Essays: Archaeologists and Missionaries

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

RISSIONS and MISSIONARIES PIETER N. HOLTROP and HUGH

RISSIONS AND MISSIONARIES EDITED BY PIETER N. HOLTROP and HUGH McLEOD PUBLISHED FOR THE ECCLESIASTICAL HISTORY SOCIETY BY THE BOYDELL PRESS 2000 CONTENTS List of Contributors vii Editors' Preface ix List of Abbreviations x The Vernacular and the Propagation of the Faith in Anglo-Saxon Missionary Activity i ANNA MARIA LUISEIXI FADDA St Willibrord in Recent Historiography 16 EUGÈNE HONÉE Political Rivalry and Early Dutch Reformed Missions in Seventeenth-Century North Sulawesi (Celebes) 32 HENDRIK E. NIEMEIJER The Beliefs, Aspirations and Methods of the First Missionaries in British Hong Kong, 1841-5 50 KATE LOWE Civilizing the Kingdom: Missionary Objectives and the Dutch Public Sphere Around 1800 65 JORIS VAN EIJNATTEN Language, 'Native Agency', and Missionary Control: Rufus Anderson's Journey to India, 1854-5 81 ANDREW PORTER Why Protestant Churches? The American Board and the Eastern Churches: Mission among 'Nominal' Christians (1820-70) 98 H. L. MURRE-VAN DEN BERG Modernism and Mission: The Influence of Dutch Modern Theology on Missionary Practice in the East Indies in the Nineteenth Century 112 GUUS BOONE 'Hunting for Souls': The Missionary Pilgrimage of George Sherwood Eddy 127 BRIAN STANLEY CONTENTS The Governor a Missionary? Dutch Colonial Rule and Christianization during Idenburg's Term of Office as Governor of Indonesia (1909-16) 142 PIETER N. HOLTROP Re-reading Missionary Publications: The Case of European and Malagasy Martyrologies, 1837-1937 157 RACHEL A. RAKOTONIRINA Women in the Irish Protestant Foreign Missions c. 1873-1914: Representations and Motivations 170 MYRTLE HILL There is so much involved ...' The Sisters of Charity of Saint Charles Borromeo in Indonesia in the Period from the Second World War 186 LIESBETH LABBEKE Missionaries, Mau Mau and the Christian Frontier 200 JOHN CASSON Index 217 VI WHY PROTESTANT CHURCHES? THE AMERICAN BOARD AND THE EASTERN CHURCHES: MISSION AMONG 'NOMINAL' CHRISTIANS (1820-70) by H. -

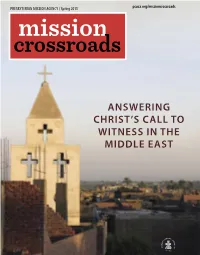

Answering Christ's Call to Witness in the Middle East

PRESBYTERIAN MISSION AGENCY / Spring 2015 pcusa.org/missioncrossroads mission ANSWERING CHRIST’S CALL TO WITNESS IN THE MIDDLE EAST AT THE CROSSROADS | By Amgad Beblawi, World Mission Area Coordinator for the Middle East and Europe Mission Crossroads is a Seeing the Middle East Presbyterian Mission Agency publication about the church’s through Christ’s call mission around the world. As reports of turmoil and conflict in the Middle East continue Presbyterian World Mission is to make news headlines, Western governments continue to committed to sending mission deliberate and strategize how to protect their national interests in personnel, empowering the the region. global church, and equipping On the other hand, the church’s outlook and response to events the Presbyterian Church (USA.) in the world is diametrically different. Compelled by the love for mission as together we address of God, the church responds to Christ’s call – “you will be my the root causes of poverty, work for witnesses” (Acts 1:8). reconciliation amidst cultures Christians in the Middle East have, in fact, been Christ’s witnesses since the Day of Pentecost. Successive generations of Christ’s followers proclaimed the of violence, and share the good Gospel to the region’s inhabitants for the past two millennia. However, since the dawn of Islam in news of God’s saving love the seventh century, Christians gradually became a small minority. By the beginning of the 19th through Jesus Christ. century, Orthodox, Assyrian, Maronite, and Eastern Catholic churches that trace their origin to the Apostolic Era were in a state of decline. EDITOR Presbyterian churches in the US and Scotland heard God’s call to send missionaries to Kathy Melvin strengthen indigenous churches in the land where Christianity had its cradle. -

The Clarion of Syria

AL-BUSTANI, HANSSEN,AL-BUSTANI, SAFIEDDINE | THE CLARION OF SYRIA The Clarion of Syria A PATRIOT’S CALL AGAINST THE CIVIL WAR OF 1860 BUTRUS AL-BUSTANI INTRODUCED AND TRANSLATED BY JENS HANSSEN AND HICHAM SAFIEDDINE FOREWORD BY USSAMA MAKDISI The publisher and the University of California Press Foundation gratefully acknowledge the generous support of the Simpson Imprint in Humanities. The Clarion of Syria Luminos is the Open Access monograph publishing program from UC Press. Luminos provides a framework for preserving and rein- vigorating monograph publishing for the future and increases the reach and visibility of important scholarly work. Titles published in the UC Press Luminos model are published with the same high standards for selection, peer review, production, and marketing as those in our traditional program. www.luminosoa.org The Clarion of Syria A Patriot’s Call against the Civil War of 1860 Butrus al-Bustani Introduced and Translated by Jens Hanssen and Hicham Safieddine Foreword by Ussama Makdisi university of california press University of California Press, one of the most distinguished university presses in the United States, enriches lives around the world by advancing scholarship in the humanities, social sciences, and natural sciences. Its activities are supported by the UC Press Foundation and by philanthropic contributions from individuals and institutions. For more information, visit www.ucpress.edu. University of California Press Oakland, California © 2019 by Jens Hanssen and Hicham Safieddine This work is licensed under a Creative Commons CC-BY-NC license. To view a copy of the license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Names: Hanssen, Jens, author & translator. -

Personal Papers

Personal Papers This is not a complete listing of all individuals for whom the Yale Divinity Library holds papers. For thorough searching, please use the Yale Finding Aid Database. See also microform collections such as "Women’s lives. Series 3, American women missionaries and pioneers collection" - University of Oregon Libraries. (Film Ms467) When an online finding aid for a collection is available, the record group number (e.g., RG 8) is linked to it. Hard copies are available for all record groups in the Special Collections Reading Room. Also available online is a geographical index grouping individuals and organizations by continent, region or country. For a list of abbreviations used in this chart, click here. Jump to: A B C D E F G H I J K L M N O P Q R S T U V W Y Z Abbott, Edward (RG 8) Collection of 57 photographs taken in China (1896-1900) primarily at American Church Mission stations and institutions. Also of interest: Imperial Examination cells at Nanking, Chinese Prayer Book Revision Committee. (.5 linear ft.) Abbott, James (Film Ms.121) Missionary for the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-Day Saints in New Zealand (1892-1896). (1 reel) Ableson, Bradford Edward (RG Prominent Yale Divinity School graduate, Captain in the Chaplain 222) Corps of the U.S. Navy, and clergyman. (11 linear ft.) Adams, Archibald (RG 8) ABFMS missionary to China, stationed in Suifu (Yibin) and Kiating (Leshan), Sichuan prov. (1914-1926); correspondence, writings, photographs of Peking, Western China, Buddhist funeral, people at work, etc. (1 linear ft.) Adams, Marie (RG 8) MEFB missionary in Peking (1915-1950); memoir, photographs and watercolors in silk cases, incl. -

Kiepert's Maps After Robinson and Smith

Haim Goren, Bruno Schelhaas Kiepert’s Maps after Robinson and Smith: Revolution in Re-Identifying the Holy Land in the Nineteenth Century Summary In the long history of Palestine research one interesting devel- aus den USA stammende Theologe Edward Robinson in Be- opment has to be noted. In the 19th century the Holy Land gleitung des Missionars Eli Smith eine Reise durch das Hei- was ‘rediscovered’, leading to the detailed use of all existing lige Land. Ihre Vorreiterrolle in der Erforschung des Heili- sources, the foremost being the Scriptures. The US theologian gen Landes und die ausführliche Rekonstruktion der Bibel als Edward Robinson, accompanied by the missionary Eli Smith, historisch-geographische Quelle wurde von ihren Zeitgenos- traveled in the Holy Land in 1838. The pioneering role in Holy sen anerkannt und stellte einen Meilenstein auf dem Weg der Land research, the detailed reconstruction of the Scriptures Palästinaforschung zur akademischen Disziplin dar. Ergebnis as a historical-geographical source was accepted by contempo- der Reise war ein umfassendes dreibändiges Werk, das mehre- raries – a milestone in the process of establishing Palestine re- re Karten des jungen Kartographen Heinrich Kiepert enthielt. search as a modern academic discipline. The voyage yielded a Mit diesen Karten wurde ein neues Narrativ im historisch- detailed, three-volume work, including various maps drawn by geographischen Diskurs eingeführt, das zu einer neuen Iden- the young cartographer Heinrich Kiepert. These maps estab- titätskonstruktion des Heiligen Landes führte. lished a new narrative within the historical-geographical dis- Keywords: Palästinaforschung; Kartographiegeschichte; Ed- course, leading to a new construction of the identity of the ward Robinson; Eli Smith; Heinrich Kiepert Holy Land. -

Toward a Conceptual History of Nafir Suriyya Jens Hanssen

Chapter 4 Toward a Conceptual History of Nafir Suriyya jens hanssen Both words of the title of al-Bustani’s pamphlets require inves- tigation, as well as his definition of them as wataniyyat: What did he mean by nafir and what would have been its connotations? And what did Suriyya mean to al-Bustani and his generation? Was it a description of a real territory or a potentiality? al-Nafir and Suriyya are terms that go back to antiquity, but neither had much traction outside liturgical literature until contact with Protestant missionaries gave them new political valence. al-Nafīr means “clarion” or “trumpet,” which was perhaps so self-evident that al-Bustani did not explain the term in his pamphlets.1 But in Muhit al-Muhit, he dedicated almost an entire page to the different declinations and meanings of the rootn-f-r (from the “bolting of a mare,” to “raising of troops,” “the fugi- tive,” “estrangement,” and “mutual aversion”), before defin- ing al-nafir itself: “someone enlisted in a group or cause,” and “al-nafir al-ʿam means mass mobilization to combat the enemy.” The Protestant convert al-Bustani also lists yawm al-nafir (Judgment Day)2 and informs the reader that al-nafir is also a trumpet or fanfare (al-buq)3 containing associations with Israfil, 45 46 / Chapter 4 the archangel of death alluded to in the Bible and the Quran.4 Then he mentions Nafir Suriyya itself as a set of “meditations on the events of 1860 published in eleven issues that we called wataniyyat.” Like many historians before us, we translate the term as “ clarion” in order to capture both the apocalyptic mood of the text and the author’s passionate call for social concord and overcoming adversity.5 At first sight, the term Suriyya is less complex. -

Presbyterians in Persia: Christianity, Cooperation, and Control in Building the Mission at Orumiyeh

Presbyterians in Persia: Christianity, Cooperation, and Control in Building the Mission at Orumiyeh by Natalie Kidwell Submitted to the Department of History of the University of Kansas in partial fulfillment of the requirements for departmental honors Approved by: _________________________ Dr. Marie Brown Thesis Adviser _________________________ Dr. Anton Rosenthal Committee Member _________________________ Dr. Sam Brody Committee Member _________________________ Date Defended Kidwell 1 Table of Contents Introduction .......................................................................................................................................................................................2-3 Persia and Presbyterians ................................................................................................................................................................... 4 Persian government and foreign powers at play ........................................................................................................... 7-11 Education in Persia ................................................................................................................................................................. 12-14 Western Christianity in Persia ............................................................................................................................................ 15-25 Dwight and Smith ........................................................................................................................................................................... -

Medieval Shiloh—Continuity and Renewal

religions Article Medieval Shiloh—Continuity and Renewal Amichay Shcwartz 1,2,* and Abraham Ofir Shemesh 1 1 The Israel Heritage Department, Faculty of Social Sciences and Humanities, Ariel University, Kiryat Hamada Ariel 40700, Israel; [email protected] 2 The Department of Middle Eastern Studies, Bar-Ilan University, Ramat-Gan 5290002, Israel * Correspondence: [email protected] Received: 25 August 2020; Accepted: 22 September 2020; Published: 27 September 2020 Abstract: The present paper deals with the development of cult in Shiloh during the Middle Ages. After the Byzantine period, when Shiloh was an important Christian cult place, it disappeared from the written sources and started to be identified with Nebi Samwil. In the 12th century Shiloh reappeared in the travelogues of Muslims, and shortly thereafter, in ones by Jews. Although most of the traditions had to do with the Tabernacle, some traditions started to identify Shiloh with the tomb of Eli and his family. The present study looks at the relationship between the practice of ziyara (“visit” in Arabic), which was characterized by the veneration of tombs, and the cult in Shiloh. The paper also surveys archeological finds in Shiloh that attest to a medieval cult and compares them with the written sources. In addition, it presents testimonies by Christians about Jewish cultic practices, along with testimonies about the cult place shared by Muslims and Jews in Shiloh. Examination of the medieval cult in Shiloh provides a broader perspective on an uninstitutionalized regional cult. Keywords: Shiloh; medieval period; Muslim archeology; travelers 1. Introduction Maintaining the continuous sanctity of a site over historical periods, and even between different faiths, is a well-known phenomenon: It is a well-known phenomenon that places of pilgrimage maintain their sacred status even after shifts in the owners’ faith (Limor 1998, p. -

Eli Smith and the Arabic Bible

ELI SMITH AND THE ARABIC BIBLE YALE DIVINITY SCHOOL LIBRARY OccasionalPublication, No. 4 YALE DIVINITY SCHOOL LIBRARY OccasionalPublication, No. 4 ELI SMITH AND THE ARABIC BIBLE by Margaret R. Leavy NEW HA VEN, CONNECTICUT 1993 TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction 1 Eli Smith and the Arabic Bible The A.B.C.F.M. Press in Malta 7 The Press in Beirut - A New Arabic Type 11 The Bible in Arabic 14 Note on Sources 22 Appendix: Eli Smith on the Difficulties of Translating 23 an Arabic Grammar: From a letter to Moses Stuart, reprinted in the Biblical Repository,vol. 2, January, 1832. Introduction This essay by Margaret R. Leavy was. commissioned to mark·the opening of two exhibits at the Yale Divinity School Library.: "Missionary Translators" and "The, Yale Missionary Bible Cpllection." Thes,e exhibits, prepared tO' G<>incidewith a symposium entitled LANGUAGE, CULTl.J!IB'AND TRANSLATION:·FURTHER: STUDIES :·IN THE MISSIONARYMOVEMENl', described the lives and werk of. various missionary translators and displayed products of their labors. Recent scholarsqip has drawn attention to the impact of Bible transJation on the social and cultural'{ievelopment of societies. Lamin.Sanneh, for e~ample, has pointed to the "connections between Bible· translatiqg· and related issues such as cultural self understanding·, vernacular pride~ ,social awakening, religious renewal'; cross-qultural dialogue, transmission and recipiency, reciprocity in mission~, .. "1 IA. his work Translatingthe Message:.The MissionaryImpact on -Culture,.Sannenfurther notes that: Tlie distinguishing mark of scriptural translation has been the effort to <;ome.as close as possible to the speech of the common people. Translators have consequently first de~oted much time, effort, and resources to building the basis, with investigations into the culture, history, language, religion, economy, anthropolo~y, and physical environment of the peoI?le concerned, before tackling tlteir 'concrete task. -

Op7 Smalley Duffy 2003.Pdf

GUIDE TO ARCHIVES AND MANUSCRIPT COLLECTIONS AT THE YALE DIVINITY SCHOOL LIBRARY YALE DIVINITY SCHOOL LIBRARY Occasional Publication No. 7, Third Edition YALE DIVINITY SCHOOL LIBRARY Occasional Publication No. 7 GUIDE TO ARCHIVES AND MANUSCRIPT COLLECTIONS AT THE YALE DIVINITY SCHOOL LIBRARY Compiled by Martha Lund Smalley Joan R. Duffy NEW HA VEN, CONNECTICUT Yale Divinity School Library Revised edition 2003 TABLE OF CONTENTS Page INTRODUCTION I PERSONAL PAPERS 2 ARCHIVES OF ORGANIZA TIONS 42 Geographical listing 50 List of abbreviations 52 The Occasional Publications of the Yale Divinity School Library are sponsored by The George Edward and Olivia Hotchkiss Day Associates INTRODUCTION Special Collections at the Yale Divinity School Library Special Collections at the Yale Divinity School Library ipclude more than 3000 linear feet of archival and manuscript material, extensive'archivat material in microform fdrll\at, and numerous i1,1dividuallycataloged manuscripts. Holdings include personal and organizational papers, reports, pamphlets, and ephemera related to various aspects ofreligious history. Particular strengths of the collection are its documentation of the Protes tant missionary endeavor, its records related to American clergy and evangelists, and its documentation of religious work among college and university students. The Divinity Library collection includes personal papers of numerous faculty members and deans, and ephemeral material related to life at the Divinity School; official archives of the Divinity School are deposited in the Yale University Archives. Parameters of this guide This guide lists selected personal papers and organizational archives held at the library. The guide lists both material held {n its original format, and micro~orm colle~tions of archives apd personal papers heJ.delse'Yhere. -

Henrietta Butler Smith Collection, 1827-1995

Archives and Special Collections Department, American University of Beirut Beirut, Lebanon © 2018 Henrietta Butler Smith Collection, 1827-1995 A Finding Aid to the Collection in the University Libraries, AUB Prepared by Iman Abdallah Abu Nader Contact information: [email protected] Webpage: www.aub.edu.lb/libraries/asc Descriptive Summary Call No: AA: 7.5 Bib record: b22071908 Record Creator: Henrietta "Hetty" Simpkins Butler Smith. Collection Title: Henrietta Butler Smith Collection, 1827-1995. Collection Dates: 1827-1995 Physical Description: 2 boxes (1 linear foot) Language(s): English Administrative Information Source: The Collection was bought from a vendor in the States during the summer 2018. Access Restrictions: The collection can be used within the premises of the Archives and Special Collections Department, Jafet Memorial Library, American University of Beirut. Photocopying Restriction: No photocopying restriction except for fragile material. Preferred Citation Henrietta Butler Smith Collection, 1827-1995: Box no., File no., American University of Beirut/Library Archives. Scope and Content Correspondence of the family of Mrs. Henrietta "Hetty" S. Butler Smith, wife of Missionary Reverend Eli Smith. The collection contains approximately 145 letters, including around 92 letters written by Ms. Smith to her two sons, Edward “Ned” Robinson Smith (artist), and Benjamin Eli Smith (editor of the Century Dictionary); 11 letters written by Benjamin Eli Smith to his mother when he was studying in Germany, in addition to letters from Sarah Smith to her mother Hetty Smith, and other letters, ephemera & photos. Dates of the documents range from 1827-1995. Arrangement This collection is arranged in five series: Series I: Correspondence Series II: Ephemera Series III: Photos Series IV: Postcards Series V: Handwritten and printed Publications Biographical Sketch Henrietta "Hetty" Simpkins Butler Smith (1815-1893) Henrietta Simpkins Butler was born in 1815 in Northampton, MA. -

The Reminiscences of Daniel Bliss

351 S 81 B64 ^0" 'Sp \ )l.fN LIBR \KY Cornell University Library LG 351.S81B64 The reminiscences of Daniel Bliss, 3 1924 011 492 463 DATE DUE ABJhffT Cornell University Library The original of tliis book is in tine Cornell University Library. There are no known copyright restrictions in the United States on the use of the text. http://www.archive.org/details/cu31924011492463 Daniel Bliss in His Seventieth Year. The Reminiscences of Daniel Bliss Edited and Supplemented by His Eldest Son iUUSIRATSa New York Chicago Fleming H. Reveil Company London and Edinburgh 'f':''" Copyright, 1920, by FLEMING H. REVELL COMPANY Ay f30 New York: i$8 Fifth Avenue Chicago': 17 North Wabash Ave. London : ai Paternoster Square Edinburgh : 75 Princes Street Dedicated to ALL HIS STUDENTS ' s '^ 00 ^ 35: I I Q 0iUl o CO > m z o Q o m Q z D o fl) n r ^C > pj m 00 111 CL r o S ^ 2 Illustrations Facingpage Daniel Bliss in His Seventieth Year . Title President Bliss and President Washburn . 60 Dr. and Mrs. Bliss . ... 80 The Young Missionary 130 Marquand House: The President's Residence . 188 Statue Presented to the College by Graduates and Former Students in Egypt and the Sudan . 220 President Howard Sweetser Bliss .... 230 At the College Gate . < \ . 240 The Ninetieth Birthday : Dr. Bliss with His Grcat- Grandchildren . • • ^ . 252 I EDITOR'S INTRODUCTION UNITY is the distinctive mark of the life- work of Daniel Bliss. He was born on August 17, 1823, and lived to within a few days of his ninety-third birthday, passing peace- fully away, not in any illness, but because his time had come, on July 27, 1916, at his home in Beirftt, Syria.