This Is a Self-Archived Version of an Original Article. This Version May Differ from the Original in Pagination and Typographic Details

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

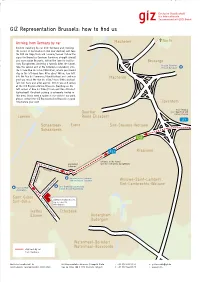

Brussels Aterloose Charleroisestwg

E40 B R20 . Leuvensesteenweg Ninoofsestwg acqmainlaan J D E40 E. oningsstr K Wetstraat E19 an C ark v Belliardstraat Anspachlaan P Brussel Jubelpark Troonstraat Waterloolaan Veeartsenstraat Louizalaan W R20 aversestwg. T Kroonlaan T. V erhaegenstr Livornostraat . W Louizalaan Brussels aterloose Charleroisestwg. steenweg Gen. Louizalaan 99 Avenue Louise Jacqueslaan 1050 Brussels Alsembergsesteenweg Parking: Brugmannlaan Livornostraat 14 Rue de Livourne A 1050 Brussels E19 +32 2 543 31 00 A From Mons/Bergen, Halle or Charleroi D From Leuven or Liège (Brussels South Airport) • Driving from Leuven on the E40 motorway, go straight ahead • Driving from Mons on the E19 motorway, take exit 18 of the towards Brussels, follow the signs for Centre / Institutions Brussels Ring, in the direction of Drogenbos / Uccle. européennes, take the tunnel, and go straight ahead until you • Continue straight ahead for about 4.5 km, following the tramway reach the Schuman roundabout. (the name of the road changes : Rue Prolongée de Stalle, Rue de • Take the 2nd road on the right to Rue de la Loi. Stalle, Avenue Brugmann, Chaussée de Charleroi). • Continue straight on until you cross the Small Ring / Boulevard du • About 250 metres before Place Stéphanie there are traffic lights: at Régent. Turn left and take the small Ring (tunnels). this crossing, turn right into Rue Berckmans. At the next crossing, • See E turn right into Rue de Livourne. • The entrance to the car park is at number 14, 25 m on the left. E Continue • Follow the tunnels and drive towards La Cambre / Ter Kameren B From Ghent (to the right) in the tunnel just after the Louise exit. -

Administrative Information

51st meeting of the Implementation Group Brussels, 6th to 8th September 2021 ADMINISTRATIVE INFORMATION Dear Ladies and Gentlemen, Welcome to the 51st meeting of the Implementation Group, which will be organised by the European Security and Defence College (ESDC); the first one after the break out of the pandemic, which will take place in Brussels in a purely residential format. GENERAL INFORMATION Upon arrival you will be provided with a meeting folder and the final meeting programme. At the end of the meeting you will be provided with an official Confirmation of stay (for those who need it). The presentations will be available in pdf-format on http://emilyo.eu/node/1191 by the end of the 52nd IG meeting in Sofia. As far as the dress code is concerned, we recommend suit and tie. Active members of the armed forces and the police aren’t obliged to wear their uniforms. The can follow the general rule (suit and tie). PROGRAMME The meeting will be organised in a purely residential format respecting all the COVID-19 restrictions in force. This means that no VTC option is available. Meeting starts on Monday, 6th September 2021 at 16.00 and concludes on Wednesday, 8th September 2021 at 12.30. Tuesday session starts at 09.00 am and concludes at 18.00. Coffee breaks: up to the group Lunch breaks: 1 ½ hours. ACCOMMODATION ESDC doesn’t have any arrangements with hotels in Brussels and we don’t recommend anyone. However, you can find below a list of hotels used by our meetings / courses participants in the past: Silken Berlaymont Hotel First Euroflat Hotel (4 stars) just behind Berlaymont building Hotel Chelton (3 stars, close to ESDC, on Rue Veronesse, the closest) Holiday Inn Brussels Schuman (3 stars, on rue Breydel, close to metro Schuman). -

Meeting of the Parties to the Agreement on the Establishment of the NDPHS Secretariat (MP) Fifth Meeting Brussels, Belgium 15 April 2015

Meeting of the Parties to the Agreement on the Establishment of the NDPHS Secretariat (MP) Fifth Meeting Brussels, Belgium 15 April 2015 Reference MP 5/Info1 Title Practical information for participants Submitted by Secretariat CONTACT INFORMATION NDPHS Secretariat Host, DG SANTE Ms Silvija Juscenko Mr Eddy Parijs Senior Adviser Policy Officer NDPHS Secretariat Rue Froissart 101 Phone: +46 760 219544 B-1040 Brussels [email protected] Belgium Phone: +32 22960444 E-mail: [email protected] MEETING VENUE Berlaymont building Rue de la Loi 200 Schuman Roundabout Meeting room Jean Rey (JREY), 1st floor The location of the meeting venue is shown on the map attached to this document as Annex 1. CONFIRMATION OF PARTICIPATION Kindly confirm your participation in the meeting by 7 April 2015 by using the on-line registration form, which is available on the NDPHS website at: http://www.ndphs.org/?mtgs,mp_5__brussels. ACCOMMODATION Participants are kindly asked to make their own hotel reservations. MEALS DURING THE MEETING Refreshments during the meeting will be offered free of charge by the Host. A canteen is available at the meeting venue for those participants who would like to have lunch at their own expense. MP_5-Info_1__Practical_information_for_participants.docx 1 TRAVEL INFORMATION From Brussels International Airport to the Schuman (European Commission) area: • Taxi (approx. € 35). Depending on the traffic, the travel time is 30-50 minutes. nd • Train to the Central Station (€ 8.50 one way, 2 class) and then metro (€ 2.00). • Express bus Line 12 and Line 21 (€ 4.00 one way if bought in advance and € 6.00 on- board). -

Sales Guide 2019 English Version © M

EN Sales Guide 2019 English version © M. Vanhulst The visit.brussels online sales guide is accessible to all, but is first and foremost aimed at professionals from the travel industry, namely tour operators, travel agents, coach companies and group organisers. It provides a complete overview of all activities and attractions in our city. These are then divided into specific themes which best represent Brussels, e.g. Art Nouveau, comics, heritage, etc. Each activity or attraction is explained in a file containing valuable information such as rates, contact details, languages in which the activity or attraction is provided, and much more. These files will allow travel professionals to take immediate action, should they wish to suggest an activity or attraction to their clients. The entire purpose of the sales guide is to advertise the tremendous potential of Brussels and boost creativity with travel professionals in order for them to perk up, enhance or change their offer whilst making them and their clients eager to discover and get a better idea of the city. Equally important, the sales guide limits research and hence lightens the workload considerably. In addition, the visit.brussels online sales guide obviously contains information on upcoming events, accommodation providers, coach parking details, visit.brussels contact information and other relevant data. We trust this unique tool will benefit all travel professionals worldwide and encourage them to choose Brussels as their preferred destination. Rest assured that we will keep on -

Room Booking Form

Holiday Inn Brussels-Schuman Rue Breydelstraat 20-24 - 1040 Brussels - Belgium E-mail: [email protected] Web: www.holidayinn.com/brusselschuman Tel: +32 (0) 2 280 40 00 Fax: +32 (0) 2 282 10 70 Room booking form Rooms available for : Akademis Österreichs Energie Between the following date: 30/11 – 02/12/2014 Deadline 16/11/2014 Complete & return it to [email protected] Nam e Telephone Email address Arrival Departure Nr. of nights Nr. of rooms Nr. of people / children Credit card number with expiry date to guarantee of the room Price standard single room € 149 per night Price business single room € 179 per night City tax €4.5 per room, per night Price breakfast Included Price Wi -Fi €9 for standard room, Free for business room Rooms can be cancelled free of charge until 5 days before arrival. In case of cancelation after 25/11 or no show, the entire stay will be charged. Holiday Inn Brussels-Schuman Rue Breydelstraat 20-24 - 1040 Brussels - Belgium E-mail: [email protected] Web: www.holidayinn.com/brusselschuman Tel: +32 (0) 2 280 4000 Fax: +32 (0) 2 282 1070 Hungry? Try our new and improved menu! You can make a reservation in our restaurant upon check-in or call +32 2 280 40 00! Welcome at Pablo’s Brasserie Open Monday-Sunday Non stop from 11 AM till 11 PM Holiday Inn Brussels-Schuman Rue Breydelstraat 20-24 - 1040 Brussels - Belgium E-mail: [email protected] Web: www.holidayinn.com/brusselschuman Tel: +32 (0) 2 280 40 00 Fax: +32 (0) 2 282 10 70 Stay in the heart of the EU district at the intimate Holiday Inn Brussels-Schuman hotel. -

(Salle Jean Rey). the Berlaymont Is Clearly Visible from the Schuman Roundabout

PRACTICAL ARRANGEMENTS THE CONFERENCE VENUE (I.E. THE BERLAYMONT), THE HOTEL (I.E. THE SILKEN BERLAYMONT) AND THE RESTAURANT FOR FRIDAY NIGHT (I.E. L'ATELIER) ARE ALL LOCATED CLOSE TO EACH OTHER IN THE SCHUMAN AREA OF BRUSSELS AND WITHIN 5 MINUTES WALKING DISTANCE OF THE SCHUMAN ROUNDABOUT (ROND POINT SCHUMAN / SCHUMANPLEIN) CONFERENCE VENUE : The conference takes place in the European Commission's Berlaymont building (Salle Jean Rey). The Berlaymont is clearly visible from the Schuman roundabout. On the first day of the conference, please bring a copy of the invitation e-mail sent to you, as well as a passport or identity card, in order to meet the security requirements needed to gain entry to the Berlaymont building. Once inside the building, someone will be waiting for you with directions as to how to get to the Jean Rey meeting room where the conference will take place. ADDRESS : 200 Rue de la Loi / Wetstraat – 1000 Brussels HOW TO GET TO THE CONFERENCE VENUE 1 1. From Brussels-National Airport: . Licensed taxis are available outside the Arrivals hall. The fare should cost around €40-€45. Airport line: take the No.12 bus (or No. 21 after 20:00 or on weekends) to “Schuman”, a two-minute walk from the venue. It leaves three times an hour from the Bus Station on the level below Arrivals. The journey should take around 30 minutes and cost €5 if the ticket is bought on board (€3 if bought in advance). Trains leave the station on Level -1 of the airport four times an hour. -

View Annual Report

annual financial report 2009. protection. Since the beginning of time, the tree has been a source of protection. Whether providing shelter and home to early man, or as a central pillar in complicated ecosystems, the simple tree is a symbol of strength and security. Adapting constantly to its surroundings, it is a natural example of reliability, longevity and endurance.. It is fascinating that just as early man sought shelter and protection from a tree, modern man today is doing his best to protect them... ...now we all know that trees play a fundamental role in the protection of our planet. Cofinimmo is the foremost listed Belgian real estate company specialising in The buildings represent a total area of 1,695,629m² and a fair value rental property. The company benefits from the fiscal Sicafi regime in Belgium of €3,040.74 million. and the fiscal SIIC regime in France. Cofinimmo is an independent company, which manages its properties and Its core investment segments are office property and care homes representing clients-tenants in-house. 58.4% and 26.4% respectively of the Group’s total portfolio. It also comprises the It is listed on Euronext Brussels, where it is included in the BEL20 index, and Pubstone portfolio (12.8%), a real estate partnership concluded with AB InBev. Euronext Paris. Its shareholders are mainly private individuals and institutional The properties are mainly located in Belgium (84.2%). The assets abroad investors from Belgium and abroad, looking for a moderate risk profile concern, on one hand, the investments in the nursing and care sector in France combined with a high dividend yield. -

WORKSHOP VENUE (Directions & Accommodation)

WORKSHOP VENUE (Directions & Accommodation) Network Security Assessment Days The iTesla project’s results presentation November 4th – 5th 2015, Brussels The sessions will take place in the Auditorium of the Liaison Agency Flanders-Europe (VLEVA), near the ENTSO-E premises and in the same building as CORESO Itinerary Liaison Agency Flanders-Europe (VLEVA) Avenue de Cortenbergh/ Kortenberglaan 71 Schuman Quarter 1000 Brussels From Brussels Central Station Take metro lines 5 (direction Hermann-Debroux) or 1 (direction Stokkel) and get off at “Schuman” (= 4th stop). Take exit “Wetstraat/ Rue de la Loi”, go to the Schuman roundabout and take Avenue the Cortenbergh/ Kortenberglaan. Our building is on the right hand side, number 71 (about 150 meters beyond the mosque). From Brussels Midi Take metro line 2 (direction Simonis) to Arts-Loi/ Kunst-Wet. Change to metro line 5 (Hermann- Debroux) or 1 (Stokkel) and get off at “Schuman” (= 4th stop). Take exit “Wetstraat/ Rue de la Loi”, go to the Schuman roundabout and take the Avenue the Cortenbergh/ Kortenberglaan. Our building is on the right hand side, number 71 (about 150 meters beyond the mosque). From Brussels National Airport By train: Take the train (the train station is located underground) towards "Bruxelles-Gare Centrale" (Brussels Central Station). (+/- 15 minutes). Then take the metro Line 1a or 1b towards Schuman Station (Direction Stockel or Herrmann Debroux). (+/- 5 minutes) By Bus: Take the bus line 12 (Airport line) (the bus station is located on ground floor) towards Schuman bus stop (Direction Brussels-City). Total journey from Airport VLEVA: +/- 30 minutes. Train and metro facilities Travelling schemes, practical info, stations list, tickets etc. -

GIZ Representation Brussels: How to Find Us

GIZ Representation Brussels: how to find us North Arriving from Germany by car Machelen Visitors travelling by car from Germany and crossing the border at Lichtenbusch (A4 near Aachen) will take the E40 via Liège / Luik and Louvain / Leuven. Follow the signs for Bruxelles Centrum (continue straight ahead) and once inside Brussels, follow the lane for Institu- Brucargo tions Européennes (entering a tunnel). After the tunnel, Brussel Zaventem take the second exit at the Schuman roundabout, onto Brussel Nationaal the 4-lane Rue de la Loi / Wetstraat, where you should stay in the left-hand lane. After about 500 m, turn left into the Rue du Commerce / Handelsstraat and continue Machelen until you reach the Rue du Trône / Troon (fifth junction). Turn left here and after approx. 300 m you will arrive at the GIZ Representation Brussels (building on the left corner of Rue du Trône / Troon and Rue d’Idalie / Idaliestraat). On-street parking is extremely limited in this area. If you need a space in our visitors’ car park, please contact the GIZ Representation Brussels in good time before your visit. Zaventem from Germany via Liège / Luik and Quartier Louvain / Leuven Laeken Reine Elisabeth A 3 Schaerbeek Evere Sint-Stevens-Woluwe Schaarbeek E 40 N 23 Kraainem entrance of the tunnel roundabout lane for Institutions Européennes Rue de la Loi Schuman Wetstraat Gare Bruxelles-Schuman Rue du Commerce Station Brussel-Schuman Woluwe-Saint-Lambert Handelsstraat Sint-Lambrechts-Woluwe Gare Bruxelles-Luxembourg Gare du Midi Station Brussel-Luxemburg Zuidstation -

Handbook on CSDP

Handbook on CSDP The Common Security and Defence Policy of the European Union Volume I 4th edition HANDBOOK ON CSDP THE COMMON SECURITY AND DEFENCE POLICY OF THE EUROPEAN UNION Fourth edition edited by Jochen Rehrl with forewords by Josep Borrell High Representative of the Union for Foreign Affairs and Security Policy and Vice President of the European Commission Klaudia Tanner Federal Minister of Defence of the Republic of Austria This document has been produced with the financial assistance of the European Union. Disclaimer: Any views or opinions presented in this handbook are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of the European Union and the Federal Ministry of Defence of the Republic of Austria. Publication of the Federal Ministry of Defence of the Republic of Austria Editor: Jochen Rehrl Idea and concept: Jochen Rehrl Layout: Axel Scala, Andreas Penkler, Armed Forces Printing Centre, Vienna Published by: Directorate for Security Policy of the Federal Ministry of Defence of the Republic of Austria Picture credits for the front page: EUTM Mail, EUMM Georgia, EULEX Kosovo, Dati Bendo, Johan Lundahl Printed and bound by: Armed Forces Printing Centre, Vienna/Austria, 2021 21-00677 © Federal Ministry of Defence of the Republic of Austria and Jochen Rehrl ISBN: 978-3-902275-51-6 Printed according to the Austrian Ecolabel for printed matter, UW-Nr. 943 CONTENTS 1 COMMON SECURITY AND DEFENCE POLICY 1.1. History and Development of the CSDP (Gustav Lindstrom) ....................................... 16 1.2. The EU Global Strategy ................................................................................................ 21 Graphic: Peace and Security ............................................................................................ 26 Factsheet: European Defence Action Plan ........................................................................ -

Bruxelles 6, Rond-Point Schuman Intro

BRUXELLES 6, ROND-POINT SCHUMAN INTRO » Europe will not be made all at once, or according to a single plan. It will be built through concrete achievements, which first create a de facto solidarity. « Robert Schuman INTRO INTRO Dr. jur. Robert Schuman *29 June 1886 in Clausen, a district of the city of Luxembourg † 4 September 1963 in Chazelles, near Metz, France As the French Foreign Minister (1948 –1952) and the first President of the European Parliament, he campaigned for reconciliation between Germany and France. He is known as the “Father of Europe” as a result of his work. He was the driving force behind the establishment of the first European Community (ECSC). 4 SCHUMAN 6 » THE IDEA SCHUMAN 6 THE VISIONARY PLACE The Schuman Roundabout is named after the former French Foreign Minister, Robert Schuman. When he laid the foundations for the European Coal and Steel Community with his speech on 9 May 1950, he already had a bigger vision in mind: a dream of Europe. Today, this dream has become a reality and Brussels is the centre of the European Community. At the heart of the Euro- pean District, with many European institutions in immediate proximity, Schuman 6 offers you precisely what the founding fathers of the European Union stood for: unique perspectives. A high-class location, outstandingly situated within Brussels and boasting excellent transport connections. A location that sets standards. A place for your visions to become reality. Welcome to Schuman 6. SCHUMAN 6 SCHUMAN 6 INTRO UN LIEU VISIONNAIRE DE VISIONAIRE PLAATS Le rond-point Schuman emprunte son nom à l’ancien ministre Het Schumanplein dankt zijn naam aan de toenmalige, Franse français des Affaires Etrangères Robert Schuman. -

Metropolis Your Office

A WILLEMEN REAL ESTATE PROJECT MAGNIFICANT YOUR OFFICE VIEWS METROPOLIS AT THE HEART OF EUROPE YOUR OFFICE AT THE HEART OF EUROPE Welcome in the European Quarter of Brussels! the European Quarter, within walking distance The vibrant Quarter, located in the east of of Parc Léopold and Parc du Cinquantenaire, the Brussels city centre, is characterised by an Willemen Real Estate is developing the mixed- interesting mix of contemporary governmental use project ‘Metropolis’. buildings, such as the European Parliament, as well as an abundance of city parcs. The Place This new construction project, built on the du Luxembourg, just a kilometer away, offers a domain of the former Irish embassy, consists varied choice of bustling and cosy restaurants of 47 apartments, commercial spaces on the and the streets around Metropolis are filled ground floor and offices from the first to the third with shops, gourmet eateries, museums floor. The entrance on Rue Froissart provides and public transport. access to the two-storied underground car park. In the heart of The entrance hall and vertical circulation of the offices to the underground garage are separate from the entrance hall of the apartments. The parking spaces and communal bicycle storage spaces are located in the underground garage. 47APARTMENTS STUDIOS 1, 2, 3 BEDROOMS 2.317 M2 OFFICE SPACES Location: Architect: Development: Froissartstraat 79-93 & ADE sprl Willemen Real Estate COMMERCIAL Belliardstraat 222-228 Chaussée de la Hulpe 181/6 Boerenkrijgstraat 133 GROUND FLOOR 1000 Brussel 1170 Bruxelles 2800 Mechelen WWW.METROPOLIS-BRUSSELS.BE LOCATION SURFACES ARCHITECTURE Centrally located a few steps from the Schuman roundabout, it is easily accessible from all cor- The architecture of the Metropolis project creates an iconic stamp on the bustling and vibrant OFFICE PARKING ners of the country via the E19, A12, E429 and E411.