Lipid-Lowering Drugs and Risk of New- Onset Diabetes: a Cohort Study Using Japanese Healthcare Data Linked to Clinical Data for Health Screening

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Lipid Lowering Agents, Cognitive Decline, and Dementia: the Three-City Study

Lipid lowering agents, cognitive decline, and dementia: the three-city study. Marie-Laure Ancelin, Isabelle Carrière, Pascale Barberger-Gateau, Sophie Auriacombe, Olivier Rouaud, Spiros Fourlanos, Claudine Berr, Anne-Marie Dupuy, Karen Ritchie To cite this version: Marie-Laure Ancelin, Isabelle Carrière, Pascale Barberger-Gateau, Sophie Auriacombe, Olivier Rouaud, et al.. Lipid lowering agents, cognitive decline, and dementia: the three-city study.: Lipid Lowering Agents and Cognitive Decline. Journal of Alzheimer’s Disease, IOS Press, 2012, 30 (3), pp.629-37. 10.3233/JAD-2012-120064. inserm-00707350 HAL Id: inserm-00707350 https://www.hal.inserm.fr/inserm-00707350 Submitted on 12 Jun 2012 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Lipid lowering agents, cognitive decline, and dementia: the three-city study Marie-Laure Ancelin 1 * , Isabelle Carrière 1 , Pascale Barberger-Gateau 2 , Sophie Auriacombe 2 , Olivier Rouaud 3 , Spiros Fourlanos 4 , Claudine Berr 1 , Anne-Marie Dupuy 1 5 , Karen Ritchie 1 6 1 Neuropsychiatrie : Recherche Epidémiologique -

Stems for Nonproprietary Drug Names

USAN STEM LIST STEM DEFINITION EXAMPLES -abine (see -arabine, -citabine) -ac anti-inflammatory agents (acetic acid derivatives) bromfenac dexpemedolac -acetam (see -racetam) -adol or analgesics (mixed opiate receptor agonists/ tazadolene -adol- antagonists) spiradolene levonantradol -adox antibacterials (quinoline dioxide derivatives) carbadox -afenone antiarrhythmics (propafenone derivatives) alprafenone diprafenonex -afil PDE5 inhibitors tadalafil -aj- antiarrhythmics (ajmaline derivatives) lorajmine -aldrate antacid aluminum salts magaldrate -algron alpha1 - and alpha2 - adrenoreceptor agonists dabuzalgron -alol combined alpha and beta blockers labetalol medroxalol -amidis antimyloidotics tafamidis -amivir (see -vir) -ampa ionotropic non-NMDA glutamate receptors (AMPA and/or KA receptors) subgroup: -ampanel antagonists becampanel -ampator modulators forampator -anib angiogenesis inhibitors pegaptanib cediranib 1 subgroup: -siranib siRNA bevasiranib -andr- androgens nandrolone -anserin serotonin 5-HT2 receptor antagonists altanserin tropanserin adatanserin -antel anthelmintics (undefined group) carbantel subgroup: -quantel 2-deoxoparaherquamide A derivatives derquantel -antrone antineoplastics; anthraquinone derivatives pixantrone -apsel P-selectin antagonists torapsel -arabine antineoplastics (arabinofuranosyl derivatives) fazarabine fludarabine aril-, -aril, -aril- antiviral (arildone derivatives) pleconaril arildone fosarilate -arit antirheumatics (lobenzarit type) lobenzarit clobuzarit -arol anticoagulants (dicumarol type) dicumarol -

The Effects of Statin and Fibrate Drugs on Cholesterol Metabolism And

The effects of statin and fibrate drugs on cholesterol metabolism and steroid production in two fish species. By Aziz Al-Habsi Thesis submitted to the Faculty of Graduate and Postdoctoral Studies University of Ottawa In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the PhD degree in the Ottawa-Carleton Institute of Biology Thèse soumise à la Faculté des Études Supérieurs et Postdoctorales Université d’Ottawa En vue de la réalisation partielle du doctorat à L’Institut de Biologie Ottawa-Carleton ©Aziz Al-Habsi, Ottawa, Canada, 2014 This thesis is dedicated to my wife and children who have always stood by me and dealt with all my absence from many family occasions with a smile. ii Acknowledgments Completing a PhD is truly a marathon event, and I would not have able to complete this journey without the aid and support of countless people over the past seven years. First and foremost I would like to gratefully and sincerely thank my supervisor Dr. Thomas W. Moon for his guidance, understanding, friendship, and most importantly, his patience during my graduate studies at University of Ottawa. His mentorship was paramount in providing a well-rounded experience consistent my long-term career goals. He encouraged me not only to be a biologist but also be an instructor and independent thinker. I am not sure many graduate students are given the opportunity to develop their own individuality and self- sufficiency by being allowed to work with such independence. For everything you’ve done for me, Dr. Moon, I thank you. I would like to extend my thanks the Department of Biology at University of Ottawa, especially those members of my doctoral committee for their input, valuable discussions and accessibility. -

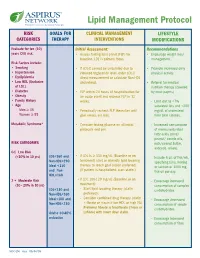

Lipid Management Protocol

Lipid Management Protocol RISK GOALS FOR CLINICAL MANAGEMENT LIFESTYLE CATEGORIES THERAPY INTERVENTIONS MODIFICATIONS Evaluate for ten (10) Initial Assessment: Recommendations years CVD risk. • Assess fasting lipid panel (FLP) for • Encourage weight loss/ baseline. LDL is primary focus. management. Risk Factors include: • Smoking • If LDL-C cannot be calculated due to • Promote increased daily • Hypertension elevated triglyceride level, order LDL-C physical activity. • Dyslipidemia direct measurement or calculate Non-HDL • Low HDL (Exclusive cholesterol. • Referral for medical of LDL) nutrition therapy (covered • Diabetes • FLP within 24 hours of hospitalization for by most payers) • Obesity an acute event and recheck FLP in 12 • Family History weeks. - Limit diet to <7% • Age saturated fats and <200 Men ≥ 45 • Periodically recheck FLP thereafter until mg/dL of cholesterol Women ≥ 55 goal values are met. from total calories. Metabolic Syndrome* • Consider fasting glucose on all initial - Increased consumption protocols and prn. of monounsaturated fatty acids (olive/ peanut/ canola oils, RISK CATEGORIES nuts/peanut butter, avocado, olives). 0-1 Low Risk (<10% in 10 yrs) LDL<160 and • If LDL is ≥ 130 mg/dL (Baseline or on - Include 6 oz. of fish/wk, Non-HDL<190 treatment) start or intensify lipid lowering specifying tuna, herring Ideal <130 therapy to reach goal (statin preferred). or salmon or 1000 mg and Non- (If patient is hospitalized, start statin.) fish oil per day. HDL<160 2 + Moderate Risk • If LDL 100-129 mg/dL (Baseline or on - Encourage increased (10 - 20% in 10 yrs) treatment): consumption of complex LDL<130 and - Start lipid lowering therapy (statin carbohydrates. Non-HDL<160 preferred). -

1 Lipid Lowering Agents, Cognitive Decline, and Dementia

Lipid Lowering Agents, Cognitive Decline, and Dementia: The Three-City Study Marie-Laure Ancelin, PhD.a,b,§,*, Isabelle Carrière, PhD.a,b,§, Pascale Barberger-Gateau PhD.c, Sophie Auriacombe, MDc, Olivier Rouaud, MDd, Spiros Fourlanos, MD, PhD.e, Claudine Berr, PhD.a,b, Anne-Marie Dupuy, PhD.a,b,f, Karen Ritchie, PhD.a,b,g Running title: Lipid Lowering Agents and Cognitive Decline a Inserm, U1061, Montpellier, F-34093 France b Université Montpellier 1, Montpellier, France c Inserm, U897, Bordeaux, F-33076 France d Centre Mémoire Ressources et Recherche, Centre Hospitalier Universitaire, Dijon, France e Department of Diabetes & Endocrinology, Royal Melbourne Hospital, Melbourne, Australia f CHU Montpellier, Laboratoire de Biochimie, Hopital Lapeyronie, Montpellier, France g Faculty of Medicine, Imperial College, London, W12 0NN, U.K. *Corresponding author: Inserm U1061, Hopital La Colombiere, 39, avenue C. Flahault, BP 34493, 34093 Montpellier Cedex 5, France Tel: +33 499 614 562; Fax: +33 499 614 579; E-mail address: [email protected] § Joint first authors Declaration of interest: No conflict of interest. Paper length: 2863 words Title character count: 67 Abstract: 231 words 3 Tables 1 Abstract The aim of this prospective cohort study was to evaluate the effects of lipid lowering agent (LLA) intake on cognitive function in 6830 community-dwelling elderly persons. Cognitive performance (global cognitive functioning, visual memory, verbal fluency, psychomotor speed and executive function), clinical diagnosis of dementia, and fibrate and statin use, were evaluated at baseline, and 2, 4, and 7 year follow-up. Multivariate Cox models were stratified by gender and adjusted for sociodemographic characteristics, mental and physical health including vascular risk factors, and genetic vulnerability (apolipoprotein E and cholesteryl ester transfer protein). -

UMHS Guideline Screening and Management of Lipids

Guidelines for Clinical Care Quality Department Ambulatory Lipid Therapy Screening and Management of Lipids Guideline Team Team Leader Patient population: Adults age 20–79 years without familial or severe dyslipidemias or chronic Audrey L. Fan, MD kidney disease (CKD). (In patients with CKD, see UMHS Management of Chronic Kidney Disease.) General Medicine Objective: Primary and secondary prevention of atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease (ASCVD) Team Members through lipid screening, determining treatment benefit and risk, and providing appropriate treatment. Jill N. Fenske, MD Family Medicine Key Points R. Van Harrison, PhD Obtain a screening / baseline lipid profile Medical Education Patients. Men age ≥ 35 and women age ≥ 45 years. Also men age 20–35 and women age 20–45 who are Melvyn Rubenfire, MD at increased risk for ASCVD [IC*]. Can also consider a screening or baseline lipid profile in adults Cardiology age ≥ 20 when assessing traditional ASCVD risk factors (age, sex, total cholesterol, HDL-C, systolic Marie A. Marcelino, BP, use of antihypertensive therapy, diabetes, and smoking) [IIC*]. PharmD Fasting/non-fasting. Screening lipid profile can be obtained fasting or non-fasting. Pharmacy Services Prior to considering drug treatment for dyslipidemias at any age exclude secondary causes (Table 1). Consultant, 2020 revision Assess ASCVD risk. Does the patient have any of the following risk factors? Trisha D. Wells, PharmD Clinical ASCVD. This includes stroke/TIA, carotid and peripheral arterial disease, and clinical evidence Pharmacy Services of coronary heart disease. Initial Release LDL-C ≥ 190 mg/dL and age ≥ 20, not caused by drugs or an underlying medical condition (Table 1). May 2000 Diabetes mellitus type 1 or 2, and age 40–75 years, with LDL-C 70–189 mg/dL. -

Metabolic Regulation by Lipid Activated Receptors by Maxwell A

Metabolic Regulation by Lipid Activated Receptors By Maxwell A Ruby A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy In Molecular & Biochemical Nutrition In the Graduate Division Of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in charge: Professor Marc K. Hellerstein, Chair Professor Ronald M. Krauss Professor George A. Brooks Professor Andreas Stahl Fall 2010 Abstract Metabolic Regulation by Lipid Activated Receptors By Maxwell Alexander Ruby Doctor of Philosophy in Molecular & Biochemical Nutrition University of California, Berkeley Professor Marc K. Hellerstein, Chair Obesity and related metabolic disorders have reached epidemic levels with dire public health consequences. Efforts to stem the tide focus on behavioral and pharmacological interventions. Several hypolipidemic pharmaceutical agents target endogenous lipid receptors, including the peroxisomal proliferator activated receptor α (PPAR α) and cannabinoid receptor 1 (CB1). To further the understanding of these clinically relevant receptors, we elucidated the biochemical basis of PPAR α activation by lipoprotein lipolysis products and the metabolic and transcriptional responses to elevated endocannabinoid signaling. PPAR α is activated by fatty acids and their derivatives in vitro. While several specific pathways have been implicated in the generation of PPAR α ligands, we focused on lipoprotein lipase mediated lipolysis of triglyceride rich lipoproteins. Fatty acids activated PPAR α similarly to VLDL lipolytic products. Unbound fatty acid concentration determined the extent of PPAR α activation. Lipolysis of VLDL, but not physiological unbound fatty acid concentrations, created the fatty acid uptake necessary to stimulate PPAR α. Consistent with a role for vascular lipases in the activation of PPAR α, administration of a lipase inhibitor (p-407) prevented PPAR α dependent induction of target genes in fasted mice. -

Global Hypercoagulability in Patients with Schizophrenia Receiving Long-Term Antipsychotic Therapy

Schizophrenia Research 162 (2015) 175–182 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Schizophrenia Research journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/schres Global hypercoagulability in patients with schizophrenia receiving long-term antipsychotic therapy Vincent Chow a,b,c,CarolineReddela,b,c, Gabrielle Pennings a,b,c, Elizabeth Scott d,TundraPasqualone, Austin C.C. Ng b,c,ThomasYeohb, Jennifer Curnow a,c,f, Leonard Kritharides a,b,c,⁎ a ANZAC Research Institute, Sydney, Australia b Department of Cardiology, Concord Repatriation General Hospital, Sydney Local Health District, Sydney, Australia c University of Sydney, Australia d Brain & Mind Research Institute, University of Sydney, Australia e Department of Psychiatry, Croydon Health Centre, Sydney, Australia f Department of Haematology, Concord Repatriation General Hospital, Sydney Local Health District, Sydney, Australia article info abstract Article history: Background: Patients with schizophrenia are at increased risk of venous thromboembolism. The mechanisms Received 21 January 2014 underlying this association are poorly understood. Received in revised form 4 December 2014 Aims: We investigated whether there is a global hypercoagulable state in patients with schizophrenia utilising the Accepted 6 December 2014 overall haemostatic potential (OHP) assay which assesses overall coagulation potential (OCP), haemostatic Available online 27 January 2015 potential (OHP) and fibrinolytic potential (OFP). Method: Citrated plasma was collected for OHP assays from patients with schizophrenia on long-term antipsy- Keywords: chotic treatment and compared with healthy age- and sex-matched controls. Time courses of fibrin formation Schizophrenia Blood coagulation test and degradation were measured by spectrophotometry (absorption of 405 nm) after the addition of tissue factor Coagulation and tissue plasminogen activator to plasma. -

Repression of Glucocorticoid-Stimulated Angiopoietin-Like 4 Gene Transcription by Insulin

Repression of glucocorticoid-stimulated angiopoietin-like 4 gene transcription by insulin Taiyi Kuo , * ,† Tzu-Chieh Chen , † Stephanie Yan , † Fritz Foo , † Cecilia Ching , † Allison McQueen , † and Jen-Chywan Wang 1, * ,† Endocrinology Graduate Program* and Department of Nutritional Sciences & Toxicology, † University of California, Berkeley , Berkeley, CA 94720-3104 Abstract Angiopoietin-like 4 (Angptl4) is a glucocorticoid re- into monoacylglycerol and FFAs, which can then be taken Downloaded from ceptor (GR) primary target gene in hepatocytes and adipo- up into the cells. Angptl4 can also induce lipolysis in adi- cytes. It encodes a secreted protein that inhibits extracellular pocytes ( 1–4 ). For adipocytes, the net metabolic effect of LPL and promotes adipocyte lipolysis. In Angptl4 null mice, Angptl4 is to mobilize lipids to plasma. The importance of glucocorticoid-induced adipocyte lipolysis and hepatic ste- Angptl4 in the regulation of lipid homeostasis is supported atosis are compromised. Markedly, insulin suppressed glucocorticoid-induced Angptl4 transcription. To unravel the by a series of physiological studies (2, 5 ). First, injecting www.jlr.org mechanism, we utilized small molecules to inhibit insulin ANGPTL4 recombinant proteins rapidly increases plasma signaling components and found that phosphatidylinositol TG and FFA levels ( 5, 6 ). Mice overexpressing Angptl4 in 3-kinase and Akt were vital for the suppression in H4IIE cells. muscle and adipose tissue have increased plasma TG levels at Univ of Calif Lib Biosciences Natural Res, on April 28, 2014 A forkhead box transcription factor response element ( FRE ) ( 7 ), and adenoviral-mediated overexpression of Angptl4 in was found near the 15 bp Angptl4 glucocorticoid response ele- liver causes hyperlipidemia and hepatic steatosis ( 8 ). -

Treatment Strategy for Dyslipidemia in Cardiovascular Disease Prevention: Focus on Old and New Drugs

pharmacy Article Treatment Strategy for Dyslipidemia in Cardiovascular Disease Prevention: Focus on Old and New Drugs Donatella Zodda 1,*, Rosario Giammona 2 and Silvia Schifilliti 2 1 Drug Department of Local Health Unit (ASP), Viale Giostra, 98168 Messina, Italy 2 Clinical Pharmacy Fellowship, University of Messina, Viale Annunziata, 98168 Messina, Italy; [email protected] (R.G.); silvia.schifi[email protected] (S.S.) * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +39-090-3653902 Received: 12 November 2017; Accepted: 11 January 2018; Published: 21 January 2018 Abstract: Prevention and treatment of dyslipidemia should be considered as an integral part of individual cardiovascular prevention interventions, which should be addressed primarily to those at higher risk who benefit most. To date, statins remain the first-choice therapy, as they have been shown to reduce the risk of major vascular events by lowering low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C). However, due to adherence to statin therapy or statin resistance, many patients do not reach LDL-C target levels. Ezetimibe, fibrates, and nicotinic acid represent the second-choice drugs to be used in combination with statins if lipid targets cannot be reached. In addition, anti-PCSK9 drugs (evolocumab and alirocumab) provide an effective solution for patients with familial hypercholesterolemia (FH) and statin intolerance at very high cardiovascular risk. Recently, studies demonstrated the effects of two novel lipid-lowering agents (lomitapide and mipomersen) for the management of homozygous FH by decreasing LDL-C values and reducing cardiovascular events. However, the costs for these new therapies made the cost–effectiveness debate more complicated. Keywords: lipid lowering therapy; dyslipidemia; statins; fibrate; PCSK9 inhibitors; lomitapide 1. -

NLA Task Force on Statin Safety - 2014 Update

Journal of Clinical Lipidology (2014) 8, S1–S4 Executive Summary NLA Task Force on Statin Safety - 2014 update Terry A. Jacobson, MD, FNLA, Chair, The NLA Task Force on Statin Safety - 2014 Update* Department of Medicine, Office of Health Promotion and Disease Prevention, Emory University, 49 Jesse Hill Jr Drive SE, Atlanta, GA 30303, USA KEYWORDS: Statins; Statin drug; Statin muscle; Statin intolerance; Statin brain; Statin liver; Statin diabetes Statins are the most widely prescribed class of medications classified into these risk categories. Although shocking, in the United States and their benefits for lowering low- these numbers do not even account for the hundreds of mil- density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C) and reducing the lions of patients who qualify for statins because they risk for coronary heart disease (CHD) are well docu- already have ASCVD, diabetes mellitus, or extremely mented.1 Statins have been the cornerstone of pharmaco- high LDL-C levels. Therefore, the potential risks and ben- therapy for the management of high blood cholesterol efits of statin use are a major US and worldwide public levels virtually since their development. The American health concern. Heart Association /American College of Cardiology 2013 In 2006, the National Lipid Association (NLA) guidelines recently expanded the number of individuals convened a Statin Safety Assessment Task Force of experts eligible for statin therapy by recommending it for those who published their findings on specific questions related to with: (1) clinical atherosclerotic -

STATIN-FIBRATE REPORT: Focus on Safety VHA Pharmacy Benefits Management-Strategic Healthcare Group and the Medical Advisory Panel

Statin-Fibrate Safety Report-Final STATIN-FIBRATE REPORT: Focus on Safety VHA Pharmacy Benefits Management-Strategic Healthcare Group and The Medical Advisory Panel Executive Summary: (Key Questions) Efficacy a. Is there evidence to demonstrate an advantage with regard to reducing coronary health outcomes in patients receiving a combination of statins plus fibrates compared to statins alone (e.g. especially in patients with TG in the 300 range-metabolic syndrome) to justify the risk of the combination? At this time, there is a lack of evidence to support a reduction in coronary health outcomes with the statin-fibrate combination. The LDS study would have helped answer this question but was stopped due to withdrawal of cerivastatin from the market. The ACCORD study will have in excess of 5000 patients with type 2 diabetes on the combination of fenofibrate plus simvastatin vs. simvastatin alone. The primary outcome measures in this trial will include nonfatal myocardial infarction and nonfatal stroke, cardiovascular death and overall mortality. However, data from ACCORD will not be available until 2008 or 2009. b. Which fibrates (e.g. fenofibrate or gemfibrozil) have evidence to support their benefit in reducing coronary heart disease health outcomes when used as monotherapy? To summarize, when evaluated in primary prevention (WHO study), clofibrate was associated with a reduction in the risk for nonfatal MI. However, an excess in total mortality was also observed in the clofibrate group compared to placebo. This increase was attributed to deaths from diseases of the liver, intestines and gallbladder. In secondary prevention (CDP study), clofibrate was not significantly different from placebo with regard to reducing coronary heart disease (CHD) events.