Asia Overview

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Annual Report

COUNCIL ON FOREIGN RELATIONS ANNUAL REPORT July 1,1996-June 30,1997 Main Office Washington Office The Harold Pratt House 1779 Massachusetts Avenue, N.W. 58 East 68th Street, New York, NY 10021 Washington, DC 20036 Tel. (212) 434-9400; Fax (212) 861-1789 Tel. (202) 518-3400; Fax (202) 986-2984 Website www. foreignrela tions. org e-mail publicaffairs@email. cfr. org OFFICERS AND DIRECTORS, 1997-98 Officers Directors Charlayne Hunter-Gault Peter G. Peterson Term Expiring 1998 Frank Savage* Chairman of the Board Peggy Dulany Laura D'Andrea Tyson Maurice R. Greenberg Robert F Erburu Leslie H. Gelb Vice Chairman Karen Elliott House ex officio Leslie H. Gelb Joshua Lederberg President Vincent A. Mai Honorary Officers Michael P Peters Garrick Utley and Directors Emeriti Senior Vice President Term Expiring 1999 Douglas Dillon and Chief Operating Officer Carla A. Hills Caryl R Haskins Alton Frye Robert D. Hormats Grayson Kirk Senior Vice President William J. McDonough Charles McC. Mathias, Jr. Paula J. Dobriansky Theodore C. Sorensen James A. Perkins Vice President, Washington Program George Soros David Rockefeller Gary C. Hufbauer Paul A. Volcker Honorary Chairman Vice President, Director of Studies Robert A. Scalapino Term Expiring 2000 David Kellogg Cyrus R. Vance Jessica R Einhorn Vice President, Communications Glenn E. Watts and Corporate Affairs Louis V Gerstner, Jr. Abraham F. Lowenthal Hanna Holborn Gray Vice President and Maurice R. Greenberg Deputy National Director George J. Mitchell Janice L. Murray Warren B. Rudman Vice President and Treasurer Term Expiring 2001 Karen M. Sughrue Lee Cullum Vice President, Programs Mario L. Baeza and Media Projects Thomas R. -

Comedy Therapy

VFW’S HURRICANE DISASTER RELIEF TET 50 YEARS LATER OFFENSIVE An artist emerges from the trenches of WWI COMEDYAS THERAPY Leading the way in supporting those who lead the way. USAA is proud to join forces with the Veterans of Foreign Wars in helping support veterans and their families. USAA means United Services Automobile Association and its affiliates. The VFW receives financial support for this sponsorship. © 2017 USAA. 237701-0317 VFW’S HURRICANE DISASTER RELIEF TET 50 YEARS LATER OFFENSIVE An artist emerges from the trenches of WWI COMEDYAS THERAPY JANUARY 2018 Vol. 105 No. 4 COVER PHOTO: An M-60 machine gunner with 2nd Bn., 5th Marines, readies himself for another assault during the COMEDY HEALS Battle of Hue during the Tet Offensive in 20 A VFW member in New York started a nonprofit that offers veterans February 1968. Strapped to his helmet is a a creative artistic outlet. One component is a stand-up comedy work- wrench for his gun, a first-aid kit and what appears to be a vial of gun oil. If any VFW shop hosted by a Post on Long Island. BY KARI WILLIAMS magazine readers know the identity of this Marine, please contact us with details at [email protected]. Photo by Don ‘A LOT OF DEVASTATION’ McCullin/Contact Press Images. After hurricanes Harvey, Irma and Maria 26 ON THE COVER roared through Texas, Florida and Puer- 14 to Rico last fall, VFW Posts from around Tet Offensive the nation rallied to aid those affected. 20 Comedy Heals Meanwhile, VFW National Headquar- 26 Hurricane Disaster Relief ters had raised nearly $250,000 in finan- 32 An Artist Emerges cial support through the end of October. -

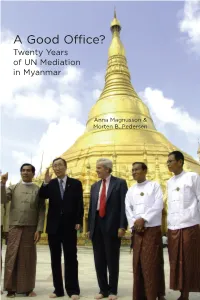

A Good Office? Twenty Years of UN Mediation in Myanmar

A Good Office? Twenty Years of UN Mediation in Myanmar Anna Magnusson & Morten B. Pedersen A Good Office? Twenty Years of UN Mediation in Myanmar Anna Magnusson and Morten B. Pedersen International Peace Institute, 777 United Nations Plaza, New York, NY 10017 www.ipinst.org © 2012 by International Peace Institute All rights reserved. Published 2012. Cover Photo: UN Secretary-General Ban Ki-moon, 2nd left, and UN Undersecretary-General for Humanitarian Affairs John Holmes, center, pose for a group photograph with Myanmar Foreign Minister Nyan Win, left, and two other unidentified Myanmar officials at Shwedagon Pagoda in Yangon, Myanmar, May 22, 2008 (AP Photo). Disclaimer: The views expressed in this publication represent those of the authors and not necessarily those of IPI. IPI welcomes consideration of a wide range of perspectives in the pursuit of a well-informed debate on critical policies and issues in international affairs. The International Peace Institute (IPI) is an independent, interna - tional institution dedicated to promoting the prevention and settle - ment of conflicts between and within states through policy research and development. IPI owes a debt of thanks to its many generous donors, including the governments of Norway and Finland, whose contributions make publications like this one possible. In particular, IPI would like to thank the government of Sweden and the Swedish International Development Cooperation Agency (SIDA) for their support of this project. ISBN: 0-937722-87-1 ISBN-13: 978-0-937722-87-9 CONTENTS Acknowledgements . v Acronyms . vii Introduction . 1 1. The Beginning of a Very Long Engagement (1990 –1994) Strengthening the Hand of the Opposition . -

Prologue This Report Is Submitted Pursuant to the ―United Nations Participation Act of 1945‖ (Public Law 79-264)

Prologue This report is submitted pursuant to the ―United Nations Participation Act of 1945‖ (Public Law 79-264). Section 4 of this law provides, in part, that: ―The President shall from time to time as occasion may require, but not less than once each year, make reports to the Congress of the activities of the United Nations and of the participation of the United States therein.‖ In July 2003, the President delegated to the Secretary of State the authority to transmit this report to Congress. The United States Participation in the United Nations report is a survey of the activities of the U.S. Government in the United Nations and its agencies, as well as the activities of the United Nations and those agencies themselves. More specifically, this report seeks to assess UN achievements during 2007, the effectiveness of U.S. participation in the United Nations, and whether U.S. goals were advanced or thwarted. The United States is committed to the founding ideals of the United Nations. Addressing the UN General Assembly in 2007, President Bush said: ―With the commitment and courage of this chamber, we can build a world where people are free to speak, assemble, and worship as they wish; a world where children in every nation grow up healthy, get a decent education, and look to the future with hope; a world where opportunity crosses every border. America will lead toward this vision where all are created equal, and free to pursue their dreams. This is the founding conviction of my country. It is the promise that established this body. -

Structure and Law Enforcement of Environmental Police in China

Cambridge Journal of China Studies 33 Structure and Law Enforcement of Environmental Police in China Michael WUNDERLICH Free University of Berlin, Germany Abstract: Is the Environmental Police (EP) the solution to close the remaining gaps preventing an effective Environmental Protection Law (EPL) implementation? By analyzing the different concepts behind and needs for a Chinese EP, this question is answered. The Environmental Protection Bureau (EPB) has the task of establishing, implementing, and enforcing the environmental law. But due to the fragmented structure of environmental governance in China, the limited power of the EPBs local branches, e.g. when other laws overlap with the EPL, low level of public participation, and lacking capacity and personnel of the EPBs, they are vulnerable and have no effective means for law enforcement. An EP could improve this by being a legal police force. Different approaches have been implemented on a local basis, e.g. the Beijing or Jiangsu EP, but they still lack a legal basis and power. Although the 2014 EPL tackled many issues, some implementation problems remain: The Chinese EP needs a superior legal status as well as the implementation of an EP is not further described. It is likely that the already complex police structure further impedes inter-department-cooperation. Thus, it was proposed to unite all environment-related police in the EP. Meanwhile the question will be raised, which circumstance is making large scale environmental pollution possible and which role environmental ethics play when discussing the concept of EPs. Key Words: China, Environmental Police, Law Enforcement, Environmental Protection Law The author would like to show his gratitude to Ms. -

Democratic Centralism and Administration in China

This is the accepted version of the chapter published in: F Hualing, J Gillespie, P Nicholson and W Partlett (eds), Socialist Law in Socialist East Asia, Cambridge University Press (2018) Democratic Centralism and Administration in China Sarah BiddulphP0F 1 1. INTRODUCTION The decision issued by the fourth plenary session of the 18th Central Committee of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP, or Party) in 2014 on Some Major Questions in Comprehensively Promoting Governing the Country According to Law (the ‘Fourth Plenum Decision’) reiterated the Party’s determination to build a ‘socialist rule of law system with Chinese characteristics’.P1F 2P What does this proclamation of the ‘socialist’ nature of China’s version of rule of law mean, if anything? Development of a notion of socialist rule of law in China has included many apparently competing and often mutually inconsistent narratives and trends. So, in searching for indicia of socialism in China’s legal system it is necessary at the outset to acknowledge that what we identify as socialist may be overlaid with other important influences, including at least China’s long history of centralised, bureaucratic governance, Maoist forms of ‘adaptive’ governanceP2F 3P and Western ideological, legal and institutional imports, outside of Marxism–Leninism. In fact, what the Chinese party-state labels ‘socialist’ has already departed from the original ideals of European socialists. This chapter does not engage in a critique of whether Chinese versions of socialism are really ‘socialist’. Instead it examines the influence on China’s legal system of democratic centralism, often attributed to Lenin, but more significantly for this book project firmly embraced by the party-state as a core element of ‘Chinese socialism’. -

Crime Feeds on Legal Activities: Daily Mobility Flows Help to Explain Thieves' Target Location Choices

Journal of Quantitative Criminology https://doi.org/10.1007/s10940-019-09406-z ORIGINAL PAPER Crime Feeds on Legal Activities: Daily Mobility Flows Help to Explain Thieves’ Target Location Choices Guangwen Song1 · Wim Bernasco2,3 · Lin Liu1,4 · Luzi Xiao1 · Suhong Zhou5 · Weiwei Liao5 © The Author(s) 2019 Abstract Objective According to routine activity theory and crime pattern theory, crime feeds on the legal routine activities of ofenders and unguarded victims. Based on this assumption, the present study investigates whether daily mobility fows of the urban population help predict where individual thieves commit crimes. Methods Geocoded tracks of mobile phones are used to estimate the intensity of popula- tion mobility between pairs of 1616 communities in a large city in China. Using data on 3436 police-recorded thefts from the person, we apply discrete choice models to assess whether mobility fows help explain where ofenders go to perpetrate crime. Results Accounting for the presence of crime generators and distance to the ofender’s home location, we fnd that the stronger a community is connected by population fows to where the ofender lives, the larger its probability of being targeted. Conclusions The mobility fow measure is a useful addition to the estimated efects of dis- tance and crime generators. It predicts the locations of thefts much better than the presence of crime generators does. However, it does not replace the role of distance, suggesting that ofenders are more spatially restricted than others, or that even within their activity spaces they prefer to ofend near their homes. Keywords Crime location choice · Theft from the person · Mobility · Routine activities · China * Lin Liu [email protected] 1 Center of Geo-Informatics for Public Security, School of Geographical Sciences, Guangzhou University, Guangzhou, China 2 Netherlands Institute for the Study of Crime and Law Enforcement (NSCR), P.O. -

China's Environmental Super Ministry Reform

Copyright © 2009 Environmental Law Institute®, Washington, DC. reprinted with permission from ELR®, http://www.eli.org, 1-800-433-5120. n March 15, 2008, China’s Eleventh National Peo- China’s ple’s Congress passed the super ministry reform (SMR) motion proposed by the State Council and Ocreated five “super ministries,” mostly combinations of two or Environmental more previous ministries or departments. The main purpose of this SMR was to avoid overlapping governmental responsi- Super Ministry bilities by combining departments with similar authority and closely related functions. One of the highlights was the eleva- tion of the State Environmental Protection Administration Reform: (SEPA) to the Ministry of Environmental Protection (MEP), which we also refer to as the environmental SMR. Background, The reference to super ministry is shorthand for the creation of a “comprehensive responsibilities super administrative min- istry framework.”1 In order to promote comprehensive man- Challenges, and agement and coordination, several departments are merged into a new entity, the super ministry, based on their similar the Future goals and responsibilities. By enlarging the ministry’s respon- sibilities and authority, the reform essentially turns some inter- departmental tasks to intradepartmental issues, so one single department can cope with comprehensive problems from by Xin QIU and Honglin LI multiple perspectives, avoiding overlapping responsibilities and authority. Thus, administrative efficiency is increased and Xin QIU is a Ph.D. candidate and visiting fellow administrative costs are reduced. at Vermont Law School. Honglin LI is Director During this SMR, MEP was upgraded and was the only of Law Programs, Yale-China Association.* department to retain its organizational structure and govern- mental responsibilities.2 This demonstrates the strong political will and commitment of China’s central government to envi- Editors’ Summary ronmental protection. -

List of Presidents of the Presidents United Nations General Assembly

Sixty-seventh session of the General Assembly To convene on United Nations 18 September 2012 List of Presidents of the Presidents United Nations General Assembly Session Year Name Country Sixty-seventh 2012 Mr. Vuk Jeremić (President-elect) Serbia Sixty-sixth 2011 Mr. Nassir Abdulaziz Al-Nasser Qatar Sixty-fifth 2010 Mr. Joseph Deiss Switzerland Sixty-fourth 2009 Dr. Ali Abdussalam Treki Libyan Arab Jamahiriya Tenth emergency special (resumed) 2009 Father Miguel d’Escoto Brockmann Nicaragua Sixty-third 2008 Father Miguel d’Escoto Brockmann Nicaragua Sixty-second 2007 Dr. Srgjan Kerim The former Yugoslav Republic of Macedonia Tenth emergency special (resumed twice) 2006 Sheikha Haya Rashed Al Khalifa Bahrain Sixty-first 2006 Sheikha Haya Rashed Al Khalifa Bahrain Sixtieth 2005 Mr. Jan Eliasson Sweden Twenty-eighth special 2005 Mr. Jean Ping Gabon Fifty-ninth 2004 Mr. Jean Ping Gabon Tenth emergency special (resumed) 2004 Mr. Julian Robert Hunte Saint Lucia (resumed twice) 2003 Mr. Julian Robert Hunte Saint Lucia Fifty-eighth 2003 Mr. Julian Robert Hunte Saint Lucia Fifty-seventh 2002 Mr. Jan Kavan Czech Republic Twenty-seventh special 2002 Mr. Han Seung-soo Republic of Korea Tenth emergency special (resumed twice) 2002 Mr. Han Seung-soo Republic of Korea (resumed) 2001 Mr. Han Seung-soo Republic of Korea Fifty-sixth 2001 Mr. Han Seung-soo Republic of Korea Twenty-sixth special 2001 Mr. Harri Holkeri Finland Twenty-fifth special 2001 Mr. Harri Holkeri Finland Tenth emergency special (resumed) 2000 Mr. Harri Holkeri Finland Fifty-fifth 2000 Mr. Harri Holkeri Finland Twenty-fourth special 2000 Mr. Theo-Ben Gurirab Namibia Twenty-third special 2000 Mr. -

The United Nations at 70 Isbn: 978-92-1-101322-1

DOUBLESPECIAL DOUBLESPECIAL asdf The magazine of the United Nations BLE ISSUE UN Chronicle ISSUEIS 7PMVNF-**t/VNCFSTt Rio+20 THE UNITED NATIONS AT 70 ISBN: 978-92-1-101322-1 COVER.indd 2-3 8/19/15 11:07 AM UNDER-SECRETARY-GENERAL FOR COMMUNICATIONS AND PUBLIC INFORMATION Cristina Gallach DIRECTOR OF PUBLICATION Maher Nasser EDITOR-IN-CHIEF Ramu Damodaran EDITOR Federigo Magherini ART AND DESIGN Lavinia Choerab EDITORIAL ASSISTANTS Lyubov Ginzburg, Jennifer Payulert, Jason Pierce SOCIAL MEDIA ASSISTANT Maria Laura Placencia The UN Chronicle is published quarterly by the Outreach Division of the United Nations Department of Public Information. Please address all editorial correspondence: By e-mail [email protected] By phone 1 212 963-6333 By fax 1 917 367-6075 By mail UN Chronicle, United Nations, Room S-920 New York, NY 10017, USA Subscriptions: Customer service in the USA: United Nations Publications Turpin Distribution Service PO Box 486 New Milford, CT 06776-0486 USA Email: [email protected] Web: ebiz.turpin-distribution.com Tel +1-860-350-0041 Fax +1-860-350-0039 Customer service in the UK: United Nations Publications Turpin Distribution Service Pegasus Drive, Stratton Business Park Biggleswade SG18 8TQ United Kingdom Email: [email protected] Web: ebiz.turpin-distribution.com Tel +1 44 (0) 1767 604951 Fax +1 44 (0) 1767 601640 Reproduction: Articles contained in this issue may be reproduced for educational purposes in line with fair use. Please send a copy of the reprint to the editorial correspondence address shown above. However, no part may be reproduced for commercial purposes without the expressed written consent of the Secretary, Publications Board, United Nations, Room S-949 New York, NY 10017, USA © 2015 United Nations. -

It's Not What Is on Paper, but What Is in Practice: China's New Labor Contract Law and the Enforcement Problem

Washington University Global Studies Law Review Volume 8 Issue 3 January 2009 It's Not What Is on Paper, but What Is in Practice: China's New Labor Contract Law and the Enforcement Problem Yin Lily Zheng Washington University School of Law Follow this and additional works at: https://openscholarship.wustl.edu/law_globalstudies Part of the Comparative and Foreign Law Commons, and the Labor and Employment Law Commons Recommended Citation Yin Lily Zheng, It's Not What Is on Paper, but What Is in Practice: China's New Labor Contract Law and the Enforcement Problem, 8 WASH. U. GLOBAL STUD. L. REV. 595 (2009), https://openscholarship.wustl.edu/law_globalstudies/vol8/iss3/7 This Note is brought to you for free and open access by the Law School at Washington University Open Scholarship. It has been accepted for inclusion in Washington University Global Studies Law Review by an authorized administrator of Washington University Open Scholarship. For more information, please contact [email protected]. IT’S NOT WHAT IS ON PAPER, BUT WHAT IS IN PRACTICE: CHINA’S NEW LABOR CONTRACT LAW AND THE ENFORCEMENT PROBLEM INTRODUCTION After decades of implementing a lifetime employment system, China has decided to shift gear and rely on private contracts to regulate domestic labor relations.1 The new Labor Contract Law, which officially took effect on January 1, 2008, memorializes this change.2 Proponents of the new law lauded it as “the most concerted effort to protect workers’ rights.”3 Yet many provisions in the law touched the nerves of quite a few domestic and foreign businesses in China4 and are criticized as overly generous to labor 5 rights. -

High-Level Seminar on Peacebuilding, National Reconciliation and Democratization in Asia (Venue: UN University) General Chairman: Mr

High-Level Seminar on Peacebuilding, National Reconciliation and Democratization in Asia (Venue: UN University) General Chairman: Mr. Yasushi Akashi Introductory remarks: Mr. Yasushi Akashi, Representative of the Government of Japan on Peace-Building, Rehabilitation 9:00- Opening and Reconstruction of Sri Lanka Session 9:05- Keynote Speech: H.E. Mr. Fumio Kishida, Minister for Foreign Affairs, Japan H.E. Dr. José Ramos-Horta, Former President , The Democratic Republic of Timor-Leste (Chair of the High-Level Independent Panel on UN Peace Operations) 9:20 - 10:20 Mr. Mangala Samaraweera, Minister of Foreign Affairs , the Government of Sri Lanka Speech session H.E. Al Haj Murad Ebrahim, Chairman of Moro Islamic Liberation Front (MILF) Mr. Yohei Sasakawa, Special Envoy of the Government of Japan for National Reconciliation in Myanmar Morning Chair: Dr. David Malone, Rector of the United Nations University Session H.E. Dr. Surin Pitsuwan, Former Secretary-General of ASEAN 10:30 - 12:00 Dr. Akihiko Tanaka, President of the Japan International Cooperation Agency (JICA) Interactive session Ms. Noeleen Heyzer, Special Advisor of the UN Secretary-General for Timor-Leste Dr. Takashi Shiraishi, President of the National Graduate Institute for Policy Studies Prof. Akiko Yamanaka, Special Ambassador for Peacebuilding, Japan Panel Discussion 1 Panel Discussion 2 Panel Discussion 3 Consolidation of Peace and Socio- Harmonization in Diversity and Peacebuilding and Women and Children Economic Development (Politico- Moderation (Socio-Cultural Aspect) Economic Aspect) 【Moderator】 【Moderator】 【Moderator】 Dr. Toshiya Hoshino, Professor, Vice Mr. Sebastian von Einsiedel, Director, Prof. Akiko Yuge, Professor, Hosei President, Osaka University the Centre for Policy Research, United University (Former Director, Bureau of Nations University Management, UNDP) 【Panelists】 【Panelists】 【Panelists】 <Cambodia> <Malaysia> <Philippines> H.E.