Does Freedom of Expression Cause Less Terrorism?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Global Handbook on Hate Speech Laws Get

REBUILDING THE BULWARK OF LIBERTY Tool GLOBAL HANDBOOK ON HATE SPEECH LAWS By Natalie Alkiviadou, Jacob Mchangama and Raghav Mendiratta GLOBAL HANDBOOK ON HATE SPEECH LAWS © Justitia and the authors, 2020 WHO WE ARE Founded in August 2014, Justitia is Denmark’s first judicial think tank. Justitia aims to promote the rule of law and fundamental human rights and freedom rights, both within Denmark and abroad, by educating and influencing policy experts, decision-makers, and the public. In so doing, Justitia offers legal insight and analysis on a range of contemporary issues. The Future of Free Speech is a collaboration between Copenhagen based judicial think tank Justitia, Columbia University’s Global Freedom of Expression and Aarhus University’s Department of Political Science. Free speech is the bulwark of liberty; without it, no free and democratic society has ever been established or thrived. Free expression has been the basis of unprecedented scientific, social and political progress that has benefitted individuals, communities, nations and humanity itself. Millions of people derive protection, knowledge and essential meaning from the right to challenge power, question orthodoxy, expose corruption and address oppression, bigotry and hatred. At the Future of Free Speech, we believe that a robust and resilient culture of free speech must be the foundation for the future of any free, democratic society. We believe that, even as rapid technological change brings new challenges and threats, free speech must continue to serve as an essential ideal and a fundamental right for all people, regardless of race, ethnicity, religion, nationality, sexual orientation, gender or social standing. -

The Proliferation of United Nations Special Procedures Mandates

Expanding or diluting Human Rights? The proliferation of United Nations Special Procedures mandates Article Published Version Freedman, R. and Mchangama, J. (2016) Expanding or diluting Human Rights? The proliferation of United Nations Special Procedures mandates. Human Rights Quarterly, 38 (1). pp. 164-193. ISSN 1085-794X doi: https://doi.org/10.1353/hrq.2016.0012 Available at http://centaur.reading.ac.uk/66578/ It is advisable to refer to the publisher’s version if you intend to cite from the work. See Guidance on citing . Published version at: http://muse.jhu.edu/article/609306 To link to this article DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1353/hrq.2016.0012 Publisher: The John Hopkins University Press All outputs in CentAUR are protected by Intellectual Property Rights law, including copyright law. Copyright and IPR is retained by the creators or other copyright holders. Terms and conditions for use of this material are defined in the End User Agreement . www.reading.ac.uk/centaur CentAUR Central Archive at the University of Reading Reading’s research outputs online ([SDQGLQJRU'LOXWLQJ+XPDQ5LJKWV"7KH3UROLIHUDWLRQRI8QLWHG1DWLRQV 6SHFLDO3URFHGXUHV0DQGDWHV 5RVD)UHHGPDQ-DFRE0FKDQJDPD +XPDQ5LJKWV4XDUWHUO\9ROXPH1XPEHU)HEUXDU\SS $UWLFOH 3XEOLVKHGE\-RKQV+RSNLQV8QLYHUVLW\3UHVV '2,KUT )RUDGGLWLRQDOLQIRUPDWLRQDERXWWKLVDUWLFOH KWWSVPXVHMKXHGXDUWLFOH Access provided by University of Reading (11 Oct 2016 10:18 GMT) HUMAN RIGHTS QUARTERLY Expanding or Diluting Human Rights?: The Proliferation of United Nations Special Procedures Mandates Rosa Freedman* & Jacob Mchangama** ABSTRACT The United Nations Special Procedures system was described by former UN Secretary General Kofi Annan as “the crown jewel” of the UN Human Rights Machinery. Yet, in recent years, the system has expanded rapidly, driven by states creating new mandates frequently on topics not traditionally viewed as human rights. -

Grænser for Europa. Eu Mellem Nationalisme Og Globalisering

R A P P O R T S K E M A (til brug for aflæggelse af rapport for pulje C-bevillinger) Tilskudsmodtag er: FONDEN DE KØBENHAVNSKE FILMFESTIVALER / CPH:DOX Journalnr.: EUFC.2017-0109 Bevilget tilskud: 195.000 kr Projektets titel: GRÆNSER FOR EUROPA? EU MELLEM NATIONALISME OG GLOBALISERING Startdato: 1. marts 2018 Slutdato: 30. marts 2018 Som Danmarks største folkeoplysende kulturbegivenhed lancerede dokumentarfilmfestivalen CPH:DOX i marts 2018 et stort, landsdækkende oplysningsprojekt med fokus på EU’s fremtidige muligheder og udfordringer i krydsfeltet mellem globalisering og nationalisme. Projektet omfattede: - Debatarrangementer med danske og internationale politikere og tænkere - Dokumentarfilmvisninger i kulturhuse, biografer, biblioteker mv. i hele Danmark - Undervisningstiltag for tusinder af skole- og gymnasieelever Projektet forløb overordentligt succesfuldt. Vi havde et mål om afholdelse af minimum 75 arrangementer, men kom op på over 100 arrangementer, som for langt de flestes vedkommende trak fulde huse. Europas udfordringer med globalisering blev belyst gennem en lang række arrangementer, det samme gjaldt nationalisme - ligesom der naturligvis også var en lang række arrangementer, der knyttede direkte an til denne modstilling, fx filmene ‘EuroTrump’ om Geert Wilders, ‘Golden Dawn Girls’ om det græske parti Gyldent Daggry, 'The Other Side of Everything' om nationalisme på Balkan i dag, Our New President om forholdet mellem Europa og Rusland, fake news og truslen fra russiske 'trolde', 'Central Airport THF' om flygtningekrisens udfordring af Europa, den meget aktuelle 'Piazza Vittorio' om den stigende italienske modstand mod immigration, Foreigners Out om Østrigs højrefløj og mange, mange flere. Kort rapport om forløbet: Er aktivitetsmålene for projektet opnået? Anfør mål Aktivitetsmål: Afholdeldelse af 75 og beskriv opfyldelsen. -

Coronation Street Takes on Assisted Dying As Right-To-Die Cases Reach

BHA news BHA news www.humanism.org.uk Issue 1 2014 ‘The only possible basis for a sound morality is mutual tolerance and respect: tolerance of one another’s customs and opinions; respect for one another’s rights and feelings; awareness of one another’s needs.’ — A J Ayer, Humanist Coronation Street takes on assisted dying as right-to-die cases reach Supreme Court Coronation Street has broadcast one of its most memorable episodes, in which the character Hayley Cropper, played by BHA Distinguished Supporter Julie Hesmondhalgh, decides to commit suicide after becoming terminally ill with inoperable cancer. The episode in question was watched by over ten million viewers. Coronation Street’s brave tackling of this important ethical issue takes place as we await the Supreme Court’s judgement on the legal case to establish the right to an assisted death. During the hearings in December, we presented our Kate Rutter, portraying Suzie the humanist evidence in support of Jane Nicklinson, celebrant, at Hayley Cropper's funeral the widow of Tony Nicklinson, who sought and was denied an assisted death, and Humanist Funerals showcased on Paul Lamb, who is seeking the right to an Coronation Street assisted death after being paralysed in a road accident. We have been a party to We were very pleased that ITV producers same time as acknowledging the case throughout as an intervener. of Coronation Street chose to bid and celebrating all that the person The judgement will be announced later farewell to the much loved character of has achieved. this year. Hayley Cropper with a humanist funeral. -

Your Post Has Been Removed

Frederik Stjernfelt & Anne Mette Lauritzen YOUR POST HAS BEEN REMOVED Tech Giants and Freedom of Speech Your Post has been Removed Frederik Stjernfelt Anne Mette Lauritzen Your Post has been Removed Tech Giants and Freedom of Speech Frederik Stjernfelt Anne Mette Lauritzen Humanomics Center, Center for Information and Communication/AAU Bubble Studies Aalborg University University of Copenhagen Copenhagen København S, København SV, København, Denmark København, Denmark ISBN 978-3-030-25967-9 ISBN 978-3-030-25968-6 (eBook) https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-25968-6 © The Editor(s) (if applicable) and The Author(s) 2020. This book is an open access publication. Open Access This book is licensed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/ by/4.0/), which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this book are included in the book’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the book’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permit- ted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. The use of general descriptive names, registered names, trademarks, service marks, etc. in this publication does not imply, even in the absence of a specific statement, that such names are exempt from the relevant protective laws and regulations and therefore free for general use. -

The European Court of Human Rights—A European Constitutional Court? by Jacob Mchangama*

The European Court of Human Rights—A European Constitutional Court? By Jacob Mchangama* egal discussions of constitutionalism will typically focus against the reemergence of totalitarianism.4 As noted in a on national developments and differences between document drafted by high-ranking UK civil servants engaged in various national constitutional systems. However the the drafting of the ECHR: “The original purpose of the Council Lfocus of my remarks will not be on national constitutions and of Europe Convention on Human Rights was to enable public constitutional courts—at least not directly—but rather on the attention to be drawn to any revival of totalitarian methods of idea of supranational or European constitutionalism. This is an government and to provide a forum in which the appropriate idea that holds great appeal to many lawyers and politicians. action could be discussed and decided.”5 The EU and the European Court of Justice (ECJ) is Judicial enforcement was to be the exception; in fact, it obviously central to any discussion of European constitutionalism, was assumed by drafters that the ECHR would not result in but my focus will be on the European Convention on Human any significant problems for the state parties. The UK Attorney- Rights (henceforth ECHR) and in particular on the European General Sir Hartley Shawcross stated: Court of Human Rights (henceforth the Court) set up to No other country engages, or need engage, in any over enforce this convention. nice and meticulous comparison of its own municipal There are those who believe that the ECHR has attained laws against its treaty obligations . -

Vrede Unge Mænd

Vrede unge mænd Tiderne_Vrede unge mænd.indd 1 11/03/11 11.41 Af samme forfatter: Skyld – Historien bag mordet på Antonio Curra, 2007 Tiderne_Vrede unge mænd.indd 2 11/03/11 11.41 Aydin Soei VREDE UNGE MÆND Optøjer og kampen for anerkendelse i et nyt Danmark TIDERNE SKIFTER Tiderne_Vrede unge mænd.indd 3 11/03/11 11.41 Vrede unge mænd – optøjer og kampen for anerkendelse i et nyt Danmark Copyright © 2011 Aydin Soei & Tiderne Skifter Forlagsredaktion: Claus Clausen Sat med minion hos An:Sats, Espergærde og trykt hos Specialtrykkeriet, Viborg ISBN 978-87-7973-477-7 Tiderne Skifter Forlag · Læderstræde 5, 1. sal · 1201 København K Tlf.: 33 18 63 90 · Fax: 33 18 63 91 e-mail: tiderneskifter@tiderneskifter · www.tiderneskifter.dk Tiderne_Vrede unge mænd.indd 4 11/03/11 11.41 Indhold Forord 7 En aften på Blågårds Plads 9 • Fra Iran til Avedøre i 80’ernes Danmark – da ‘minirockerne’ blev erstattet af en ny gruppe drenge 11 Optakt: Optøjer som toppen af isbjerget 23 Februar 2008 – Den første aften med optøjer 25 • Toppen af isbjerget 30 1. Amerikanske tilstande 37 Uroligheder på Nørrebro i 1997 39 • Rodney King-optøjerne som forvarsel til Europa 44 2. 2001 – Skæringspunkt for en ny tid 51 Terrorangreb og politisk systemskifte 53 3. 2003 – Når bopælen bliver en belastning 65 „Men når jeg siger Frederiksberg, så er der ikke alle de fordomme“ 67 • Mistilliden til medierne og bydelsnationalismen 79 4. Kampe om medborgerskabet og medierne 99 Det splittede folk og kulturkampen i 2005 101 • De fraværende stemmer og mistilliden til medierne 108 • Mediestereotyper i katastrofe- situationer 113 5. -

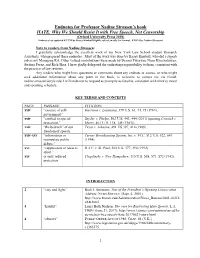

Endnotes for Professor Nadine Strossen's Book HATE: Why We Should Resist It with Free Speech, Not Censorship

Endnotes for Professor Nadine Strossen’s book HATE: Why We Should Resist It with Free Speech, Not Censorship (Oxford University Press 2018) Endnotes last updated 4/27/18 by Kasey Kimball (lightly edited, mostly for format, 4/28/18 by Nadine Strossen) Note to readers from Nadine Strossen: I gratefully acknowledge the excellent work of my New York Law School student Research Assistants, who prepared these endnotes. Most of the work was done by Kasey Kimball, who did a superb job as my Managing RA. Other valued contributions were made by Dennis Futoryan, Nana Khachaturyan, Stefano Perez, and Rick Shea. I have gladly delegated the endnoting responsibility to them, consistent with the practice of law reviews. Any readers who might have questions or comments about any endnote or source, or who might seek additional information about any point in the book, is welcome to contact me via Email: [email protected]. I will endeavor to respond as promptly as feasible, consistent with a heavy travel and speaking schedule. KEY TERMS AND CONCEPTS PAGE PASSAGE CITATION xxiv “essence of self- Garrison v. Louisiana, 379 U.S. 64, 74, 75 (1964). government.” xxiv “entitled to special Snyder v. Phelps, 562 U.S. 443, 444 (2011) (quoting Connick v. protection.” Myers, 461 U. S. 138, 145 (1983)). xxiv “the bedrock” of our Texas v. Johnson, 491 US 397, 414 (1989). freedom of speech. xxiv-xxv “information or Turner Broadcasting System, Inc. v. FCC, 512 U.S. 622, 641 manipulate public (1994). debate.” xxv “suppression of ideas is R.A.V. v. St. -

Classical Liberalism and Modern Political Economy in Denmark

Classical liberalism and modern political economy in Denmark Kurrild-Klitgaard, Peter Published in: Econ Journal Watch Publication date: 2015 Document version Publisher's PDF, also known as Version of record Citation for published version (APA): Kurrild-Klitgaard, P. (2015). Classical liberalism and modern political economy in Denmark. Econ Journal Watch, 12(3), 400-431. https://econjwatch.org/articles/classical-liberalism-and-modern-political-economy-in-denmark Download date: 01. okt.. 2021 Discuss this article at Journaltalk: http://journaltalk.net/articles/5895 ECON JOURNAL WATCH 12(3) September 2015: 400–431 Classical Liberalism and Modern Political Economy in Denmark Peter Kurrild-Klitgaard1 LINK TO ABSTRACT Over the last century, classical liberalism has not had a strong presence in Danish social science, including economics. Several studies have shown that social scientists in Denmark tilt leftwards. In a 1995–96 survey only 7 percent of political scientists and 3 percent of sociologists said they had voted for (classical-)liberal or conservative parties, whereas support for socialist parties among the same groups were 51 percent and 78 percent. Lawyers and economists were more evenly split between left and right, but even there the left dominated: 31 percent and 25 percent for at least nominally free-market friendly parties and 38 percent and 36 percent for socialist parties.2 Very vocal free-market voices in academia have been rare. This marginalization of liberalism was not always the case. Denmark was among the first countries to see publication of a translation of Adam Smith’s Wealth of Nations (Smith 1779/1776; see Rae 1895, ch. 24; Kurrild-Klitgaard 1998; 2004). -

Denmark,Liberalism

Discuss this article at Journaltalk: http://journaltalk.net/articles/5895 ECON JOURNAL WATCH 12(3) September 2015: 400–431 Classical Liberalism and Modern Political Economy in Denmark Peter Kurrild-Klitgaard1 LINK TO ABSTRACT Over the last century, classical liberalism has not had a strong presence in Danish social science, including economics. Several studies have shown that social scientists in Denmark tilt leftwards. In a 1995–96 survey only 7 percent of political scientists and 3 percent of sociologists said they had voted for (classical-)liberal or conservative parties, whereas support for socialist parties among the same groups were 51 percent and 78 percent. Lawyers and economists were more evenly split between left and right, but even there the left dominated: 31 percent and 25 percent for at least nominally free-market friendly parties and 38 percent and 36 percent for socialist parties.2 Very vocal free-market voices in academia have been rare. This marginalization of liberalism was not always the case. Denmark was among the first countries to see publication of a translation of Adam Smith’s Wealth of Nations (Smith 1779/1776; see Rae 1895, ch. 24; Kurrild-Klitgaard 1998; 2004). Throughout the 19th century the emerging field of economics at the University of Copenhagen was visibly inspired not only by Smith and David Ricardo but also the “Manchester liberals” and French classical liberal economists Jean Baptiste Say and Frédéric Bastiat, of whose works timely translations were made. The university had professors of economics who today would be termed classical liberals, e.g., Oluf Christian Olufsen (1764–1827), Christian G. -

22 December 2020 Hate Crime Laws

22 December 2020 Hate Crime Laws Response to Public Consultation (Law Commission) Authors: Jacob Mchangama (Director), Natalie Alkiviadou (Senior Research Fellow), Justitia, Denmark Justitia: Founded in August 2014, Justitia is Denmark’s first judicial think tank. Justitia aims to promote the rule of law and fundamental human rights and freedom rights both within Denmark and abroad by educating and influencing policy experts, decision-makers, and the public. Justitia´s Future of Free Speech Project focuses specifically on freedom of expression at the global level. Brief summary of our views: Justitia is concerned about the freedom of expression implications of the manner in which ‘stirring up offences’ are conceptualised, the “scope creep” in terms of protected characteristics and the “censorship envy” that may be created as a result of the inclusion of some protected characteristics and not others. Issue 1: Incorporating ‘stirring up hatred’ in the consultation on hate crimes The consultation document notes that hate crime can encompass verbal abuse and hate speech. It proceeds, in paragraph 1.25 to note that ‘every hate crime involves an action as well as a mental state. The law does not punish a neo-Nazi for his or her beliefs, but if those beliefs lead him or her to attack someone Jewish or desecrate a mosque, then the law rightly steps in.’ However, the consultation document does not only deal with attacks as hate crimes but also incorporates hate speech into its conceptual framework, with the two above positions set out in the consultation document being in antithesis with each other. Scholars have discussed the impact of hate crimes in comparison with other crimes, and particularly whether or not such crimes are more destructive than others and thus merit the element of aggravation. -

Hate Speech Laws and Blasphemy Laws: Parallels Show Problems with the U.N

Emory International Law Review Volume 35 Issue 2 2021 Hate Speech Laws and Blasphemy Laws: Parallels Show Problems with the U.N. Strategy and Plan of Action on Hate Speech Meghan Fischer Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarlycommons.law.emory.edu/eilr Part of the International Law Commons Recommended Citation Meghan Fischer, Hate Speech Laws and Blasphemy Laws: Parallels Show Problems with the U.N. Strategy and Plan of Action on Hate Speech, 35 Emory Int'l L. Rev. 177 (2021). Available at: https://scholarlycommons.law.emory.edu/eilr/vol35/iss2/1 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at Emory Law Scholarly Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Emory International Law Review by an authorized editor of Emory Law Scholarly Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. FISCHER_3.22.21 3/23/2021 4:02 PM HATE SPEECH LAWS AND BLASPHEMY LAWS: PARALLELS SHOW PROBLEMS WITH THE U.N. STRATEGY AND PLAN OF ACTION ON HATE SPEECH Meghan Fischer* ABSTRACT In May 2019, the United Nations Secretary-General introduced the U.N. Strategy and Plan of Action on Hate Speech, an influential campaign that poses serious risks to religious and political minorities because its definition of hate speech parallels elements common to blasphemy laws. U.N. human rights entities have denounced blasphemy laws because they are vague, broad, and prone to arbitrary enforcement, enabling the authorities to use them to attack religious minorities, political opponents, and people who have minority viewpoints. Likewise, the Strategy and Plan of Action’s definition of hate speech is ambiguous and relies entirely on subjective interpretation, opening the door to arbitrary and malicious accusations and prosecutions.