The Ethics Centre

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Clean Energy Transition

Leadership Forum on energy transition Forum Member Profiles Professor Ian Jacobs (Chair) President and Vice-Chancellor, UNSW Australia Ian came to Australia from the UK, where he had a distinguished career as a leading researcher in the area of women’s health and cancer, and in university leadership. Immediately prior to joining UNSW Ian was Vice President and Dean at the University of Manchester and Director of the Manchester Academic Health Science Centre, a partnership linking the University with six healthcare organisations involving over 36,000 staff. Ian is the Principal Investigator for the Cancer Research UK and Eve Appeal funded PROMISE (Prediction of Risk of Ovarian Malignancy Screening and Early Detection) programme and on several large multicentre clinical trials including the UK Collaborative Trial of Ovarian Cancer and the UK Familial Ovarian Cancer Screening Study. Ian established and chairs the Uganda Women’s Health Initiative, is founder and Medical Advisor to the Eve Appeal charity, a Patron of Safehands for Mothers, founder and non- Executive Director of Abcodia Ltd and patent holder of the ROCA (Risk of Ovarian Cancer Algorithm). Mr Geoffrey Cousins AM President, Australian Conservation Foundation Geoff is an Australian community leader, businessman, environmental activist and writer. As an environmental activist he is best known for his successful campaigns to stop the Gunns pulp mill in Tasmania and the proposed Woodside gas hub in the Kimberley. Geoff’s distinguished business career has included Chief Executive roles in advertising and media and positions on a number of public company boards including PBL, the Seven Network, Hoyts Cinemas group, NM Rothschild & Sons Limited and Telstra. -

It's Just a Joke: Defining and Defending (Musical) Parody

It’s just a joke: Defining and defending (musical) parody Paul Jewell, Flinders University Jennie Louise, The University of Adelaide ABSTRACT Australia has recently amended copyright laws in order to exempt and protect parodies, so that, as the Hon. Chris Ellison, the then Minster for Justice told the Senate, ‘Australia’s fine tradition of poking fun at itself and others will not be unnecessarily restricted’. It is predicted that there will be legal debates about the definition of parody. But if the law, as the Minister contends, reflects Australian values, then there is a precursor question. Is there anything wrong with parody, such that it should be restricted? In our efforts to define parody, we discover and develop a moral defence of parody. Parody is the imitation of an artistic work, sometimes for the sake of ridicule, or perhaps as a vehicle to make a criticism or comment. It is the appropriation of another’s original work, and therefore, prima facie, exploits the originator. Parody is the unauthorised use of intellectual property, with both similarity to and difference from other misappropriations such as piracy, plagiarism and forgery. Nevertheless, we argue that unlike piracy, plagiarism and forgery, which are inherently immoral, parody is not. On the contrary, parody makes a positive contribution to culture and even to the original artists whose work is parodied. Paul Jewell <[email protected]> is a member of the Ethics Centre of South Australia. He teaches ethics in Disability and Community Inclusion at Flinders University and he is a musician. Jennie Louise is also a member of the Ethics Centre of South Australia. -

Business Ethics Study

The 2009 Annual Business and Professions Study business ethics study St James Ethics Centre Beaton Consulting 2009 Annual Business and Professions Study: Business Ethics Study Foreword This report has been produced at a pivotal point in history. The global community is faced by a conjunction of challenges so grave as to justify being considered ‘crises’. The list includes some obvious issues – climate change caused by global warming, world-wide recession, a global food crisis affecting the most vulnerable. However, there is something less obvious that we should attend to - there is also a crisis of confidence; in our principal institutions, their legitimacy and their leadership. Until this deeper issue is acknowledged and addressed our latent capacity to resolve the more obvious issues will falter for want of conviction. Barack Obama sought to identify one dimension of this deeper problem when, prior to his inauguration as President, he sought to indentify the principal factors that had brought the US economy to its knees. This crisis did not happen solely by some accident of history or normal turn of the business cycle, and we won’t get out of it by simply waiting for a better day to come, or relying on the worn-out dogmas of the past. We arrived at this point due to an era of profound irresponsibility that stretched from corporate boardrooms to the halls of power in Washington, DC. For years, too many Wall Street executives made imprudent and dangerous decisions, seeking profits with too little regard for risk, too little regulatory scrutiny, and too little accountability. -

Australian Ethics

AUSTRALIAN ETHICS DECEMBER 2013 AUSTRALIAN APPLIED ETHICS PRESIDENT’S REPORT ASSOCIAITON FOR PROFSSIONAL AND ETHICAL REFLECTIONS E T H I C S : O N MEANNESS APPLIED AND Hugh Breakey PROFESSIONAL Business Meanness is a common occurrence. It ‘contempt’ and ‘cruelty’. Even here, his forms part of the social backdrop in Education treatment is revealing. Hobbes holds which we all live, play and work. Most Engineering that these emotions arise from being of us, I think, can think of examples of Environment insensible to others’ calamities—an mean behaviour we have witnessed, Law insensitivity he thinks proceeds from and many of us would know someone Medical one’s own security. For Hobbes does we think of as ‘having a mean streak’. not conceive it possible ‘that any man Nursing should take pleasure in other men’s Police Yet meanness is not a topic that gar- great harms’ purely for its own sake. Public Policy ners much ethical attention. Out of As I read him, Hobbes first tries to pre- Public Sector curiosity, I recently searched a few academic databases for works on sent cruelty as an instance of insensi- Social Work meanness. Even in the context of psy- tivity (which it is not), and then tries to Teaching chology there was surprisingly little— confect ‘ends’ being served by the cru- most of it about school-age children. elty, so as to deny the possibility—the INSIDE THIS I S- In terms of philosophical or ethical very conceivability—of someone inflict- SUE: analysis, there was almost nothing. ing harm for the sheer pleasure of it. -

Learn Everything That Facebook Knows About You

Intelligent Robots To Power China’s Factories As a Technocracy, China seeks maximum efficiency and maximum human displacement. The policies, coupled with draconian social engineering, is anti-human as it eliminates human values and dignity. ⁃ TN Editor Robots powered by artificial intelligence are set to replace Chinese factory workers in a move aimed at boosting the manufacturing industry which has been hit hard by a rise in wages. The machines which are capable of making, assembling and inspecting goods on production lines have already been rolled out, with one factory laying off 30 workers to make way for the robots. The robots were displayed at China’s Hi-Tech fair in Shenzhen earlier this month, an annual event which showcases new development ideas with the aim of driving growth in a number industries. But the news has annoyed Washington as it is expected to put international competitors at a disadvantage, as the two countries’s bitter trade war continues to escalate. Speaking to the Financial Times, Sabrina Li, a senior manager at IngDan, said: “We incubated this platform so we can meet the (Made in China 2025) policy. “One noodle factory was able to dismiss 30 people, making it more productive and efficient.” Giving the suffering manufacturing industry a leg up is a key part of the Chinese government’s Made in China 2025 policy. Zhangli Xing, deputy manager of Suzhou Govian Technology which sells the quality control robots, said they are more reliable than human labour. Mr Xing said : “A person looking by eye would take 5-6 seconds for each object, versus 2-3 seconds by machine. -

38.3. Ethics and Professional Practice

Ethics and Professional Practice Core Body of Knowledge for the Generalist OHS Professional Second Edition, 2019 38.3 February 2019 Copyright notice and licence terms Copyright (2019) Australian Institute of Health & Safety (AIHS), Tullamarine, Victoria, Australia This work is copyright and has been published by the Australian Institute of Health & Safety (AIHS). Except as may be expressly provided by law and subject to the conditions prescribed in the Copyright Act 1968 (Commonwealth of Australia), or as expressly permitted below, no part of the work may in any form or by any means (electronic, mechanical, microcopying, digital scanning, photocopying, recording or otherwise) be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted without prior written permission of the AIHS. You are free to reproduce the material for reasonable personal, or in-house, non-commercial use for the purposes of workplace health and safety as long as you attribute the work using the citation guidelines below and do not charge fees directly or indirectly for use of the material. You must not change any part of the work or remove any part of this copyright notice, licence terms and disclaimer below. A further licence will be required and may be granted by the AIHS for use of the materials if you wish to: • reproduce multiple copies of the work or any part of it • charge others directly or indirectly for access to the materials • include all or part of the materials in advertising of a product or services or in a product for sale • modify the materials in any form, or • publish the materials. -

Principles for Good Technology

THE ETHICS CENTRE ETHICAL BY DESIGN: PRINCIPLES FOR GOOD TECHNOLOGY DR MATTHEW BEARD & DR SIMON LONGSTAFF AO T. E. C. H. N. I. C. A. L. M. A. S. T. E. R. Y. D. I. V. O. R. C. E. D. F. R. O. M. E. T. H. I. C. A. L. R. E. S. T. R. A. I. N. T. I. S. A. T. T. H. E. R. O. O. T. O. F. A. L. L. T. Y. R. A. N. N. Y. .. 2 THE ETHICS CENTRE 3 PR00. OUGHT BEFORE CAN PR04. NET BENEFIT The fact that we can do something does not mean that we should. Maximise good, minimise bad. There are lots of possible worlds out there – lots of things that could be made or built. The things we build should make a positive contribution to the world – they should Ethical design is about ensuring what we build helps create the best possible world. make it better. But more than this, we should also be mindful of the potentially harmful Before we ask whether it’s possible to build something, we need to ask why we would side-effects of our technology. Even if it does more good than bad, ethical design want to build it at all. requires us to reduce the negative effects as much as possible. PR01. NON-INSTRUMENTALISM PR05. FAIRNESS Never design technology in which people are merely a part of the machine. Treat like cases in a like manner; different cases differently. Some things matter in ways that can’t be measured or reduced to their utility value. -

The Social CEO

The social CEO Keynote speaker: Alison Watkins, Group Managing Director, Coca-Cola Amatil Friday, 22 March 2019, 12 pm to 2 pm Four Seasons Hotel, Sydney www.ceda.com.au agenda 11.45am Registrations 12.00pm Welcome Lee Kelly State Director NSW/ACT, CEDA 12.05pm Introduction Narelle Hooper Editor-in-Chief, Company Director Magazine, Australian Institute of Company Directors 12.10pm Keynote address Alison Watkins Group Managing Director, Coca-Cola Amatil 12.30pm Lunch 1.00pm Moderated discussion Debby Blakey Chief Executive Officer, HESTA Nik Gowing Founder and Co-Director, Thinking the Unthinkable project; Former BBC presenter Narelle Hooper Editor-in-Chief, Company Director Magazine, Australian Institute of Company Directors Steven Spurr Chief Executive Officer, Edelman Alison Watkins Group Managing Director, Coca-Cola Amatil 1.40pm Q&A session 1.55pm Vote of thanks Megan Motto Chief Executive Officer, Governance Institute of Australia 2.00pm Close keynote speaker Alison Watkins Group Managing Director, Coca-Cola Amatil Twitter: @cocacolaamatil Alison joined Coca-Cola Amatil as Group Managing Director in March 2014. Alison is a non-executive director of The Centre for Independent Studies and the Business Council of Australia. Alison’s previous roles include Chief Executive Officer of agribusiness GrainCorp Limited and of Berri Limited, the market leader in Australian juice, and Managing Director of Regional Banking at ANZ. Alison spent 10 years at McKinsey & Company from 1989-1999 and became a partner of the Firm in 1996 before moving to ANZ as Group General Manager Strategy. Alison has been a non- executive director of Australia and New Zealand Banking Group Limited, Woolworths Limited and Just Group Limited. -

Ethics in the Boardroom

Ethics in the Boardroom A decision-making guide for directors October 2019 ETHICS IN THE BOARDROOM Purpose of this guide This document has been developed as a guide to Link to additional resources ethical decision-making in the boardroom. Rather · Governing organisational culture. The than focus on the ethical obligations of directors, AICD’s practical tool to help shape it aims to support directors as they navigate the the board’s approach to culture. complex ethical terrain that is encountered in The tool can be found at aicd. every boardroom. This guide does not attempt to prescribe a set of rules for good conduct. companydirectors.com.au/culture. Instead, it aims to complement and inform the · For directors seeking assistance with good judgement that directors bring to their a specific ethical dilemma, The Ethics deliberations. Centre offers the Ethi-call service. The insights that are presented in this document Ethi-call is a free, independent, have been distilled from interviews and roundtable national helpline available to all. discussions with experienced directors and subject It provides expert and impartial matter experts, including senior academics and guidance in relation to ethical issues. board advisers. To book a call, visit the website at The focus of this document is the boardroom; ethics.org.au/initiatives/ethi-call/. the ultimate source of the ethical tone that flows · Membership of The Ethics Centre’s throughout a well-governed organisation. corporate program The Ethics This guide can be used: Alliance unlocks access to The Ethics Centre’s sophisticated decision- · as a general resource for directors; making tool FieldKit. -

Silencing and Censorship in the Transgender Rights Debate Edit

SILENCING AND CENSORSHIP IN THE TRANSGENDER RIGHTS DEBATE The recent launch of the group Transforming Tasmania, which aims to lobby for law reforms that improve the lives of transgender and gender- diverse people, is an opportunity for the community to engage in robust, open and safe discussions on matters concerning gender identity. The media has an important role to play in such discussions, and needs to actively encourage the expression of diverse viewpoints. Tasmanian media organisations could follow the example set by prominent UK publication, The Economist - https://www.economist.com/transgender - and invite individuals holding a range of opinions on transgenderism and transgender identities to express their ideas in writing in a dedicated forum. It’s a challenge, and one that media players should have the intestinal fortitude to accept, with all the alacrity expected of dedicated members of the Fourth Estate. OVERVIEW Identity politics is becoming an increasingly controversial topic especially within women spaces, schools, sports clubs, universities and the LGBTQI community. Since 2012 in Tasmania, a number of examples of bullying, threats and intimidation by trans activists against people with different points of view have been brought to light in the media. Until now, several other cases have not been reported. This article will outline those cases and also provide a broad introduction to media reports on no-platforming and censorship at universities, proposed changes to anti-discrimination laws, and acts of silencing and intimidation against critics of trans rights tactics and campaigns. SUPPRESSING DEBATE Australian feminist activist and scholar Germaine Greer, while stating that transgenderism is not her issue, has been repeatedly targeted by the trans rights movement with attempts to have her no-platformed and banned from speaking at universities because of her views on 1 transgenderism. -

Attachment A

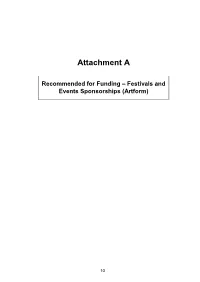

Attachment A Recommended for Funding – Festivals and Events Sponsorships (Artform) 10 Festivals and Events Sponsorship (Artform) 2019-20 Round 2 Recommended for Funding Festivals and Events Sponsorship (Artform) 2019-20 Round 2 Organisation Project Name Project Description $ Amount VIK Requested $ Amount VIK Conditions Name Requested Recommended Recommended RECOMMENDED FOR FUNDING Apocalypse La Femme A series of neo-burlesque $9,540 Nil $9,540 Nil Nil Theatre Company shows featuring local Incorporated performers at the Vanguard in Newtown exploring the representation of femme identities in popular culture and informed by Sydney icons and modern Australian narrative. 11 Audiocraft Pty Ltd Audiocraft Podcast A three day podcasting $26,500 Nil $20,000 Nil Nil Festival festival at the Australian Film, Television and Radio School in Moore Park bringing together podcast producers for skills development, networking and knowledge sharing. Festivals and Events Sponsorship (Artform) 2019-20 Round 2 Organisation Project Name Project Description $ Amount VIK Requested $ Amount VIK Conditions Name Requested Recommended Recommended RECOMMENDED FOR FUNDING Australian Art Art Month Sydney A contemporary art $18,000 Street Banner $18,000 Street Banner Nil hire fee waiver to Events Foundation 2020 festival featuring Hire fee waiver exhibitions, talks, walking to the value of the value of and cycling tours, and $9,272 $9,272 workshops in Chippendale, East Sydney and Paddington with precinct activations through Waterloo, Green Square, and Newtown. Comedy Sydney Comedy A series of comedy Nil Venue Hire fee Nil Venue Hire fee Nil waiver to the Development Ltd Festival at Sydney events held at Sydney waiver to the Town Hall Town Hall placing special value of $26,475 value of $26,475 focus on children, families, emerging artist Street Banner Street Banner development and Hire fee waiver hire fee waiver to attracting new audiences to the value of the value of 12 through innovative and $9,798 $9,798 accessible programming. -

State of Reconciliation Discussion Guide Contents

STATE OF RECONCILIATION DISCUSSION GUIDE CONTENTS How to Engage with this Guide 3 4. UNITY 29 Let’s Talk: Unity 30 1. RACE RELATIONS 4 Unpacking and Understanding the Dimension 30 Let’s Talk: Race Relations 5 Quick Stats 31 Unpacking and Understanding the Dimension 5 Let’s Walk: Unity 34 Discussion Questions and Activities 6 Case study: Yabun Festival, Share the Spirit Quick Stats 6 Festival and Survival Days 34 Case study: The Marruk Project 34 Let’s Walk: Race Relations 10 Ideas for Action 35 Case study: The Freedom Ride 10 References 36 Case study: Joint Statement on Racism directed at Adam Goodes 10 5. HISTORICAL ACCEPTANCE 37 Ideas for Action 11 References 12 Let’s Talk: Historical Acceptance 38 Unpacking and Understanding the Dimension 38 2. EQUALITY & EQUITY 13 Quick Stats 39 Let’s Talk: Equality and Equity 14 Let’s walk: Historical Acceptance 41 Unpacking and Understanding the Dimension 14 Case study: Myall Creek Memorial 41 Discussion Questions and Activities 16 Case study: Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Quick Stats 16 Histories and Cultures 41 Ideas for Action 42 Let’s Walk: Equality and Equity 18 References 43 Case study: The Wave Hill Walk-Off 18 Case study: Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Soldiers 18 The State of Reconciliation in Australia 44 Ideas for Action 19 About Reconciliation Australia 45 References 20 Annual Days and Weeks of National Significance to Reconciliation in Australia 46 3. INSTITUTIONAL INTEGRITY 21 Let’s Talk: Institutional Integrity 22 Reconciliation Timeline 48 Unpacking and Understanding the Dimension 22 Quick Stats 23 Let’s walk: Institutional Integrity 26 Case study: Glenelg Aboriginal Partnership Agreement, 2011-2020 26 Case study: Muntjiltjarra Wurrgumu Group 26 Ideas for Action 27 References 28 2 HOW TO ENGAGE WITH THIS GUIDE This guide has been compiled as a simplified summary of Reconciliation Australia’s landmark State of Reconciliation in Australia report (2016).