Youth Bulge Theory in the Occupied Palestinian Territories

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Malik Letter Is Protected by Copyright

TASK Organizing Monitoring Making Decisions 3 2 n 4 Providing mu icatio Objectives om n DevelopingPeople C Principles 1 of 5 Respon- New Known Known New sibility 1 7 E Effective t Systematic n Management n Abandonmenty C v Meetings C e lic or i 2 om n 6 o p r m io m o o unicat n P e G r n o e Performancec Strategy o a m 3 5 r t n v 4 i a a e te e v Appraisal r r n n n n r P o a t Reports E 07p e /12 o n Malik LettWritten er r v l Budget & c Communication oBudgeting o i e c G C y O L O S T Job-Design & for Right and Good Managem ent Assignment- Control 0 Organizational level People level Personal Personal Method Working Personal Personal Method Working Executives I Corporate Mission and Policy Control VII Assignment- Human Resources IIII Job-Design & Strategy and Management Operative Planning III T S OOL Organization long term (> 1 year) IV Communication Budgeting Budget & Annual Objectives Structure Culture Written Reports V Personal Working Method and Effectiveness Appraisal VIII 4 “Malik is (...) the leading expert Controlling VI 3 Results 5 short term (< 1 year) Performance n i c u a t m i o m n 2 6 o on Management in Europe. (...)” Meetings C short term (< 1 year) Management Abandonment Results VI Controlling Systematic Effective VIII G 1 e 7 Effectiveness overnanc Method and Peter Drucker, Doyen of Management Personal Working V C y sibility orp olic New Known Known New Annual Objectives orate P IV Respon- long term (> 1 year) Organization III Environment of Operative Planning 1 5 n o m r Strategy and i v Management e n II n II t -

The Fascist Jesus: Ernest Renan's Vie De Jésus and the Theological Origins of Fascism a Dissertation Submitted to the Un

The Fascist Jesus: Ernest Renan’s Vie de Jésus and the Theological Origins of Fascism A dissertation submitted to the University of Wales Trinity Saint David in fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Masters of Theology in Systematic and Philosophical Theology 2014 Ralph E. Lentz II UWTSD 28000845 1 Master’s Degrees by Examination and Dissertation Declaration Form. 1. This work has not previously been accepted in substance for any degree and is not being concurrently submitted in candidature for any degree. Signed……Ralph E. Lentz II Date …26 January 2014 2. This dissertation is being submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of …Masters of Theology in Systematic and Philosophical Theology……………………………………………………………................. Signed …Ralph E. Lentz II Date ……26 January 2014 3. This dissertation is the result of my own independent work/investigation, except where otherwise stated. Other sources are acknowledged by footnotes giving explicit references. A bibliography is appended. Signed candidate: …Ralph E. Lentz II Date: 26 January 2014 4. I hereby give consent for my dissertation, if accepted, to be available for photocopying, inter- library loan, and for deposit in the University’s digital repository Signed (candidate)…Ralph E. Lentz II Date…26 January 2014 Supervisor’s Declaration. I am satisfied that this work is the result of the student’s own efforts. Signed: ………………………………………………………………………….. Date: ……………………………………………………………………………... 2 Table of Contents Abstract………………………………………………………………………….4 Acknowledgements………………………………………………………………5 -

Foreword Introduction 1 the Emergence and Development Of

Notes Foreword 1. World Council of Churches/Council for World Mission (WCC-CWM), “Bringing together Ubuntu and Sangsaeng: A Journey towards Life-Giving Civilization, Transforming Theology and the Ecumenism of the 21st Century,” AfricaFiles.org, August 17, 2007, http://www.africafiles.org/article. asp?ID=15918. 2. Ulrich Duchrow and Franz Hinkelammert, Property for People, Not for Profit: Alternatives to the Global Tyranny of Capital (London and Geneva: Zed Books & World Council of Churches, 2004). 3. Ulrich Duchrow, Reinhold Bianchi, René Krüger, Vincenzo Petracca, Solidarisch Mensch werden: Psychische und soziale Destruktion im Neoliberalismus; Wege zu ihrer Überwindung (Hamburg and Oberursel: VSA in Kooperation mit Publik- Forum, 2006). Introduction 1. Dussel, Enrique: “Six Theses toward a Critique of Political Reason: The Citizen as Political Agent,” Radical Philosophy Review, 2, no. 2 (1999): 79–95. Cf. also his Hacia una filosofía política crítica (Bilbao: Desclée de Brouwer, 2001), 80. The full quote can be found on page 184 above. 1 The Emergence and Development of Division of Labor, Money, Private Property, Empire and Male Domination in Ancient and Modern Civilizations 1. F. J. Hinkelammert and H. M. Mora, Coordinación social del trabajo, mercado y reproducción de la vida humana (San José, Costa Rica: DEI, 2001), 176ff. 2. Jeremy Rifkin, The Empathic Civilization: The Race to Global Consciousness in a World in Crisis (London: Penguin, 2009), 22f. 3. Ulrich Duchrow and Franz J. Hinkelammert, Property for People, Not for Profit: Alternatives to the Global Tyranny of Capital. London and Geneva: Zed Books in association with the Catholic Institute for International Relations and the World Council of Churches, 2004. -

Money and Its Economic and Social Functions

Money and its economic and social functions Citation for published version (APA): Backhaus, J. G. (1999). Money and its economic and social functions. METEOR, Maastricht University School of Business and Economics. METEOR Research Memorandum No. 008 https://doi.org/10.26481/umamet.1999008 Document status and date: Published: 01/01/1999 DOI: 10.26481/umamet.1999008 Document Version: Publisher's PDF, also known as Version of record Please check the document version of this publication: • A submitted manuscript is the version of the article upon submission and before peer-review. There can be important differences between the submitted version and the official published version of record. People interested in the research are advised to contact the author for the final version of the publication, or visit the DOI to the publisher's website. • The final author version and the galley proof are versions of the publication after peer review. • The final published version features the final layout of the paper including the volume, issue and page numbers. Link to publication General rights Copyright and moral rights for the publications made accessible in the public portal are retained by the authors and/or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. • Users may download and print one copy of any publication from the public portal for the purpose of private study or research. • You may not further distribute the material or use it for any profit-making activity or commercial gain • You may freely distribute the URL identifying the publication in the public portal. -

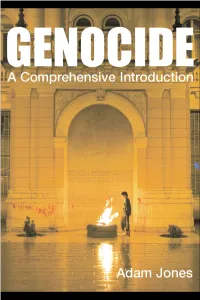

Genocide: a Comprehensive Introduction Is the Most Wide-Ranging Textbook on Geno- Cide Yet Published

■ GENOCIDE Genocide: A Comprehensive Introduction is the most wide-ranging textbook on geno- cide yet published. The book is designed as a text for upper-undergraduate and graduate students, as well as a primer for non-specialists and general readers interested in learning about one of humanity’s enduring blights. Over the course of sixteen chapters, genocide scholar Adam Jones: • Provides an introduction to genocide as both a historical phenomenon and an analytical-legal concept. • Discusses the role of imperalism, war, and social revolution in fueling genocide. • Supplies no fewer than seven full-length case studies of genocides worldwide, each with an accompanying box-text. • Explores perspectives on genocide from the social sciences, including psychology, sociology, anthropology, political science/international relations, and gender studies. • Considers “The Future of Genocide,” with attention to historical memory and genocide denial; initiatives for truth, justice, and redress; and strategies of intervention and prevention. Written in clear and lively prose, liberally sprinkled with illustrations and personal testimonies from genocide survivors, Genocide: A Comprehensive Introduction is destined to become a core text of the new generation of genocide scholarship. An accompanying website (www.genocidetext.net) features a broad selection of supplementary materials, teaching aids, and Internet resources. Adam Jones, Ph.D. is currently Associate Research Fellow in the Genocide Studies Program at Yale University. His recent publications -

Introduction: History and Its Discontents

Notes Introduction: History and Its Discontents 1. Compare Bain Attwood’s comments in ‘In the Age of Testimony: The Stolen Generations Narrative, “Distance”, and Public History’, Public Culture, 20, 1 (2008), 94–95. My thanks go to Becky Jinks for reading – and greatly improving – an earlier version of this Introduction. 2. See, for example, Lothar Kroll, Utopie als Ideologie: Geschichtsdenken und politisches HandelnimDrittenReich(Paderborn: Schöningh, 1999). 3. On the distinction between historicism in the sense of the speculative philos- ophy of history and historicism in the sense of setting events meaningfully in their historical context in the tradition of Ranke, see Frank Ankersmit, Meaning, Truth and Reference in Historical Representation (Leuven: Leuven University Press, 2012). 4. See my discussions of these issues in Chapter 12 and in ‘History, Memory, Testi- mony’, in Jane Kilby and Antony Rowland (eds.), The Future of Testimony (London: Routledge, 2013). 5. Tony Judt with Timothy Snyder, Thinking the Twentieth Century (London: William Heinemann, 2012). That does not mean I agree wholeheartedly with their partic- ular contextualisations; for example, Judt and Snyder suggest that the emergence of Holocaust consciousness in the West has buried an awareness of the sophistica- tion of Central and Eastern European history and thought, which is now regarded as interesting only insofar as it illuminates the background to and possibility of the Holocaust. Other, positive traditions have been forgotten (237). I would suggest that things are a little more complicated than that, both with respect to Holocaust consciousness – which has hardly been a uniform process in ‘the West’ – and to Western knowledge of the history of Eastern Europe. -

Nato's Demographer

REVIEWS Gunnar Heinsohn, Söhne und Weltmacht: Terror im Aufstieg und Fall der Nationen Piper: Munich 2008, €9.20, paperback 189 pp, 978 3 492 25124 2 Göran Therborn NATO’S DEMOGRAPHER Given the permanent social weight of population questions, it is remarkable that their hold on mainstream social and political discourse has been so inter- mittent and precarious. Within the academy, demography and demographic history are usually small, rather marginal disciplines, albeit duly respected for their rigour and for the brilliance of their top performers. Politically, population issues have normally been advanced from the right—and from might. They were foregrounded in mercantilist discourse on states and com- petitive power, in the dystopian political economy of Thomas Malthus and in the planning for national mass armies—particularly in France, with its avant-garde popular birth control. In the 19th-century Americas, the question was raised in the form of targeted immigration. ‘To govern is to populate’, it was said in Argentina. In Cuba and Brazil, European immigrants were perceived as an agency for the social transformation from plantation slav- ery to capitalism and commodity production, ‘whitening’ the population in the process. In North America, European immigration was the means to conquer the West. The falling European birth rates of the 1920s and 1930s induced a major concern with population across the political spectrum, from Fascism to Scandinavian Social Democracy, via ‘national government’ Britain. In Sweden, Alva and Gunnar Myrdal, the star couple of reformist modernism, managed to make population the basis of a large-scale social-policy agenda, which uniquely included easing women’s participation in the labour force 136 new left review 56 mar apr 2009 therborn: Heinsohn 137 and lifting restrictions on contraceptives, in a vast programme to promote voluntary parenthood. -

In Search of the Ideological Origins of the Holocaust

IN SEARCH OF THE IDEOLOGICAL ORIGINS OF THE HOLOCAUST Cyprian Blamires MA (Oxon) D.Phil Maryvale Institute Lecture given at the Center of European Studies and the School of Humanities and Social Sciences Pontificia Universidad Católica Madre y Maestra 25 June 2020 Good afternoon. I would like to thank Dr. Armenteros and Dr. Bello for inviting me to speak with you today. I am very sorry that I cannot be with you in person in Santo Domingo to give this conference. I look forward to coming to visit and speak on another topic at a later date. What I am going to do today is to offer a first glance at a book which I have been working on since the publication of my World Fascism: a Historical Encyclopedia .1 The subject is incredibly important, but at the same time extremly delicate. The Holocaust: one of the most horrendous atrocities in all of modern history, which consisted in the deliberate and systematic shooting, gassing, or murder by brutal neglect of human beings, men, women, children, picked up from all over Europe and sent by train to a hideous end. This war waged by Hitler and his inner cabinet against the Jews of Europe has been the object of a vast quantity of studies. However, only a relatively small number of them has addressed the central question: Why? Why did the National Socialist leaders decide not simply to enslave or rob or exploit the Jews, but actually to remove them from the face of the earth? I am a historian of ideas. -

An Empirical Analysis

A Service of Leibniz-Informationszentrum econstor Wirtschaft Leibniz Information Centre Make Your Publications Visible. zbw for Economics Lehmbecker, Philipp Working Paper The quality of eligible collateral and monetary stability: An empirical analysis ROME Discussion Paper Series, No. 08-04 Provided in Cooperation with: Research Network “Research on Money in the Economy” (ROME) Suggested Citation: Lehmbecker, Philipp (2008) : The quality of eligible collateral and monetary stability: An empirical analysis, ROME Discussion Paper Series, No. 08-04, Research On Money in the Economy (ROME), s.l. This Version is available at: http://hdl.handle.net/10419/88219 Standard-Nutzungsbedingungen: Terms of use: Die Dokumente auf EconStor dürfen zu eigenen wissenschaftlichen Documents in EconStor may be saved and copied for your Zwecken und zum Privatgebrauch gespeichert und kopiert werden. personal and scholarly purposes. Sie dürfen die Dokumente nicht für öffentliche oder kommerzielle You are not to copy documents for public or commercial Zwecke vervielfältigen, öffentlich ausstellen, öffentlich zugänglich purposes, to exhibit the documents publicly, to make them machen, vertreiben oder anderweitig nutzen. publicly available on the internet, or to distribute or otherwise use the documents in public. Sofern die Verfasser die Dokumente unter Open-Content-Lizenzen (insbesondere CC-Lizenzen) zur Verfügung gestellt haben sollten, If the documents have been made available under an Open gelten abweichend von diesen Nutzungsbedingungen die in der dort Content -

Fall 2000

WORLD WAR TWO STUDIES ASSOCIATION (formerly American Committee on the History ofthe Second World War) DOllald S. DCl\vikr. Clwimltm Mark P. Pnrillo. Secrelary 1/1111 D~pal1l11~1lt of lIislOry Ncws!£'ucr Edilor SOUl hem 1I1il\0is Ullivcrsily Dep;Ulment of History a! Clrbondalc 208 Eisenhower Hall Cubontl:1lc, Illinois 62901·4519 Knnsas Stale University tlc.'rll'ilcr~,.'",itl\l'''j'/, nct Mnnh:lllnll. KnllsDS e,65Ob-1 002 785-532-0374 Permanent Directors FJ\.'\ 785-532-7004 parillof.wKsu.ctlu Charles F. Delzell V<l.nderbill UniversilY James t.hnnnl1, Assoctmc £llilOr amI Wclmwstcr Allhur L. Funk DC'panmelll of HislOry G:linesville. Florida .:!08 Eisenhower H:l1I Kansns State University Terms £'.'Cpiring 1000 Mnnhilllall. Knns:lS 66506·1002 Cnd Boyd Robin Higham, Archivist Old Dominioll University Depanmenr of Hislory 208 Eis~nhower Hall Jalnl.·s L Cullins. Jr, NEWSLETTER Knnsns State Universily Middlebllrg, Virginia Manhalfan. Kansas 66506-1002 ISSN 0885-5668 John Lewis G~lddis The WWTSA is "JJilialetl willi: Ohio UnivtTsily Arnl:ric~ll1 J-1islOricnl Associ~lliOll Robin Higham 400 A Strct'l. S, E. Kansas State University Wn~hjllglol1, D.C, 20003 hfl/J: 1/llwlV"hcalltl,org Wan'en F Kimball No. 64 Fall 2000 Rutgers University, Nc:w<l.rk Comite lntem.uionnl d'Hislolrc de 1:1 DC:Ll~il:llll' Gucm: Mondiale AII;U1 R.Milletl Hemy ROUSSl). SccrcflIrv Gel/eml Ohio St:.l.h: University Instilu( d'Hislolrc du Temps Presenl (CcllIrc n:llional dt: In r¢eh~rchc A giles F. Peterson scielltifiqw.: lCNRSJ) J-1oo\'~r Institution Ecole Nonnale Superieure de Cachan b I, ;lVcnuc du President Wilson Russell F. -

The Failure of a Noble Experiment

PEACE THROUGH LAW? THE FAILURE OF A NOBLE EXPERIMENT Robert J. Delahunty* John C. Yoo** ALL QUIET ON THE WESTERN FRONT, By Erich Maria Remarque. A.W. Wheen trans. 1929. New York: Ballantine Books. 1982. Pp. 296. $13.95. I. THE NOVEL AND ITS RECEPTION Ever since its publication in 1929, Erich Maria Remarque's All Quiet on the Western Front has been regarded as a landmark of antiwar literature.' Appearing a decade after the end of the First World War, the novel became a literary sensation almost overnight. Within a year of publication, it had been translated into twenty languages, including Chinese, and by April 1930, sales for twelve of the twenty editions stood at 2.5 million.! Remarque was reputed to have the largest readership in the world. Hollywood took note, and an equally successful film appeared in 1930.' The success of the novel was as unexpected as it was spectacular. Read- ers across Europe had displayed little interest in books about the war throughout the • 1920s,4 but after Remarque's success, the public's appetite proved voracious. It was as if the publics of the great belligerents needed the perspective of a decade before they could begin to relive the experience of the war. The war's scale and horror are scarcely imaginable to us-indeed, they were similarly incomprehensible to those • who• 5 lived through it. The military death toll was between nine and ten million. France lost nearly one in every • Associate Professor of Law, University of St. Thomas School of Law. •* Professor of Law, UC Berkeley School of Law (Boalt Hall); Visiting Scholar, American Enterprise Institute. -

Property Economics

Property Economics Property Rights, Creditor's Money, and the Foundations of the Economy Edited by Otto Steiger Metropolis- Verlag Marburg 2008 Contents Notes on the Contributors xiii Acknowledgements xviii Property Economics: An Introduction Otto Steiger xix Note on the References xxix Part I: The Property-Based Theory of the Economy: Criticism and New Aspects The Property Theories of Bethell, Pipes, and de Soto: Similarities and Differences in Emphasis as Compared with the ,' Approach of Heinsohn, Stadermann, and Steiger , Thomas G. Betz 3 Heinsohn, Stadermann, and Steiger's "property theory of the economy" 4 Bethell's analysis of property rights in theory and history 9 Pipes's discussion of the relation between property and freedom 12 De Soto's analysis of the "missing ingredient" in developing countries 14 Similarities, differences, and conclusions 19 References 22 f I Property, Development, and Hernando de Soto's Approach: The End of Poverty Ulf Heinsohn 25 What is economic development? 26 vi Contents Property is lacking, but why is property important? 26 Orthodox and heterodox theories of development 41 Common law as an obstacle to economic development in English history 49 References 55 /The Property Approach of Heinsohn and Steiger: / Questions from an Institutionalist Viewpoint IJIans G. Nutzinger 61 Methodological problems in the distinctions between different economic concepts 61 Possession, property, and ownership: Another look from a modified institutionalist viewpoint 64 The basic elements of New Institutional Economics 66 References 67 r /Some Observations on Heinsohn and Steiger's /"Property Theory of Interest and Money": A Short Comment \Augusto Graziani 69 Heinsohn and Steiger's central points 69 Main remarks on the "property theory of interest and money" 71 References 72 / Power, the State, and the Institution of Property / Paul C.