fotobüchern bereitet Positive Ergebnisse für Zentrale und Mitglieder, mit 24–240 mm Weitwinkel-Objektiv, neuem Landschafts- Handel, Großfinishern und klassischen Druckereien erfreuliche Perspektiven und eine exklusive Modus und HD-Video-Funktion verfügt über eine überaus derzeit große Freude. Die Vielzahl der Fotobuch- Weltpremiere sorgten auf der diesjährigen Gesell- beeindruckende Akkukapazität. S. 16 Varianten begeistert immer mehr Zielgruppen. S. 24 schafterversammlung für gute Stimmung. S. 28 CEWE FOTOBUCH KLEIN gemäß Preisliste, zzgl. Bearbeitungspauschale. Unverbindliche Preisempfehlung für ein * Testsieger in Serie! Das Original vom Marktführer – über 1 Mio. Kunden sind begeistert! Download kostenlos unter: www.cewe-fotobuch.de sd_fb_anz210x297+fotocontact+hae1 1 21.01.2009 11:58:21 Uhr Editorial Die Arcandor Insolvenz betrifft auch Foto Quelle Sortiment digitaler Bildprodukte auf- Vorerst geht gebaut und auch die eine oder ande- re pfiffige Neuheit präsentiert. Quelle Sprecher Manfred Gawlas es weiter hat im Rahmen der Zahlungsunfähig- Nachdem die Foto- und Imagingbranche bislang von spekta- keit der weiteren Arcandor Töchter von „strategischen Insolvenzen“ ge- kulären Effekten der Wirtschafts- und Finanzkrise verschont sprochen. Man kann darüber spe- geblieben ist, zeigte der Insolvenzantrag der Arcandor Gruppe kulieren, was mit dieser Formulierung nach neun Tagen doch seine Auswirkungen: Am 17. Juni gemeint ist – konservative Kaufleute meldeten 15 weitere Tochtergesellschaften des Konzerns bei gingen bislang davon aus, dass man den zuständigen Amtsgerichten ihre Zahlungsunfähigkeit – einen Insolvenzantrag nur dann stellt, darunter auch die Foto Quelle GmbH, Fürth. -

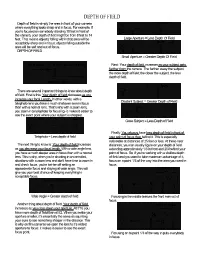

DEPTH of FIELD Depth of Field Is Simply the Area in Front of Your Camera Where Everything Looks Sharp and in Focus

DEPTH OF FIELD Depth of field is simply the area in front of your camera where everything looks sharp and in focus. For example, if you're focused on somebody standing 10 feet in front of the camera, your depth of field might be from 8 feet to 14 feet. That means objects falling within that area will be Large Aperture = Less Depth Of Field acceptably-sharp and in focus; objects falling outside the area will be soft and out of focus. DEPTH OF FIELD Small Aperture = Greater Depth Of Field Next: Your depth of field increases as your subject gets farther from the camera. The farther away the subject, the more depth of field; the closer the subject, the less depth of field. There are several important things to know about depth of field. First is this: Your depth of field decreases as you increase your focal Length. In other words, with a Disatant Subject = Greater Depth of Field telephoto lens you have a much shallower area in focus than with a normal lens. That's why with a zoom lens, you zoom in to telephoto for focusing--it makes it easier to see the exact point where your subject is sharpest. Close Subject = Less Depth of Field Finally: You always have less depth of field in front of Telephoto = Less depth of field your point of focus than behind it. This is especially noticeable at distances of 25 feet or less. At these near The next thing to know is: Your depth of field increases distances, you can usually figure on your depth of field as you decrease your focal length. -

Operating Instructions INTERCHANGEABLE LENS for DIGITAL CAMERA

VQT3R89_ENG_SPA.book 1 ページ 2011年8月2日 火曜日 午前10時48分 Operating Instructions INTERCHANGEABLE LENS FOR DIGITAL CAMERA Model No. H-PS45175 Before connecting, operating or adjusting this product, please read the instructions completely. For USA and Puerto Rico assistance, please call: 1-800-211-PANA(7262) or, contact us via the web at: http://www.panasonic.com/contactinfo For Canadian assistance, please call: 1-800-99-LUMIX (1-800-995-8649) or PP send e-mail to: [email protected] VQT3R89 until 2011/10/3 VQT3R89_ENG_SPA.book 2 ページ 2011年8月2日 火曜日 午前10時48分 Contents THE FOLLOWING APPLIES ONLY IN CANADA. Information for Your Safety..................................... 2 This Class B digital apparatus complies with Precautions........................................................... 4 Canadian ICES-003. Supplied Accessories ............................................. 5 Attaching/Detaching the Lens................................. 5 Names and Functions of Components ................... 7 Cautions for Use..................................................... 9 Information for Your Safety Troubleshooting .................................................. 10 Specifications........................................................ 11 Keep the unit as far away as possible from Limited Warranty................................................... 12 electromagnetic equipment (such as microwave ovens, TVs, video games, radio transmitters, -If you see this symbol- high-voltage lines etc.). ≥ Do not use the camera near cell phones because Information -

YONGNUO, MEDIAEDGE, and Venus Optics Join the Micro Four Thirds System Standard Group

February 20, 2020 YONGNUO, MEDIAEDGE, and Venus Optics Join the Micro Four Thirds System Standard Group Olympus Corporation and Panasonic Corporation jointly announced the Micro Four Thirds System standard in 2008 and have since been working together to promote the standard. We are pleased to announce that three more companies have recently declared their support for the Micro Four Thirds System standard and will be introducing products compliant with the standard. The following companies are joining the Micro Four Thirds System standard group: YONGNUO which develops, produces and sells digital camera switching lenses, performance lighting, video lighting, etc., MEDIAEDGE Corporation, which has been an advocate of video streaming and display system concepts for over 17 years, aiming to produce products that inspire customers, and Venus Optics, the company behind the development and production of LAOWA brand, which produces incredibly practical, cost-effective, and unique products. The possibilities unique to a joint standard are sure to push the enjoyment of imaging ever further. As the company responsible for initiating both the Four Thirds System and the Micro Four Thirds System standards, Olympus will continue to develop and enhance the product line-up to meet the diverse needs of our customers. About YONGNUO YONGNUO regards "reflecting the beauty of the world and writing into a happy life" as the mission of the company. In the field of image in the information society, YONGNUO is a company that integrates the strength of all employees to develop and produce excellent products and make contributions to the society. YONGNUO Website: http://www.hkyongnuo.com/e-index.php About MEDIAEDGE Corporation MEDIAEDGE Corporation has been involved in developing imaging systems for over 17 years, with - 1 - a track record of sales to various industries and business categories, the support of many loyal customers, and a long history in Japan and around the world.