Authenticity and Cultural Heritage in the Age of 3D Digital Reproductions

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

1. Introduction

This PDF is a simplified version of the original article published in Internet Archaeology. All links also go to the online version. Please cite this as: Nicholson, C., Fernandez, R. and Irwin, J. 2021 Digital Archaeological Data in the Wild West: the challenge of practising responsible digital data archiving and access in the United States, Internet Archaeology 58. https://doi.org/10.11141/ia.58.22 Digital Archaeological Data in the Wild West: the challenge of practising responsible digital data archiving and access in the United States Christopher Nicholson, Rachel Fernandez and Jessica Irwin Summary Archaeology in the United States is conducted by a number of different sorts of entities under a variety of legal mandates that lack uniform standards for data archiving. The difficulty of accessing data from projects in which one was not directly involved indicates an apparent reluctance to archive raw data and supplemental information with digital repositories to be reused in the future. There is hope that additional legislation, guidelines from professional organisations, and educational efforts will change these practices. 1. Introduction Though we are well into the 21st century, responsible digital archiving of archaeological data in the United States is not common practice. Digital archiving of cultural resource management reports in State Historic Preservation Offices, where they are often available by request though perhaps at a cost, is common; however, digitally archiving the datasets and other supporting materials that went into the creation of those documents is not. Though a vocal minority advocates for responsible digital archiving practices (Kansa and Kansa 2013; 2018; Kansa et al. -

Digital Reconstruction of an Archaeological Site Based on the Integration of 3D Data and Historical Sources

International Archives of the Photogrammetry, Remote Sensing and Spatial Information Sciences, Volume XL-5/W1, 2013 3D-ARCH 2013 - 3D Virtual Reconstruction and Visualization of Complex Architectures, 25 – 26 February 2013, Trento, Italy DIGITAL RECONSTRUCTION OF AN ARCHAEOLOGICAL SITE BASED ON THE INTEGRATION OF 3D DATA AND HISTORICAL SOURCES G. Guidi a, *, M. Russo b, D. Angheleddu a a Dept. of Mechanics, Politecnico di Milano, Italy (gabriele.guidi, davide.angheleddu)@polimi.it b Dept. of Design, Politecnico di Milano, Italy [email protected] Commission V, WG V/4 KEY WORDS: 3D survey, archaeological sites, reality based modeling, digital reconstruction, integration of methods, Cham Architecture ABSTRACT: The methodology proposed in this paper in based on an integrated approach for creating a 3D digital reconstruction of an archaeological site, using extensively the 3D documentation of the site in its current state, followed by an iterative interaction between archaeologists and digital modelers, leading to a progressive refinement of the reconstructive hypotheses. The starting point of the method is the reality-based model, which, together with ancient drawings and documents, is used for generating the first reconstructive step. Such rough approximation of a possible architectural structure can be annotated through archaeological considerations that has to be confronted with geometrical constraints, producing a reduction of the reconstructive hypotheses to a limited set, each one to be archaeologically evaluated. This refinement loop on the reconstructive choices is iterated until the result become convincing by both points of view, integrating in the best way all the available sources. The proposed method has been verified on the ruins of five temples in the My Son site, a wide archaeological area located in central Vietnam. -

Methods in Digital Archaeology and Cultural Heritage Katy Meyers Emery

Methods in Digital Archaeology and Cultural Heritage Katy Meyers Emery Increasingly over the last decade, anthropologists have looked to digital tools as a way to improve their interpretations, engage with the public and other professionals, collaborate with other disciplines, develop new technology to improve the discipline and more. Due to the increasing importance of digital, it is important that current students become equipped with the skills and confidence necessary to creatively and thoughtfully apply digital tools to cultural heritage questions. With that in mind, this course is not a lecture- it is an open discussion and development course where students will learn digital tools by using and making them. This course will provide students with an introduction to digital tools in archaeology, from using social media to engage with communities to developing their own online projects to preserve, protect, share and engage with cultural heritage and archaeology. Course Goals: 1. Understand and articulate the benefits and challenges of digital methods within archaeology and cultural heritage management 2. Critically use digital methods to engage with the public and archaeological community online to promote cultural and archaeological heritage and preservation (ex. Blogging, Twitter, Digital Mapping, etc) 3. Leverage digital tools to create a digital project focused on archaeology or cultural heritage Texts: All reading material for this course will be provided online, although students may need to request or find their own reading material related to a historic site for their final project. **This syllabus was designed based on a course that I helped develop and teach over summer 2014, a Mobile Cultural Heritage Informatics class I assisted in during summer 2011, and my years as a Cultural Heritage Informatics Initiative fellow. -

Art: Authenticity, Restoration, Forgery

UCLA Cotsen Institute of Archaeology Press Title Art: Authenticity, Restoration, Forgery Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/5xf6b5zd ISBN 978-1-938770-08-1 Author Scott, David A. Publication Date 2016-12-01 Data Availability The data associated with this publication are within the manuscript. Peer reviewed eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California READ ONLY/NO DOWNLOADS Art: Art: Authenticity, Restoration, ForgeryRestoration, Authenticity, Art: Forgery Authenticity, Restoration, Forgery David A. Scott his book presents a detailed account of authenticity in the visual arts from the Palaeolithic to the postmodern. The restoration of works Tof art can alter the perception of authenticity, and may result in the creation of fakes and forgeries. These interactions set the stage for the subject of this book, which initially examines the conservation perspective, then continues with a detailed discussion of what “authenticity” means, and the philosophical background. Included are several case studies that discuss conceptual, aesthetic, and material authenticity of ancient and modern art in the context of restoration and forgery. • Scott Above: An artwork created by the author as a conceptual appropriation of the original Egyptian faience objects. Do these copies possess the same intangible authenticity as the originals? Photograph by David A. Scott On front cover: Cast of author’s hand with Roman mask. Photograph by David A. Scott MLKRJBKQ> AO@E>BLILDF@> 35 MLKRJBKQ> AO@E>BLILDF@> 35 CLQPBK IKPQFQRQB LC AO@E>BLILDV POBPP CLQPBK IKPQFQRQB LC AO@E>BLILDV POBPP CIoA Press READ ONLY/NO DOWNLOADS Art: Authenticity, Restoration, Forgery READ ONLY/NO DOWNLOADS READ ONLY/NO DOWNLOADS Art: Authenticity, Restoration, Forgery David A. -

DIGITAL ARCHAEOLOGY of HERITAGE BUILDINGS of WEST AFRICA Ghana – 28 May – 1 July

NEW Summer 2017 Field School in DIGITAL ARCHAEOLOGY OF HERITAGE BUILDINGS OF WEST AFRICA Ghana – 28 May – 1 July Focusing on the Elmina Castle (1482, Ghana) the school introduces the principles of structural diagnostics of heritage masonry buildings with the aim to produce a systematic survey (manual, photogrammetric, laser scanning, aerial drone photography) and related digital reconstructions of select areas of the Castle. The school also fosters the understanding of the historical environment, and in particular the pivotal role in the Transatlantic World, of Elmina Castle through study visits to other forts and castles in coastal Ghana. In addition, the school offers a broader view of Ghana’s natural and cultural heritage through guided visits to selected archaeological sites and national parks. There are no pre-requisites. The field school is designed to attract undergraduate and graduate students in the humanities, social sciences, and engineering interested in acquiring skills in a multidisciplinary environment. Faculty: Prof. Renato Perucchio, Co-director – Mechanical Engineering and Director, Archaeology Technology and Historical Structures, University of Rochester – [email protected] ; Prof. Kodzo Gavua, Co-director – Archaeology and Heritage Studies and Dean, School of Arts, College of Humanities, University of Ghana - [email protected] ; Prof. Michael Jarvis, History and Director, Digital Media Studies, University of Rochester - [email protected] ; and Prof. William Gblerkpor, Archaeology and Heritage -

Monumental Computations. Digital Archaeology of Large Urban And

Visualising the Past through the Virtual Image Virtual Reconstitutions as interpretations of knowledge Tiago CRUZ, University of Porto, Portugal Abstract: The image has the power to mean something, to tell, to express, to represent, and to present. Based on a reflection upon the place of the virtual image in the visuali- sation of the past, the present article seeks to answer to the transformations that result from the digital revolution, with implications in our relationship with History and in our experience of the built heritage. With the aim of returning the old Convent of Monchique to the city of Porto (Portugal) and its community, the interpretation of knowledge is ex- plored here by using the virtual image as an instrument for the visualisation of the past, in its visibilities and invisibilities, through interpretative exercises of the past, guided by historical accuracy, authenticity, and scientific transparency. Due to the profound formal and functional changes it has undergone over time—even prior to its foundation, in the 16th century, and up to the present—, the convent presents itself as an ideal example to test the use of scientific methodologies and their validity in an interpretative visualisation of the past. Keywords: Virtual image—digital reconstruction—data authenticity—uncertain data— reconstructions CHNT Reference: Tiago Cruz. 2021. Visualising the Past through the Virtual Image. Börner, Wolf- gang; Kral-Börner, Christina, and Rohland, Hendrik (eds.), Monumental Computations: Digital Ar- chaeology of Large Urban and Underground Infrastructures. Proceedings of the 24th International Conference on Cultural Heritage and New Technologies, held in Vienna, Austria, November 2019. Heidelberg: Propylaeum. -

Use of Photogrammetry for Digital Surveying, Documentation and Communication of Cultural Heritage

Use of Photogrammetry for Digital Surveying, Documentation and Communication of Cultural Heritage. The Case of Virtual Reconstruction of the Access Doors for the Nameless Temple of Tipasa (Algeria) BAYA BENNOUI-LADRAA, National Center for Archaeological Research, Algeria YOUCEF CHENNAOUI, Polytechnic School of Architecture and Urbanism, Algeria This paper presents a methodological contribution to the field of the process of archaeological restoration based on virtual anastylosis. In particular, we treat the reconstruction of fragments of the nameless Temple of Tipasa in Algeria. Our work is focused more specifically on the virtual restoration of the three access doors into the temple’s sacred courtyard. Here, we have found many fragments, including the voussoirs, which were revealed during excavation, encouraging the development of our hypothesis about the original condition of the temple. The protocol followed is based on the photogrammetric survey of the blocks, which has allowed us to generate 3D models of the elements constituting the entrance facade into the sacred courtyard. The historical documentation as well as architectural treatises made it possible to fill in the gaps in the evidence with the aim of reconstructing the temple as best as can be done. The main objective of the research was to provide a corpus of data in 2D and 3D of all the blocks which served, at first, for the documentation and the study of the remains. Secondarily, the same documentation proved useful for development of a hypothesis of virtual reconstitution for making more comprehensible to the general public the history of the site of Tipasa. Key words: Photogrammetry, 3D Reconstruction, Virtual Anastylosis, Corpus, Temple. -

Mitigating the Curation Crisis of the 21St Century

A California Case Study on Procedures to Reassemble and Reevaluate Archaeological Artifact Processing: Mitigating the Curation Crisis of the 21st Century By Allysha A. Leonard Senior Thesis Advisor: Tsim Schneider Submitted to the Department of Anthropology University of California Santa Cruz Santa Cruz, CA 95060 3/20/19 In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Bachelor’s in Anthropology Table of Contents Table of Contents ............................................................................................................................ 2 I. Abstract ........................................................................................................................................ 3 II. Introduction ................................................................................................................................ 6 Background in Under Processing: Lack of Analysis .................................................................. 8 Background in Over Processing: Artifact Hoarding and Lack of Ethical Deaccessioning ........ 9 Defining Waste and Defects in the Artifact Process ................................................................. 16 Defining Lean Systems and Kaizen Waste Improvement Strategies ........................................ 17 III. Methods and Case Studies ...................................................................................................... 21 A “A Reality Check” — Field Lab and CRM Experience: Sesnon House, Cabrillo College, Soquel, CA ............................................................................................................................... -

The Licit and the Illicit in Archaeological and Heritage Discourses

CHALLENGING THE DICHOTOMY EDIT ED BY LES FIELD CRISTÓBAL GNeccO JOE WATKINS CHALLENGING THE DICHOTOMY • The Licit and the Illicit in Archaeological and Heritage Discourses TUCSON The University of Arizona Press www.uapress.arizona.edu © 2016 by The Arizona Board of Regents Open-access edition published 2020 ISBN-13: 978-0-8165-3130-1 (cloth) ISBN-13: 978-0-8165-4169-0 (open-access e-book) The text of this book is licensed under the Creative Commons Atrribution- NonCommercial-NoDerivsatives 4.0 (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0), which means that the text may be used for non-commercial purposes, provided credit is given to the author. For details go to http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/. Cover designed by Leigh McDonald Publication of this book is made possible in part by the Wenner-Gren Foundation. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Names: Field, Les W., editor. | Gnecco, Cristóbal, editor. | Watkins, Joe, 1951– editor. Title: Challenging the dichotomy : the licit and the illicit in archaeological and heritage discourses / edited by Les Field, Cristóbal Gnecco, and Joe Watkins. Description: Tucson : The University of Arizona Press, 2016. | Includes bibliographical references and index. Identifiers: LCCN 2016007488 | ISBN 9780816531301 (cloth : alk. paper) Subjects: LCSH: Archaeology. | Archaeology and state. | Cultural property—Protection. Classification: LCC CC65 .C47 2016 | DDC 930.1—dc23 LC record available at https:// lccn.loc.gov/2016007488 An electronic version of this book is freely available, thanks to the support of libraries working with Knowledge Unlatched. KU is a collaborative initiative designed to make high quality books Open Access for the public good. -

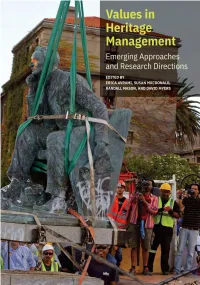

Values in Heritage Management

Values in Heritage Management Values in Heritage Management Emerging Approaches and Research Directions Edited by Erica Avrami, Susan Macdonald, Randall Mason, and David Myers THE GETTY CONSERVATION INSTITUTE, LOS ANGELES The Getty Conservation Institute Timothy P. Whalen, John E. and Louise Bryson Director Jeanne Marie Teutonico, Associate Director, Programs The Getty Conservation Institute (GCI) works internationally to advance conservation practice in the visual arts—broadly interpreted to include objects, collections, architecture, and sites. The Institute serves the conservation community through scientific research, education and training, field projects, and the dissemination of information. In all its endeavors, the GCI creates and delivers knowledge that contributes to the conservation of the world’s cultural heritage. © 2019 J. Paul Getty Trust Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Names: Values in heritage management (2017 : Getty Conservation Institute), author. | Avrami, Erica C., editor. | Getty Conservation Institute, The text of this work is licensed under a Creative issuing body, host institution, organizer. Commons Attribution-NonCommercial- Title: Values in heritage management : emerging NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. To view a approaches and research directions / edited by copy of this license, visit https://creativecommons Erica Avrami, Susan Macdonald, Randall .org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/. All images are Mason, and David Myers. reproduced with the permission of the rights Description: Los Angeles, California : The Getty holders acknowledged in captions and are Conservation Institute, [2019] | Includes expressly excluded from the CC BY-NC-ND license bibliographical references. covering the rest of this publication. These images Identifiers: LCCN 2019011992 (print) | LCCN may not be reproduced, copied, transmitted, or 2019013650 (ebook) | ISBN 9781606066201 manipulated without consent from the owners, (epub) | ISBN 9781606066188 (pbk.) who reserve all rights. -

AAA2021 Session Themes V2

SESSION THEMES After Archaeology in Practice: Student Research in Archaeology and Cultural Heritage Management An extraordinary and excitingly diverse range of research topics are pursued by students in archaeology and cultural heritage management and with the advent of covid-19, students have engaged with history, science and culture in ways we haven’t even begun to fully explore. Disseminating your research results to an audience of archaeologists at Australia’s annual conference was a huge hit at the 2019 AAA Conference on the Gold Coast and by request we propose to run a student-led and focussed session for the 2021 AAA conference. This session focusses on student research and provides an opportunity to speak alongside a group of your peers in a safe moderated space. We support and encourage student researchers at all levels to present a paper on their research in any area of archaeology and cultural heritage management from national and international contexts. Presenting in this forum allows you to develop important skills at communicating your research results. Presentations will be a maximum of 10-15minutes with 5 minutes for questions. Archaeological Science Collaborations: The ARCAS Network Session Archaeological science has become an integral part of Australian archaeology, with advancements in technologies allowing new types of data and/or higher resolution data to be produced. These data underpin detailed and nuanced interpretations of past human behaviour and contribute to understanding how people lived on Country. Archaeological science, with its foundations in western science, can play an important role in reconciliation and truth telling, especially when combined with the traditional knowledges of First Nation people. -

JURN : the Directory of Scholarly Ejournals in The

Search and retrieve JURN directory full-text from all these ejournals, at JURN An organised links directory for the arts & humanities, listing selected open access or otherwise free ejournals. This is a partial listing of English-language journals indexed by the JURN search-engine, now searching over 4,000 ejournals in the arts & humanities. JURN uses article URLs, rather than the front-page URLs used in this directory. Directory updated: 9th December 2018. © 2018. All links in this directory were checked and working at: 9th December 2018. For best results please view in widescreen, or else the 3rd and 4th columns may be very narrow. Architecture and place History : general Literature : literary criticism Feminist studies A|Z : ITU Journal of Faculty of Architecture. Agricultural History Society journal. After All. 19th Century Gender Studies. A+B : Architecture and the Built Environment . Associated Students for Historic Preserv ation (ASHP) journal. Alicante Journal of English Studies. Catalyst : Feminism, Theory, T echnoscience. ABE : architecture beyond Europe. Athens Journal of History. Anglica : Int. J. of English Studies. Diotema : women and gender in the ancient world. Aether : journal of media geograph y. British Numismatic Journal . Anglo Saxonica. Feminists Against Censorship newsletter. Alam al-Bina. Built Heritage. ABO : ... Women in the Arts, 1640-1830. Feminist Europa : review of books. Architecture W eek. ChildCult (History of childhood). Apollonian, The. Films for the Feminist Classroom. Architectural Histories . Cliodynamics. At The Edge. Journal of Interdisciplinary Feminist Thought. Archnet-IJAR : International Journal of Architectural Research. Comparative Civilizations Review. Athens Journal of Philology. Kapralova Society Journal : a journal of women in music.