Durham E-Theses

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

First Evidence of Farming Appears; Stone Axes, Antler Combs, Pottery in Common Use

BC c.5000 - Neolithic (new stone age) Period begins; first evidence of farming appears; stone axes, antler combs, pottery in common use. c.4000 - Construction of the "Sweet Track" (named for its discoverer, Ray Sweet) begun; many similar raised, wooden walkways were constructed at this time providing a way to traverse the low, boggy, swampy areas in the Somerset Levels, near Glastonbury; earliest-known camps or communities appear (ie. Hembury, Devon). c.3500-3000 - First appearance of long barrows and chambered tombs; at Hambledon Hill (Dorset), the primitive burial rite known as "corpse exposure" was practiced, wherein bodies were left in the open air to decompose or be consumed by animals and birds. c.3000-2500 - Castlerigg Stone Circle (Cumbria), one of Britain's earliest and most beautiful, begun; Pentre Ifan (Dyfed), a classic example of a chambered tomb, constructed; Bryn Celli Ddu (Anglesey), known as the "mound in the dark grove," begun, one of the finest examples of a "passage grave." c.2500 - Bronze Age begins; multi-chambered tombs in use (ie. West Kennet Long Barrow) first appearance of henge "monuments;" construction begun on Silbury Hill, Europe's largest prehistoric, man-made hill (132 ft); "Beaker Folk," identified by the pottery beakers (along with other objects) found in their single burial sites. c.2500-1500 - Most stone circles in British Isles erected during this period; pupose of the circles is uncertain, although most experts speculate that they had either astronomical or ritual uses. c.2300 - Construction begun on Britain's largest stone circle at Avebury. c.2000 - Metal objects are widely manufactured in England about this time, first from copper, then with arsenic and tin added; woven cloth appears in Britain, evidenced by findings of pins and cloth fasteners in graves; construction begun on Stonehenge's inner ring of bluestones. -

Bibliography19802017v2.Pdf

A LIST OF PUBLICATIONS ON THE HISTORY OF WARWICKSHIRE, PUBLISHED 1980–2017 An amalgamation of annual bibliographies compiled by R.J. Chamberlaine-Brothers and published in Warwickshire History since 1980, with additions from readers. Please send details of any corrections or omissions to [email protected] The earlier material in this list was compiled from the holdings of the Warwickshire County Record Office (WCRO). Warwickshire Library and Information Service (WLIS) have supplied us with information about additions to their Local Studies material from 2013. We are very grateful to WLIS for their help, especially Ms. L. Essex and her colleagues. Please visit the WLIS local studies web pages for more detailed information about the variety of sources held: www.warwickshire.gov.uk/localstudies A separate page at the end of this list gives the history of the Library collection, parts of which are over 100 years old. Copies of most of these published works are available at WCRO or through the WLIS. The Shakespeare Birthplace Trust also holds a substantial local history library searchable at http://collections.shakespeare.org.uk/. The unpublished typescripts listed below are available at WCRO. A ABBOTT, Dorothea: Librarian in the Land Army. Privately published by the author, 1984. 70pp. Illus. ABBOTT, John: Exploring Stratford-upon-Avon: Historical Strolls Around the Town. Sigma Leisure, 1997. ACKROYD, Michael J.M.: A Guide and History of the Church of Saint Editha, Amington. Privately published by the author, 2007. 91pp. Illus. ADAMS, A.F.: see RYLATT, M., and A.F. Adams: A Harvest of History. The Life and Work of J.B. -

How Useful Are Episcopal Ordination Lists As a Source for Medieval English Monastic History?

Jnl of Ecclesiastical History, Vol. , No. , July . © Cambridge University Press doi:./S How Useful are Episcopal Ordination Lists as a Source for Medieval English Monastic History? by DAVID E. THORNTON Bilkent University, Ankara E-mail: [email protected] This article evaluates ordination lists preserved in bishops’ registers from late medieval England as evidence for the monastic orders, with special reference to religious houses in the diocese of Worcester, from to . By comparing almost , ordination records collected from registers from Worcester and neighbouring dioceses with ‘conven- tual’ lists, it is concluded that over per cent of monks and canons are not named in the extant ordination lists. Over half of these omissions are arguably due to structural gaps in the surviving ordination lists, but other, non-structural factors may also have contributed. ith the dispersal and destruction of the archives of religious houses following their dissolution in the late s, many docu- W ments that would otherwise facilitate the prosopographical study of the monastic orders in late medieval England and Wales have been irre- trievably lost. Surviving sources such as the profession and obituary lists from Christ Church Canterbury and the records of admissions in the BL = British Library, London; Bodl. Lib. = Bodleian Library, Oxford; BRUO = A. B. Emden, A biographical register of the University of Oxford to A.D. , Oxford –; CAP = Collectanea Anglo-Premonstratensia, London ; DKR = Annual report of the Deputy Keeper of the Public Records, London –; FOR = Faculty Office Register, –, ed. D. S. Chambers, Oxford ; GCL = Gloucester Cathedral Library; LP = J. S. Brewer and others, Letters and papers, foreign and domestic, of the reign of Henry VIII, London –; LPL = Lambeth Palace Library, London; MA = W. -

Final Thesis.Pdf

Canterbury Christ Church University’s repository of research outputs http://create.canterbury.ac.uk Copyright © and Moral Rights for this thesis are retained by the author and/or other copyright owners. A copy can be downloaded for personal non-commercial research or study, without prior permission or charge. This thesis cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the copyright holder/s. The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holders. When referring to this work, full bibliographic details including the author, title, awarding institution and date of the thesis must be given e.g. Kersey, H. (2017) Aristocratic female inheritance and property holding in thirteenth-century England. Ph.D. thesis, Canterbury Christ Church University. Contact: [email protected] ARISTOCRATIC FEMALE INHERITANCE AND PROPERTY HOLDING IN THIRTEENTH-CENTURY ENGLAND By Harriet Lily Kersey Canterbury Christ Church University Thesis submitted for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy 2017 ii Abstract This thesis explores aristocratic female inheritance and property holding in the thirteenth century, a relatively neglected topic within existing scholarship. Using the heiresses of the earldoms and honours of Chester, Pembroke, Leicester and Winchester as case studies, this thesis sheds light on the processes of female inheritance and the effects of coparceny in a turbulent period of English history. The lives of the heiresses featured in this thesis span the reigns of three English kings: John, Henry III and Edward I. The reigns of John and Henry saw bitter civil wars, whilst Edward’s was plagued with expensive foreign wars. -

Durham Liber Vitae

-414- DURHAM LIBER VITAE Durham Liber Vitae: First page (as shown on the project website) with the name of King Athelstan, supposed donor of the liber to Durham, at the top. Reproduced by permission of British Library. Further copying prohibited. © British Library: Cotton Domitian A. VII f.15r DURHAM LIBER VITAE -415- THE DURHAM LIBER VITAE: SOME REFLECTIONS ON ITS SIGNIFICANCE AS A GENEALOGICAL RESOURCE by Rosie Bevan1 ABSTRACT The Durham Liber Vitae holds great potential for the extraction of unmined genealogical information held within its pages, but the quality of information obtained will depend on our understanding of the document itself. This article explores briefly what a liber vitae was and gives examples of the type of information that can be extracted from the Durham liber with special reference to Countess Ida, mother of William Longespee. Foundations (2005) 1 (6): 414-424 © Copyright FMG The Durham Liber Vitae (Book of Life), which contains over 11,000 medieval names on 83 folios, recorded over a period from the ninth to the sixteenth century, is receiving some well-deserved study2. The names in the Liber Vitae are of benefactors to St Cuthbert’s, Durham, and included kings and earls, as well as other landowning laity. Also appearing in large numbers are the names of those belonging to the religious community itself over that period. From the late 1000s Breton and Norman- French names feature, intermingling with those belonging to Anglo-Saxon, Scottish and Scandinavian families, witness to intermarriage between, and eventual cultural dominance over, racial groups and land in northern England. -

Diocesan Synod Digest

DIOCESAN SYNOD ACTS 16 March 2017 Acts of the Diocesan Synod held on 16 March 2017 at St Luke’s Hedge End. 70 members were in attendance. The Revd Fiona Gibbs and Mr Nigel Williams led members in opening worship. The Bishop of Winchester welcomed members. AMAP PROPOSALS 2017-1019, DS 17/01 Vision & Implementation of Strategic Priorities The Bishop of Winchester shared an overview of the vision and implementation of the diocesan strategic priorities at a diocesan and archidiaconal level, focusing on sustainable growth for the common good, with the intention to be proactive rather than reactive. Four projects were proposed: 1. Benefice of the Future, Promote Rural Evangelism & Discipleship The Archdeacon of Winchester presented proposals for the Benefice of the Future to be trialled in three benefices initially: Pastrow with Hurstbourne Tarrant & Faccombe & Vernham Dean & Linkenholt; North Hampshire Downs; Avon Valley. 2. Invest Where There is the Greatest Potential for Numerical Growth – Resource Churches Planted, Flourishing and Preparing to Plant Again The Archdeacon of Bournemouth presented proposals for Resource Churches, with initial plans to go into Southampton and Basingstoke, each Resource Church to develop a pipeline to plant other churches. 3. Major Development Areas (MDA) – the Church Supports Sustainable Community Development and Offers a Missional Christian Presence The Bishop of Basingstoke presented an overview of areas across the diocese which will see developments of 250+ houses over the next few years; proposing that the diocese must engage with the new communities as soon as possible to ensure a Christian presence. 4. Further & Higher Education – Grow and Deepen the Church’s Engagement with Students and Institutions The Bishop of Winchester presented members with an overview of Further and Higher Education and the challenges the church faces with engagement. -

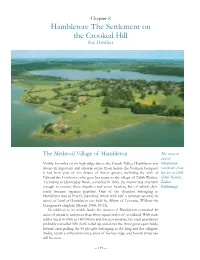

Hambleton 5/10/07 17:42 Page 1

Hambleton 5/10/07 17:42 Page 1 Chapter 8 Hambleton: The Settlement on the Crooked Hill Sue Howlett The Medieval Village of Hambleton The western end of Visible for miles on its high ridge above the Gwash Valley, Hambleton was Hambleton always an important and valuable estate. Even before the Norman Conquest peninsula from it had been part of the dower of Saxon queens, including the wife of the air in 2006 Edward the Confessor, who gave her name to the village of Edith Weston. (John Nowell, According to Domesday Book, compiled in 1086, the manor was extensive Zodiac enough to contain three churches and seven hamlets, five of which after- Publishing) wards became separate parishes. One of the churches belonging to Hambleton was St Peter’s, Stamford, which with half a carucate (around 60 acres) of land at Hambleton was held by Albert of Lorraine, William the Conquerer’s chaplain (Morris 1980, 19-21). In addition to its arable lands, the manor of Hambleton contained 40 acres of meadow and more than three square miles of woodland. With male adults listed in 1086 as 140 villeins and thirteen bordars, the total population probably exceeded 500. Serfs toiled up and down the three great open fields, behind oxen pulling the 45 ploughs belonging to the king and the villagers. Today, nearly a millennium later, areas of former ridge and furrow strips can still be seen. – 149 – Hambleton 5/10/07 17:43 Page 2 An 1839 drawing of Hambleton Church (Uppingham School Archives) Some time after the Domesday survey, William the Conquerer granted Hambleton to the powerful Norman family of Umfraville, who sub-divided the large and sprawling manor into two: Great and Little Hambleton. -

Index to Engravings in the Proceedings of the Society Of

/ r / INDEX SOCIETY. E> OCCASIONAL INDEXES. I. INDEX TO ENGRAVINGS IN THE I PROCEEDINGS OF THE SOCIETY OF ANTIQUARIES. BY EDWARD PEACOCK, F.S.A. V -Λ\’ LONDON: PUBLISHED FOR THE INDEX SOCIETY BY FARRAR & FENTON, 8, JOHN STREET, ADELPHI, W.C. ■·.··* ' i: - ··. \ MDCCCLXXXV. ' Price Half a Crown. 2730130227001326270013022700440227004426 INDEX SOCIETY. T he Council greatly regret that owing to various circum stances the publications have fallen very much behindhand in the order of their publication, but they trust that in the future the Members will have no reason to complain on this score. The Index of Obituary Notices for 1882 is ready and will be in the Members’ hands immediately. The Index for 1883 is nearly ready, and this with the Index to Archaeological Journals and Transactions, upon which Mr. Gomme has been engaged for some time, will complete the publications for 1884. The Index of the Biographical and Obituary Notices in the Gentleman’s Magazine for the first fifty years, upon which Mr. Farrar is engaged, has occupied an amount of time in revision considerably greater than was expected. This is largely owing to the great differences in the various sets, no two being alike. No one who has not been in the habit of consulting the early volumes of this Magazine con stantly can have any idea of the careless manner in which it was printed and the vast amount of irregularity in the pagination. Mr. Farrar has spared no pains in the revision of these points and the Council confidently expect to be able to present Members with the first volume of this im portant work in the course of the present year (1885). -

Pedigree of the Wilson Family N O P

Pedigree of the Wilson Family N O P Namur** . NOP-1 Pegonitissa . NOP-203 Namur** . NOP-6 Pelaez** . NOP-205 Nantes** . NOP-10 Pembridge . NOP-208 Naples** . NOP-13 Peninton . NOP-210 Naples*** . NOP-16 Penthievre**. NOP-212 Narbonne** . NOP-27 Peplesham . NOP-217 Navarre*** . NOP-30 Perche** . NOP-220 Navarre*** . NOP-40 Percy** . NOP-224 Neuchatel** . NOP-51 Percy** . NOP-236 Neufmarche** . NOP-55 Periton . NOP-244 Nevers**. NOP-66 Pershale . NOP-246 Nevil . NOP-68 Pettendorf* . NOP-248 Neville** . NOP-70 Peverel . NOP-251 Neville** . NOP-78 Peverel . NOP-253 Noel* . NOP-84 Peverel . NOP-255 Nordmark . NOP-89 Pichard . NOP-257 Normandy** . NOP-92 Picot . NOP-259 Northeim**. NOP-96 Picquigny . NOP-261 Northumberland/Northumbria** . NOP-100 Pierrepont . NOP-263 Norton . NOP-103 Pigot . NOP-266 Norwood** . NOP-105 Plaiz . NOP-268 Nottingham . NOP-112 Plantagenet*** . NOP-270 Noyers** . NOP-114 Plantagenet** . NOP-288 Nullenburg . NOP-117 Plessis . NOP-295 Nunwicke . NOP-119 Poland*** . NOP-297 Olafsdotter*** . NOP-121 Pole*** . NOP-356 Olofsdottir*** . NOP-142 Pollington . NOP-360 O’Neill*** . NOP-148 Polotsk** . NOP-363 Orleans*** . NOP-153 Ponthieu . NOP-366 Orreby . NOP-157 Porhoet** . NOP-368 Osborn . NOP-160 Port . NOP-372 Ostmark** . NOP-163 Port* . NOP-374 O’Toole*** . NOP-166 Portugal*** . NOP-376 Ovequiz . NOP-173 Poynings . NOP-387 Oviedo* . NOP-175 Prendergast** . NOP-390 Oxton . NOP-178 Prescott . NOP-394 Pamplona . NOP-180 Preuilly . NOP-396 Pantolph . NOP-183 Provence*** . NOP-398 Paris*** . NOP-185 Provence** . NOP-400 Paris** . NOP-187 Provence** . NOP-406 Pateshull . NOP-189 Purefoy/Purifoy . NOP-410 Paunton . NOP-191 Pusterthal . -

University of Southampton Research Repository Eprints Soton

University of Southampton Research Repository ePrints Soton Copyright © and Moral Rights for this thesis are retained by the author and/or other copyright owners. A copy can be downloaded for personal non-commercial research or study, without prior permission or charge. This thesis cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the copyright holder/s. The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holders. When referring to this work, full bibliographic details including the author, title, awarding institution and date of the thesis must be given e.g. AUTHOR (year of submission) "Full thesis title", University of Southampton, name of the University School or Department, PhD Thesis, pagination http://eprints.soton.ac.uk i UNIVERSITY OF SOUTHAMPTON FACULTY OF HUMANITIES School of History The Wydeviles 1066-1503 A Re-assessment by Lynda J. Pidgeon Thesis for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy 15 December 2011 ii iii ABSTRACT Who were the Wydeviles? The family arrived with the Conqueror in 1066. As followers in the Conqueror’s army the Wydeviles rose through service with the Mowbray family. If we accept the definition given by Crouch and Turner for a brief period of time the Wydeviles qualified as barons in the twelfth century. This position was not maintained. By the thirteenth century the family had split into two distinct branches. The senior line settled in Yorkshire while the junior branch settled in Northamptonshire. The junior branch of the family gradually rose to prominence in the county through service as escheator, sheriff and knight of the shire. -

Of St Cuthbert'

A Literary Pilgrimage of Durham by Ruth Robson of St Cuthbert' 1. Market Place Welcome to A Literary Pilgrimage of Durham, part of Durham Book Festival, produced by New Writing North, the regional writing development agency for the North of England. Durham Book Festival was established in the 1980s and is one of the country’s first literary festivals. The County and City of Durham have been much written about, being the birthplace, residence, and inspiration for many writers of both fact, fiction, and poetry. Before we delve into stories of scribes, poets, academia, prize-winning authors, political discourse, and folklore passed down through generations, we need to know why the city is here. Durham is a place steeped in history, with evidence of a pre-Roman settlement on the edge of the city at Maiden Castle. Its origins as we know it today start with the arrival of the community of St Cuthbert in the year 995 and the building of the white church at the top of the hill in the centre of the city. This Anglo-Saxon structure was a precursor to today’s cathedral, built by the Normans after the 1066 invasion. It houses both the shrine of St Cuthbert and the tomb of the Venerable Bede, and forms the Durham UNESCO World Heritage Site along with Durham Castle and other buildings, and their setting. The early civic history of Durham is tied to the role of its Bishops, known as the Prince Bishops. The Bishopric of Durham held unique powers in England, as this quote from the steward of Anthony Bek, Bishop of Durham from 1284-1311, illustrates: ‘There are two kings in England, namely the Lord King of England, wearing a crown in sign of his regality and the Lord Bishop of Durham wearing a mitre in place of a crown, in sign of his regality in the diocese of Durham.’ The area from the River Tees south of Durham to the River Tweed, which for the most part forms the border between England and Scotland, was semi-independent of England for centuries, ruled in part by the Bishop of Durham and in part by the Earl of Northumberland. -

The Sovereign Grant and Sovereign Grant Reserve Annual Report and Accounts 2017-18

SOVEREIGN GRANT ACT 2011 The Sovereign Grant and Sovereign Grant Reserve Annual Report and Accounts 2017-18 Presented to Parliament pursuant to Section 2 and Section 4 of the Sovereign Grant Act 2011 Ordered by the House of Commons to be printed 27 June 2018 HC 1153 © Crown copyright 2018 This publication is licensed under the terms of the Open Government Licence v3.0 except where otherwise stated. To view this licence, visit nationalarchives.gov.uk/doc/open- government-licence/version/3 Where we have identified any third party copyright information you will need to obtain permission from the copyright holders concerned. This publication is available at www.gov.uk/government/publications Any enquiries regarding this publication should be sent to us using the contact details available at www.royal.uk ISBN 978-1-5286-0459-8 CCS 0518725758 06/18 Printed on paper containing 75% recycled fibre content minimum. Printed in the UK on behalf of the Controller of Her Majesty’s Stationery Office. Produced by Impress Print Services Limited. FRONT COVER: Queen Elizabeth II and The Duke of Edinburgh visit Stirling Castle on 5th July 2017. Photograph provided courtesy of Jane Barlow/Press Association. CONTENTS Page The Sovereign Grant 2 The Official Duties of The Queen 3 Performance Report 9 Accountability Report: Governance Statement 27 Remuneration and Staff Report 40 Statement of the Keeper of the Privy Purse’s Financial Responsibilities 44 The Certificate and Report of the Comptroller and Auditor General to the Houses of 46 Parliament and the Royal