Download Full-Text

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Timeline of Key Events: March 2011: Anti-Government Protests Broke

Timeline of key events: March 2011: Anti-government protests broke out in Deraa governorate calling for political reforms, end of emergency laws and more freedoms. After government crackdown on protestors, demonstrations were nationwide demanding the ouster of Bashar Al-Assad and his government. July 2011: Dr. Nabil Elaraby, Secretary General of the League of Arab States (LAS), paid his first visit to Syria, after his assumption of duties, and demanded the regime to end violence, and release detainees. August 2011: LAS Ministerial Council requested its Secretary General to present President Assad with a 13-point Arab initiative (attached) to resolve the crisis. It included cessation of violence, release of political detainees, genuine political reforms, pluralistic presidential elections, national political dialogue with all opposition factions, and the formation of a transitional national unity government, which all needed to be implemented within a fixed time frame and a team to monitor the above. - The Free Syrian Army (FSA) was formed of army defectors, led by Col. Riad al-Asaad, and backed by Arab and western powers militarily. September 2011: In light of the 13-Point Arab Initiative, LAS Secretary General's and an Arab Ministerial group visited Damascus to meet President Assad, they were assured that a series of conciliatory measures were to be taken by the Syrian government that focused on national dialogue. October 2011: An Arab Ministerial Committee on Syria was set up, including Algeria, Egypt, Oman, Sudan and LAS Secretary General, mandated to liaise with Syrian government to halt violence and commence dialogue under the auspices of the Arab League with the Syrian opposition on the implementation of political reforms that would meet the aspirations of the people. -

Between Russia and Iran: Room to Pursue American Interests in Syria by John W

STRATEGIC PERSPECTIVES 27 Between Russia and Iran: Room to Pursue American Interests in Syria by John W. Parker Center for Strategic Research Institute for National Strategic Studies National Defense University Institute for National Strategic Studies National Defense University The Institute for National Strategic Studies (INSS) is National Defense University’s (NDU’s) dedicated research arm. INSS includes the Center for Strategic Research, Center for the Study of Chinese Military Affairs, and Center for the Study of Weapons of Mass Destruction. The military and civilian analysts and staff who comprise INSS and its subcomponents execute their mission by conducting research and analysis, publishing, and participating in conferences, policy support, and outreach. The mission of INSS is to conduct strategic studies for the Secretary of Defense, Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, and the unified combatant commands in support of the academic programs at NDU and to perform outreach to other U.S. Government agencies and the broader national security community. Cover: In the Gothic Hall of the Presidential Palace in Helsinki, Finland, President Donald Trump met with President Vladimir Putin on July 16, 2018, to start the U.S.-Russia summit. (President of Russia Web site/Kremlin.ru) Between Russia and Iran Between Russia and Iran: Room to Pursue American Interests in Syria By John W. Parker Institute for National Strategic Studies Strategic Perspectives, No. 27 Series Editor: Thomas F. Lynch III National Defense University Press Washington, D.C. January 2019 Opinions, conclusions, and recommendations expressed or implied within are solely those of the contributors and do not necessarily represent the views of the Defense Department or any other agency of the Federal Government. -

Putin's Syrian Gambit: Sharper Elbows, Bigger Footprint, Stickier Wicket

STRATEGIC PERSPECTIVES 25 Putin’s Syrian Gambit: Sharper Elbows, Bigger Footprint, Stickier Wicket by John W. Parker Center for Strategic Research Institute for National Strategic Studies National Defense University Institute for National Strategic Studies National Defense University The Institute for National Strategic Studies (INSS) is National Defense University’s (NDU’s) dedicated research arm. INSS includes the Center for Strategic Research, Center for Complex Operations, Center for the Study of Chinese Military Affairs, and Center for Technology and National Security Policy. The military and civilian analysts and staff who comprise INSS and its subcomponents execute their mission by conducting research and analysis, publishing, and participating in conferences, policy support, and outreach. The mission of INSS is to conduct strategic studies for the Secretary of Defense, Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, and the unified combatant commands in support of the academic programs at NDU and to perform outreach to other U.S. Government agencies and the broader national security community. Cover: Admiral Kuznetsov aircraft carrier, August, 2012 (Russian Ministry of Defense) Putin's Syrian Gambit Putin's Syrian Gambit: Sharper Elbows, Bigger Footprint, Stickier Wicket By John W. Parker Institute for National Strategic Studies Strategic Perspectives, No. 25 Series Editor: Denise Natali National Defense University Press Washington, D.C. July 2017 Opinions, conclusions, and recommendations expressed or implied within are solely those of the contributors and do not necessarily represent the views of the Defense Department or any other agency of the Federal Government. Cleared for public release; distribution unlimited. Portions of this work may be quoted or reprinted without permission, provided that a standard source credit line is included. -

Armed Conflict in Syria: Overview and U.S. Response

Armed Conflict in Syria: Overview and U.S. Response Carla E. Humud, Coordinator Analyst in Middle Eastern Affairs Christopher M. Blanchard Specialist in Middle Eastern Affairs Mary Beth D. Nikitin Specialist in Nonproliferation May 16, 2017 Congressional Research Service 7-5700 www.crs.gov RL33487 Armed Conflict in Syria: Overview and U.S. Response Summary A deadly chemical weapons attack in Syria on April 4, 2017, and a U.S. military strike in response on April 6 returned the Syrian civil war—now in its seventh year—to the forefront of international attention. In response to the April 4 attack, some Members of Congress called for the United States to conduct a punitive military operation. These Members and some others since have praised President Trump’s decision to launch a limited strike, although some also have called on the President to consult with Congress about Syria strategy. Other Members have questioned the President’s authority to launch the strike in the absence of specific prior authorization from Congress. In the past, some in Congress have expressed concern about the international and domestic authorizations for such strikes, their potential unintended consequences, and the possibility of undesirable or unavoidable escalation. Since taking office in January 2017, President Trump has stated his intention to “destroy” the Syria- and Iraq-based insurgent terrorist group known as the Islamic State (IS, also known as ISIL, ISIS, or the Arabic acronym Da’esh), and the President has ordered actions to “accelerate” U.S. military efforts against the group in both countries. In late March, senior U.S. -

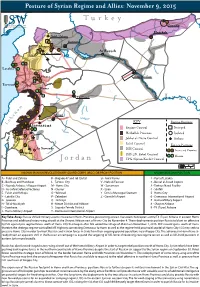

Regime and Allies: November 9, 2015

Posture of Syrian Regime and Allies: November 9, 2015 Turkey Z Qamishli Hasakah Nubl / Zahraa A Kuweires Aleppo B E C D Ar Raqqah Fu’ah / Kefraya Idlib 4 1 F G Latakia 2 H I J Hama Deir ez-Zor 3 7 K Tartous L Homs 5 M S 9 Y R I A N 8 T4 (Tiyas) Iraq n o n O a Sayqal b P e KEY Regime Positions L Q R Damascus S T 6 Regime Control Besieged U V Hezbollah Presence Isolated W Quneitra Jabhat al-Nusra Control Airbase l Rebel Control e X Foreign Positions a r As Suwayda ISIS Control s Y A B Iran and Proxies I Deraa ISIS, JN, Rebel Control 1 2 Russia Jordan YPG (Syrian Kurds) Control 10 mi 20 km KNOWN IRANIAN REVOLUTIONARY GUARD CORPS (IRGC) OR PROXY POSITION KNOWN RUSSIAN POSITION A - Nubl and Zahraa K - Brigade 47 and Tel Qartal U - Amal Farms 1 - Port of Latakia B - Bashkuy and Handarat L - Tartous City V - Nabi al-Fawwar 2 - Bassel al-Assad Airport C - Neyrab Airbase / Aleppo Airport M - Homs City W - Sanamayn 3 - Tartous Naval Facility D - As-Sara Defense Factories N - Qusayr X - Izraa 4 - Slinfah E - Fu’ah and Kefraya O - Yabroud Y - Dera’a Municipal Stadium 5 - Homs City F - Latakia City P - Zabadani Z - Qamishli Airport 6 - Damascus International Airport G - Joureen Q - Jamraya 7 - Hama Military Airport H - Tel al-Nasiriyah R - Mezze District and Airbase 8 - Shayrat Airbase I - Qumhana S - Sayyida Zeinab District 9 - T4 (Tiyas) Airbase J - Hama Military Airport T - Damascus International Airport Key Take-Away: Russia shifted military assets into eastern Homs Province, positioning at least ve attack helicopters at the T4 (Tiyas) Airbase in eastern Homs Province and additional rotary-wing aircraft at the Shayrat Airbase east of Homs City by November 4. -

Operation Inherent Resolve Report to the United States Congress, April 1, 2017-June 30, 2017

LEAD INSPECTOR GENERAL FOR OVERSEAS CONTINGENCY OPERATIONS OPERATION INHERENT RESOLVE REPORT TO THE UNITED STATES CONGRESS APRIL 1, 2017‒JUNE 30, 2017 APRIL 1, 2017‒JUNE 30, 2017 I LEAD IG REPORT TO THE U.S. CONGRESS I i LEAD INSPECTOR GENERAL MISSION The Lead Inspector General for Overseas Contingency Operations coordinates among the Inspectors General specified under the law to: • develop a joint strategic plan to conduct comprehensive oversight over all aspects of the contingency operation • ensure independent and effective oversight of all programs and operations of the federal government in support of the contingency operation through either joint or individual audits, inspections, and investigations • promote economy, efficiency, and effectiveness and prevent, detect, and deter fraud, waste, and abuse • perform analyses to ascertain the accuracy of information provided by federal agencies relating to obligations and expenditures, costs of programs and projects, accountability of funds, and the award and execution of major contracts, grants, and agreements • report quarterly and biannually to the Congress and the public on the contingency operation and activities of the Lead Inspector General (Pursuant to sections 2, 4, and 8L of the Inspector General Act of 1978) FOREWORD We are pleased to submit the Lead Inspector General (Lead IG) quarterly Operation Inherent Resolve Report to the United States Congress for the period April 1 to June 30, 2017. This is our 10th quarterly report on this overseas contingency operation (OCO), discharging our individual and collective agency oversight responsibilities pursuant to sections 2, 4, and 8L of the Inspector General Act of 1978. Operation Inherent Resolve (OIR) is dedicated to countering the terrorist threat posed by the Islamic State of Iraq and Syria (ISIS) in Iraq, Syria, the region, and the broader international community. -

Syria After the Missile Strikes: Policy Options

SYRIA AFTER THE MISSILE STRIKES: POLICY OPTIONS HEARING BEFORE THE COMMITTEE ON FOREIGN AFFAIRS HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES ONE HUNDRED FIFTEENTH CONGRESS FIRST SESSION APRIL 27, 2017 Serial No. 115–27 Printed for the use of the Committee on Foreign Affairs ( Available via the World Wide Web: http://www.foreignaffairs.house.gov/ or http://www.gpo.gov/fdsys/ U.S. GOVERNMENT PUBLISHING OFFICE 25–261PDF WASHINGTON : 2017 For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Publishing Office Internet: bookstore.gpo.gov Phone: toll free (866) 512–1800; DC area (202) 512–1800 Fax: (202) 512–2104 Mail: Stop IDCC, Washington, DC 20402–0001 VerDate 0ct 09 2002 15:39 Jun 07, 2017 Jkt 000000 PO 00000 Frm 00001 Fmt 5011 Sfmt 5011 Z:\WORK\_FULL\042717\25261 SHIRL COMMITTEE ON FOREIGN AFFAIRS EDWARD R. ROYCE, California, Chairman CHRISTOPHER H. SMITH, New Jersey ELIOT L. ENGEL, New York ILEANA ROS-LEHTINEN, Florida BRAD SHERMAN, California DANA ROHRABACHER, California GREGORY W. MEEKS, New York STEVE CHABOT, Ohio ALBIO SIRES, New Jersey JOE WILSON, South Carolina GERALD E. CONNOLLY, Virginia MICHAEL T. MCCAUL, Texas THEODORE E. DEUTCH, Florida TED POE, Texas KAREN BASS, California DARRELL E. ISSA, California WILLIAM R. KEATING, Massachusetts TOM MARINO, Pennsylvania DAVID N. CICILLINE, Rhode Island JEFF DUNCAN, South Carolina AMI BERA, California MO BROOKS, Alabama LOIS FRANKEL, Florida PAUL COOK, California TULSI GABBARD, Hawaii SCOTT PERRY, Pennsylvania JOAQUIN CASTRO, Texas RON DESANTIS, Florida ROBIN L. KELLY, Illinois MARK MEADOWS, North Carolina BRENDAN F. BOYLE, Pennsylvania TED S. YOHO, Florida DINA TITUS, Nevada ADAM KINZINGER, Illinois NORMA J. -

Download (PDF)

N° 03/2017 recherches & documents mai 2017 The Shayrat Connection: Was the Khan Shaykun Chemical Attack Inevitable but Preventable? CAN KASAPOGLU WWW . FRSTRATEGIE . ORG Édité et diffusé par la Fondation pour la Recherche Stratégique 4 bis rue des Pâtures – 75016 PARIS ISSN : 1966-5156 ISBN : 978-2-911101-96-0 EAN : 9782911101960 WWW.FRSTRATEGIE.ORG 4 BIS RUE DES PÂTURES 75 016 PARIS TÉL. 01 43 13 77 77 FAX 01 43 13 77 78 SIRET 394 095 533 00052 TVA FR74 394 095 533 CODE APE 7220Z FONDATION RECONNUE D'UTILITÉ PUBLIQUE – DÉCRET DU 26 FÉVRIER 1993 SOMMAIRE INTRODUCTION ....................................................................................................................... 5 BRIEF TECHNICAL ASSESSMENT OF THE KHAN SHAYKUN ATTACK ............................................ 6 THE CHEMICAL BLITZ .............................................................................................................. 8 THE REGIME’S TOP CHAIN OF COMMAND: MANAGING THE CHEMICAL WARFARE CAPABILITIES .. 9 MILITARY GEOSTRATEGIC CONTEXT OF THE CW USE IN SYRIA ................................................10 CARRYING OUT THE DIRTY JOB: TACTICAL LINK OF THE WMD CHAIN ......................................14 THE SUSPECTED AIR FORCE LINK ..........................................................................................14 CALLING IN THE CHEMICAL STRIKE .........................................................................................15 CONCLUSION .........................................................................................................................18 -

The CIA on Trial

The Management of Savagery The Management of Savagery How America’s National Security State Fueled the Rise of Al Qaeda, ISIS, and Donald Trump Max Blumenthal First published in English by Verso 2019 © Max Blumenthal 2019 All rights reserved The moral rights of the author have been asserted 1 3 5 7 9 10 8 6 4 2 Verso UK: 6 Meard Street, London W1F 0EG US: 20 Jay Street, Suite 1010, Brooklyn, NY 11201 versobooks.com Verso is the imprint of New Left Books ISBN-13: 978-1-78873-229-1 ISBN-13: 978-1-78873-743-2 (EXPORT) ISBN-13: 978-1-78873-228-4 (US EBK) ISBN-13: 978-1-78873-227-7 (UK EBK) British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data A catalog record for this book is available from the Library of Congress Typeset in Sabon by MJ & N Gavan, Truro, Cornwall Printed in the UK by CPI Mackays, UK Let’s remember here, the people we are fighting today, we funded twenty years ago, and we did it because we were locked in this struggle with the Soviet Union … There’s a very strong argument, which is—it wasn’t a bad investment to end the Soviet Union, but let’s be careful what we sow because we will harvest. —Secretary of State Hillary Clinton to the House Appropriations Committee, April 23, 2009 AQ [Al Qaeda] is on our side in Syria. —Jake Sullivan in February 12, 2012, email to Secretary of State Hillary Clinton We underscore that states that sponsor terrorism risk falling victim to the evil they promote. -

Armed Conflict in Syria: Overview and U.S

Armed Conflict in Syria: Overview and U.S. Response Updated September 21, 2018 Congressional Research Service https://crsreports.congress.gov RL33487 Armed Conflict in Syria: Overview and U.S. Response Summary The Syria conflict, now in its eighth year, remains a significant policy challenge for the United States. U.S. policy toward Syria in the past several years has given highest priority to counterterrorism operations against the Islamic State (IS, also known as ISIL/ISIS), but also has included nonlethal assistance to opposition-held communities, support for diplomatic efforts to reach a political settlement to the civil war, and the provision of humanitarian assistance in Syria and surrounding countries. The counter-IS campaign works primarily “by, with, and through” local partners trained, equipped, and advised by the U.S. military, per a broader U.S. strategy initiated by the Obama Administration and modified by the Trump Administration. The United States also has advocated for a political track to reach a negotiated settlement between the government of Syrian President Bashar al Asad and opposition forces, within the framework of U.N.-mediated talks in Geneva. For a brief conflict summary, see Figure 2. In November 2017, Brett McGurk, Special Presidential Envoy for the Global Coalition to Counter ISIS, stated that the United States was entering a “new phase” in its approach to Syria that would focus on “de-escalating violence overall in Syria through a combination of ceasefires and de-escalation areas.” The Administration supported de-escalation as a means of creating conditions for a national-level political dialogue among Syrians culminating in a new constitution and U.N.-supervised elections. -

SYRIA CRISIS WATCH International Strategic Studies Group (08-22 Dec 19)

© 2019 Beyond the Horizon SYRIA CRISIS WATCH International Strategic Studies Group (08-22 Dec 19) www.behorizon.org 6. At least 25,000 people fled Syria's Idlib for Turkey over two days - media. KEY EVENTS 22.12.2019 At least 25,000 civilians have fled Syria’s northwestern region of Idlib and headed towards Turkey over the past two days, Turkish state media said on Sunday, as Syrian and 1. Russian Military Opened Fire on an Israeli Aircraft. Russian forces intensified their bombardment of the region. Syrian President Bashar al-Assad has 19.12.2019 Russia has allegedly opened fire on Israeli aircraft that entered Syria’s airspace vowed to recapture Idlib, pushing more people towards Turkey. On Thursday, Turkish President in the southwestern part of the country, the Hebrew-language website Channel 12 Tayyip Erdogan said 50,000 people were fleeing from Idlib towards Syria’s border with Turkey. reported. Citing the website Top War, the Channel 12 report said the Russian military (Reuters) https://reut.rs/36YWBIB opened fire on an Israeli unmanned aerial vehicle (UAV) that was along the eastern axis of the occupied Golan Heights region. (The Syrian Observer) http://bit.ly/2PLSM3E 7. Lack of refugee aid forced Turkey into Syria operation : Erdogan. 17.12.2019 A lack of international assistance to Turkey to support millions of refugees on its soil 2. Russia & Syria Signal West With Joint Naval Drills, “Hundreds” Of Airstrikes pushed Ankara to launch operations in northeast Syria, Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdogan On Idlib. said Tuesday. Despite broad international criticism, Turkish forces in October launched a major 22.12.2019 Multiple developments related to Russia's military role in Syria mean that the cross-border raid to clear a so-called safe-zone of Kurdish fighters, who Ankara considers years-long conflict could once again become front and center for Washington during 2020. -

Implausible Denials: the Crime at Jabal Al Tharda

Implausible Denials: The Crime at Jabal al Tharda. US-led Air Raid on Behalf of ISIS-Daesh Against Syrian Forces By Prof. Tim Anderson Region: Middle East & North Africa Global Research, December 17, 2017 Theme: Media Disinformation, Terrorism, US NATO War Agenda In-depth Report: SYRIA On 17 September 2016 a carefully planned US-led air raid on Jabal al Tharda (Mount Tharda), overlooking Deir Ezzor airport, slaughtered over 100 Syrian soldiers and delivered control of the mountain to DAESH / ISIS. After that surprise attack, the terrorist group held the mountain for almost a year, but did not manage to take the airport or the entire city. US- led forces admitted the attack but claimed it was all a ‘mistake’. However uncontested facts, eye witness accounts and critical circumstances show that was a lie. This article sets out the evidence of this crime, in context of Washington’s historical use of mercenaries for covert actions, linked to the doctrine of ‘plausible deniability’. Syrian eyewitness accounts from Deir Ezzor deepen and confirm this simple fact:the US-led air raid on Syrian forces at Jabal al Tharda on 17 September 2016 was no ‘mistake’ but a well-planned and effective intervention on behalf of the terrorist group (DAESHISIS in Arabic). After days of careful surveillance a devastating missile attack followed by machine gunning of the remaining Syrian soldiers helped ISIS take control of the strategic mountain, that same day. Mercenary forces – like ISIS and the other jihadist groups in Iraq and Syria – were a staple of US intervention during the early decades of the cold war, deployed in more than 25 conflicts, such as those of the Congo, Angola and Nicaragua.