Utilization of Douglas-Fir Bark

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Pdf, 11.42 Mb

FOTO: SAMUEL PORTELA INSTITUTIONS PARTICIPATING IN THE OVERALL COORDINATION VALIDATION WORKSHOP TECHNICAL TEAM AD2M CAATINGA ASSOCIATION ADECE Daniel Fernandes ASSOCIAÇÃO CAATINGA Kelly Cristina Luana Ribeiro CAPOL Lucas Moura CARNAÚBA DO BRASIL Marília Nascimento CEROEPER Sandino Silva COETRAE Samuel Portela EMBRAPA SDA FAEC Marcílio Melo FETRAECE FIEC EMBRAPA Vicente de Paula Queiroga FONCEPI GIZ FAEC HARIBO Ivonisa Holanda INSS Ossian Dias Jucileide Nogueira MEMORIAL DA CARNAÚBA MAPA GIZ MMA Octávio Nogueira MPT-CE Louisa Lösing MPT-PI INSS MPT-RN Ruiter Lima NATURA Irisa Viana NATURAL WAX Rafael Ferreira NRSC NUTEC PONTES INDÚSTRIA DE CERA Alessandra Nascimento Souza de Oliveira RODOLFO G. MORAES - ROGUIMO Iêda Nadja Silva Montenegro SDA SEJUS MMA Daniel Barbosa SINDCARNAÚBA SRTE-CE UEBT SRTE-RN Ronaldo Freitas STDS Rodrigo de Próspero UEBT ESPECIALISTAS CONVIDADOS UECE Carolina Serra INVITED EXPERTS Jessika Sampaio GRAPHIC DESIGN AND LAYOUT Luana Ribeiro e Kelly Cristina FOTO: RENATO STOCKLER ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS This handbook was developed through a partnership between the Ministry of Agriculture, Livestock and Food Supply (MAPA), the Deutsche Gesellschaft für Internationale Zusammenarbeit (GIZ) and the Associação Caatinga, within the framework of the Private Sector Action for Biodiversity Project, as part of the International Climate Initiative (IKI). The German Federal Ministry for the Environment, Nature Conservation and Nuclear Safety (BMU) supports this initiative based on a decision taken by the Bundestag. Acronyms ABNT - Brazilian -

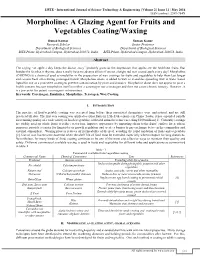

Morpholine: a Glazing Agent for Fruits and Vegetables Coating/Waxing (IJSTE/ Volume 2 / Issue 11 / 119) with Glazing Agent

IJSTE - International Journal of Science Technology & Engineering | Volume 2 | Issue 11 | May 2016 ISSN (online): 2349-784X Morpholine: A Glazing Agent for Fruits and Vegetables Coating/Waxing Rupak Kumar Suman Kapur Research Scholar Senior Professor Department of Biological Sciences Department of Biological Sciences BITS-Pilani, Hyderabad Campus, Hyderabad-500078, India BITS-Pilani, Hyderabad Campus, Hyderabad-500078, India Abstract The saying “an apple a day keeps the doctor away” probably gives us the impression that apples are the healthiest fruits. But besides the fact that it rhymes, does it really have no adverse effects if we eat a bright red wax coated apple every day? Morpholine (C4H9NO) is a chemical used as emulsifier in the preparation of wax coatings for fruits and vegetables to help them last longer and remain fresh even during prolonged transit. Morpholine oleate is added to wax as it enables spreading wax in water based liquid for use as a protective coating to prevent contamination by pests and diseases. Morpholine alone does not appear to pose a health concern because morpholine itself is neither a carcinogen nor a teratogen and does not cause chronic toxicity. However, it is a precursor for potent carcinogenic nitrosamines. Keywords: Carcinogen, Emulsifier, Morpholine, Teratogen, Wax Coating ________________________________________________________________________________________________________ I. INTRODUCTION The practice of fruit/vegetable coating was accepted long before their associated chemistries were understood, and are still practiced till date. The first wax coating was applied to citrus fruits in 12th-13th centuries in China. Today, it has expanded rapidly for retaining quality of a wide variety of foods/vegetables, with total annual revenue exceeding $100 million [1]. -

(Piper Nigrum L.) Products Based on LC-MS/MS Analysis

molecules Article Nontargeted Metabolomics for Phenolic and Polyhydroxy Compounds Profile of Pepper (Piper nigrum L.) Products Based on LC-MS/MS Analysis Fenglin Gu 1,2,3,*, Guiping Wu 1,2,3, Yiming Fang 1,2,3 and Hongying Zhu 1,2,3,* 1 Spice and Beverage Research Institute, Chinese Academy of Tropical Agricultural Sciences, Wanning 571533, China; [email protected] (G.W.); [email protected] (Y.F.) 2 National Center of Important Tropical Crops Engineering and Technology Research, Wanning 571533, China 3 Key Laboratory of Genetic Resources Utilization of Spice and Beverage Crops, Ministry of Agriculture, Wanning 571533, China * Correspondence: [email protected] (F.G.); [email protected] (H.Z.); Tel.: +86-898-6255-3687 (F.G.); +86-898-6255-6090 (H.Z.); Fax: +86-898-6256-1083 (F.G. & H.Z.) Received: 16 July 2018; Accepted: 7 August 2018; Published: 9 August 2018 Abstract: In the present study, nontargeted metabolomics was used to screen the phenolic and polyhydroxy compounds in pepper products. A total of 186 phenolic and polyhydroxy compounds, including anthocyanins, proanthocyanidins, catechin derivatives, flavanones, flavones, flavonols, isoflavones and 3-O-p-coumaroyl quinic acid O-hexoside, quinic acid (polyhydroxy compounds), etc. For the selected 50 types of phenolic compound, except malvidin 3,5-diglucoside (malvin), 0 L-epicatechin and 4 -hydroxy-5,7-dimethoxyflavanone, other compound contents were present in high contents in freeze-dried pepper berries, and pinocembrin was relatively abundant in two kinds of pepper products. The score plots of principal component analysis indicated that the pepper samples can be classified into four groups on the basis of the type pepper processing. -

How to Make an Electret the Device That Permanently Maintains an Electric Charge by C

How to Make an Electret the Device That Permanently Maintains an Electric Charge by C. L. Strong Scientific America, November, 1960 Danger Level 4: (POSSIBLY LETHAL!!) Alternative Science Resources World Clock Synthesis Home --------------------- THE HISTORY OF SCIENCE IS A TREASURE house for the amateur experimenter. For example, many devices invented by early workers in electricity and magnetism attract little attention today because they have no practical application, yet these devices remain fascinating in themselves. Consider the so-called electret. This device is a small cake of specially prepared wax that has the property of permanently maintaining an electric field; it is the electrical analogue of a permanent magnet. No one knows in precise detail how an electret works, nor does it presently have a significant task to perform. George O. Smith, an electronics specialist of Rumson, N.J., points out, however, that this is no obstacle to the enjoyment of the electret by the amateur. Moreover, the amateur with access to a source of high-voltage current can make an electret at virtually no cost. "For more than 2,000 years," writes Smith, "it was suspected that the magnetic attraction of the lodestone and the electrostatic attraction of the electrophorus were different manifestations of the same phenomenon. This suspicion persisted from the time of Thales of Miletus (600 B.C.) to that of William Gilbert (A.D. 1600). After the publication of Gilbert's treatise De Magnete, the suspicion graduated into a theory that was supported by many experiments conducted to show that for every magnetic effect there was an electric analogue, and vice versa. -

Original Contributions to Flavonoid Biochemistry

433 REVIEW / SYNTHÈSE A forty-year journey in plant research: original contributions to flavonoid biochemistry Ragai K. Ibrahim Abstract: This review highlights original contributions by the author to the field of flavonoid biochemistry during his research career of more than four decades. These include elucidation of novel aspects of some of the common enzy- matic reactions involved in the later steps of flavonoid biosynthesis, with emphasis on methyltransferases, glucosyltransferases, sulfotransferases, and an oxoglutarate-dependent dioxygenase, as well as cloning, and inferences about phylogenetic relationships, of the genes encoding some of these enzymes. The three-dimensional structure of a flavonol O-methyltransferase was studied through homology-based modeling, using a caffeic acid O-methyltransferase as a template, to explain their strict substrate preferences. In addition, the biological significance of enzymatic prenylation of isoflavones, as well as their role as phytoanticipins and inducers of nodulation genes, are emphasized. Finally, the potential application of knowledge about the genes encoding these enzyme reactions is discussed in terms of improving plant productivity and survival, modification of flavonoid profiles, and the search for new compounds with pharmaceutical and (or) nutraceutical value. Key words: flavonoid enzymology, metabolite localization, gene cloning, 3-D structure, phylogeny. Résumé : Dans cette revue, l’auteur fait état de ses contributions originales à la recherche sur la biochimie des flavo- noïdes, au cours des 40 années de sa carrière de recherche. Celles-ci incluent la mise à jour de nouveaux aspects de certaines des réactions enzymatiques impliquées dans les dernières étapes de la biosynthèse des flavonoïdes, avec un accent sur les méthyltransférases, glycotransférases, sulfotransférases et une dioxygénase dépendante de l’oxoglutarate, ainsi que sur le clonage, incluant leurs relations phylogénétiques, des gènes codant pour certaines de ces enzymes. -

Non-Wood Forest Products

Non-farm income wo from non- od forest prod ucts FAO Diversification booklet 12 FAO Diversification Diversification booklet number 12 Non-farm income wo from non- od forest products Elaine Marshall and Cherukat Chandrasekharan Rural Infrastructure and Agro-Industries Division Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations Rome 2009 The views expressed in this publication are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. The designations employed and the presentation of material in this information product do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO) concerning the legal or development status of any country, territory, city or area or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. The mention of specific companies or products of manufacturers, whether or not these have been patented, does not imply that these have been endorsed or recommended by FAO in preference to others of a similar nature that are not mentioned. All rights reserved. Reproduction and dissemination of material in this information product for educational or other non-commercial purposes are authorized without any prior written permission from the copyright holders provided the source is fully acknowledged. Reproduction of material in this information product for resale or other commercial purposes is prohibited without written permission of the copyright holders. -

Agency Approvals LIQUIDS, SOLUTIONS & SUSPENSIONS

LT_3722_v8_MRO.qxp 11/5/07 3:02 PM Page 48 Fluid Compatibility Chart for metal threaded fittings sealed with Loctite® Sealants Agency Approvals LIQUIDS, SOLUTIONS & SUSPENSIONS ● ● ● ● ● NSF International Loctite® 554™ Thread Sealant, Refrigerant Sealant Loctite® Instant Gasket LEGEND: Antioxidant Gasoline ...................... Cellulose Xanthate ........................ Dust-Flue (Dry) .............................. GRS Latex ..................................... Maleic Anhydride .......................... Loctite® QuickStix™ 561™ PST® Pipe Sealant Loctite® Maintain® Lubricant Penetrant ● All Loctite® Anaerobic Sealants Aqua Regia .................................... ✖ Cement Dry/Air Blown ................... ● Dye Liquors.................................... ● Gum Paste .................................... ● Manganese Chloride ...................... ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● LEGEND: = Non-Food Grade = Standard 51 = Standard 61 Loctite® 564™ Thread Sealant, General Purpose Loctite® Maxi-Coat™, Aerosol are Compatible Including # Argon ............................................ Cement Grout ................................ Gum Turpentine ............................. Manganese Sulfate ........................ ● ● ● ● ● Loctite® 565™ PST® Thread Sealant, Controlled Strength Loctite® Maxi-Coat™ Liquid 242®, 243™, 542™, 545™, Armeen § ...................................... Cement Slurry ............................... Emery-Slurry ................................. Gypsum ........................................ Melamine Resin ........................... -

Flavonoids and Related Compounds As Anti-Allergic Substances

Allergology International. 2007;56:113-123 ! DOI: 10.2332 allergolint.R-06-135 REVIEW ARTICLE Flavonoids and Related Compounds as Anti-Allergic Substances Mari Kawai1,ToruHirano1,ShinjiHiga2, Junsuke Arimitsu1, Michiru Maruta1, Yusuke Kuwahara1, Tomoharu Ohkawara1, Keisuke Hagihara1, Tomoki Yamadori1, Yoshihito Shima1,AtsushiOgata1, Ichiro Kawase1 and Toshio Tanaka1 ABSTRACT The prevalence of allergic diseases has increased all over the world during the last two decades. Dietary change is considered to be one of the environmental factors that cause this increase and worsen allergic symp- toms. If this is the case, an appropriate intake of foods or beverages with anti-allergic activities is expected to prevent the onset of allergic diseases and ameliorate allergic symptoms. Flavonoids, ubiquitously present in vegetables, fruits or teas possess anti-allergic activities. Flavonoids inhibit histamine release, synthesis of IL-4 and IL-13 and CD40 ligand expression by basophils. Analyses of structure-activity relationships of 45 flavones, flavonols and their related compounds showed that luteolin, ayanin, apigenin and fisetin were the strongest in- hibitors of IL-4 production with an IC50 value of 2―5 μM and determined a fundamental structure for the inhibi- tory activity. The inhibitory activity of flavonoids on IL-4 and CD40 ligand expression was possibly mediated through their inhibitory action on activation of nuclear factors of activated T cells and AP-1. Administration of flavonoids into atopic dermatitis-prone mice showed a preventative and ameliorative effect. Recent epidemi- ological studies reported that a low incidence of asthma was significantly observed in a population with a high intake of flavonoids. Thus, this evidence will be helpful for the development of low molecular compounds for al- lergic diseases and it is expected that a dietary menu including an appropriate intake of flavonoids may provide a form of complementary and alternative medicine and a preventative strategy for allergic diseases. -

Medicinally Important Aromatic Plants with Radioprotective Activity

Review Medicinally important aromatic plants with radioprotective activity Ravindra M Samarth*,1,2, Meenakshi Samarth3 & Yoshihisa Matsumoto4 1Department of Research, Bhopal Memorial Hospital & Research Centre, Department of Health Research, Government of India, Raisen Bypass Road, Bhopal 462038, India 2ICMR-National Institute for Research in Environmental Health, Kamla Nehru Hospital Building, GMC Campus, Bhopal 462001, India 3Faculty of Science, RKDF University, Airport Bypass Road, Gandhi Nagar, Bhopal 462033, India 4Tokyo Institute of Technology, Institute of Innovative Research, Laboratory for Advanced Nuclear Energy, N1–30 2–12–1 Ookayama, Meguro-ku, Tokyo 152–8550, Japan * Author for correspondence: [email protected] Aromatic plants are often used as natural medicines because of their remedial and inherent pharmaco- logical properties. Looking into natural resources, particularly products of plant origin, has become an exciting area of research in drug discovery and development. Aromatic plants are mainly exploited for essential oil extraction for applications in industries, for example, in cosmetics, flavoring and fragrance, spices, pesticides, repellents and herbal beverages. Although several medicinal plants have been studied to treat various conventional ailments only a handful studies are available on aromatic plants, especially for radioprotection. Many plant extracts have been reported to contain antioxidants that scavenge free radicals produced due to radiation exposure, thus imparting radioprotective efficacy. The present review focuses on a subset of medicinally important aromatic plants with radioprotective activity. Lay abstract: Aromatic plants have been used as natural medicines since prehistoric times. They are cur- rently mainly utilized for essential oil extraction and are widely used in cosmetics, flavoring and fragrance, spices, pesticides, repellent and herbal beverages. -

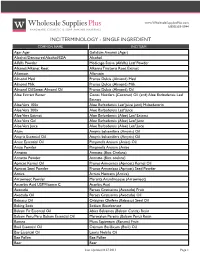

INCI Terminology

www.WholesaleSuppliesPlus.com 1(800)359-0944 INCI TERMINOLOGY - SINGLE INGREDIENT COMMON NAME INCI TERM Agar Agar Gelidium Amansii (Agar) Alcohol/Denatured Alcohol/SDA Alcohol Alfalfa Powder Medicago Sativa (Alfalfa) Leaf Powder Alkanet/Alkanet Root Alkanna Tinctoria Root Extract Allantoin Allantoin Almond Meal Prunus Dulcis (Almond) Meal Almond Milk Prunus Dulcis (Almond) Milk Almond Oil/Sweet Almond Oil Prunus Dulcis (Almond) Oil Aloe Extract Butter Cocos Nucifera (Coconut) Oil (and) Aloe Barbadensis Leaf Extract Aloe Vera 100x Aloe Barbadensis Leaf Juice (and) Maltodextrin Aloe Vera 200x Aloe Barbadensis Leaf Juice Aloe Vera Extract Aloe Barbadensis (Aloe) Leaf Extract Aloe Vera Gel Aloe Barbadensis (Aloe) Leaf Juice Aloe Vera Juice Aloe Barbadensis (Aloe) Leaf Juice Alum Amyris balsamifera (Amyris) Oil Amyris Essential Oil Amyris balsamifera (Amyris) Oil Anise Essential Oil Pimpinella Anisum (Anise) Oil Anise Powder Pimpinella Anisum (Anise Annatto Annatto (Bixa Orelana) Annatto Powder Annatto (Bixa orelana) Apricot Kernel Oil Prunus Armeniaca (Apricot) Kernel Oil Apricot Seed Powder Prunus Armeniaca (Apricot) Seed Powder Arnica Arnica Montana (Arnica) Arrowroot Powder Maranta Arundinaceae (Arrowroot) Ascorbic Acid USP/Vitamin C Acorbic Acid Avocado Persea Gratissima (Avocado) Fruit Avocado Oil Persea Gratissima (Avocado) Oil Babassu Oil Orbignya Oleifera (Babassu) Seed Oil Baking Soda Sodium Bicarbonate Balsam Fir Essential Oil Abies Balsamea (Balsam Canda) Resin Balsam Peru/Peru Balsam Essential Oil Myroxylon Pereira (Balsam Peru) -

Developing Drug and Gene Therapies for Peroxisome Biogenesis Disorders of the Zellweger Spectrum

Developing drug and gene therapies for peroxisome biogenesis disorders of the Zellweger Spectrum Catherine Argyriou Department of Human Genetics McGill University, Montréal, Canada June 2018 A thesis submitted to McGill University in partial fulfillment of the requirements of the degree of Doctor of Philosophy © Catherine Argyriou 2018 ABSTRACT Zellweger spectrum disorder (ZSD) usually results from biallelic mutations in PEX genes required for peroxisome biogenesis. PEX1-G843D is a common hypomorphic allele associated with milder disease. We previously showed that fibroblasts from patients with a PEX1-G843D allele recovered peroxisome functions when cultured with the nonspecific chaperone betaine and flavonoid acacetin diacetate. To identify more effective flavonoids for preclinical trials, we compared 54 flavonoids using our cell-based peroxisomal assays. Diosmetin showed the most promising combination of potency and efficacy; co-treatments of diosmetin and betaine showed the most robust additive effects. This was confirmed by 5 independent assays in primary PEX1-G843D patient cells. Neither agent was active in PEX1 null cells. I propose that diosmetin acts as a pharmacological chaperone to improve stability, conformation, and function of PEX1/PEX6 exportomer complexes. All individuals with a PEX1-G843D allele develop a retinopathy that progresses to blindness. To investigate pathophysiology and identify endpoints for experimental trials, I used the knock-in mouse model for the equivalent human mutation, PEX1-G844D. I characterized the progression of retinopathy and found reduced cone cell function and number early in life with more gradual deterioration of rod cell function. Electron microscopy at later stage retinopathy showed disorganization of photoreceptor inner segments and enlarged mitochondria. As retino-cortical function was relatively well-preserved, I propose that the vision defect in the Pex1-G844D mouse is primarily at the retinal level. -

Zeitschrift Für Naturforschung / C / 33 (1978)

786 Notizen Stepwise Methylation of Quercetin by Cell-Free mitis) peel, (b) a callus tissue culture that was Extracts of Citrus Tissues initiated from calamondin seed, or (c) the root sys tem of 6-week old ‘Sunkist’ orange seedlings. All Gunter Brunet, Nabiel A. M. Saleh*, and Ragai K. procedures were conducted at 2 — 4 °C. Fresh or Ibrahim frozen tissues were mixed with sand and Polyclar Department of Biological Sciences, Concordia University, AT and homogenized with 0.1 M Tris-HCl buffer, Sir George Williams Campus, Montreal, Canada pH 7.8, containing 1 m M EDTA and 14 mM /?-mer- Z. Naturforschch. 33 e, 786 — 788 (1978) ; captoethanol. The supernatant obtained after cen received August 7, 1978 trifugation (20 min, 15000 xg) was fractionated O-Methylation, Quercetin, Citrus tissues with solid ammonium sulphate and the protein which precipitated between 30 — 70% saturation was The cell-free extracts of peel, root, or callus tissues of citrus catalyzed the stepwise O-methylation of quercetin to collected by centrifugation and dissolved in 50 mM rhamnetin, isorhamnetin and rhamnazin. Both rhamnetin of the same buffer. It was desalted on Sephadex and isorhamnetin were further methylated to rhamnazin and G-25 column and was directly used as the enzyme possibly to a trimethyl ether derivative of quercetin. The results seem to indicate the existence of both meta and source. para directing enzymes that are involved in the biosynthesis The standard assay mixture of O-methyltrans- of methylated flavonoids in citrus tissues. ferase consisted of 40 — 60 nmol of the phenolic substrate (dissolved in DMSO), 10 nmol S-[14CH3]- O-Methylated flavonoids are known for their wide adenosyl-L-methionine (New England Nuclear) con spread occurrence in the plant kingdom [1].