Rural Alberta Homelessness

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

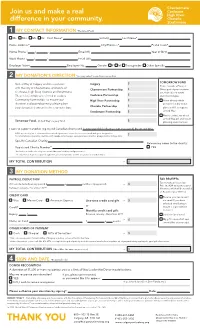

Join Us and Make a Real Difference in Your Community. 3 4

Chestermere Join us and make a real Cochrane High River difference in your community. Okotoks Strathmore 1 MY CONTACT INFORMATION *Required Field Ms. Mrs. Mr. Dr. First Name* Initial(s) Last Name* Home Address* City/Province* Postal Code* Home Phone ( ) - Email (H) Year of Birth Work Phone ( ) - Email (W) Employer Name Employee No. Gender F M Transgender Other Specific 2 MY DONATION‘S DIRECTION You may select more than one option. TOMORROW FUND United Way of Calgary and Area partners Calgary Please consider a Planned with the City of Chestermere, and towns of Chestermere Partnership Gift as part of your long-term Cochrane, High River, Okotoks and Strathmore. tax, financial, and estate These relationships are referred to as Area Cochrane Partnership planning strategies. Community Partnerships. To ensure your High River Partnership I have already made donation is allocated correctly, please place provisions in my estate Okotoks Partnership your designated amount in the respective box. plans or Will to support Strathmore Partnership United Way. Please contact me about United Way gift and estate Tomorrow Fund - United Way’s legacy fund planning opportunities. I want to support another registered Canadian charity and I understand this charity is not evaluated † by United Way. A $12 processing fee is subtracted for each designation to cover the cost associated with your designation. For information on Canadian charities, visit: canada.ca/en/revenue-agency/services/charities-giving/charities-listings.html. Specify Canadian Charity Release my name to the charity: Registered Charity Number** YES †Evaluation includes due diligence around financial stability and governance. **In order for us to process your designation, you must provide us with a registered charity number. -

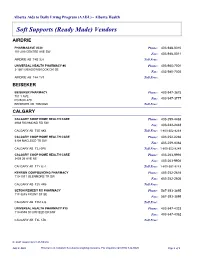

Soft Supports (Ready Made) Vendors

Alberta Aids to Daily Living Program (AADL) - Alberta Health Soft Supports (Ready Made) Vendors AIRDRIE PHARMASAVE #338 Phone: 403-948-0010 101-209 CENTRE AVE SW Fax: 403-948-0011 AIRDRIE AB T4B 3L8 Toll Free: UNIVERSAL HEALTH PHARMACY #6 Phone: 403-980-7001 3-1861 MEADOWBROOK DR SE Fax: 403-980-7002 AIRDRIE AB T4A 1V3 Toll Free: BEISEKER BEISEKER PHARMACY Phone: 403-947-3875 701 1 AVE Fax: 403-947-3777 PO BOX 470 BEISEKER AB T0M 0G0 Toll Free: CALGARY CALGARY COOP HOME HEALTH CARE Phone: 403-299-4488 4938 RICHMOND RD SW Fax: 403-242-2448 CALGARY AB T3E 6K4 Toll Free: 1-800-352-8249 CALGARY COOP HOME HEALTH CARE Phone: 403-252-2266 9309 MACLEOD TR SW Fax: 403-259-8384 CALGARY AB T2J 0P6 Toll Free: 1-800-352-8249 CALGARY COOP HOME HEALTH CARE Phone: 403-263-9994 3439 26 AVE NE Fax: 403-263-9904 CALGARY AB T1Y 6L4 Toll Free: 1-800-352-8249 KENRON COMPOUNDING PHARMACY Phone: 403-252-2616 110-1011 GLENMORE TR SW Fax: 403-252-2605 CALGARY AB T2V 4R6 Toll Free: SETON REMEDY RX PHARMACY Phone: 587-393-3895 117-3815 FRONT ST SE Fax: 587-393-3899 CALGARY AB T3M 2J6 Toll Free: UNIVERSAL HEALTH PHARMACY #10 Phone: 403-547-4323 113-8555 SCURFIELD DR NW Fax: 403-547-4362 CALGARY AB T3L 1Z6 Toll Free: © 2021 Government of Alberta July 9, 2021 This list is in constant flux due to ongoing revisions. For inquiries call (780) 422-5525 Page 1 of 6 Alberta Aids to Daily Living Program (AADL) - Alberta Health Soft Supports (Ready Made) Vendors CALGARY WELLWISE BY SHOPPERS DRUG MART Phone: 403-255-2288 25A-180 94 AVE SE Fax: 403-640-1255 CALGARY AB T2J 3G8 -

Municipal District of Bonnyville MD Campground Proposed Sanitary Dumping Station MD of BONNYVILLE, ALBERTA

Municipal District of Bonnyville MD Campground Proposed Sanitary Dumping Station MD OF BONNYVILLE, ALBERTA CONTRACT DOCUMENTS Municipal District of Bonnyville No. 87 SE DESIGN AND CONSULTING INC. INVITATION TO TENDER MUNICIPAL DISTRICT (MD) OF BONNYVILLE NO. 87 MD CAMPGROUND PROPOSED SANITARY DUMPING STATION Sealed tenders marked "Municipal District of Bonnyville No. 87, MD Campground Proposed Sanitary Dumping Station”, will be received at offices of the Municipal District of Bonnyville Parks and Recreation up to 10:00 A.M., 30 August 2019. The work generally involves the following: 1. Topsoil Stripping to 150mm 1,650 m2 2. Reclaim topsoil 100mm from stockpile and hydroseed 1,120 m2 3. Supply and Install 1200mm cast in place sanitary manhole 1 ea 4. Supply and Install Septic Tank 1 ea 5. Trenching & Backfilling for sanitary 77 l.m. 6. Trenching & Backfilling for water line 20 l.m. 7. Supply and Install 200mm sanitary sewer 77 l.m. 8. Supply and Install 450mm of 20mm granular base 50 m2 9. Supply and Place 90 mm Depth Hot Mix Asphalt (two lifts) 50 m2 10. Supply and Install 20mm Q-line water line 185 l.m. 11. Directional drill 20mm water line 165 l.m. 12. Supply and Place and compact borrow material 360 m3 13. Supply and Place concrete dumping pad 1 l.s. 14. Supply and Install water tower 1 ea. 15. Supply and Place 5’ height pressure treated fence 12 l.m. 16. Supply and Install solar powered high-level alarm 1 ea 17. Cement stabilized subgrade preparation 20Kg 520 m2 18. Supply and Place 250mm of 20mm crushed granular 520 m2 19. -

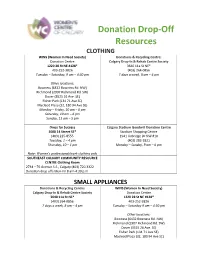

Donation Drop-Off Resources

Donation Drop-Off Resources CLOTHING WINS (Women In Need Society) Donations & Recycling Centre: Donation Centre Calgary Drop-In & Rehab Centre Society 1220 28 St NE #128* 3640 11a St NE* 403-252-3826 (403) 264-0856 Tuesday – Saturday, 9 am – 4:30 pm 7 days a week, 8 am – 4 pm Other locations: Bowness (6432 Bowness Rd. NW) Richmond (2907 Richmond Rd. SW) Dover (3525 26 Ave. SE) Fisher Park (134 71 Ave SE) Macleod Plaza (32, 180 94 Ave SE) Monday – Friday, 10 am – 6 pm Saturday, 10 am – 6 pm Sunday, 11 am – 5 pm Dress for Success Calgary Stadium Goodwill Donation Centre 1008 14 Street SE* Stadium Shopping Centre (403) 225-8555 1941 Uxbridge Dr NW #10 Tuesday, 1 – 4 pm (403) 282-2821 Thursday, 10 – 1 pm Monday – Sunday, 9 am – 6 pm Note: Women’s professional/work clothing only SOUTHEAST CALGARY COMMUNITY RESOURCE CENTRE Clothing Room 2734 – 76 Avenue S.E., Calgary (403) 720-3322 Donation drop offs Mon-Fri 8 am-4:30 p.m SMALL APPLIANCES Donations & Recycling Centre: WINS (Women In Need Society) Calgary Drop-In & Rehab Centre Society Donation Centre 3640 11a St NE* 1220 28 St NE #128* (403) 264-0856 403-252-3826 7 days a week, 8 am – 4 pm Tuesday – Saturday 9 am – 4:30 pm Other locations: Bowness (6432 Bowness Rd. NW) Richmond (2907 Richmond Rd. SW) Dover (3525 26 Ave. SE) Fisher Park (134 71 Ave SE) Macleod Plaza (32, 180 94 Ave SE) Monday - Friday, 10 am – 6 pm; Saturday, 11 am – 6 pm; Sunday 11 am – 5 pm *Locations marked with an asterisk (*) are a 10-minute drive away or less. -

2001-05482 Court Court of Queen's Bench of Alberta

COURT FILE NO.: 2001-05482 COURT COURT OF QUEEN'S BENCH OF ALBERTA JUDICIAL CENTRE CALGARY PROCEEDINGS IN THE MATTER OF THE COMPANIES’ CREDITORS ARRANGEMENT ACT, RSC 1985, c C-36, as amended AND IN THE MATTER OF THE COMPROMISE OR ARRANGEMENT OF JMB CRUSHING SYSTEMS INC. and 2161889 ALBERTA LTD. APPLICANTS JMB CRUSHING SYSTEMS INC. and 2161889 ALBERTA LTD. Gowling WLG (Canada) LLP GOWLING WLG 1600, 421 – 7th Avenue SW (CANADA) LLP Calgary, AB T2P 4K9 MATTER NO. Attn: Tom Cumming/Caireen E. Hanert/Stephen Kroeger Phone: 403-298-1938 / 403-298-1992 /403-298-1018 Fax: 403-263-9193 File No.:A163514 DOCUMENT: SERVICE LIST PARTY RELATIONSHIP Gowling WLG (Canada) LLP Counsel for Applicants, JMB 1600, 421 7th Avenue SW Crushing Systems Inc. and 2161889 Calgary AB T2P 4K9 Alberta Ltd. Attention: Tom Cumming Phone: 403-298-1938 E-mail: [email protected] Attention: Caireen E. Hanert Phone: 403-298-1992 E-mail: [email protected] Attention: Stephen Kroeger Phone: 403-298-1018 E-mail: [email protected] ACTIVE_CA\ 44753500\1 - 2 - PARTY RELATIONSHIP McCarthy Tetrault LLP Counsel for the Monitor Suite 4000, 421 7th Ave SW Calgary, AB T2P 4K9 Attention: Sean F. Collins Phone: 403-260-3531 E-mail: [email protected] Attention: Pantelis Kyriakakis Phone: 403-260-3536 Email: [email protected] FTI Consulting Canada Monitor Suite 1610, 520 – 5th Avenue SW Calgary, AB T2P 3R7 Attention: Deryck Helkaa Phone: 403-454-6031 E-mail: [email protected] Attention: Tom Powell Phone: 1-604-551-9881 E-mail: [email protected] Attention: Mike Clark Phone: 1-604-484-9537 E-mail: [email protected] Attention: Brandi Swift Phone: 1-403-454-6038 E-mail: [email protected] Miller Thomson LLP Counsel for Fiera Private Debt Fund Suite 5800, 40 King Street West VI LP, by its General Partner Toronto, ON M5H 3S1 Integrated Private Debt Fund GP Inc. -

TOWN of CHESTERMERE AGENDA for the Regular Meeting of Council to Be Held Tuesday, April 2, 2013 at 1:00Pm in Council Chambers at the Municipal Office CALL to ORDER

TOWN OF CHESTERMERE AGENDA For the Regular Meeting of Council to be held Tuesday, April 2, 2013 at 1:00pm in Council Chambers at the Municipal Office CALL TO ORDER A. ADOPTION OF AGENDA B. APPOINTMENTS C. ADOPTION OF MINUTES 2-12 1. Regular Council Meeting March 18, 2013 13 2. Special Meeting Minutes March 12, 2013 14 D. BUSINESS ARISING OUT OF THE MINUTES E. ACTIONS/DECISIONS 15 1. Cheque Listing 16-19 2. Funding Source – Unmetered Water Consumption Billing 20-23 3. Street Light Funds Allocation 24-26 4. Chestermere Recreation Center Funding Request 27-28 5. Council Remuneration Committee Recommendations 29-42 6. Energy Opportunity – Energy Associates International 43 7. Fire Apparatus F. BYLAWS 44-46 1. Bylaw 008-13, Borrowing Bylaw - Second & Third Reading 47-54 2. Bylaw 009-13, Local Improvement Project Tax Bylaw 55-57 3. Bylaw 010-13, Supplementary Assessment Bylaw G. CORRESPONDENCE & INFORMATION / MINUTES TO BE ACKNOWLEDGED 58-59 1. Council Calendar 60-62 2. AB Municipal Affairs – CRP Terms of Reference 63 3. WCB April 28th Day National Day of Mourning 64-67 4. APEGA’s Annual General Conference 68 5. YYC – 2013 AGM, Thursday, April 18th 69 6. High River – CRP Staffing Levels and Compensation 70 7. Impact of your community during Earth Hour 2013 - Chestermere e 8. CF Wild Rose Regular Meeting Minutes March 7, 2013 e 9. AUMA/AMSC March 13, 2013 & March 20, 2013 H. REPORTS 71-72 1. CAO Report I. QUESTION PERIOD J. IN CAMERA 1. Legal - Contract Negotiations K. NEW BUSINESS L. READING FILE M. -

Town of Claresholm Province of Alberta Regular Council Meeting November 25, 2019 Agenda

TOWN OF CLARESHOLM PROVINCE OF ALBERTA REGULAR COUNCIL MEETING NOVEMBER 25, 2019 AGENDA Time: 7:00 P.M. Place: Council Chambers Town of Claresholm Administration Office 221 – 45 Avenue West NOTICE OF RECORDING CALL TO ORDER AGENDA: ADOPTION OF AGENDA MINUTES: REGULAR MEETING – NOVEMBER 12, 2019 DELEGATIONS: 1. FRIENDS OF THE CLARESHOLM & DISTRICT MUSEUM RE: Cheque Presentation 2. CLARESHOLM FOOD BANK RE: Space at the Town Shop ACTION ITEMS: 1. BYLAW #1678 – Cemetery Bylaw Amendment RE: 1st Reading 2. BYLAW #1688 – Dog Bylaw Amendment RE: 1st Reading 3. CORRES: Town of Fort Macleod RE: Invitation to Santa Claus Parade – November 30, 2019 4. CORRES: The Bridges at Claresholm Golf Club RE: Bridge by Holes 6 & 7 5. CORRES: Carl Hopf RE: Resignation from the Claresholm & District Museum Board 6. REQUEST FOR DECISION: Chinook Arch Regional Library System Representative 7. REQUEST FOR DECISION: CPO Review & Policies 8. REQUEST FOR DECISION: CFEP Grant Application – Tennis Courts 9. REQUEST FOR DECISION: CARES Grant Application – Land Study 10. REQUEST FOR DIRECTION: 2020 Council Open Houses 11. INFORMATION BRIEF: Kinsmen CFEP Grant Applications 12. INFORMATION BRIEF: Council Resolution Status 13. ADOPTION OF INFORMATION ITEMS 14. IN CAMERA: a. Intergovernmental Relations – FOIP Section 21 b. Land – FOIP Section 16.1 INFORMATION ITEMS: 1. Municipal Planning Commission Minutes – October 4, 2019 2. Alberta SouthWest Bulletin – November 2019 3. Alberta SouthWest Regional Alliance Board Meeting Minutes – October 2, 2019 4. News Release – Peaks to -

To See the Printable PDF

Chestermere Seniors’ Resource Handbook EMERGENCY SERVICES IN CASE OF EMERGENCY, CALL 911 Ambulance • Fire • Police Hearing Impaired Emergencies • Ambulance ........................................................ 403-268-3673 • Fire .................................................................... 403-233-2210 • Police ................................................................ 403-265-7392 Chestermere Emergency Management Agency 403-207-7050 CHEMA coordinates disaster assistance and relief efforts in the event of a city-wide emergency. Chestermere Utilities Emergency Numbers • Gas - ATCO 24/7 ............................................. 1-800-511-3447 If you smell natural gas or have no heat in your home. • Electricity - FortisAlberta 24/7 .......................... 403-310-9473 Check the outage map on the website first. • Water/sewer - EPCOR Trouble line ................ 1-888-775-6677 Poison Centre (Alberta Health Services) 1-800-332-1414 * * * * * * Centre for Suicide Prevention 24/7 help line: 1-833-456-4566 (Calgary) or text 4564 (2-10 p.m.) Distress Centre 24/7 Crisis Line: 403-266-4357 (Calgary) distresscentre.com [email protected] Kerby Elder Abuse (To report or get info) 403-705-3250 (Calgary) Mental Health Help Line 24/7 help line: 1-877-303-2642 (Alberta Health Services) Table of Contents EMERGENCY SERVICES ......................................Pull-out sheet CITY OF CHESTERMERE - HANDY NUMBERS ......................... 1 ADVOCACY & SUPPORT GROUPS ......................................... 3 ARTS, CULTURE & ENTERTAINMENT -

Pincher Creek, Alberta Introduction

Assessment Findings & Suggestions June 2007 Pincher Creek, Alberta INTRODUCTION First impressions and some ideas to increase tourism spending In June of 2007, a Community Tourism Assessment of Pincher Creek, Alberta was conducted, and the findings were presented in a two-hour workshop. The assessment provides an unbiased overview of the community – how it is seen by a visitor. It includes a review of local marketing efforts, signs, at- tractions, critical mass, retail mix, ease of getting around, customer service, visitor amenities such as parking and public wash rooms, overall appeal, and the community’s ability to attract overnight visitors. In performing the “Community Assessment,” we looked at the area through the eyes of a first-time visitor. No prior research was facilitated, and no com- munity representatives were contacted except to set up the project, and the town and surrounding area were “secretly shopped.” There are two primary elements to the assessment process: First is the “Mar- keting Effectiveness Assessment.” How easy is it for potential visitors to find information about the commu- nity or area? Once they find information, are your marketing materials good enough to close the sale? In the Marketing Effectiveness Assessment, we as- signed two (or more) people to plan trips into the general region. They did not know, in advance, who the assessment was for. They used whatever re- sources they would typically use in planning a trip: travel guides, brochures, the internet, calling visitor information centers, review of marketing materials, etc. - just as you might do in planning a trip to a “new” area or destination. -

Monitor's Fifth Report

COURT FILE 2001 06423 Clerk's NUMBER Stamp COURT COURT OF QUEEN’S BENCH OF ALBERTA JUDICIAL CALGARY CENTRE IN THE MATTER OF THE COMPANIES’ CREDITORS ARRANGEMENT ACT, R.S.C. 1985, c. C-36, as amended AND IN THE MATTER OF A PLAN OF COMPROMISE OR ARRANGEMENT OF ENTREC CORPORATION, CAPSTAN HAULING LTD., ENTREC ALBERTA LTD., ENT CAPITAL CORP., ENTREC CRANES & HEAVY HAUL INC., ENTREC HOLDINGS INC., ENT OILFIELD GROUP LTD. and ENTREC SERVICES LTD. DOCUMENT FIFTH REPORT OF THE MONITOR October 5, 2020 ADDRESS FOR MONITOR SERVICE AND Alvarez & Marsal Canada Inc. CONTACT 250 6th Avenue SW, Suite 1110 INFORMATION Calgary, AB T2P 3H7 OF PARTY FILING THIS Phone: +1 604.638.7440 DOCUMENT Fax: +1 604.638.7441 Email: [email protected] / [email protected] Attention: Anthony Tillman / Vicki Chan COUNSEL Norton Rose Fulbright Canada LLP 400 3rd Avenue SW, Suite 3700 Calgary, Alberta T2P 4H2 Phone: +1 403.267.8222 Fax: +1 403.264.5973 Email: [email protected] / [email protected] Attention: Howard A. Gorman, Q.C. / Gunnar Benediktsson TABLE OF CONTENTS 1.0 INTRODUCTION ...................................................................................................................... - 3 - 2.0 PURPOSE ................................................................................................................................... - 6 - 3.0 TERMS OF REFERENCE ......................................................................................................... - 7 - 4.0 ACTIVITIES OF THE -

2020 Annual Report the Year-Over-Year Increase of $75.3 Million in Long-Term Debt the Operating Facility of $33.3 Million (2019 – $12.3 Million)

CMLC ANNUAL REPORT 2020 2 3 CONTENTS 04 INTRODUCTION 42 STRATEGIC PLAN UPDATE 08 HIGHLIGHTS & MILESTONES 47 INDEPENDENT AUDITOR’S OF 2020 REPORT 10 City-building highlights 50 ACCOUNTABILITY & 15 Planning & infrastructure GOVERNANCE 19 Land sales & 57 MANAGEMENT’S DISCUSSION commercial leasing & ANALYSIS 22 Development partner activity 61 REPORT OF MANAGEMENT 26 Retail openings 62 FINANCIAL STATEMENTS 30 Project management 68 NOTES TO FINANCIAL 34 Programming & public art STATEMENTS 38 Marketing 84 TEAM CMLC 40 Corporate communications 41 Safety & vitality 4 5 “In a truly extraordinary year, CMLC rose above countless challenges and delivered, INTRODUCTION as always, exceptional projects for our city and outstanding value for our shareholder. Despite the limitations everyone faced in a year defined by COVID-19, where our daily routines and typical ways of working were completely upended, CMLC found ways to roll with the punches and forge stalwartly onward with our important community- building work.” KATE THOMPSON President & CEO 7 RISING TO NEW CHALLENGES For nearly everyone on the planet, 2020 was a year dramatically defined by the challenges and the changes wrought by the COVID-19 crisis. As its ripple effects reverberated through our community, our resilience as an organization was put swiftly and continually to the test. And, as we’ve always done in the face of unforeseen obstacles, after calmly and thoughtfully taking stock of our projects and the risks we now had to consider, CMLC rose confidently to these new challenges. This new world order called for extraordinary adaptations in every facet of our business—our ongoing redevelopment and construction activities, the many ways we support our partners, and the placemaking and community programming initiatives that have underpinned our success here in Calgary’s east end from the outset. -

Meet Calgary Air Travel

MEET CALGARY AIR TRAVEL London (Heathrow) Amsterdam London (Gatwick) Frankfurt Seattle Portland Minneapolis Salt Lake City New York (JFK) Chicago Newark Denver San Francisco Las Vegas Palm Springs Los Angeles Dallas/Ft.Worth San Diego Phoenix Houston Orlando London (Heathrow) Amsterdam San Jose del Cabo Varadero Puerto Vallarta Cancun London (Gatwick) Mexico City Frankfurt Montego Bay Seattle Portland Minneapolis Salt Lake City New York (JFK) Chicago Newark Denver San Francisco Las Vegas Palm Springs Los Angeles Dallas/Ft.Worth San Diego Phoenix Houston Orlando San Jose del Cabo Varadero Puerto Vallarta Cancun Mexico City Montego Bay Time Zone Passport Requirements Calgary, Alberta is on MST Visitors to Canada require a valid passport. (Mountain Standard Time) For information on visa requirements visit Canada Border Services Agency: cbsa-asfc.gc.ca CALGARY AT A GLANCE HOTEL & VENUES Calgary is home to world-class accommodations, with over 13,000 guest rooms, there’s Alberta is the only province in +15 Calgary’s +15 Skywalk system Canada without a provincial sales Skywalk is the world’s largest indoor, something for every budget and preference. Meetings + Conventions Calgary partners with tax (PST). The Government of pedestrian pathway network. The Calgary’s hotels and venues to provide event planners with direct access to suppliers without the added step of connecting with each facility individually. Canada charges five per cent goods weather-protected walkways are and services tax (GST) on most about 15 feet above the ground purchases. level and run for a total of 11 miles. Calgary TELUS The +15 links Calgary’s downtown Convention Centre Bring your shades.