Parody and Pastiche Images of the American Revolution

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Adversaries in a Cauldron

c01.qxd 09/29/03 11:15 AM Page 1 One Adversaries in a Cauldron On Broadway across from Bowling Green in New York City, Benedict Arnold, American turncoat and now a brigadier general in His Majesty’s Royal British Army, limped into British army headquarters. It was late November 1780. Arnold had been summoned by Sir Henry Clinton, fifty, command- ing general of the British forces in North America, to get his marching orders for a new attack on the rebels. This was to be Arnold’s first action against his former compatriots, and he had been urging Clinton to let him attack Philadelphia, a storehouse for vast quantities of military sup- plies and also the seat of the Continental Congress—those dozens of gallows-bait revolutionists whom Arnold hated so passionately. Such a military strike could entomb the revolution. Clinton had declined. Arnold then urged an attack in one of the southern states. Clinton had taken time to think it over. General Clinton was squirming in a military and political cauldron. Nearly six years after the American Revolution had begun, the British army seemed no closer to defeating the rebels. In fact, for two and a half years, since the Battle of Monmouth in New Jersey, George Washington and his ragged band of starvelings had been waiting a few miles north on the Hudson highlands for Sir Henry to come out of his New York fortress to challenge them again on the battlefield. The two men sitting here across from each other were the very yin and yang of personalities: phlegmatic Sir Henry, the ever-planning, cau- tious, slow-to-move British career soldier; and mercurial Arnold, the ever- dangerous, explosive, militarily gifted Connecticut soldier, a legend even among British officers. -

132 Portraits by Gilbert Stuart. in 1914

132 Portraits by Gilbert Stuart. PORTRAITS BY GILBERT STUART NOT INCLUDED IN PREVIOUS CATALOGUES OF HIS WORKS. BY MANTLE FIELDING. In 1914 the '' Pennsylvania Magazine of History and Biography" published a list of portraits painted by Gilbert Stuart, not mentioned in the "Life and Works of Gilbert Stuart" by George C. Mason. In 1920 this was followed in the same periodical by "Addenda and Corrections" to the first list, in all adding about one hundred and eighty portraits to the original pub- lication. This was followed in 1926 by the descriptive cata- logue of Stuart's work by the late Laurence Park, which noted many additions that up to that time had eluded the collectors' notice. In the last two years there have come to America a number of Stuart por- traits which were painted in England and Ireland and practically unknown here before. As a rule they differ in treatment and technique from his work in America and are reminiscent more or less of the English school. Many of these portraits lack some of the freedom and spirit of his American work having the more careful finish and texture of Eomney and Gainsborough. These paintings of Gil- bert Stuart made during his residence in England and Ireland possess a great charm like all the work of this talented painter and are now being much sought after by collectors in this country. No catalogue of the works of an early painter, how- ever, can be called complete or infallible and in the case of Gilbert Stuart there seems to be good reason to believe that there are still many of his portraits in Portraits by Gilbert Stuart. -

Deshler-Morris House

DESHLER-MORRIS HOUSE Part of Independence National Historical Park, Pennsylvania Sir William Howe YELLOW FEVER in the NATION'S CAPITAL DAVID DESHLER'S ELEGANT HOUSE In 1790 the Federal Government moved from New York to Philadelphia, in time for the final session of Germantown was 90 years in the making when the First Congress under the Constitution. To an David Deshler in 1772 chose an "airy, high situation, already overflowing commercial metropolis were added commanding an agreeable prospect of the adjoining the offices of Congress and the executive departments, country" for his new residence. The site lay in the while an expanding State government took whatever center of a straggling village whose German-speaking other space could be found. A colony of diplomats inhabitants combined farming with handicraft for a and assorted petitioners of Congress clustered around livelihood. They sold their produce in Philadelphia, the new center of government. but sent their linen, wool stockings, and leatherwork Late in the summer of 1793 yellow fever struck and to more distant markets. For decades the town put a "strange and melancholy . mask on the once had enjoyed a reputation conferred by the civilizing carefree face of a thriving city." Fortunately, Congress influence of Christopher Sower's German-language was out of session. The Supreme Court met for a press. single day in August and adjourned without trying a Germantown's comfortable upland location, not far case of importance. The executive branch stayed in from fast-growing Philadelphia, had long attracted town only through the first days of September. Secre families of means. -

Levi's Life After the Revolutionary

This book is dedicated to Crystal Farish, Hauley Farish, Lane Farish, Brooke Barker, Heidi Thornton, Justin Thornton, Anthony Thornton, and Jasmine Parker, all of whom are the 5th-great-grandchildren of Levi Temple. THE AMAZING LIFE OF 1751–1821 ii TABLE OF CONTENTS LEVI TEMPLE’S DESCENdaNTS . iv THE LIFE OF LEVI TEMPLE . 1 LEVI’S LIFE BEFORE THE WAR . 3 THE BOSTON MASSacRE . 7 THE BOSTON TEA PARTY . 8 THE MINUTEMEN . 10 THE BattlE OF BUNKER HILL . 12 THE LIFE OF A PatRIOT SOLDIER . 14 LIFE at HOME DURING THE WAR . 18 THE DECLARatION OF INDEPENDENCE . 20 THE BRITISH SURRENDER at YORKTOWN . 22 THE TREatY OF PARIS . 24 LEVI’S LIFE AFTER THE REVOLUTIONARY WAR . 26 LEVI’S LEGacY . 28 ENDNOTES . 30 iii Thirteen stars represent the original colonies in this Revolutionary War flag. Richard S. Farish Crystal Lee 1940 ~ 1971 Farish Harwood Dean 1959 ~ Living Thornton Levi Georgia Flo 1918 ~ 1966 Temple Thornton Levi Phillip John Temple 1751 ~ 1821 1943 ~ 2006 Dawe Job 1788 ~ 1849 Bette Lee 1896 ~ 1970 Temple Dawe Rachel Solomon David 1811 ~ 1888 Nutting 1921 ~ 1984 Temple Lucy Georgia Annabelle 1856 ~ 1915 Brown 1752 ~ 1830 Temple Isabella abt. 1798 ~ 1852 1895 ~ 1955 Robertson Flora W. 1831 ~ 1880 Forbes 1862 ~ 1948 iviv The Life of Levi Temple our ancestor, Levi Temple, was one of many everything they owned, ruin their families, and risk YAmerican colonists who risked his life to win suffering the undignified death of a traitor. freedom from British rule. This brave decision helped Courage and determination allowed the Patriots make the United States of America a reality, but it also to overcome incredible odds. -

Anthony, Albro, 209 Anthony, Elizabeth, 133, 209, 210

INDEX (Family surnames of value in genealogical research are printed in CAPITALS; names of places in italics Abell, John, to Humphry Marshall, ANTHONY, MICHAEL, 211 277 ANTHONY, SUSAN, 209 Aehey, Herman, 333 ANTHONY, THOMAS, 211 Achey, Jacob, 333 Antietam, Battle of, 31, 33, 39, 50 ; Adams, Charles Francis, 43 statistics of troops at, 48 Adams, John, 354 ; on advantages of Appleton, John, 73, 74 reprisals, 352 Archer, Capt. Thomas, 125 Adams, Robert, 293 Arent, Col. Baron, 239 Akin, James, engraver, 229; bio- Armistead, Gen. Lewis Addison, 4 graphical, 216 ARMSTRONG, GEORGE, 198, 199 ALBERT, MRS. JOHN SEAMAN, 298 ARMSTRONG, RACHEL, 198, 199 ALBRO, JOHN, 133 ARMSTRONG, THOMAS, 198, 199 Alden, John, 311 Asbury, Francis, 314 Alert, The, 365 Ashmead, Samuel, certificate of Oath Alexander, Gen., 44 of Allegiance of, 1777, 226 Alfred, The, 374 ASHTON, JANE, 300, 303 Allen, • • 343, 367 Assembly of Pennsylvania, 153-157 Allen, John, 348 ASSHETON, FRANCES, 295 ALLEN, MARTHA, 10, 13 ASSHETON, MARGARET, 296, 297 ALLEN, MARY, 10 ASSHETON, ROBERT, 295, 296, 297 ALLEN, NATHANIEL, 194, 195 ASSHETON, WILLIAM, 295 Allen, Nathaniel, Commissioner for Associated Militia Cavalry, 376 Colony of Pennsylvania, 127, 129 Audubon, James J., 335 ALLEN, NEHEMIAH, 194 Austin, Hon. James T., 135 ALLEN, PRISCILLA, 12, 13 Azilum, colony for French refugees, ALLEN, REBECCA BLACKFAN, 194 335, 336, 340 ALLEN, SAMUEL, 10 Allen, Sergeant Samuel, 376 Babson, Captain, 368 American Blues, 379 Bache, Benjamin Franklin, 382 American Magazine and Monthly BAILEY, ABIGAIL, 381 Chronicle for the British Colonies, BAILEY, FRANCIS, 381 edited by a "Society of Gentle- Baker, Maj. Chalklay S., 381 men," 343; printed by William Baker & Abell, to Humphry Marshall, Bradford, 343 ; poem signed Love- 272 lace published in 1758, 344; an- Balch, Thomas, 343 notated volume of, in British Mu- BALLIET, PAUL, 332 seum, 346, 347; verses in signed Baltimore, Lord, 128 F. -

You Are Viewing an Archived Copy from the New Jersey State Library for THREE CENTU IES PEOPLE/ PURPOSE / PROGRESS

You are Viewing an Archived Copy from the New Jersey State Library FOR THREE CENTU IES PEOPLE/ PURPOSE / PROGRESS Design/layout: Howard Goldstein You are Viewing an Archived Copy from the New Jersey State Library THE NEW JERSE~ TERCENTENARY 1664-1964 REPORT OF THE NEW JERSEY TERCENTENA'RY COMM,ISSION Trenton 1966 You are Viewing an Archived Copy from the New Jersey State Library You are Viewing an Archived Copy from the New Jersey State Library STATE OF NEW .JERSEY TERCENTENARY COMMISSION D~ 1664-1964 / For Three CenturieJ People PmpoJe ProgreJs Richard J. Hughes Governor STATE HOUSE, TRENTON EXPORT 2-2131, EXTENSION 300 December 1, 1966 His Excellency Covernor Richard J. Hughes and the Honorable Members of the Senate and General Assembly of the State of New Jersey: I have the honor to transmit to you herewith the Report of the State of New Jersey Tercentenary Commission. This report describee the activities of the Commission from its establishment on June 24, 1958 to the completion of its work on December 31, 1964. It was the task of the Commission to organize a program of events that Would appropriately commemorate the three hundredth anniversary of the founding of New Jersey in 1664. I believe this report will show that the Commission effectively met its responsibility, and that the ~ercentenary obs~rvance instilled in the people of our state a renewfd spirit of pride in the New Jersey heritage. It is particularly gratifying to the Commission that the idea of the Tercentenary caught the imagination of so large a proportior. of New Jersey's citizens, inspiring many thousands of persons, young and old, to volunteer their efforts. -

A Closer Look at James and Dolley Madison Compiled by the National Portrait Gallery, Smithsonian Institution

A Closer Look at James and Dolley Madison Compiled by the National Portrait Gallery, Smithsonian Institution Target Grade Level: 4–12 in United States history classes Objectives After completing this lesson, students will be better able to: • Identify and analyze key components of a portrait and relate visual elements to relevant historical context and significance • Compare and contrast the characteristics of two portraits that share similar subject matter, historical periods, and/or cultural context • Use portrait analysis to deepen their understanding of James and Dolley Madison and the roles that they played in U.S. history. Portraits James Madison by Gilbert Stuart Oil on canvas, 1804 The Colonial Williamsburg Foundation, Virginia Dolley Madison by Gilbert Stuart Oil on canvas, 1804 White House Collection, Washington, D.C.; gift of the Walter H. & Phyllis Shorenstein Foundation in memory of Phyllis J. Shorenstein Additional Artworks For more portraits and artworks, visit the “1812: A Nation Emerges” online exhibition at http://npg.si.edu/exhibit/1812 Background Information for Teachers Information about James Madison (1751–1836) from the James Madison Museum (http://www.thejamesmadisonmuseum.org/biographies/james-madison) James Madison was born on March 16, 1751, in Port Conway, Virginia. The oldest of ten children in a distinguished planter family, he was educated by tutors and at Princeton University (then called the College of New Jersey). At a young age, Madison decided on a life in politics. He threw himself enthusiastically into the independence movement, serving on the local Committee of Safety and in the Virginia Convention, where he demonstrated his abilities for constitution-writing by framing his state constitution. -

Portraits by Gilbert Stuart

PORTRAITS BY JUNE 29 TO AUGUST l • 1936 AT THE GALLERIES OF M. KNOEDLER & COMPANY NEWPORT RHODE ISLAND As A contribution to the Newport Tercentenary observation we feel that in no way can we make a more fitting offering than by holding an exhibition of paintings by Gilbert Stuart. Nar- ragansett was the birthplace and boyhood home of America's greatest artist and a Newport celebration would be grievously lacking which did not contain recognition of this. In arranging this important exhibition no effort has been made to give a chronological nor yet an historical survey of Stuart's portraits, rather have we aimed to show a collection of paintings which exemplifies the strength as well as the charm and grace of Stuart's work. This has required that we include portraits he painted in Ireland and England as well as those done in America. His place will always stand among the great portrait painters of the world. 1 GEORGE WASHINGTON Canvas, 25 x 30 inches. Painted, 1795. This portrait of George Washington, showing the right side of the face is known as the Vaughan type, so called for the owner of the first of the type, in contradistinction to the Athenaeum portrait depicting the left side of the face. Park catalogues fifteen of the Vaughan por traits and seventy-four of the Athenaeum portraits. "Philadelphia, 1795. Canvas, 30 x 25 inches. Bust, showing the right side of the face; powdered hair, black coat, white neckcloth and linen shirt ruffle. The background is plain and of a soft crimson and ma roon color. -

Portraits in the Life of Oliver Wolcott^Jn

'Memorials of great & good men who were my friends'': Portraits in the Life of Oliver Wolcott^Jn ELLEN G. MILES LIVER woLCOTT, JR. (1760-1833), like many of his contemporaries, used portraits as familial icons, as ges- Otures in political alliances, and as public tributes and memorials. Wolcott and his father Oliver Wolcott, Sr. (i 726-97), were prominent in Connecticut politics during the last quarter of the eighteenth century and the first quarter of the nineteenth. Both men served as governors of the state. Wolcott, Jr., also served in the federal administrations of George Washington and John Adams. Withdrawing from national politics in 1800, he moved to New York City and was a successful merchant and banker until 1815. He spent the last twelve years of his public life in Con- I am grateful for a grant from the Smithsonian Institution's Research Opportunities Fund, which made it possible to consult manuscripts and see portraits in collecdüns in New York, Philadelphia, Boston, New Haven, î lartford. and Litchfield (Connecticut). Far assistance on these trips I would like to thank Robin Frank of the Yale Universit)' Art Gallery, .'\nne K. Bentley of the Massachusetts Historical Society, and Judith Ellen Johnson and Richard Malley of the Connecticut Historical Society, as well as the society's fonner curator Elizabeth Fox, and Elizabeth M. Komhauscr, chief curator at the Wadsworth Athenaeum, Hartford. David Spencer, a former Smithsonian Institution Libraries staff member, gen- erously assisted me with the VVolcott-Cibbs Family Papers in the Special Collectiims of the University of Oregon Library, Eugene; and tht staffs of the Catalog of American Portraits, National Portrait Ciallery, and the Inventory of American Painting. -

THE DECLARATION of INDEPENDENCE Biographies, Discussion Questions, Suggested Activities and More INDEPENDENCE

THIS DAY IN HISTORY STUDY GUIDE JUL. 4, 1776: THE DECLARATION OF INDEPENDENCE Biographies, discussion questions, suggested activities and more INDEPENDENCE Setting the Stage Even after the initial battles of what would become the Revolutionary War broke out, few colonists desired complete independence from Great Britain, and those who did–like John Adams–were considered radical. Things changed over the course of the next year, however, as Britain attempted to crush the rebels with all the force of its great army. In his message to Parliament in Oc- tober 1775, King George III railed against the rebellious colonies and ordered the enlargement of the royal army and navy. News of this reached America in January 1776, strengthening the radicals’ cause and leading many conserva- tives to abandon their hopes of reconciliation. That same month, the recent British immigrant Thomas Paine published “Common Sense,” in which he ar- gued that independence was a “natural right” and the only possible course for the colonies; the pamphlet sold more than 150,000 copies in its fi rst few weeks in publication. In March 1776, North Carolina’s revolutionary convention became the fi rst to vote in favor of independence; seven other colonies had followed suit by mid-May. On June 7, the Virginia delegate Richard Henry Lee introduced a motion calling for the colonies’ independence before the Continental Con- gress when it met at the Pennsylvania State House (later Independence Hall) in Philadelphia. Amid heated debate, Congress postponed the vote on Lee’s resolution and called a recess for several weeks. Before departing, howev- er, the delegates also appointed a fi ve-man committee–including Thomas Jeff erson of Virginia; John Adams of Massachusetts; Roger Sherman of Con- necticut; Benjamin Franklin of Pennsylvania; and Robert R. -

Resources for Teachers John Trumbull's Declaration Of

Resources for Teachers John Trumbull’s Declaration of Independence CONVERSATION STARTERS • What is happening with the Declaration of Independence in this painting? o The Committee of Five is presenting their draft to the President of the Continental Congress, John Hancock. • Both John Adams and Thomas Jefferson apparently told John Trumbull that, if portraits couldn’t be painted from life or copied from other portraits, it would be better to leave delegates out of the scene than to poorly represent them. Do you agree? o Trumbull captured 37 portraits from life (which means that he met and painted the person). When he started sketching with Jefferson in 1786, 12 signers of the Declaration had already died. By the time he finished in 1818, only 5 signers were still living. • If you were President James Madison, and you wanted four monumental paintings depicting major moments in the American Revolution, which moments would you choose? o Madison and Trumbull chose the surrender of General Burgoyne at Saratoga, the surrender of Lord Cornwallis at Yorktown, the Declaration of Independence, and the resignation of Washington. VISUAL SOURCES John Trumbull, Declaration of Independence (large scale), 1819, United States Capitol https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Declaration_of_Independence_(1819),_by_John_Trumbull.jpg John Trumbull, Declaration of Independence (small scale), 1786-1820, Trumbull Collection, Yale University Art Gallery https://artgallery.yale.edu/collections/objects/69 John Trumbull and Thomas Jefferson, “First Idea of Declaration of Independence, Paris, Sept. 1786,” 1786, Gift of Mr. Ernest A. Bigelow, Yale University Art Gallery https://artgallery.yale.edu/collections/objects/2805 PRIMARY SOURCES Autobiography, Reminiscences and Letters of John Trumbull, from 1756 to 1841 https://archive.org/details/autobiographyre00trumgoog p. -

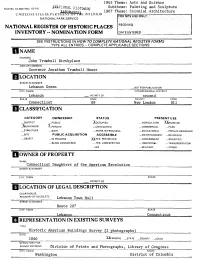

Hclassifi Cation

1965 Theme: Arts and Science Form NO. 10-300 (Re, 10-74) RATIONAL Subtheme : Painting and Sculpture 1967 Theme: Colonial Architecture UNITED STAThS DHPARTl k INTERIOR NATIONAL PARK SERVICE NATIONAL REGISTER OF HISTORIC PLACES INVENTORY -- NOMINATION FORM SEE INSTRUCTIONS IN HOWTO COMPLETE NATIONAL REGISTER FORMS ___________TYPE ALL ENTRIES -- COMPLETE APPLICABLE SECTIONS______ NAME HISTORIC John Trumbull Birthplace AND/OR COMMON Governor Jonathan Trumbull House LOCATION STREETS NUMBER Lebanon Green _NOT FOR PUBLICATION CITY. TOWN CONGRESSIONAL DISTRICT Lebanon —. VICINITY OF second STATE CODE COUNTY CODE Connecticut 09 New London Oil HCLASSIFI CATION CATEGORY OWNERSHIP STATUS PRESENT USE —DISTRICT _PUBLIC -XOCCUPIED —AGRICULTURE XXMUSEIJM JfeuiLDING(S) X_PRIVATE —UNOCCUPIED —COMMERCIAL —PARK —STRUCTURE —BOTH —WORK IN PROGRESS —EDUCATIONAL —PRIVATE RESIDENCE —SITE PUBLIC ACQUISITION ACCESSIBLE —ENTERTAINMENT —RELIGIOUS —OBJECT _IN PROCESS X&YES: RESTRICTED —GOVERNMENT —SCIENTIFIC _ BEING CONSIDERED __YES: UNRESTRICTED —INDUSTRIAL —TRANSPORTATION _NO —MILITARY —OTHER: OWNER OF PROPERTY NAME Connecticut Daughters of the American Revolution "STREET & NUMBER CITY, TOWN STATE VICINITY OF LOCATION OF LEGAL DESCRIPTION COURTHOUSE. REGISTRY OF DEEDS,ETC. Lebanon Town Hall STREET & NUMBER Route 207 CITY. TOWN STATE Lebanon Connecticut I REPRESENTATION IN EXISTING SURVEYS TITLE Historic American Buildings Survey (2 photographs) DATE 1940 XXFEDERAL —STATE —COUNTY —LOCAL DEPOSITORY FOR SURVEY RECORDS Division of Priiits and Photographs, Library of Congress CITY. TOWN STATE Washington District of Columbia DESCRIPTION CONDITION CHECK ONE CHECK ONE —EXCELLENT —DETERIORATED —UNALTERED —ORIGINAL SITE X&OOD —RUINS 3LALTERED X-MOVED DATE 1832—— _FAIR —UNEXPOSED DESCRIBETHE PRESENT AND ORIGINAL (IF KNOWN) PHYSICAL APPEARANCE This wedding present to Jonathan and Faith Trumbull is a two-story, five-bay clapboarded frame house, of simple early Georgian design, with a steep gable roof and a large square central chimney.