Future/Forward Day 2 2018

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

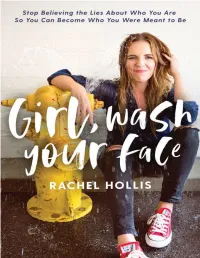

Girl, Wash Your Face

PRAISE FOR Girl, Wash Your Face “If Rachel Hollis tells you to wash your face, turn on that water! She is the mentor every woman needs, from new mommas to seasoned business women.” —ANNA TODD, New York Times and #1 internationally bestselling author of the After series “Rachel’s voice is the winning combination of an inspiring life coach and your very best (and funniest) friend. Shockingly honest and hilariously down to earth, Girl, Wash Your Face is a gift to women who want to flourish and live a courageously authentic life.” —MEGAN TAMTE, founder and co-CEO of Evereve “There aren’t enough women in leadership telling other women to GO FOR IT. We typically get the caregiver; we rarely get the boot camp instructor. Rachel lovingly but firmly tells us it is time to stop letting the tail wag the dog and get on with living our wild and precious lives. Girl, Wash Your Face is a dose of high-octane straight talk that will spit you out on the other end chasing down dreams you hung up long ago. Love this girl.” —JEN HATMAKER, New York Times bestselling author of For the Love and Of Mess and Moxie and happy online hostess to millions every week “In Rachel Hollis’s first nonfiction book, you will find she is less cheerleader and more life coach. This means readers won’t just walk away inspired, they will walk away with the right tools in hand to actually do their dreams. Dream doing is what Rachel is all about it. -

Simple Plan: Nuovo Tour E Nuovo Album Per La Band Pop Punk Di

LUNEDì 30 NOVEMBRE 2015 I Simple Plan, band di Montreal, arriva, finalmente in Italia, per due richiestissime date italiane. I Simple Plan saliranno sul palco dell'Estragon di Bologna il 1° marzo 2016 e su quello Simple Plan: nuovo tour e nuovo dell'Alcatraz di Milano il 2 marzo 2016 per quelli che saranno due show album per la band pop punk di spettacolari fatti da tutti i successi e le tracks del nuovo album "Taking Montreal! One For The Team" in uscita il 19 febbraio, per Warner Music Italy. Il Taking One For The Team Tour li riporta sui palchi di tutto il mondo. Il All'Estragon di Bologna il 1°marzo 2016 e loro quinto album, Taking One For The Team, è stato introdotto dal all'Alcatraz di Milano il 2 marzo 2016 super singoloI Don't Want To Go To Bed, nel cui video appare il bagnino più famoso di sempre: David Hasselhoff. LA REDAZIONE Special guest delle date italiane la band electronicore americana Ghost Town. Dopo una lunga serie di tour nel 2015, durante i quali sono arrivati anche a Treviso per l'Home Festival e a Roma come super guest dei Linkin Park, [email protected] la band si è messa a lavoro sul disco che promette sonorità cross over tra SPETTACOLINEWS.IT punk e pop, lyrics orecchiabili e la solita dose di positività che li ha sempre definiti come gruppo. Il gruppo si forma ufficialmente nel 1999 tra i banchi delle superiori, da una precedente band chiamata Reset. In un'intervista il chitarrista della band, Sébastien Lefebrve, ha dichiarato che dopo aver visto il film di Sam Raimi, 'A Simple Plan', ha pensato che fosse un nome perfetto per il gruppo. -

Model Police Work Safe to Play Outside? a Gutsy Strategy for Curbing Drug Crime Brings Community Together Page 8 Uncg Research

uncg research spring 2009 Research, Scholarship and Creative Activity MODEL POLICE WORK Safe to play outside? A gutsy strategy for curbing drug crime brings community together page 8 uncg research SPRING 2009 ° VOLUME 7 UNCG HAS A LONG HISTORY of outstanding achieve- ments in the behavioral sciences. As early as 1960 with UNCG Research is published by the creation of the PhD program in human development The Office of Research and family studies, quickly followed by the creation of the and Public/Private Sector Parnerships The University of North Carolina at Greensboro PhD program in psychology in 1970, UNCG’s behavioral PO Box 26170 Greensboro, NC 27402-6170 scientists have made impressive contributions to improv- 336.256.0426 ing health across the age span. We feature the work of Associate Provost for Research several in this issue of UNCG Research. and Public/Private Sector Partnerships Dr. Rosemary Wander Dr. Susan Calkins is an outstanding researcher. Her areas Administrative Assistant Debbie Freund of interest include social and emotional development in infancy and childhood, particularly as these developments Associate Vice Chancellor influence the emergence of aggressive behavior; the inter- for University Relations Helen Dennison Hebert ’97 MA face between emotion and cognition processes; and behavioral and biological approaches Editor to self-regulation. The focus of her research program has been to investigate these issues Beth English ’07 MALS in longitudinal samples of infants and young children. Her impressive body of work earned Art Director Lyda Adams Carpén ’88, ’95 MALS her UNCG’s Junior Research Excellence Award in 2000 and the Senior Research Excellence Photography Editor Chris English Award in 2008. -

MEMORIES, MATERS and the MYSTIQUE

MEMORIES, MATERS and the MYSTIQUE Submitted by VALARIE ROBINSON T.I.T.C. Bed. (LIB), BVA (HONS) STUDENT NO. 14314179 A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the MASTER OF VISUAL ART- by RESEARCH SUPERVISORS: NEIL FETTLING STEPHEN TURPIE School of Visual Arts and Design Faculty of Humanities and Social Science La Trobe University Bundoora, Victoria, 3086 Australia APRIL 2011 - 1 - ABSTRACT What was the contribution of the women who pioneered Mildura? The contribution and the endowment made by female pioneers to Mildura, is rarely recorded or acknowledged in historical documents and newspapers locally. Through reading about pioneer women in Australia, novels written between the 1880’s and 1920 and the role of women in history and prehistory, I researched why women, not just the pioneers, have become almost invisible in written records. The laws of the land and the customs of the Christian Church perpetuated the myth that women were the weaker sex and doomed them to life in the background supporting the hero, the masculine1. Male dominated perspective of feminine crafts such as embroidery and the fibre arts contributed to their exclusion from the mainstream of art and their rejection by art historians.2 With the rise of feminism in the 1890’s and more radically and profoundly in the 1970’s, the acceptance of the value of both women and women’s work, became possible.3 Art made a century ago by males and females confirmed the evidence of biased historical documentation in books and newspapers. However contemporary artists now use a variety of media without specific boundaries to express their concepts, emotions, criticisms on life. -

Jon Batiste and Stay Human's

WIN! A $3,695 BUCKS COUNTY/ZILDJIAN PACKAGE THE WORLD’S #1 DRUM MAGAZINE 6 WAYS TO PLAY SMOOTHER ROLLS BUILD YOUR OWN COCKTAIL KIT Jon Batiste and Stay Human’s Joe Saylor RUMMER M D A RN G E A Late-Night Deep Grooves Z D I O N E M • • T e h n i 40 e z W a YEARS g o a r Of Excellence l d M ’ s # m 1 u r D CLIFF ALMOND CAMILO, KRANTZ, AND BEYOND KEVIN MARCH APRIL 2016 ROBERT POLLARD’S GO-TO GUY HUGH GRUNDY AND HIS ZOMBIES “ODESSEY” 12 Modern Drummer June 2014 .350" .590" .610" .620" .610" .600" .590" “It is balanced, it is powerful. It is the .580" Wicked Piston!” Mike Mangini Dream Theater L. 16 3/4" • 42.55cm | D .580" • 1.47cm VHMMWP Mike Mangini’s new unique design starts out at .580” in the grip and UNIQUE TOP WEIGHTED DESIGN UNIQUE TOP increases slightly towards the middle of the stick until it reaches .620” and then tapers back down to an acorn tip. Mike’s reason for this design is so that the stick has a slightly added front weight for a solid, consistent “throw” and transient sound. With the extra length, you can adjust how much front weight you’re implementing by slightly moving your fulcrum .580" point up or down on the stick. You’ll also get a fat sounding rimshot crack from the added front weighted taper. Hickory. #SWITCHTOVATER See a full video of Mike explaining the Wicked Piston at vater.com remo_tamb-saylor_md-0416.pdf 1 12/18/15 11:43 AM 270 Centre Street | Holbrook, MA 02343 | 1.781.767.1877 | [email protected] VATER.COM C M Y K CM MY CY CMY .350" .590" .610" .620" .610" .600" .590" “It is balanced, it is powerful. -

MATTHEW BRADLEY CV 2020 1 Page

MATTHEW BRADLEY CV www.matthewbradleystudio.com Bio 1969 Born, Adelaide, SA Selected Solo Exhibitions 2021 Anne and Gordon Samstag Museum, Adelaide (forthcoming) 2020 GAGPROJECTS | Greenaway Art Gallery, Adelaide (forthcoming) 2016 A Forest of Lightning, Australian Experimental Art Foundation, Adelaide Destroyer of Worlds, GAGPROJECTS | Greenaway Art Gallery, Adelaide 2012 Space Chickens Help Me Make Apple Pie, Fontanelle Gallery, Adelaide 2011 New Vehicles and Exploration, Greenaway Art Gallery, Adelaide 2010 Axle Mace, Contemporary Art Centre of South Australia, Adelaide 2008 Terminator, Greenaway Art Gallery, Adelaide 2007 Storm Machine, Gertrude Contemporary Art Space, Melbourne 2006 Te Good Son, Canberra Contemporary Art Space, Canberra 2005 Te Weet Bix Kid, Australian Experimental Art Foundation, Adelaide Empire, Screening room, Institute of Modern Art, Brisbane 2004 Dark Crystal, Te Project Space, Contemporary Art Centre of South Australia Empire, Downtown Art Space, Adelaide 2003 Helicopter Drawing, Artspace, Adelaide Festival Centre, Adelaide 1999 Te Nola Rose Candidate, Australian Experimental Art Foundation, Adelaide Selected Group Exhibitions 2019 Still Life, LON Gallery, Melbourne Floral Arrangements, A Flat, Adelaide SPACE, Gippsland Art Gallery, Victoria Other Suns, Fremantle Art Centre, Western Australia 2018 Directors Cut, FELTspace, Adelaide 2017 Te National 2017: New Australian Art, Museum of Contemporary Art, Sydney Born Under Punches, Format, Adelaide 2016 Dug and Digging With, Australian Experimental Art Foundation, -

Coca-Cola Stage Backgrounder 2016

May 26, 2016 BACKGROUNDER 2016 Coca-Cola Stage lineup Christian Hudson Appearing Thursday, July 7, 7 p.m. Website: http://www.christianhudsonmusic.com/ Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/ChristianHudsonMusic Twitter: www.twitter.com/CHsongs While most may know Christian Hudson by his unique and memorable performances at numerous venues across Western Canada, others seem to know him by his philanthropy. This talented young man won the prestigious Calgary Stampede Talent Show last summer but what was surprising to many was he took his prize money of $10,000 and donated it all to the local drop-in centre. He was touched by the stories he was told by a few people experiencing homelessness he had met one night prior to the contest’s finale. His infectious originals have caught the ears of many in the industry that are now assisting his career. He was honoured to receive 'The Spirit of Calgary' Award at the inaugural Vigor Awards for his generosity. Hudson will soon be touring Canada upon the release of his first single on national radio. JJ Shiplett Appearing Thursday, July 7, 8 p.m. Website: http://www.jjshiplettmusic.com/ Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/jjshiplettmusic/ Twitter: www.twitter.com/jjshiplettmusic Rugged, raspy and reserved, JJ Shiplett is a true artist in every sense of the word. Unapologetically himself, the Alberta born singer-songwriter and performer is both bold in range and musical creativity and has a passion and reverence for the art of music and performance that has captured the attention of music fans across the country. He spent the major part of early 2016 as one of the opening acts on the Johnny Reid tour and is also signed to Johnny Reid’s company. -

Wonderlust: the Influence of Natural History Illustration and Ornamentation on Perceptions of the Exotic in Australia

Wonderlust: the influence of natural history illustration and ornamentation on perceptions of the exotic in Australia. College of Arts and Social Sciences Research School of Humanities and the Arts School of Art Visual Arts Graduate Program Doctor of Philosophy Nicola Jan Dickson Exegesis presented in partial fulfillment of the requirements of the Doctor of Philosophy March 2010 1 Exegesis of Studio Research Declaration of Originality I, ……………………………………………(signature and date) hereby declare that the thesis here presented is the outcome of the research project undertaken during my candidacy, that I am the sole author unless otherwise indicated, and that I have fully documented the source of ideas, references, quotations and paraphrases attributable to other authors. 2 Acknowledgements I am grateful for the support and critical feedback of the various people who have had been on my supervisory panel at different times. These include Vivienne Binns, Nigel Lendon, Chaitanya Sambrani and Deborah Singleton. I would specifically like to acknowledge the constructive criticism that Ruth Waller has provided and her establishment of a constructive and engaging environment for post-graduate painting students at the ANU School of Art. I would also like to thank Patsy Hely, Raquel Ormella, Robert Boynes and Patsy Payne who have all readily offered advice. The insightful encouragement from other post- graduate peers strengthened my research and resolve. I would particularly like to thank Suzanne Moss, Ella Whateley, Jude Rae and Hanna Hoyne. Thanks also go to Kerri Land, Angela Braniff and my daughter Kathryn who have provided help installing the examination exhibition. Advice from Georgina Buckley regarding use of the Endnote program has been invaluable and much appreciated. -

From China to Chess!

an Hill I , 2010, scorched , 2010, scorched The Great War , RO I ORDE C & Sean ealy H Claire Claire coasters, beer bottles, hammers, 120 x 140 80 cm, courtesy timber, photograph by the artists and Gallery Barry Keldoulis, Sydney, www.unisa.edu.au/samstagmuseum Media Release From China to Chess! As the Samstag Museum of Art says farewell to White Rabbit – Contemporary Chinese Art Collection, the most highly visited exhibition of the year, Samstag welcomes two new exhibitions to complete its exciting 2011 program: Your Move: Australian artists play chess University of South Australia Bill Henson: early work from the MGA Collection, with selected recent landscapes 14 October – 16 December Adelaide SA 5000 55 North Terrace Your Move: Australian artists play chess has provided thirteen of Australia’s leading contemporary Samstag Museum of Art Anne & Gordon artists with the opportunity to engage with an ancient game to create new and intriguing works of art. ‘The game of chess is traditionally perceived as a subdued, cerebral and introspective activity’, exhibition curator Tansy Curtin said. ‘However, the creation of new artworks informed by the notion of the game of chess adds a new dimension to the game itself: chess acquires a new visual persona; beauty and drama alongside intrigue and threat become implicit aspects of the game’. This playful and thought-provoking exhibition engages with multiple concepts – from climate change, environmental degradation and the impacts of colonisation, to explorations of Australian icons – and vividly illustrates that in the 21st century, chess has lost none of its inspirational power. For many artists the game of chess is an allegory for battles throughout history; such as in the work of 2006 Samstag Scholars Claire Healy & Sean Cordeiro, whose work combines beer bottles and coasters on a scorched picnic table as metaphor for the First World War. -

Disclaimer—& 71 Book Quotes

Links within “Main” & Disclaimer & 71 Book Quotes 1. The Decoration of Independence - Upload (PDF) of Catch Me If You Can QUOTE - Two Little Mice (imdb) 2. know their rights - State constitution (United States) (Wiki) 3. cop-like expression - Miranda warning (wiki) 4. challenge the industry - Hook - Don’t Mess With Me Man, I’m A Lawyer (Youtube—0:04) 5. a fairly short explanation of the industry - Big Daddy - That Guy Doesn’t Count. He Can’t Even Read (Youtube—0:03) 6. 2 - The Prestige - Teach You How To Read (Youtube—0:12) 7. how and why - Upload (PDF) of Therein lies the rub (idiom definition) 8. it’s very difficult just to organize the industry’s tactics - Upload (PDF) of In the weeds (definition—wiktionary) 9. 2 - Upload (PDF) of Tease out (idiom definition) 10. blended - Spaghetti junction (wiki) 11. 2 - Upload (PDF) of Foreshadowing (wiki) 12. 3 - Patience (wiki) 13. first few hundred lines (not sentences) or so - Stretching (wiki) 14. 2 - Warming up (wiki) 15. pictures - Mug shot (wiki) 16. not much fun involved - South Park - Cartmanland (GIF) (Giphy) (Youtube—0:12) 17. The Cat in the Hat - The Cat in the Hat (wiki) 18. more of them have a college degree than ever before - Correlation and dependence (wiki) 19. hopefully someone was injured - Tropic Thunder - We’ll weep for him…In the press (GetYarn) (Youtube—0:11) 20. 2 - Wedding Crashers - Funeral Scene (Youtube—0:42) 21. many cheat - Casino (1995) - Cheater’s Justice (Youtube—1:33) 22. house of representatives - Upload (PDF) Pic of Messy House—Kids Doing Whatever—Parent Just Sitting There & Pregnant 23. -

Proceedings, the 77Th Annual Meeting, 2001

PROCEEDINGS The 77th Annual Meeting 2001 NATIONAL ASSOCIATION OF SCHOOLS OF MUSIC NUMBER 90 JULY 2002 PROCEEDINGS The 77th Annual Meeting 2001 NATIONAL ASSOCIATION OF SCHOOLS OF MUSIC © 2002 by the National Association of Schools of Music. All rights reserved including the right to reproduce this book or parts thereof in any form. ISSN 0190-6615 National Association of Schools of Music 11250 Roger Bacon Drive, Suite 21 Reston, Virginia 20190 Tel. (703) 437-0700 Web address: www.arts-accredit.org E-mail: [email protected] CONTENTS Preface vii Keynote Speech Music as Metaphor Jaroslav Pelikan 1 Alternative Certification: Threat Or Opportunity? Alternative Certification: Threat Or Opportunity? Janice Killian 15 Alternative Routes to Teacher Certification in Michigan Randi L'Hommedieu 20 Alternative Certification: Threat Or Opportunity? Michael Palumbo 25 Alternative Certification: Threat Or Opportunity? Mary Dave Blachnan 30 Rehearsals, Accompaniment And Scheduling: What Can New Technology Do? Rehearsals, Accompaniment And Scheduling: What Can New Technology Do? Timothy Hester 33 Theory Pedagogy: Current Trends, New Ideas Sparking the Connections between Theory Knowledge, Ear-Training, and the Daily Lives of Musicians: An Appropriate Role for Technology James Faulconer 46 Goals, Core Issues, and Suggestions for the Future in Music Theory Pedagogy Michael Rogers 50 Music Business Programs: Content and Achievement Music Business Programs: Content and Achievement Edward J. Kvet and Scott Fredrickson 57 Management Basics: Faculty Loads Faculty Workload: Current Practice and Future Directions Charlotte Collins 62 Open Forum: Historically Black Colleges and Universiti^ Historically Black Colleges and Universities Josephine C. Bell 68 Justifying the Need for Financial Support of Recruitment Programs and Scholarships with Limited Budgets Jimmie James, Jr. -

2004 SCHEDULE GAME 13 Released: December 10, 2004 HAWAI‘I (7-5, 4-4 WESTERN ATHLETIC CONFERENCE) Date Opponent Time VS

2004 SCHEDULE GAME 13 Released: December 10, 2004 HAWAI‘I (7-5, 4-4 WESTERN ATHLETIC CONFERENCE) Date Opponent Time VS. Sept. 4 FLORIDA ATLANTIC L, 28-35 UAB (7-4, 5-3 CONFERENCE USA) Sept. 18 at Rice * (Sportswest) L, 29-41 Oct. 2 TULSA * W, 44-16 GAME INFORMATION Oct. 9 NEVADA * W, 48-26 Friday, Dec. 24, 2004 Oct. 16 at UTEP * (ERT) L, 20-51 2:05 p.m. Oct. 23 SAN JOSE STATE * W, 46-28 Oct. 29 at Boise State * (ESPN2) L, 3-69 Aloha Stadium - Honolulu (50,000) Nov. 6 LOUISIANA TECH * W, 34-23 Nov. 12 at Fresno State * (ESPN) L, 14-70 TELEVISION: Live nationwide on ESPN with Dave Pasch calling the action, Rod Nov. 20 IDAHO W, 52-21 Gilmore and Trevor Matich providing color, and Rob Stone reporting from the sidelines. Nov. 27 NORTHWESTERN W, 49-41 NATIONALRADIO: Live on CBS Sports Westwood One Radio with Tony Roberts Dec. 4 MICHIGAN STATE (ESPN2) W, 41-38 calling the action. LOCAL RADIO: Live on KKEA Sportsradio 1420 AM with Bobby Curran calling the * denotes WAC game action Robert Kekaula providing color and John Veneri reporting from the sidelines. Don Robbs will host the pregame show “Warrior Tailgate” beginning at 1 pm., and also the halftime show. Live to the Neighbor Islands on KAOI on Maui/Kona, KPUA Hilo, and KQNG Kauai. TICKETS WEBCAST: Listen live on the internet at KKEA1420AM.com PARKING GATES: Parking lot gates at Aloha Stadium will open at 10 a.m. Parking is $5. Alternate parking is available at Leeward Community College (free with a $2 charge Tickets for the Sheraton Hawai‘i Bowl are on sale on-line of shuttle service, and at Kam Drive-In for $5 and free shuttle service.