Loggers and the Struggle for Development in Newfoundland

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Estateestate AUCTION Due to the Passing of Joe Penrod Will Sell the Following Located 1 Mile North of Gravois Mills, Mo., on Hwy

SAMSAM CRAWFORDCRAWFORD AUCTIONAUCTION SERVICE,SERVICE, LLCLLC EstateEstate AUCTION Due to the passing of Joe Penrod will sell the following located 1 mile North of Gravois Mills, Mo., on Hwy. 5 to Hwy. TT, then East 1/4 mile. Watch for Crawford Auction Service signs. saturday, apr. 14, 2018—9:30 a.m. H REAL ESTATE H VEHICLES H TOOLS H ANTIQUES H MISCELLANEOUS See website for more photos REAL ESTATE SELLS AT 12 NOON 2-Bedroom, 2-bath partial earth contact home with 2-room loft on top. Central heat and air, fireplace, well and septic. 24’x24’ (approx.) block shop/garage TOOLS, MISCELLANEOUS building, enclosed metal carport, all on 2.8 acres. Great lake location just Craftsman 10” table saw Used tires and wheels; Diebold safe, 6’ tall 2 Delta 10” table saws Metal job box; Air hammer with accessories north of Gravois Mills and close to entrance of Jacob’s Cave. Wards 10” radial arm saw 4-5 Plastic folding tables; Wards gas heater Grizzly industrial combination sander Ashley fireplace insert Heirs live out of area and want to sell. Make plans to be a buyer day of sale. Grizzly edge sander; Older grizzly planer 5-6 Pieces square tubing, 2” wide, Shown by appointment with auctioneer Rockwell band saw; Tile saw; Drill press 16’-18’ long 2 Belsaw sharpeners Some metal roofing; 2 Pop-up canopies Small Craftsman metal lathe Roll insulated vinyl , mateiral Craftsman 12” wood lathe Fiberglass storage box; 5-Gal. propane tank Wards metal lathe; Metal band saw 100# Propane bottle; Gas cans; ANTIQUES, 2 Cut off saws; Miter saw Extension cords; Garden -

2008 Agreement for the Recognition of The

November 30, 2007 Agreement for the Recognition of the Qalipu Mi’kmaq Band FNI DOCUMENT 2007 NOVEMBER 30, 1 November 30, 2007 Table of Contents Parties and Preamble...................................................................................................... 3 Chapter 1 Definitions....................................................................................................... 4 Chapter 2 General Provisions ......................................................................................... 7 Chapter 3 Band Recognition and Registration .............................................................. 13 Chapter 4 Eligibility and Enrolment ............................................................................... 14 Chapter 5 Federal Programs......................................................................................... 21 Chapter 6 Governance Structure and Leadership Selection ......................................... 21 Chapter 7 Applicable Indian Act Provisions................................................................... 23 Chapter 8 Litigation Settlement, Release and Indemnity............................................... 24 Chapter 9 Ratification.................................................................................................... 25 Chapter 10 Implementation ........................................................................................... 28 Signatures ..................................................................................................................... 30 -

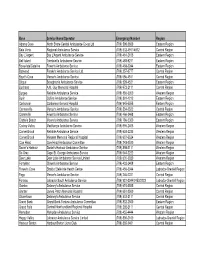

Revised Emergency Contact #S for Road Ambulance Operators

Base Service Name/Operator Emergency Number Region Adams Cove North Shore Central Ambulance Co-op Ltd (709) 598-2600 Eastern Region Baie Verte Regional Ambulance Service (709) 532-4911/4912 Central Region Bay L'Argent Bay L'Argent Ambulance Service (709) 461-2105 Eastern Region Bell Island Tremblett's Ambulance Service (709) 488-9211 Eastern Region Bonavista/Catalina Fewer's Ambulance Service (709) 468-2244 Eastern Region Botwood Freake's Ambulance Service Ltd. (709) 257-3777 Central Region Boyd's Cove Mercer's Ambulance Service (709) 656-4511 Central Region Brigus Broughton's Ambulance Service (709) 528-4521 Eastern Region Buchans A.M. Guy Memorial Hospital (709) 672-2111 Central Region Burgeo Reliable Ambulance Service (709) 886-3350 Western Region Burin Collins Ambulance Service (709) 891-1212 Eastern Region Carbonear Carbonear General Hospital (709) 945-5555 Eastern Region Carmanville Mercer's Ambulance Service (709) 534-2522 Central Region Clarenville Fewer's Ambulance Service (709) 466-3468 Eastern Region Clarke's Beach Moore's Ambulance Service (709) 786-5300 Eastern Region Codroy Valley MacKenzie Ambulance Service (709) 695-2405 Western Region Corner Brook Reliable Ambulance Service (709) 634-2235 Western Region Corner Brook Western Memorial Regional Hospital (709) 637-5524 Western Region Cow Head Cow Head Ambulance Committee (709) 243-2520 Western Region Daniel's Harbour Daniel's Harbour Ambulance Service (709) 898-2111 Western Region De Grau Cape St. George Ambulance Service (709) 644-2222 Western Region Deer Lake Deer Lake Ambulance -

Total of 10 Pages Only May Be Xeroxed

A GRAVITY SU VEY A ERN NOTR BAY, N W UNDLAND CENTRE FOR NEWFOUNDLAND STUDIES TOTAL OF 10 PAGES ONLY MAY BE XEROXED (Without Author's Permission) HUGH G. Ml rt B. Sc. (HOI S.) ~- ··- 223870 A GRAVITY SURVEY OF EASTERN NOTRE DAME BAY, NEWFOUNDLAND by @ HUGH G. MILLER, B.Sc. {HCNS.) .. Submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science, Memorial University of Newfoundland. July 20, 1970 11 ABSTRACT A gravity survey was undertaken on the archipelago and adjacent coast of eastern Notre Dame Bay, Newfoundland. A total of 308 gravity stations were occupied with a mean station spacing of 2,5 km, and 9 gravity sub-bases were established. Elevations for the survey were determined by barometric and direct altimetry. The densities of rock samples collected from 223 sites were detenmined. A Bouguer anomaly map was obtained and a polynomial fitting technique was employed to determine the regional contribution to the total Bouguer anomaly field. Residual and regional maps based on a fifth order polynomial were obtained. Several programs were written for the IBM 360/40 computer used in this and model work. Three-dimensional model studies were carried out and a satisfactory overall fit to the total Bouguer field was obtained. Several shallow features of the anomaly maps were found to correlate well with surface bodies, i.e. granite or diorite bodies. Sedimentary rocks had little effect on the gravity field. The trace of the Luke's Arm fault was delineated. The following new features we r~ discovered: (1) A major structural discontinuity near Change Islands; (2) A layer of relatively high ·density (probably basic to ultrabasic rock) at 5 - 10 km depth. -

Newfoundland in International Context 1758 – 1895

Newfoundland in International Context 1758 – 1895 An Economic History Reader Collected, Transcribed and Annotated by Christopher Willmore Victoria, British Columbia April 2020 Table of Contents WAYS OF LIFE AND WORK .................................................................................................................. 4 Fog and Foundering (1754) ............................................................................................................................ 4 Hostile Waters (1761) .................................................................................................................................... 4 Imports of Salt (1819) .................................................................................................................................... 5 The Great Fire of St. John’s (1846) ................................................................................................................. 5 Visiting Newfoundland’s Fisheries in 1849 (1849) .......................................................................................... 9 The Newfoundland Seal Hunt (1871) ........................................................................................................... 15 The Inuit Seal Hunt (1889) ........................................................................................................................... 19 The Truck, or Credit, System (1871) ............................................................................................................. 20 The Preparation of -

Prince Edward Island

AIMS 4TH ANNUAL HIGH SCHOOL REPORT CARD (RC4) Newfoundland and Labrador High Schools Newfoundland and Labrador continues to provide the widest set of measures in the region of both achievement and engagement. A particularly strong system of standardized provincial examinations allowed us to calculate a rich set of achievement measures. In the current Report Card, we expanded our assessed measures to include school-assigned grades. Overall, no school achieved an A, and, similarly, no school achieved a failing grade. Because of gaps in data availability, we only were able to provide overall rankings for 74 schools in the province; however, in keeping with past practice, AIMS will release whatever valid data we have been able to secure for every school at www.aims.ca. The province’s leading school is Lakeside Academy, which earned an overall grade of B+’ following up on its strong A in the previous Report Card. Several schools made considerable improvements over the past year, with Point Leamington Academy, Roncalli Central High and Smallwood Academy improving from C+ to B+, respectively. Gonzaga High School was the highest-ranked school in St. John’s, earning a B, with a particularly strong absolute performance. At the bottom of the table, several schools moving in opposite directions. Jane Collins High School improved from an F to a C. In contrast, St. Michael’s Regional High fell from a C to a D, and Mobile Central High dropped from a B to a C. RC4 RC4 RC3 RC4 Absolute RC4 Overall Final Final Final Overall Performance Rank Grade Grade School Name and Location Performance in Context 1 B+ A Lakeside Academy, Buchans B+ A 2 B+ B Dorset Collegiate, Pilley's Island B+ A 3 B+ A Pasadena Academy, Pasadena B+ B+ 4 B+ A Burgeo Academy, Burgeo A B 5 B+ C+ Point Leamington Academy, Point Leamington B+ B+ 6 B+ B+ Glovertown Academy, Glovertown B+ B+ 7 B+ C+ Smallwood Academy, Gambo B+ B+ 8 B+ B John Burke High School, Grand Bank B+ B+ 9 B+ B+ Lester Pearson Memorial High, Wesleyville B+ B 10 B+ B St. -

Csc-Rmjpc -1906

ARCHIVED - Archiving Content ARCHIVÉE - Contenu archivé Archived Content Contenu archivé Information identified as archived is provided for L’information dont il est indiqué qu’elle est archivée reference, research or recordkeeping purposes. It est fournie à des fins de référence, de recherche is not subject to the Government of Canada Web ou de tenue de documents. Elle n’est pas Standards and has not been altered or updated assujettie aux normes Web du gouvernement du since it was archived. Please contact us to request Canada et elle n’a pas été modifiée ou mise à jour a format other than those available. depuis son archivage. Pour obtenir cette information dans un autre format, veuillez communiquer avec nous. This document is archival in nature and is intended Le présent document a une valeur archivistique et for those who wish to consult archival documents fait partie des documents d’archives rendus made available from the collection of Public Safety disponibles par Sécurité publique Canada à ceux Canada. qui souhaitent consulter ces documents issus de sa collection. Some of these documents are available in only one official language. Translation, to be provided Certains de ces documents ne sont disponibles by Public Safety Canada, is available upon que dans une langue officielle. Sécurité publique request. Canada fournira une traduction sur demande. 6-7 EDWARD VII. SESSIONAL PAPER No. 34 A. 1907 REPORT OF THE MINISTER OF JUSTICE AS TO PENITENTIARIES 0 Er CANADA FOR THE YEAR ENDE D JUN E 80 1906 P.RINTED BY ORDER OF PARLIAMENT OTTAWA PRINTED BY S. E. DAWSON, PRINTER TO THE KING'S MOST EXCELLENT MAJESTY 1907 ]No. -

The Hitch-Hiker Is Intended to Provide Information Which Beginning Adult Readers Can Read and Understand

CONTENTS: Foreword Acknowledgements Chapter 1: The Southwestern Corner Chapter 2: The Great Northern Peninsula Chapter 3: Labrador Chapter 4: Deer Lake to Bishop's Falls Chapter 5: Botwood to Twillingate Chapter 6: Glenwood to Gambo Chapter 7: Glovertown to Bonavista Chapter 8: The South Coast Chapter 9: Goobies to Cape St. Mary's to Whitbourne Chapter 10: Trinity-Conception Chapter 11: St. John's and the Eastern Avalon FOREWORD This book was written to give students a closer look at Newfoundland and Labrador. Learning about our own part of the earth can help us get a better understanding of the world at large. Much of the information now available about our province is aimed at young readers and people with at least a high school education. The Hitch-Hiker is intended to provide information which beginning adult readers can read and understand. This work has a special feature we hope readers will appreciate and enjoy. Many of the places written about in this book are seen through the eyes of an adult learner and other fictional characters. These characters were created to help add a touch of reality to the printed page. We hope the characters and the things they learn and talk about also give the reader a better understanding of our province. Above all, we hope this book challenges your curiosity and encourages you to search for more information about our land. Don McDonald Director of Programs and Services Newfoundland and Labrador Literacy Development Council ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I wish to thank the many people who so kindly and eagerly helped me during the production of this book. -

United States National Museum

SMITHSONIAN INSTITUTION UNITED STATES NATIONAL MUSEUM BULLETIN 2 30 WASHINGTON, D.C. 1964 MUSEUM OF HISTORY AND TECHNOLOGY The Bark Canoes and Skin Boats of North America Edwin Tappan Adney and Howard I. Chapelle Curator of Transportation SMITHSONIAN INSTITUTION, WASHINGTON, D.C. 1964 — Publications of the United States National Aiuseum The scholarly and scientific publications of the United States National Museum include two series, Proceedings of the United States National Museum and United States National Museum Bulletin. In these series the Museum publishes original articles and monographs dealing with the collections and work of its constituent museums—The Museum of Natural History and the Museum of History and Technology setting forth newly acquired facts in the fields of Anthropology, Biology, History, Geology, and Technology. Copies of each publication are distributed to libraries, to cultural and scientific organizations, and to specialists and others interested in the different subjects. The Proceedings, begun in 1878, are intended for the publication, in separate form, of shorter papers from the Museum of Natural History. These are gathered in volumes, octavo in size, with the publication date of each paper recorded in the table of contents of the volume. In the Bulletin series, the first of which was issued in 1875, appear longer, separate publications consisting of monographs (occasionally in several parts) and volumes in which are collected works on related subjects. Bulletins are either octavo or quarto in size, depending on the needs of the presentation. Since 1902 papers relating to the botanical collections of the Museum of Natural History have been published in the Bulletin series under the heading Contributions Jrom the United States National Herbarium, and since 1959, in Bulletins titled "Contributions from the Museum of History and Technology," have been gathered shorter papers relating to the collections and research of that Museum. -

6111010Mommollt-Slilinfintimo Vann ! I I Vol. LXII April 21, 1914 Mamma

mamma 7ammilimm mum ip mum MUM* UMW riFF5107611Ho MUMMIIMI1 -4i- MEM mummmr4 immis1 11111111111111111111 111111111111111111r 4- +4, The YOUTH'S I INSTRUCTOR 4...0.610.m..... .4 ..•••••••401.1•40.••••••••••••••+.4•4400.•=4+.••44..••• •= 04 • Vol. LXII April 21, 1914 aarmasfmno+omm.rmw+amovii.m.4.. .....E......m."..m.. ..... ..pana+mort r•m4laim+.4«mo !I I • L6111010mommollt-slilinfintimop__ 11111111111U1 4p AMMAN sothoto 111111111111111111 L1--4111111111171111 E Vann MUUNipAINIIIMILIAMMHM MUNI THERE are approximately 3,500 languages or dialects banks and post-office savings departments to save. The in the world. people are beginning to show a bent toward industry. In the old days there was no inducement for them to OVER 6,000,000 acres of land are under tobacco cul- make more than a bare living, since greedy officials tivation throughout the world. always appropriated the surplus. Under the new re- ONE ton of cork occupies a space of 15o cubic feet ; gime. by means of agricultural schools, model agri- a ton of gold, that of two cubic feet. cultural and industrial farms, cotton planting stations, seedling stations, and sericulture stations, the farmers THERE died in America during last year, according are being assisted to raise more and better crops. to records compiled by the Journal of the American Fruit does especially well in Korea, and already one Medical Association, 2,196 physicians. may secure apples, grapes, and pears in great quan- THE salt beds of Chile alone could supply the tities. The increase in the rice crop is about twenty- world with salt for ages to come, the mineral being five per cent a year ; wheat and barley, forty per cent found in large deposits 99 per cent pure. -

Intact Habitat Landscapes and Woodland Caribou on the Island of Newfoundland a Bulletin Produced by the Canadian Boreal Initiative

November 2011 Intact Habitat Landscapes and Woodland Caribou on the Island of Newfoundland A bulletin produced by the Canadian Boreal Initiative AutHors ÂÂ Dr. Jeffrey Wells, Science Advisor to the International Boreal Conservation Campaign ÂÂ Dr. John Jacobs, President of Nature Newfoundland and Labrador ÂÂ Dr. Ian Goudie, Forest Issues Coordinator at the Canadian Parks and Wilderness Society of Newfoundland and Labrador ÂÂ Jonathan Feldgajer, Regional Advisor to the Canadian Boreal Initiative CBI wishes to thank Peter Lee and Ryan Cheng at Global Forest Watch Canada for the mapping work in this report. The Canadian Boreal Initiative (CBI) brings together diverse partners to create new solutions for boreal conservation and sustainable development. It acts as a catalyst for on-the-ground efforts across the Boreal Forest region by governments, industry, Aboriginal communities, conservation groups, major retailers, financial institutions and scientists. suggested citation: Wells, J., J. Jacobs, I. Goudie and J. Feldgajer. 2011. Intact Habitat Landscapes and Woodland Caribou on the Island of Newfoundland. Canadian Boreal Initiative, Ottawa, Canada. 1 Intact Habitat Landscapes and Woodland Caribou on the Island of Newfoundland November 2011 ExecutIvE summAry Woodland caribou in Newfoundland have recently experienced a steep and rapid decline. While predation on caribou calves is a key reason for this decline, habitat alteration from human land use and activities can result in functional habitat loss – a decline in caribou occupancy well beyond the immediate footprint of the disturbance. Disturbed areas also allow predators easier access to caribou herds. Newfoundland’s caribou occupy large, intact landscapes within which there are core areas important for calving and wintering. -

Review of Applications for Membership in the Qalipu Mi'kmaq First Nation Band Important Information for Applicants July 2013

IMPORTANT INFORMATION FOR APPLICANTS JULY 2013 REVIEW OF APPLICATIONS FOR MEMBERSHIP IN THE QALIPU MI’KMAQ FIRST NATION BAND Note: Applicants are advised that this document is not a substitute for the June 2013 Supplemental Agreement, the June 2013 Directive to the Enrolment Committee, or the 2008 Agreement. This Information Update is intended to provide general guidelines on what information applicants can start to gather to support their application for enrolment in the Qalipu Mi’kmaq First Nation. On July 4, 2013, Canada and the Federation of Newfoundland Indians (FNI) announced a Supplemental Agreement that clarifies the process for enrolment in the Qalipu Mi’kmaq First Nation and resolves issues that emerged in the implementation of the 2008 Agreement. All applications submitted between December 1, 2008, and November 30, 2012, except those previously rejected, will be reviewed to ensure that applicants meet the criteria for eligibility set out in the 2008 Agreement. This includes the applications of all those who have gained Indian status as members of the Qalipu Mi’kmaq First Nation. No new applications will be accepted. In November 2013, all applicants, except those Checklist previously rejected, will be sent a letter. Where an application is invalid, the letter will advise applicants that Ensure your address is up to date (Section A) their application is denied. Where an application is valid, Provide birth certificate, and proof of the letter will outline general documentation and request, by September 3, 2013 (Section B) informational requirements as well as where to send additional information applicants may wish to submit. It Understand Requirements to support is the sole responsibility of applicants to determine what self-identification (Section C) additional documentation they wish to submit in support Gather documents to support demonstration of their applications.