Proceedings, the 77Th Annual Meeting, 2001

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

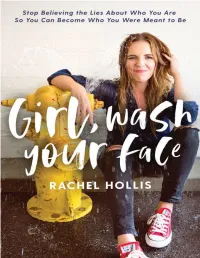

Girl, Wash Your Face

PRAISE FOR Girl, Wash Your Face “If Rachel Hollis tells you to wash your face, turn on that water! She is the mentor every woman needs, from new mommas to seasoned business women.” —ANNA TODD, New York Times and #1 internationally bestselling author of the After series “Rachel’s voice is the winning combination of an inspiring life coach and your very best (and funniest) friend. Shockingly honest and hilariously down to earth, Girl, Wash Your Face is a gift to women who want to flourish and live a courageously authentic life.” —MEGAN TAMTE, founder and co-CEO of Evereve “There aren’t enough women in leadership telling other women to GO FOR IT. We typically get the caregiver; we rarely get the boot camp instructor. Rachel lovingly but firmly tells us it is time to stop letting the tail wag the dog and get on with living our wild and precious lives. Girl, Wash Your Face is a dose of high-octane straight talk that will spit you out on the other end chasing down dreams you hung up long ago. Love this girl.” —JEN HATMAKER, New York Times bestselling author of For the Love and Of Mess and Moxie and happy online hostess to millions every week “In Rachel Hollis’s first nonfiction book, you will find she is less cheerleader and more life coach. This means readers won’t just walk away inspired, they will walk away with the right tools in hand to actually do their dreams. Dream doing is what Rachel is all about it. -

Note Staff Symbol Carnatic Name Hindustani Name Chakra Sa C

The Indian Scale & Comparison with Western Staff Notations: The vowel 'a' is pronounced as 'a' in 'father', the vowel 'i' as 'ee' in 'feet', in the Sa-Ri-Ga Scale In this scale, a high note (swara) will be indicated by a dot over it and a note in the lower octave will be indicated by a dot under it. Hindustani Chakra Note Staff Symbol Carnatic Name Name MulAadhar Sa C - Natural Shadaj Shadaj (Base of spine) Shuddha Swadhishthan ri D - flat Komal ri Rishabh (Genitals) Chatushruti Ri D - Natural Shudhh Ri Rishabh Sadharana Manipur ga E - Flat Komal ga Gandhara (Navel & Solar Antara Plexus) Ga E - Natural Shudhh Ga Gandhara Shudhh Shudhh Anahat Ma F - Natural Madhyam Madhyam (Heart) Tivra ma F - Sharp Prati Madhyam Madhyam Vishudhh Pa G - Natural Panchama Panchama (Throat) Shuddha Ajna dha A - Flat Komal Dhaivat Dhaivata (Third eye) Chatushruti Shudhh Dha A - Natural Dhaivata Dhaivat ni B - Flat Kaisiki Nishada Komal Nishad Sahsaar Ni B - Natural Kakali Nishada Shudhh Nishad (Crown of head) Så C - Natural Shadaja Shadaj Property of www.SarodSitar.com Copyright © 2010 Not to be copied or shared without permission. Short description of Few Popular Raags :: Sanskrut (Sanskrit) pronunciation is Raag and NOT Raga (Alphabetical) Aroha Timing Name of Raag (Karnataki Details Avroha Resemblance) Mood Vadi, Samvadi (Main Swaras) It is a old raag obtained by the combination of two raags, Ahiri Sa ri Ga Ma Pa Ga Ma Dha ni Så Ahir Bhairav Morning & Bhairav. It belongs to the Bhairav Thaat. Its first part (poorvang) has the Bhairav ang and the second part has kafi or Så ni Dha Pa Ma Ga ri Sa (Chakravaka) serious, devotional harpriya ang. -

Proper Education

he title mav not be all that original. Neither was it in 1872when Ellen G. White utilized it to launch her distineuished career as a philosopher of Christian education.A perusalof the literature of the times revealsthat the "educational expres- sions re[orm" "proper and education" seemedto be favorite buzzwordsin the press,ban- died about lreelv bv editors, politi- cians,and celebratedspeakers on the Chautauquacircuit who found it pop- ular to inveighagainst the impractical- ity of the classicalcurriculum. The Education" entrenchededucational establishment of the day, so re-sistantto change of By G.H. AKERS any sort, was a specialtarget of writers and speakers. Clearly, grassroots post-Civil War America was growing impatient with its schools.Elitist education,reserved for the upper classand essentiallvfor cosmeticcffcct was definitclvundr'r siegeas backward-orientcd,ex- hausted, and entirelv too static to respond to the needs o[ the r<_rbust new socialorder. The times called for a more appropriatecducational product-trained artisans, surveyors, architccts,engineers, technicians, ser- vice professionals,busincss lcaders, "Can and practitioncrs of cvery sort. Do" had bccomethe order of thc.dar, and Amcrica'scollcgcs and univerii- ties wcre expccted to help substan- tiallvin achicvingthe maniicst dcstinr of an exuberant, expanding voung countrv. A ]lew Voice to Society and Ghurch It was in this latenineteenth-centurv culturalcontext, with tht'GreatCon- versationmoving from coast to coast regarding the appropriate training of the young, that Ellen White moved in "Proper with her landmark essav Edu- cation."In it sheoffcrci hcr own orc- scriptionfor wt.rrthyeducational goals for socicty and church and the best methods for their acc<-rmplishmcnt. -

Johnny O'neal

OCTOBER 2017—ISSUE 186 YOUR FREE GUIDE TO THE NYC JAZZ SCENE NYCJAZZRECORD.COM BOBDOROUGH from bebop to schoolhouse VOCALS ISSUE JOHNNY JEN RUTH BETTY O’NEAL SHYU PRICE ROCHÉ Managing Editor: Laurence Donohue-Greene Editorial Director & Production Manager: Andrey Henkin To Contact: The New York City Jazz Record 66 Mt. Airy Road East OCTOBER 2017—ISSUE 186 Croton-on-Hudson, NY 10520 United States Phone/Fax: 212-568-9628 NEw York@Night 4 Laurence Donohue-Greene: Interview : JOHNNY O’NEAL 6 by alex henderson [email protected] Andrey Henkin: [email protected] Artist Feature : JEN SHYU 7 by suzanne lorge General Inquiries: [email protected] ON The Cover : BOB DOROUGH 8 by marilyn lester Advertising: [email protected] Encore : ruth price by andy vélez Calendar: 10 [email protected] VOXNews: Lest We Forget : betty rochÉ 10 by ori dagan [email protected] LAbel Spotlight : southport by alex henderson US Subscription rates: 12 issues, $40 11 Canada Subscription rates: 12 issues, $45 International Subscription rates: 12 issues, $50 For subscription assistance, send check, cash or VOXNEwS 11 by suzanne lorge money order to the address above or email [email protected] obituaries Staff Writers 12 David R. Adler, Clifford Allen, Duck Baker, Fred Bouchard, Festival Report Stuart Broomer, Robert Bush, 13 Thomas Conrad, Ken Dryden, Donald Elfman, Phil Freeman, Kurt Gottschalk, Tom Greenland, special feature 14 by andrey henkin Anders Griffen, Tyran Grillo, Alex Henderson, Robert Iannapollo, Matthew Kassel, Marilyn Lester, CD ReviewS 16 Suzanne Lorge, Mark Keresman, Marc Medwin, Russ Musto, John Pietaro, Joel Roberts, Miscellany 41 John Sharpe, Elliott Simon, Andrew Vélez, Scott Yanow Event Calendar Contributing Writers 42 Brian Charette, Ori Dagan, George Kanzler, Jim Motavalli “Think before you speak.” It’s something we teach to our children early on, a most basic lesson for living in a society. -

Richard Strauss's Ariadne Auf Naxos

Richard Strauss’s Ariadne auf Naxos - A survey of the major recordings by Ralph Moore Ariadne auf Naxos is less frequently encountered on stage than Der Rosenkavalier or Salome, but it is something of favourite among those who fancy themselves connoisseurs, insofar as its plot revolves around a conceit typical of Hofmannsthal’s libretti, whereby two worlds clash: the merits of populist entertainment, personified by characters from the burlesque Commedia dell’arte tradition enacting Viennese operetta, are uneasily juxtaposed with the claims of high art to elevate and refine the observer as embodied in the opera seria to be performed by another company of singers, its plot derived from classical myth. The tale of Ariadne’s desertion by Theseus is performed in the second half of the evening and is in effect an opera within an opera. The fun starts when the major-domo conveys the instructions from “the richest man in Vienna” that in order to save time and avoid delaying the fireworks, both entertainments must be performed simultaneously. Both genres are parodied and a further contrast is made between Zerbinetta’s pragmatic attitude towards love and life and Ariadne’s morbid, death-oriented idealism – “Todgeweihtes Herz!”, Tristan und Isolde-style. Strauss’ scoring is interesting and innovative; the orchestra numbers only forty or so players: strings and brass are reduced to chamber-music scale and the orchestration heavily weighted towards woodwind and percussion, with the result that it is far less grand and Romantic in scale than is usual in Strauss and a peculiarly spare ad spiky mood frequently prevails. -

Simple Plan: Nuovo Tour E Nuovo Album Per La Band Pop Punk Di

LUNEDì 30 NOVEMBRE 2015 I Simple Plan, band di Montreal, arriva, finalmente in Italia, per due richiestissime date italiane. I Simple Plan saliranno sul palco dell'Estragon di Bologna il 1° marzo 2016 e su quello Simple Plan: nuovo tour e nuovo dell'Alcatraz di Milano il 2 marzo 2016 per quelli che saranno due show album per la band pop punk di spettacolari fatti da tutti i successi e le tracks del nuovo album "Taking Montreal! One For The Team" in uscita il 19 febbraio, per Warner Music Italy. Il Taking One For The Team Tour li riporta sui palchi di tutto il mondo. Il All'Estragon di Bologna il 1°marzo 2016 e loro quinto album, Taking One For The Team, è stato introdotto dal all'Alcatraz di Milano il 2 marzo 2016 super singoloI Don't Want To Go To Bed, nel cui video appare il bagnino più famoso di sempre: David Hasselhoff. LA REDAZIONE Special guest delle date italiane la band electronicore americana Ghost Town. Dopo una lunga serie di tour nel 2015, durante i quali sono arrivati anche a Treviso per l'Home Festival e a Roma come super guest dei Linkin Park, [email protected] la band si è messa a lavoro sul disco che promette sonorità cross over tra SPETTACOLINEWS.IT punk e pop, lyrics orecchiabili e la solita dose di positività che li ha sempre definiti come gruppo. Il gruppo si forma ufficialmente nel 1999 tra i banchi delle superiori, da una precedente band chiamata Reset. In un'intervista il chitarrista della band, Sébastien Lefebrve, ha dichiarato che dopo aver visto il film di Sam Raimi, 'A Simple Plan', ha pensato che fosse un nome perfetto per il gruppo. -

(WA Opera Society

W.A.OPERA COMPANY (W.A. Opera Society - Forerunner) PR9290 Flyers and General 1. Faust – 14th to 23rd August; and La Boheme – 26th to 30th August. Flyer. 1969. 2. There’s a conspiracy brewing in Perth. It starts September 16th. ‘A Masked Ball’ Booklet. c1971. D 3. The bat comes to Perth on June 3. Don’t miss it. Flyer. 1971. 4. ‘The Gypsy Baron’ presented by The W.A. Opera Company – Gala Charity Premiere. Wednesday 10th May, 1972. Flyer. 5. 2 great love operas. Puccini’s ‘Madame Butterfly’ ; Rossini’s ‘The Barber of Seville’ on alternate nights. September 14-30. Flyer. 1972. D 6. ‘Rita’ by Donizetti and ‘Gallantry’ by Douglas Moore. Sept. 9th-11th, & 16th, 17th. 1p. flyer. c1976. 7. ‘Sour Angelica’ by Puccini, Invitation letter to workshop presentation. 1p..Undated. 8. Letter to members about Constitution Amendments. 2p. July 1976. 9. Notice of Extraordinary General Meeting re Constitution Change. 1p. 7 July 1976. 10. Notice of Extraordinay General Meeting – Agenda and Election Notice. 1p. July 1976. 11. Letter to Members summarising events occurring March – June 1976. 1p. July 1976. 12. Memo to Acting Interim Board of Directors re- Constitutional Developments and Confrontation Issues. 3p. July 1976. 13. Campaign letter for election of directors on to the Board. 3p. 1976. 14. Short Biographies on nominees for Board of Directors. 1p.. 1976. 15. Special Priviledge Offer. for ‘The Bear’ by William Walton and ‘William Derrincourt’ by Roger Smalley. 1p. 1977. 16. Membership Card. 1976. 17. Concession Vouchers for 1976 and 1977. 18. The Western Australian Opera Company 1980 Season. -

Evaluation of the Effects of Music Therapy Using Todi Raga of Hindustani Classical Music on Blood Pressure, Pulse Rate and Respiratory Rate of Healthy Elderly Men

Volume 64, Issue 1, 2020 Journal of Scientific Research Institute of Science, Banaras Hindu University, Varanasi, India. Evaluation of the Effects of Music Therapy Using Todi Raga of Hindustani Classical Music on Blood Pressure, Pulse Rate and Respiratory Rate of Healthy Elderly Men Samarpita Chatterjee (Mukherjee) 1, and Roan Mukherjee2* 1 Department of Hindustani Classical Music (Vocal), Sangit-Bhavana, Visva-Bharati (A Central University), Santiniketan, Birbhum-731235,West Bengal, India 2 Department of Human Physiology, Hazaribag College of Dental Sciences and Hospital, Demotand, Hazaribag 825301, Jharkhand, India. [email protected] Abstract Several studies have indicated that music therapy may affect I. INTRODUCTION cardiovascular health; in particular, it may bring positive changes Music may be regarded as the projection of ideas as well as in blood pressure levels and heart rate, thereby improving the emotions through significant sounds produced by an instrument, overall quality of life. Hence, to regulate blood pressure, music voices, or both by taking into consideration different elements of therapy may be regarded as a significant complementary and alternative medicine (CAM). The respiratory rate, if maintained melody, rhythm, and harmony. Music plays an important role in within the normal range, may promote good cardiac health. The everyone’s life. Music has the power to make one experience aim of the present study was to evaluate the changes in blood harmony, emotional ecstasy, spiritual uplifting, positive pressure, pulse rate and respiratory rate in healthy and disease-free behavioral changes, and absolute tranquility. The annoyance in males (age 50-60 years), at the completion of 30 days of music life may increase in lack of melody and harmony. -

''Proper Education''

33 ADVENTIST PERSPECTIVES, Spring, 1989, Vol. II I, No. 1 ''Proper Education'' by G. H. Akers Dr. George H. Akers, currently "Mr. Education" for the Seventh-day Adventist world church, absorbed the educational wisdom of a one-room church school, an academy in the sweeping Shenandoah Valley, and Washington Missionary College (CUC). Teaching, cleaning, and administering education at various levels have been his life for more than forty years of serv ice to his church and his God. His doctorate in higher education and historical/philosophical foundations was earned at USCLA. Some sixteen years at Andrews University climaxed with his appointment to the first deanship of the School of Education. Dr. Akers' lively communicative style brings a refreshing touch to Adventist Perspectives as he writes of ''Proper Education" and Ellen White's relationship to it in the Seventh-day Adventist Church. he above title mav not be surveyors, architects, engineers, tech all that original. Neither nicians, service professionals, business was it in 1872 when Ellen leaders, and practitioners of every sort. G. White utilized it to "Can Do" had become the order of the T launch her distinguished day, and America's colleges and uni career as a philosopher of Christian versities were expected to help sub education. A perusal of the literature of stantially in achieving the manifest the times reveals that the expressions destiny of an exuberant, expanding "L~ucational reform" and "properedu young country. cation" seemed to be tavorite buzzwords in the press, bandied about .4 Nelv Voice to Society freely by editors, politicians, and cele and Clzurclt brated speakers on the Chautauqua circuit who found it popular to inveigh It was in this late nineteenth-century against the impracticality of the classi cultural context, with the Great Con versation moving from coast to coast cal curriculum. -

Wagner March 06.Indd

Wagner Society in NSW Inc. Newsletter No. 103, March 2006 IN NEW SOUTH WALES INC. President’s Report In Memoriam While on the subject of recordings, we are still waiting for the first opera of the promised set from the Neidhardt Birgit Nilsson, the Wagner Soprano Legend, Ring in Adelaide in 2004, and regretting that last year’s Dies at 87 and Tenor James King at 80 triumphal Tristan in Brisbane with Lisa Gasteen and John Birgit Nilsson, the Swedish soprano, died on 25 December Treleaven went unrecorded. 2005 at the age of 87 in Vastra Karup, the village where Functions she was born. Max Grubb has specially written for the Newsletter an extensive appraisal and appreciation of the On 19 February, we held our first function of 2006, at which voice, career and character of Nilsson (page 10). Nilsson’s Professor Kim Walker, Dean of the Sydney Conservatorium regular co-singer, Tenor James King has also died at eighty: of Music, spoke about the role of the Conservatorium, Florida, 20 November 2005 (see report page 14). the work of the Opera Studies Unit in particular, and the need to find private funding to replace government grants A LETTER TO MEMBERS which have been severely cut. Sharolyn Kimmorley then Dear Members conducted a voice coaching class with Catherine Bouchier, a voice student at the Con. From feedback received at and Welcome to this, our first Newsletter for 2006, in which since the function, members attending found this “master we mourn the passing of arguably the greatest Wagnerian class” a fascinating and rewarding window onto the work soprano of the second half of the 20th century, Birgit of the Conservatorium, and I’d like on your behalf to once Nilsson. -

A Study on the Effects of Music Listening Based on Indian Time Theory of Ragas on Patients with Pre-Hypertension

International Journal of Scientific & Engineering Research Volume 9, Issue 1, January-2018 ISSN 2229-5518 370 A STUDY ON THE EFFECTS OF MUSIC LISTENING BASED ON INDIAN TIME THEORY OF RAGAS ON PATIENTS WITH PRE-HYPERTENSION Suguna V Masters in Indian Music, PGD in Music Therapy IJSER IJSER © 2018 http://www.ijser.org International Journal of Scientific & Engineering Research Volume 9, Issue 1, January-2018 ISSN 2229-5518 371 1. ABSTRACT 1.1 INTRODUCTION: Pre-hypertension is more prevalent than hypertension worldwide. Management of pre- hypertensive state is usually with lifestyle modifications including, listening to relaxing music that can help in preventing the progressive rise in blood pressure and cardio-vascular disorders. This study was taken up to find out the effects of listening to Indian classical music based on time theory of Ragas (playing a Raga at the right time) on pre-hypertensive patients and how they respond to this concept. 1.2 AIM & OBJECTIVES: It has been undertaken with an aim to understand the effect of listening to Indian classical instrumental music based on the time theory of Ragas on pre-hypertensive patients. 1.3 SUBJECTS & METHODS: This study is a repeated measure randomized group designed study with a music listening experimental group and a control group receiving no music intervention. The study was conductedIJSER at Center for Music Therapy Education and Research at Mahatma Gandhi medical college and research institute, Pondicherry. 30 Pre-hypertensive out patients from the Department of General Medicine participated in the study after giving informed consent form. Systolic BP (SBP), Diastolic BP (DBP), Pulse Rate (PR) and Respiratory Rate (RR) measures were taken on baseline and every week for a month. -

— Dante E Il Rock

Numero 6, 2019 ISSN 2385-5355 (digital) • ISSN 2385-7269 (paper) http://revistes.uab.cat/dea 6 — Dante e il rock Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona Institut d’Estudis Medievals Bellaterra, 2019 Dante e l’Arte è una rivista dell’Institut d’Estudis Medievals attivo all’in- terno dell’Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona (UAB). È stata fondata nel 2014 da Rossend Arqués e Eduard Vilella perché fosse un punto di riferimento delle iniziative relative agli studi sul rapporto tra Dante e l’arte sia all’interno dell’opera dantesca sia nella sua ricezione. Il suo obiettivo è fungere da mezzo di diffusione delle ricerche originali in questo specifico ambito grazie alla pubblicazione di studi che provengano da tutto il mondo, nella convinzione che l’argomento debba essere affrontato a livello mondiale con lo sguardo rivolto ai rapporti esistenti tra le forme artistiche sviluppatesi nei diversi paesi e l’opera dantesca. La rivista pubblica lavori originali in dossier monografici, articoli di ricerca, note e recensioni di opere pubblicate nel mondo che si sono occupate di questo argomento. L’accettazione degli articoli segue le norme del sistema di valutazione per esperti esterni (peer review). Direzione Barbara Stoltz Philippe Guerin Juan Miguel Valero Rossend Arqués Universität Marburg Université Paris 3 Universidad de Salamanca Universitat Autònoma Comitato scientifico Cornelia Klettke Juan Varela Portas de Barcelona Universitát Potsdam de Orduña Roberto Antonelli Universidad Complutense Eduard Vilella Università di Roma Barbara Kuhn de Madrid Universitat