Nabonidus, Belshazzar, and the Book of Daniel: an Update

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Download PDF Version of Article

STUDIA ORIENTALIA PUBLISHED BY THE FINNISH ORIENTAL SOCIETY 106 OF GOD(S), TREES, KINGS, AND SCHOLARS Neo-Assyrian and Related Studies in Honour of Simo Parpola Edited by Mikko Luukko, Saana Svärd and Raija Mattila HELSINKI 2009 OF GOD(S), TREES, KINGS AND SCHOLARS clay or on a writing board and the other probably in Aramaic onleather in andtheotherprobably clay oronawritingboard ME FRONTISPIECE 118882. Assyrian officialandtwoscribes;oneiswritingincuneiformo . n COURTESY TRUSTEES OF T H E BRITIS H MUSEUM STUDIA ORIENTALIA PUBLISHED BY THE FINNISH ORIENTAL SOCIETY Vol. 106 OF GOD(S), TREES, KINGS, AND SCHOLARS Neo-Assyrian and Related Studies in Honour of Simo Parpola Edited by Mikko Luukko, Saana Svärd and Raija Mattila Helsinki 2009 Of God(s), Trees, Kings, and Scholars: Neo-Assyrian and Related Studies in Honour of Simo Parpola Studia Orientalia, Vol. 106. 2009. Copyright © 2009 by the Finnish Oriental Society, Societas Orientalis Fennica, c/o Institute for Asian and African Studies P.O.Box 59 (Unioninkatu 38 B) FIN-00014 University of Helsinki F i n l a n d Editorial Board Lotta Aunio (African Studies) Jaakko Hämeen-Anttila (Arabic and Islamic Studies) Tapani Harviainen (Semitic Studies) Arvi Hurskainen (African Studies) Juha Janhunen (Altaic and East Asian Studies) Hannu Juusola (Semitic Studies) Klaus Karttunen (South Asian Studies) Kaj Öhrnberg (Librarian of the Society) Heikki Palva (Arabic Linguistics) Asko Parpola (South Asian Studies) Simo Parpola (Assyriology) Rein Raud (Japanese Studies) Saana Svärd (Secretary of the Society) -

The Assyrian Period the Nee-Babylonian Period

and ready to put their ban and curse on any intruder. A large collection of administrative documents of the Cassite period has been found at Nippur. The Assyrian Period The names of the kings of Assyria who reigned in the great city of Nineveh in the eighth and seventh centuries until its total destruction in 606 B.C. have been made familiar to us through Biblical traditions concerning the wars of Israel and Juda, the siege of Samaria and Jeru- salem, and even the prophet Jonah. From the palaces at Calah, Nineveh, Khorsabad, have come monumental sculptures and bas-reliefs, historical records on alabaster slabs and on clay prisms, and the many clay tab- lets from the royal libraries. Sargon, Sennacherib, Esarhaddon, Ashur- banipal- the Sardanapalus of the Greeks- carried their wars to Baby- lonia, to Elam, to the old Sumerian south on the shores of the Persian Gulf. Babylon became a province of the Assyrian Empire under the king's direct control, or entrusted to the hand of a royal brother or even to a native governor. The temples were restored by their order. Bricks stamped with the names of the foreign rulers have been found at Nip- pur, Kish, Ur and other Babylonian cities, and may be seen in the Babylonian Section of the University Museum. Sin-balatsu-iqbi was governor of Ur and a devoted servant of Ashurbanipal. The temple of Nannar was a total ruin. He repaired the tower, the enclosing wall, the great gate, the hall of justice, where his inscribed door-socket, in the shape of a green snake, was still in position. -

Republic of Iraq

Republic of Iraq Babylon Nomination Dossier for Inscription of the Property on the World Heritage List January 2018 stnel oC fobalbaT Executive Summary .......................................................................................................................... 1 State Party .......................................................................................................................................................... 1 Province ............................................................................................................................................................. 1 Name of property ............................................................................................................................................... 1 Geographical coordinates to the nearest second ................................................................................................. 1 Center ................................................................................................................................................................ 1 N 32° 32’ 31.09”, E 44° 25’ 15.00” ..................................................................................................................... 1 Textural description of the boundary .................................................................................................................. 1 Criteria under which the property is nominated .................................................................................................. 4 Draft statement -

Kings & Events of the Babylonian, Persian and Greek Dynasties

KINGS AND EVENTS OF THE BABYLONIAN, PERSIAN, AND GREEK DYNASTIES 612 B.C. Nineveh falls to neo-Babylonian army (Nebuchadnezzar) 608 Pharaoh Necho II marched to Carchemesh to halt expansion of neo-Babylonian power Josiah, King of Judah, tries to stop him Death of Josiah and assumption of throne by his son, Jehoahaz Jehoiakim, another son of Josiah, replaced Jehoahaz on the authority of Pharaoh Necho II within 3 months Palestine and Syria under Egyptian rule Josiah’s reforms dissipate 605 Nabopolassar sends troops to fight remaining Assyrian army and the Egyptians at Carchemesh Nebuchadnezzar chased them all the way to the plains of Palestine Nebuchadnezzar got word of the death of his father (Nabopolassar) so he returned to Babylon to receive the crown On the way back he takes Daniel and other members of the royal family into exile 605 - 538 Babylon in control of Palestine, 597; 10,000 exiled to Babylon 586 Jerusalem and the temple destroyed and large deportation 582 Because Jewish guerilla fighters killed Gedaliah another last large deportation occurred SUCCESSORS OF NEBUCHADNEZZAR 562 - 560 Evil-Merodach released Jehoiakim (true Messianic line) from custody 560 - 556 Neriglissar 556 Labaski-Marduk reigned 556 - 539 Nabonidus: Spent most of the time building a temple to the mood god, Sin. This earned enmity of the priests of Marduk. Spent the rest of his time trying to put down revolts and stabilize the kingdom. He moved to Tema and left the affairs of state to his son, Belshazzar Belshazzar: Spent most of his time trying to restore order. Babylonia’s great threat was Media. -

Gilgamesh Sung in Ancient Sumerian Gilgamesh and the Ancient Near East

Gilgamesh sung in ancient Sumerian Gilgamesh and the Ancient Near East Dr. Le4cia R. Rodriguez 20.09.2017 ì The Ancient Near East Cuneiform cuneus = wedge Anadolu Medeniyetleri Müzesi, Ankara Babylonian deed of sale. ca. 1750 BCE. Tablet of Sargon of Akkad, Assyrian Tablet with love poem, Sumerian, 2037-2029 BCE 19th-18th centuries BCE *Gilgamesh was an historic figure, King of Uruk, in Sumeria, ca. 2800/2700 BCE (?), and great builder of temples and ci4es. *Stories about Gilgamesh, oral poems, were eventually wriXen down. *The Babylonian epic of Gilgamesh compiled from 73 tablets in various languages. *Tablets discovered in the mid-19th century and con4nue to be translated. Hero overpowering a lion, relief from the citadel of Sargon II, Dur Sharrukin (modern Khorsabad), Iraq, ca. 721–705 BCE The Flood Tablet, 11th tablet of the Epic of Gilgamesh, Library of Ashurbanipal Neo-Assyrian, 7th century BCE, The Bri4sh Museum American Dad Gilgamesh and Enkidu flank the fleeing Humbaba, cylinder seal Neo-Assyrian ca. 8th century BCE, 2.8cm x 1.3cm, The Bri4sh Museum DOUBLING/TWINS BROMANCE *Role of divinity in everyday life. *Relaonship between divine and ruler. *Ruler’s asser4on of dominance and quest for ‘immortality’. StatuePes of two worshipers from Abu Temple at Eshnunna (modern Tell Asmar), Iraq, ca. 2700 BCE. Gypsum inlaid with shell and black limestone, male figure 2’ 6” high. Iraq Museum, Baghdad. URUK (WARKA) Remains of the White Temple on its ziggurat. Uruk (Warka), Iraq, ca. 3500–3000 BCE. Plan and ReconstrucVon drawing of the White Temple and ziggurat, Uruk (Warka), Iraq, ca. -

Hammurabi's Code

Hammurabi’s Code: Was It Just? Nearly 4,000 years ago, a man named Euphrates rivers. Hammurabi became king of a small city-state called Babylon. Today Babylon exists only as an After his victories at Larsa and Mari, archaeological site in central Iraq. But in Hammurabi's thoughts of war gave way to Hammurabi's time, it was the capital of the thoughts of peace. These, in turn, gave way to kingdom of Babylonia. thoughts of justice. In the 38th year of his rule, Hammurabi had 282 laws carved on a large, pillar- We know little about Hammurabi's like stone called a stele. Together, these laws have personal life. We don't know his birth date, how been called Hammurabi's Code. Historians believe many wives and children he had, or how and that several of these inscribed steles were placed when he died. We aren't even sure around the kingdom, though only what he looked like. However, one has been found intact. thanks to thousands of clay writing tablets that have been found by Hammurabi was not the first archaeologists, we know something Mesopotamian ruler to put his laws about Hammurabi's military into writing, but his code is the campaigns and his dealings with most complete. By studying his surrounding city-states. We also laws, historians have been able to know quite about every day life in get a good picture of many aspects Babylonia. of Babylonian society - work and family life, social structures, trade The tablets tell us that and government. For example, we Hammurabi ruled for 42 years. -

Neo Babylonian Rule

Neo Babylonians Rule “The Most Accomplished Empire” *Clears throat* Thank you. Thank you ever so much distinguished colleagues and professors for inviting me to speak to you today. As many of you know I'm professor Olivia Eichman of archeological studies at Stanford University. I have also worked at various dig sites in ancient sumers regions. All of these excavations lead me to countless degrees in antiquity. Enough about me already, I'm here to talk to you about about the great Mesopotamian Empires. But which empire was the greatest? Was it the Akkadians with the first empire? Or the Assyrians who reigned the longest? Neither of these empires strike me as the most accomplished. The Neo Babylonian’s Empire was the most accomplished empire by far and when you leave this room today I guarantee you will think as highly of them as I do too. Why do I think that the Neo Babylonians are the most accomplished? For starters, their ruler knew how to keep his empire safe. He had many safety precautions. One way Nebuchadrezzar II insured safety among his people was by surrounding their city in a wall so great in size two chariots could ride on it side by side. But that isn't all. No. Nebuchadnezzar II built another wall inside of the other wall for added protection. Both walls were named after Mesopotamian gods and goddesses. One of the gates that was built was called Ishtar gate, named after the goddess of war and love. To top it all off the walls were surrounded by a moat. -

The Evolution of Fragility: Setting the Terms

McDONALD INSTITUTE CONVERSATIONS The Evolution of Fragility: Setting the Terms Edited by Norman Yoffee The Evolution of Fragility: Setting the Terms McDONALD INSTITUTE CONVERSATIONS The Evolution of Fragility: Setting the Terms Edited by Norman Yoffee with contributions from Tom D. Dillehay, Li Min, Patricia A. McAnany, Ellen Morris, Timothy R. Pauketat, Cameron A. Petrie, Peter Robertshaw, Andrea Seri, Miriam T. Stark, Steven A. Wernke & Norman Yoffee Published by: McDonald Institute for Archaeological Research University of Cambridge Downing Street Cambridge, UK CB2 3ER (0)(1223) 339327 [email protected] www.mcdonald.cam.ac.uk McDonald Institute for Archaeological Research, 2019 © 2019 McDonald Institute for Archaeological Research. The Evolution of Fragility: Setting the Terms is made available under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial- NoDerivatives 4.0 (International) Licence: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/ ISBN: 978-1-902937-88-5 Cover design by Dora Kemp and Ben Plumridge. Typesetting and layout by Ben Plumridge. Cover image: Ta Prohm temple, Angkor. Photo: Dr Charlotte Minh Ha Pham. Used by permission. Edited for the Institute by James Barrett (Series Editor). Contents Contributors vii Figures viii Tables ix Acknowledgements x Chapter 1 Introducing the Conference: There Are No Innocent Terms 1 Norman Yoffee Mapping the chapters 3 The challenges of fragility 6 Chapter 2 Fragility of Vulnerable Social Institutions in Andean States 9 Tom D. Dillehay & Steven A. Wernke Vulnerability and the fragile state -

The Destruction of Sennacherib

Get hundreds more LitCharts at www.litcharts.com The Destruction of Sennacherib the sleeping army. The Angel breathed in the faces of the POEM TEXT Assyrians. They died as they slept, and the next morning their eyes looked cold and dead. Their hearts beat once in resistance 1 The Assyrian came down like the wolf on the fold, to the Angel of Death, then stopped forever. 2 And his cohorts were gleaming in purple and gold; One horse lay on the ground with wide nostrils—wide not 3 And the sheen of their spears was like stars on the sea, because he was breathing fiercely and proudly like he normally did, but because he was dead. Foam from his dying breaths had 4 When the blue wave rolls nightly on deep Galilee. gathered on the ground. It was as cold as the foam on ocean waves. 5 Like the leaves of the forest when Summer is green, 6 That host with their banners at sunset were seen: The horse's rider lay nearby, in a contorted pose and with 7 Like the leaves of the forest when Autumn hath blown, deathly pale skin. Morning dew had gathered on his forehead, and his armor had already started to rust. No noise came from 8 That host on the morrow lay withered and strown. the armies' tents. There was no one to hold their banners or lift their spears or blow their trumpets. 9 For the Angel of Death spread his wings on the blast, 10 And breathed in the face of the foe as he passed; In the Assyrian capital of Ashur, the wives of the dead Assyrian soldiers wept loudly for their husbands. -

The Neo-Babylonian Empire New Babylonia Emerged out of the Chaos That Engulfed the Assyrian Empire After the Death of the Akka

NAME: DATE: The Neo-Babylonian Empire New Babylonia emerged out of the chaos that engulfed the Assyrian Empire after the death of the Akkadian king, Ashurbanipal. The Neo-Babylonian Empire extended across Mesopotamia. At its height, the region ruled by the Neo-Babylonian kings reached north into Anatolia, east into Persia, south into Arabia, and west into the Sinai Peninsula. It encompassed the Fertile Crescent and the Tigris and Euphrates River valleys. New Babylonia was a time of great cultural activity. Art and architecture flourished, particularly under the reign of Nebuchadnezzar II, was determined to rebuild the city of Babylonia. His civil engineers built temples, processional roadways, canals, and irrigation works. Nebuchadnezzar II sought to make the city a testament not only to Babylonian greatness, but also to honor the Babylonian gods, including Marduk, chief among the gods. This cultural revival also aimed to glorify Babylonia’s ancient Mesopotamian heritage. During Assyrian rule, Akkadian language had largely been replaced by Aramaic. The Neo-Babylonians sought to revive Akkadian as well as Sumerian-Akkadian cuneiform. Though Aramaic remained common in spoken usage, Akkadian regained its status as the official language for politics and religious as well as among the arts. The Sumerian-Akkadian language, cuneiform script and artwork were resurrected, preserved, and adapted to contemporary uses. ©PBS LearningMedia, 2015 All rights reserved. Timeline of the Neo-Babylonian Empire 616 Nabopolassar unites 575 region as Neo- Ishtar Gate 561 Amel-Marduk becomes king. Babylonian Empire and Walls of 559 Nerglissar becomes king. under Babylon built. 556 Labashi-Marduk becomes king. Chaldean Dynasty. -

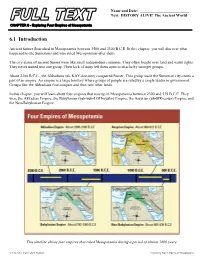

Text: HISTORY ALIVE! the Ancient World

Name and Date: _________________________ Text: HISTORY ALIVE! The Ancient World 6.1 Introduction Ancient Sumer flourished in Mesopotamia between 3500 and 2300 B.C.E. In this chapter, you will discover what happened to the Sumerians and who ruled Mesopotamia after them. The city-states of ancient Sumer were like small independent countries. They often fought over land and water rights. They never united into one group. Their lack of unity left them open to attacks by stronger groups. About 2300 B.C.E., the Akkadians (uh-KAY-dee-unz) conquered Sumer. This group made the Sumerian city-states a part of an empire. An empire is a large territory where groups of people are ruled by a single leader or government. Groups like the Akkadians first conquer and then rule other lands. In this chapter, you will learn about four empires that rose up in Mesopotamia between 2300 and 539 B.C.E. They were the Akkadian Empire, the Babylonian (bah-buh-LOH-nyuhn) Empire, the Assyrian (uh-SIR-ee-un) Empire, and the Neo-Babylonian Empire. This timeline shows four empires that ruled Mesopotamia during a period of almost 1800 years. © Teachers’ Curriculum Institute Exploring Four Empires of Mesopotamia Name and Date: _________________________ Text: HISTORY ALIVE! The Ancient World 6.2 The Akkadian Empire For 1,200 years, Sumer was a land of independent city-states. Then, around 2300 B.C.E., the Akkadians conquered the land. The Akkadians came from northern Mesopotamia. They were led by a great king named Sargon. Sargon became the first ruler of the Akkadian Empire. -

Fertile Crescent.Pdf

Fertile Crescent The Earliest Civilization! Climate Change … For Real. ➢ Climate not what it is like today. ➢ In Ancient times weather was good, the soil fertile and the irrigation system well managed, civilisation grew and prospered. ➢ Deforestation - The most likely cause of climate changing in the fertile crescent. ➢ Massive forest have their weather patterns. Ground temperature is lower. More biodiversity. Today vs. Ancient Times Map of the Fertile Crescent A day in the fertile crescent. Rivers Support the Growth of Civilization Near the Tigris and Euphrates Surplus Lead to Societal Growth Summary Mesopotamia’s rich, fertile lands supported productive farming, which led to the development of cities. In the next section you will learn about some of the first city builders. Where was Mesopotamia? How did the Fertile Crescent get its name? What was the most important factor in making Mesopotamia’s farmland fertile? Why did farmers need to develop a system to control their water supply? In what ways did a division of labor contribute to the growth of Mesopotamian civilization? How might running large projects prepare people for running a government? Early Civilizations By Rivers. Mesopotamia The land between the rivers. Religion: Great Ideas: Great Men: Geography: Major Events: Cultural Values: Structure of the Notes! Farming Lead to Division of Labor Although Mesopotamia had fertile soil, Farmers could produce a food surplus, or farming wasn’t easy there. The region more than they needed.Farmers also used received little rain.This meant that the water irrigation to water grazing areas for cattle and levels in the Tigris and Euphrates rivers sheep.