Introduction Structure and Development

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Barking up the Same Tree: a Comparison of Ethnomedicine and Canine Ethnoveterinary Medicine Among the Aguaruna Kevin a Jernigan

Journal of Ethnobiology and Ethnomedicine BioMed Central Research Open Access Barking up the same tree: a comparison of ethnomedicine and canine ethnoveterinary medicine among the Aguaruna Kevin A Jernigan Address: COPIAAN (Comité de Productores Indígenas Awajún de Alto Nieva), Bajo Cachiaco, Peru Email: Kevin A Jernigan - [email protected] Published: 10 November 2009 Received: 9 July 2009 Accepted: 10 November 2009 Journal of Ethnobiology and Ethnomedicine 2009, 5:33 doi:10.1186/1746-4269-5-33 This article is available from: http://www.ethnobiomed.com/content/5/1/33 © 2009 Jernigan; licensee BioMed Central Ltd. This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited. Abstract Background: This work focuses on plant-based preparations that the Aguaruna Jivaro of Peru give to hunting dogs. Many plants are considered to improve dogs' sense of smell or stimulate them to hunt better, while others treat common illnesses that prevent dogs from hunting. This work places canine ethnoveterinary medicine within the larger context of Aguaruna ethnomedicine, by testing the following hypotheses: H1 -- Plants that the Aguaruna use to treat dogs will be the same plants that they use to treat people and H2 -- Plants that are used to treat both people and dogs will be used for the same illnesses in both cases. Methods: Structured interviews with nine key informants were carried out in 2007, in Aguaruna communities in the Peruvian department of Amazonas. -

Bark Anatomy and Cell Size Variation in Quercus Faginea

Turkish Journal of Botany Turk J Bot (2013) 37: 561-570 http://journals.tubitak.gov.tr/botany/ © TÜBİTAK Research Article doi:10.3906/bot-1201-54 Bark anatomy and cell size variation in Quercus faginea 1,2, 2 2 2 Teresa QUILHÓ *, Vicelina SOUSA , Fatima TAVARES , Helena PEREIRA 1 Centre of Forests and Forest Products, Tropical Research Institute, Tapada da Ajuda, 1347-017 Lisbon, Portugal 2 Centre of Forestry Research, School of Agronomy, Technical University of Lisbon, Tapada da Ajuda, 1349-017 Lisbon, Portugal Received: 30.01.2012 Accepted: 27.09.2012 Published Online: 15.05.2013 Printed: 30.05.2013 Abstract: The bark structure of Quercus faginea Lam. in trees 30–60 years old grown in Portugal is described. The rhytidome consists of 3–5 sequential periderms alternating with secondary phloem. The phellem is composed of 2–5 layers of cells with thin suberised walls and narrow (1–3 seriate) tangential band of lignified thick-walled cells. The phelloderm is thin (2–3 seriate). Secondary phloem is formed by a few tangential bands of fibres alternating with bands of sieve elements and axial parenchyma. Formation of conspicuous sclereids and the dilatation growth (proliferation and enlargement of parenchyma cells) affect the bark structure. Fused phloem rays give rise to broad rays. Crystals and druses were mostly seen in dilated axial parenchyma cells. Bark thickness, sieve tube element length, and secondary phloem fibre wall thickness decreased with tree height. The sieve tube width did not follow any regular trend. In general, the fibre length had a small increase toward breast height, followed by a decrease towards the top. -

Plant Mobility in the Mesozoic Disseminule Dispersal Strategies Of

Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology 515 (2019) 47–69 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/palaeo Plant mobility in the Mesozoic: Disseminule dispersal strategies of Chinese and Australian Middle Jurassic to Early Cretaceous plants T ⁎ Stephen McLoughlina, , Christian Potta,b a Palaeobiology Department, Swedish Museum of Natural History, Box 50007, 104 05 Stockholm, Sweden b LWL - Museum für Naturkunde, Westfälisches Landesmuseum mit Planetarium, Sentruper Straße 285, D-48161 Münster, Germany ARTICLE INFO ABSTRACT Keywords: Four upper Middle Jurassic to Lower Cretaceous lacustrine Lagerstätten in China and Australia (the Daohugou, Seed dispersal Talbragar, Jehol, and Koonwarra biotas) offer glimpses into the representation of plant disseminule strategies Zoochory during that phase of Earth history in which flowering plants, birds, mammals, and modern insect faunas began to Anemochory diversify. No seed or foliage species is shared between the Northern and Southern Hemisphere fossil sites and Hydrochory only a few species are shared between the Jurassic and Cretaceous assemblages in the respective regions. Free- Angiosperms sporing plants, including a broad range of bryophytes, are major components of the studied assemblages and Conifers attest to similar moist growth habitats adjacent to all four preservational sites. Both simple unadorned seeds and winged seeds constitute significant proportions of the disseminule diversity in each assemblage. Anemochory, evidenced by the development of seed wings or a pappus, remained a key seed dispersal strategy through the studied interval. Despite the rise of feathered birds and fur-covered mammals, evidence for epizoochory is minimal in the studied assemblages. Those Early Cretaceous seeds or detached reproductive structures bearing spines were probably adapted for anchoring to aquatic debris or to soft lacustrine substrates. -

Tree Identification: from Bark and Leaves Or Needles

Tree Identification: from bark and leaves or needles A walk in the woods can be a lot of fun, especially if you bring your kids. How do you get them to come along with you? Tell them this. “Look at the bark on the trees. Can you can find any that look like burnt potato chips, warts, cat scratches, camouflage pants or rippling muscles?” Believe it or not, these are descriptions of different kinds of tree bark. Tree ID from bark:______________________________________________________ Black cherry: The bark looks like burnt potato chips. Hackberry: The bark is bumpy and warty. Ironwood: The bark has long thin strips. With a little imagination, an ironwood can look like it is used as a scratching post by cats. They can also be easily spotted in winter because their light brown dead leaves hang on well past the first snow. Sycamore: A tree with bark that looks like camouflaged pants. The largest tree in Illinois is a sycamore, a majestic 115-foot tree near Springfield. Musclewood: a tree with smooth gray bark covering a trunk with ridges that look like they are rippling muscles. Shagbark hickory: Long strips of shaggy bark peeling at both ends. Cottonwood: Has heavy ridges that make it look like Paul Bunyan’s corduroy pants. Bur oak: Thick and gnarly bark has deep craggy furrows. The corky bark allows it to easily withstand hot forest fires. Tree ID from leaves or needles:________________________________________ Willow Oak: Has elongated leaves similar to those of a willow tree. Red pine: Red has 3 letters; a red pine has groupings of 2-3 prickly needles. -

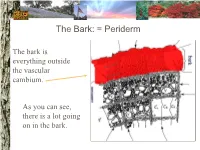

The Bark: = Periderm

The Bark: = Periderm The bark is everything outside the vascular cambium. As you can see, there is a lot going on in the bark. The Bark: periderm: phellogen (cork cambium): The phellogen is the region of cell division that forms the periderm tissues. Phellogen development influences bark appearance. The Bark: periderm: phellem (cork): Phellem replaces the epidermis as the tree increases in girth. Photosynthesis can take place in some trees both through the phellem and in fissures. The Bark: periderm: phelloderm: Phelloderm is active parenchyma tissue. Parenchyma cells can be used for storage, photosynthesis, defense, and even cell division! The Bark: phloem: Phloem tissue makes up the inner bark. However, it is vascular tissue formed from the vascular cambium. The Bark: phloem: sieve tube elements: Sieve tube elements actively transport photosynthates down the stem. Conifers have sieve cells instead. The cambium: The cambium is the primary meristem producing radial growth. It forms the phloem & xylem. The Xylem (wood): The xylem includes everything inside the vascular cambium. The Xylem: a growth increment (ring): The rings seen in many trees represent one growth increment. Growth rings provide the texture seen in wood. The Xylem: vessel elements: Hardwood species have vessel elements in addition to trachieds. Notice their location in the growth rings of this tree The Xylem: fibers: Fibers are cells with heavily lignified walls making them stiff. Many fibers in sapwood are alive at maturity and can be used for storage. The Xylem: axial parenchyma: Axial parenchyma is living tissue! Remember that parenchyma cells can be used for storage and cell division. -

The Dirt January 2019

The Dirt January 2019 A quarterly online magazine published for Master Gardeners in support of the educational mission of UF/IFAS Extension Service. Is it really January? January 2019 Issue 16 By Ellen Mahaney, Master Gardener Is it really January? As I write this article, we have yet to experience frost or freeze, so my Foraging Hubs: Maximizing ecosystem garden looks more like July than January. Year-round blooming plants services in the built landscape such as firebush, plumbago, senna, Simpson's stopper, white indigo, Gardening with Children sparkleberry, trailing lavender lantana, false rosemary, porter weed, rouge plant, bulbine, and coreopsis offer a summery appearance. Seeking a Green Thumb? Grow Some Herbs Several common butterfly species have gone to winter homes further south. However, Monarch and Sulphur butterflies still show up, Around the World in 80 Trees welcomed by their larva plants—sennas for sulphurs and the Pictures from South China Botanical somewhat controversial tropical milkweed (Asclepias curassavica) for Garden monarchs. (Although I did not do so this year, it is advisable to cut International Master Gardener Conference tropical milkweed back in fall.) Master Gardeners Speakers Bureau Send in your articles and photos Senna is a popular larva plant for Sulphur butterflies. Photo credit: Ellen Mahaney. 1 The Dirt January 2019 This is the best time of the year for the dozen or so low maintenance Earth-Kind® and old garden roses in my garden. January brings relief from the long, grueling Florida summer when rose leaves droop like tongues panting in the heat. After a drop in temperatures and an unusual amount of soothing rain during the fall, they bloom profusely, according to their individual cycles. -

Permian–Triassic Non-Marine Algae of Gondwana—Distributions

Earth-Science Reviews 212 (2021) 103382 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Earth-Science Reviews journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/earscirev Review Article Permian–Triassic non-marine algae of Gondwana—Distributions, natural T affinities and ecological implications ⁎ Chris Maysa,b, , Vivi Vajdaa, Stephen McLoughlina a Swedish Museum of Natural History, Box 50007, SE-104 05 Stockholm, Sweden b Monash University, School of Earth, Atmosphere and Environment, 9 Rainforest Walk, Clayton, VIC 3800, Australia ARTICLE INFO ABSTRACT Keywords: The abundance, diversity and extinction of non-marine algae are controlled by changes in the physical and Permian–Triassic chemical environment and community structure of continental ecosystems. We review a range of non-marine algae algae commonly found within the Permian and Triassic strata of Gondwana and highlight and discuss the non- mass extinctions marine algal abundance anomalies recorded in the immediate aftermath of the end-Permian extinction interval Gondwana (EPE; 252 Ma). We further review and contrast the marine and continental algal records of the global biotic freshwater ecology crises within the Permian–Triassic interval. Specifically, we provide a case study of 17 species (in 13 genera) palaeobiogeography from the succession spanning the EPE in the Sydney Basin, eastern Australia. The affinities and ecological im- plications of these fossil-genera are summarised, and their global Permian–Triassic palaeogeographic and stra- tigraphic distributions are collated. Most of these fossil taxa have close extant algal relatives that are most common in freshwater, brackish or terrestrial conditions, and all have recognizable affinities to groups known to produce chemically stable biopolymers that favour their preservation over long geological intervals. -

Hurain, a New Plant Protease from Hura Crepitans A

Reprinted ¡rom THE JOURNAL OF BIOLOGICAL CHEMISTRY Vol. 149, No. 1, J\lly, 1943 HURAIN, A NEW PLANT PRO TEASE FROM HURA CREPITANS By WERNER G. JAFFÉ (From the Department of Chemistry, Instituto Quimio-Biologico, Caracas-Los Rosales, Venezuela) (Received for publication, March 15, 1943) A considerable number of publications exist which describe plant pro• teases, but our knowledge of the chemistry of these enzymes and their mode of action is scant. Except for the ferments of the group of papain• ases, which have been relatively well investigated, there are few experi• mental data on other plant proteases, so that classification outside of this group is, as yet, impossible. In the present papel' some experimental data obtained with a new plant protease are reported which may be helpful for the purpose of classification. Botanical Data-The new ferment was isolated from the sap of the tree Hura crepitans (commonly knO\vn in Venezuela as jabillo) of the family of Euphorbiaceae. Proteases so far have been identified in three members of this family, Croton tiglium, Ricinus communis, and in the sap of Euphorbia palustris (1). EXPERIMENTAL Isolation-vVhen the bark and roots of Hura crepitans are cut, a brown, turbid, and caustic sap appears (which the natives use to remove bad teeth). This sap is slightly acid and has a pH of about 5 to 5.5. Sap isolated dur• ing the dry season yields 20 per cent of residue on drying; during the rainy season, about 17 per cent. It contains no caoutchouc. When centrifuged, the insoluble matter separates slowly and the supernatant liquid becomes clear; this, added to twice its volume of acetone, forms a white precipitate. -

Getting Chemicals Into Trees Without Spraying

Urban Forestry NR/FF/020 (pr) Getting Chemicals Into Trees Without Spraying Michael Kuhns, Forestry Extension Specialist This fact sheet provides an overview of injection, or phellogen that makes cork to thicken the outer bark, implantation, and other ways to get chemicals, mainly phloem that conducts food through the tree from where pesticides, into trees. Many techniques and systems it is stored or made to where it is being used (all of these exist and some are very good, some are good in some tissues together make up the bark), vascular cambium situations, and some are ineffective or bad for trees. that divides rapidly to make new phloem and xylem cells, This fact sheet addresses all of these. and xylem or wood. Xylem includes an outer layer called the sapwood that conducts mostly water and minerals from the roots to the canopy, and an inner layer called the Chemicals are applied to trees for many reasons. heartwood that is aged sapwood that has died and has lost Insecticides repel or kill damaging insects, fungicides its ability to conduct water but still adds strength. treat or prevent fungal diseases, nutrients and plant growth regulators affect growth, and herbicides kill trees or prevent sprouting after tree removal. Spraying is the most typical way to apply these chemicals. It is fast, uses readily available equipment, and is understood. The Phellem (Cork Phellogen down side of spraying is that much of the chemical being or Outer Bark) Phloem applied is wasted, either to drift, run off, or because it can not be applied precisely to where it is needed in the tree. -

Tree Anatomy Stems and Branches

Tree Anatomy Series WSFNR14-13 Nov. 2014 COMPONENTSCOMPONENTS OFOF PERIDERMPERIDERM by Dr. Kim D. Coder, Professor of Tree Biology & Health Care Warnell School of Forestry & Natural Resources, University of Georgia Around tree roots, stems and branches is a complex tissue. This exterior tissue is the environmental face of a tree open to all sorts of site vulgarities. This most exterior of tissue provides trees with a measure of protection from a dry, oxidative, heat and cold extreme, sunlight drenched, injury ridden site. The exterior of a tree is both an ecological super highway and battle ground – comfort and terror. This exterior is unique in its attributes, development, and regeneration. Generically, this tissue surrounding a tree stem, branch and root is loosely called bark. The tissues of a tree, outside or more exterior to the xylem-containing core, are varied and complexly interwoven in a relatively small space. People tend to see and appreciate the volume and physical structure of tree wood and dismiss the remainder of stem, branch and root. In reality, tree life is focused within these more exterior thin tissue sets. Outside of the cambium are tissues which include transport cells, structural support cells, generation cells, and cells positioned to help, protect, and sustain other cells. All of this life is smeared over the circumference of a predominately dead physical structure. Outer Skin Periderm (jargon and antiquated term = bark) is the most external of tree tissues providing protection, water conservation, insulation, and environmental sensing. Periderm is a protective tissue generated over and beyond live conducting and non-conducting cells of the food transport system (phloem). -

Los Géneros De La Familia Euphorbiaceae En México (Parte D) Anales Del Instituto De Biología

Anales del Instituto de Biología. Serie Botánica ISSN: 0185-254X [email protected] Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México México Martínez Gordillo, Martha; Jiménez Ramírez, Jaime; Cruz Durán, Ramiro; Juárez Arriaga, Edgar; García, Roberto; Cervantes, Angélica; Mejía Hernández, Ricardo Los géneros de la familia Euphorbiaceae en México (parte D) Anales del Instituto de Biología. Serie Botánica, vol. 73, núm. 2, julio-diciembre, 2002, pp. 245-281 Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México Distrito Federal, México Disponible en: http://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=40073208 Cómo citar el artículo Número completo Sistema de Información Científica Más información del artículo Red de Revistas Científicas de América Latina, el Caribe, España y Portugal Página de la revista en redalyc.org Proyecto académico sin fines de lucro, desarrollado bajo la iniciativa de acceso abierto GÉNEROS DE EUPHORBIACEAE 245 Fig. 42. Hippomane mancinella. A, rama; B, glándula; C, inflorescencia estaminada (Marín G. 75, FCME). 246 M. MARTÍNEZ GORDILLO ET AL. Se reconoce por tener una glándula en la unión de la lámina y el pecíolo, por el haz, el ovario 6-9-locular y los estilos cortos. Tribu Hureae 46. Hura L., Sp. Pl. 1008. 1753. Tipo: Hura crepitans L. Árboles monoicos; corteza con espinas cónicas; exudado claro. Hojas alternas, simples, hojas usualmente ampliamente ovadas y subcordatas, márgenes serrados, haz y envés glabros o pubescentes; nervadura pinnada; pecíolos largos y con dos glándulas redondeadas al ápice; estípulas pareadas, imbricadas, caducas. Inflorescencias unisexuales, glabras, las estaminadas terminales, largo- pedunculadas, espigadas; bractéolas membranáceas; flor pistilada solitaria en las axilas de las hojas distales. Flor estaminada pedicelada, encerrada en una bráctea delgada que se rompe en la antesis; cáliz unido formando una copa denticulada; pétalos ausentes; disco ausente; estambres numerosos, unidos, filamentos ausen- tes, anteras sésiles, verticiladas y lateralmente compresas en 2-10 verticilos; pistilodio ausente. -

Why Do Animals Eat the Bark and Wood of Trees and Shrubs? William R

FNR-203 Purdue University & Natural Re ry sou Forestry and Natural Resources st rc re e o s F Why Do Animals Eat the Bark and Wood of Trees and Shrubs? William R. Chaney, Professor of Tree Physiology Department of Forestry and Natural Resources Purdue University, West Lafayette, IN 47907 PURDUE UNIVERSITY Animals gnawing the bark and wood of trees anatomy, movement and storage of food in trees, and shrubs is not a malicious act or evidence of a and the variations in digestive systems among neurotic condition. Instead, it is the normal means animals. by which some animals acquire a nutritious food source. The ability to consume this seemingly Constituents of Plant Cell Walls unpalatable food supply and derive nourishment Unlike animals, plants have cells with rigid from it requires specialized feeding habits and cell walls composed of cellulose, hemicellulose, digestive systems. and lignins. Pectins help hold the individual cells together in tissues. All of these substances are potential sources of food for animals. Cellulose The most consummate wood feeders are the A principal component of cell walls is billions of termites throughout the world that cellulose, which consists of 5,000 to 10,000 literally devour thousands of tons of woody glucose molecules joined by a so-called beta debris every year in forests as well as lumber linkage to form straight chain polymers of pure in buildings. Many of our most serious and sugar. The long chains of cellulose are combined damaging insect pests are the bark beetles and first into microfibrils and then further into wood borers that feed on the parts of trees for macrofibrils to create a mesh-like matrix of cell which they are named.