Terry Pratchett's Witches

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Jacquelyn Bent and Helen Gavin

University of Huddersfield Repository Bent, Jacqi and Gavin, Helen The Maids, Mother and “The Other One” of the Discworld: Exploring the magical aspect of Terry Pratchett's Witches. Original Citation Bent, Jacqi and Gavin, Helen (2010) The Maids, Mother and “The Other One” of the Discworld: Exploring the magical aspect of Terry Pratchett's Witches. In: 1st Global Conference: Magic and the Supernatural, 15 - 17 March 2010, Salzburg, Austria. This version is available at http://eprints.hud.ac.uk/id/eprint/7792/ The University Repository is a digital collection of the research output of the University, available on Open Access. Copyright and Moral Rights for the items on this site are retained by the individual author and/or other copyright owners. Users may access full items free of charge; copies of full text items generally can be reproduced, displayed or performed and given to third parties in any format or medium for personal research or study, educational or not-for-profit purposes without prior permission or charge, provided: • The authors, title and full bibliographic details is credited in any copy; • A hyperlink and/or URL is included for the original metadata page; and • The content is not changed in any way. For more information, including our policy and submission procedure, please contact the Repository Team at: [email protected]. http://eprints.hud.ac.uk/ The Maids, Mother and “The Other One” of the Discworld: Exploring the magical aspect of Granny Weatherwax, Nanny Ogg, Magrat Garlick, and Agnes Nitt. Jacquelyn Bent and Helen Gavin Abstract Fantasy novelist Terry Pratchett’s Discworld is inhabited by a very diverse group of characters ranging from Death and his horse Binky, Cut-Me- Own-Throat-Dibbler, purveyor of the ‘pork pie’, the Wizard faculty of the Unseen University and an unofficial ‘coven’ of three witches. -

Models of Time Travel

MODELS OF TIME TRAVEL A COMPARATIVE STUDY USING FILMS Guy Roland Micklethwait A thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy of The Australian National University July 2012 National Centre for the Public Awareness of Science ANU College of Physical and Mathematical Sciences APPENDIX I: FILMS REVIEWED Each of the following film reviews has been reduced to two pages. The first page of each of each review is objective; it includes factual information about the film and a synopsis not of the plot, but of how temporal phenomena were treated in the plot. The second page of the review is subjective; it includes the genre where I placed the film, my general comments and then a brief discussion about which model of time I felt was being used and why. It finishes with a diagrammatic representation of the timeline used in the film. Note that if a film has only one diagram, it is because the different journeys are using the same model of time in the same way. Sometimes several journeys are made. The present moment on any timeline is always taken at the start point of the first time travel journey, which is placed at the origin of the graph. The blue lines with arrows show where the time traveller’s trip began and ended. They can also be used to show how information is transmitted from one point on the timeline to another. When choosing a model of time for a particular film, I am not looking at what happened in the plot, but rather the type of timeline used in the film to describe the possible outcomes, as opposed to what happened. -

Visual Representations of Terry Pratchett's Discworld in Time And

IMAGINATIONS: JOURNAL OF CROSS-CULTURAL IMAGE STUDIES | REVUE D’ÉTUDES INTERCULTURELLES DE L’IMAGE Publication details, including open access policy and instructions for contributors: http://imaginations.glendon.yorku.ca Visibility and Translation Guest Editor: Angela Kölling December 31, 2020 Image Credit: Cia Rinne, Das Erhabene (2011) To cite this article: Sohár, Anikó. “Each to Their Own: Visual Representations of Terry Pratchett’s Discworld in Time and Space.” Imaginations: Journal of Cross-Cultural Image Studies, vol. 11, no. 3, Dec. 2020, pp. 123-163, doi: 10.17742/IMAGE.VT.11.3.6. To link to this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.17742/IMAGE.VT.11.3.6 The copyright for each article belongs to the author and has been published in this journal under a Creative Commons 4.0 International Attribution NonCommercial NoDerivatives license that allows others to share for non-commercial purposes the work with an acknowledgement of the work’s authorship and initial publication in this journal. The content of this article represents the author’s original work and any third-party content, either image or text, has been included under the Fair Dealing exception in the Canadian Copyright Act, or the author has provided the required publication permissions. Certain works referenced herein may be separately licensed, or the author has exercised their right to fair dealing under the Canadian Copyright Act. EACH TO THEIR OWN: VISUAL REPRESENTATIONS OF TERRY PRATCHETT’S DISCWORLD IN TIME AND SPACE ANIKÓ SOHÁR When a book is translated, publishers Lorsqu’un livre est traduit, les éditeurs mo- will often modify or completely change difient souvent, voire changent complète- the cover design. -

Hogfather: a Novel of Discworld by Terry Pratchett

Hogfather: A Novel of Discworld by Terry Pratchett Ebook Hogfather: A Novel of Discworld currently available for review only, if you need complete ebook Hogfather: A Novel of Discworld please fill out registration form to access in our databases Download book here >> Series: Discworld (Book 20) Mass Market Paperback: 416 pages Publisher: Harper; Reissue edition (January 28, 2014) Language: English ISBN-10: 006227628X ISBN-13: 978-0062276285 Product Dimensions:4.2 x 0.9 x 7.5 inches ISBN10 ISBN13 Download here >> Description: Who would want to harm Discworlds most beloved icon? Very few things are held sacred in this twisted, corrupt, heartless—and oddly familiar— universe, but the Hogfather is one of them. Yet here it is, Hogswatchnight, that most joyous and acquisitive of times, and the jolly, old, red-suited gift-giver has vanished without a trace. And theres something shady going on involving an uncommonly psychotic member of the Assassins Guild and certain representatives of Ankh-Morporks rather extensive criminal element. Suddenly Discworlds entire myth system is unraveling at an alarming rate. Drastic measures must be taken, which is why Death himself is taking up the reins of the fat mans vacated sleigh . which, in turn, has Deaths level-headed granddaughter, Susan, racing to unravel the nasty, humbuggian mess before the holiday season goes straight to hell and takes everyone along with it. Terry Pratchett was brilliant and the master of a fantasy sub-genre that probably belongs to him alone. Mort is a novel set in Discworld. The Discworld novels fall into different categories: Tiffany Aching, Rincewind, the three witches, Sam Vines and the guards, and Death. -

Sfrareview in This Issue 312 Spring 2015

312 Spring 2015 Editor Chris Pak SFRA University of Lancaster, Bailrigg, Lan- A publicationRe of the Scienceview Fiction Research Association caster LA1 4YW. [email protected] Managing Editor In this issue Lars Schmeink Universität Hamburg, Institut für Anglis- SFRA Review Business tik und Amerikanistik, Von Melle Park 6 Gearing Up ............................................................................................................2 20146 Hamburg. W. [email protected] SFRA Business Nonfiction Editor #SFRA2015 ............................................................................................................2 Dominick Grace Live Long and Prosper .........................................................................................3 Brescia University College, 1285 Western Sideways in Time [conference report] ..............................................................3 Rd, London ON, N6G 3R4, Canada phone: 519-432-8353 ext. 28244. BSLS: British Society for Literature and Science [conference report] ..........5 [email protected] Feature 101 Assistant Nonfiction Editor Teaching Science Fiction .....................................................................................7 Kevin Pinkham College of Arts and Sciences, Nyack To Bottom Out: An Incomplete Guide to the New Venezuelan SF ............14 College, 1 South Boulevard, Nyack, NY 10960, phone: 845-675-4526845-675- 4526. Nonfiction Reviews [email protected] The American Shore: Meditations on a Tale of Science Fiction by Thomas M. Disch -

Terry Pratchett's Discworld.” Mythlore: a Journal of J.R.R

Háskóli Íslands School of Humanities Department of English Terry Pratchett’s Discworld The Evolution of Witches and the Use of Stereotypes and Parody in Wyrd Sisters and Witches Abroad B.A. Essay Claudia Schultz Kt.: 310395-3829 Supervisor: Valgerður Guðrún Bjarkadóttir May 2020 Abstract This thesis explores Terry Pratchett’s use of parody and stereotypes in his witches’ series of the Discworld novels. It elaborates on common clichés in literature regarding the figure of the witch. Furthermore, the recent shift in the stereotypical portrayal from a maleficent being to an independent, feminist woman is addressed. Thereby Pratchett’s witches are characterized as well as compared to the Triple Goddess, meaning Maiden, Mother and Crone. Additionally, it is examined in which way Pratchett adheres to stereotypes such as for instance of the Crone as well as the reasons for this adherence. The second part of this paper explores Pratchett’s utilization of different works to create both Wyrd Sisters and Witches Abroad. One of the assessed parodies are the fairy tales of the Brothers Grimm as well as the effect of this parody. In Wyrd Sisters the presence of Grimm’s fairy tales is linked predominantly to Pratchett’s portrayal of his wicked witches. Whereas the parody of “Cinderella” and the fairy tale’s trope is central to Witches Abroad. Additionally, to the Brothers Grimm’s fairy tales, Pratchett’s parody of Shakespeare’s plays is central to the paper. The focus is hereby on the tragedies of Hamlet and Macbeth, which are imitated by the witches’ novels. While Witches Abroad can solely be linked to Shakespeare due to the main protagonists, Wyrd Sisters incorporates both of the aforementioned Shakespeare plays. -

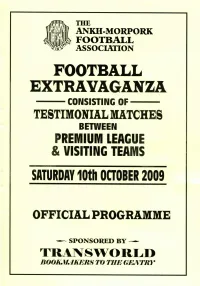

Event Programme

THE ANKH-MORPORK FOOTBAJLL ASSOCIATION FOOTBALL EXTRAVAGANZA CONSISTING OF TESTIMONIAL MATCHES BETWEEN PREMIUM LEAGUE & VISITING TEAMS SATURDAY 10th OaOBER 2009 OFFICIAL PROGRAMME ^ SPONSORED BY TRAJVSWORLD BOOKAMKEltS TO THE GEJVTRY THE ANKH-MORPORK TIME TABLE FOOTBALL SATURDAY 10th Subject to any alteration, at any time. ASSOCIATION ASSEMBLE IN OaOBER 2009 THE SPORTS GROUND FROM 11AM At about NOON A WELCOME ADDRESS BY THE MANAGEMENT & TRAINERS OF TRANSWORLD PUBLISHERS, WHO ARE TODAY'S HOSTS. ' A day that Teams will ussemble and he checked by Officials of the will go down in A-M F^\.for weapons, foodstuffs, bottles, or other Football History, impediment to fair play. i A day that when in your Note: dotage; or next week, No Linesmen or Referee us to be offered any bribe or whenever is sooner, you inducement to influence the performance of their duties in ean show your sears and a fair ami impartial manner. say "1 was there," "I ate the pies, I turned TEAMS WILL ASSEMBLE up, paid up and played FOR THE ORGANISERS TO ALLOCATE BY the game". A DRAW BETWEEN ALL TEAMS PRESENT, From all over the eountry and beyond, young men PITCH NUMBER AND KICK-OFF TIMES and women answered the call. Joined the eolours, ROUND 1. and made for one day a THE MATCHES WILL sleepy town in Somerset the huh of football KICK-OFF prowess. They came because a man ROUND 2. wrote a book. They came THE WINNING TE^VMS (SURATVORS) because his publishers* WILL THEN PLAY offered free beer. They came to make history. ROUND 3 That man was, SIR TERRY PR.\TCHETT THE FINAL And the book was, THERE WILL BE A CUP. -

Issue 6 2010.Indb

Editorial Nick Johnson & Jason Hubbard 3 Skirmish Painting Competition Results 4 Painting Competition 6 Stage Magician Prestige Class Dave Barker 7 Wizard Illustration Ricardo Guimaraes 11 Tuk Tuk Will Kirkby 12 Iron, Steam & Really Short People Part 2 Nick Johnson 14 Meet the Mages of Middle Earth David Kay 23 The Death of Magic Richard Tinsley 25 Homecoming Taylor Holloway 28 Didn’t We Have a Lovely time the Day We William Ford 34 Went to Sheffield A Drink with Nick Kyme Peter Allison 36 Artist Showcase Diego de Almeida 39 Euro Militaire 2010 Jason Hubbard 44 Sheffield Kotei 2010 Jim Freeman 46 A Gaming Group’s Adventure GD USA Mike Schaeffer 50 Games Day UK Jason Hubbard 54 The Application of Paint David Heathfield 56 Flora Basing Brett Johnson & Rebecca Hubbard 64 Sculpting Robes in Greenstuff Richard Sweet 66 A Step by Step; Nanny Ogg Mike Dodds 68 Gradients Rebecca Hubbard 72 Discworld miniature Review Various 75 Hearts & Minds: Flying Lead Supplement Dave Barker 80 Britanan Grenadiers & Troopers Peter Scholey 81 Hammer’s Slammers Dave Barker 82 Fields of Glory: Renaissance Nick Slonskyj 83 28mm Sandbag Emplacement Peter Scholey 85 Cornelius the Wizard Rebecca Hubbard 86 WW2 German Infantry Jason Hubbard 87 2 Editors Jason Hubbard Nick Johnson Layout Jason Hubbard Jason: Well folks, it seems it’s that time again - another issue of Irregular Magazine is on the virtual shelf, and what a jam-packed issue we have for you all. We have an- Proof Reader other another supplement, though I let Nick discuss that particular goody, as he was Nick Johnson involved in the writing of it. -

The Virtue of the Stereotypical Antagonist in Terry Pratchett's

BY THE STRENGTH OF THEIR ENEMIES: THE VIRTUE OF THE STEREOTYPICAL ANTAGONIST IN TERRY PRATCHETT’S ‘WITCHES’ NOVELS BY CATHERINE M. D. JOULE A thesis submitted to the Victoria University of Wellington in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Victoria University of Wellington (2021) 1 2 Abstract The comic fantasy Discworld novels of Terry Pratchett (1948-2015) are marked by their clear and insightful approaches to complex ethical issues. This has been noted in academic approaches from the beginning, with Farah Mendlesohn’s chapter “Faith and Ethics” appearing in the early collection Terry Pratchett: Guilty of Literature (2000) and many others since touching on the issues Pratchett raises. However, this thesis’s investigation into the use of stereotypes in characterisation and development of the antagonist figures within the Discworld novels breaks new ground in mapping the course of Pratchett’s approaches across six Discworld novels. This argument will focus on the ‘Witches’ sequence of novels: Equal Rites (1987), Wyrd Sisters (1988), Witches Abroad (1991), Lords and Ladies (1992), Maskerade (1995), and Carpe Jugulum (1998). Unlike other sequences in the Discworld series, these novels have a strong metatextual focus on the structural components of narrative. In this context, stereotypes facilitate both the humour and the moral arguments of these novels. Signifiers of stereotypes invoke expectations which are as often thwarted as they are fulfilled and, while resulting in humour, this process also reflects on the place of the individual within the community, the nature of right and wrong, and how we as people control the narratives which define our lives and ourselves. -

Tiffany Aching, Hermione Granger, and Gendered Magic in Discworld and Potterworld

Volume 27 Number 3 Article 16 4-15-2009 The Education of a Witch: Tiffany Aching, Hermione Granger, and Gendered Magic in Discworld and Potterworld Janet Brennan Croft University of Oklahoma Follow this and additional works at: https://dc.swosu.edu/mythlore Part of the Children's and Young Adult Literature Commons Recommended Citation Croft, Janet Brennan (2009) "The Education of a Witch: Tiffany Aching, Hermione Granger, and Gendered Magic in Discworld and Potterworld," Mythlore: A Journal of J.R.R. Tolkien, C.S. Lewis, Charles Williams, and Mythopoeic Literature: Vol. 27 : No. 3 , Article 16. Available at: https://dc.swosu.edu/mythlore/vol27/iss3/16 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Mythopoeic Society at SWOSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Mythlore: A Journal of J.R.R. Tolkien, C.S. Lewis, Charles Williams, and Mythopoeic Literature by an authorized editor of SWOSU Digital Commons. An ADA compliant document is available upon request. For more information, please contact [email protected]. To join the Mythopoeic Society go to: http://www.mythsoc.org/join.htm Mythcon 51: A VIRTUAL “HALFLING” MYTHCON July 31 - August 1, 2021 (Saturday and Sunday) http://www.mythsoc.org/mythcon/mythcon-51.htm Mythcon 52: The Mythic, the Fantastic, and the Alien Albuquerque, New Mexico; July 29 - August 1, 2022 http://www.mythsoc.org/mythcon/mythcon-52.htm Abstract Explores the depiction of gender in education, and how gender issues in education relate to power and agency, in two current young adult fantasy series featuring feisty heroines determined to learn all that they can: Hermione Granger in J.K. -

The Annotated Pratchett File, V9.0

The Annotated Pratchett File, v9.0 Collected and edited by: Leo Breebaart <[email protected]> Assistant Editor: Mike Kew <[email protected]> Organisation: Unseen University Newsgroups: alt.fan.pratchett,alt.books.pratchett Archive name: apf–9.0.5 Last modified: 2 February 2008 Version number: 9.0.5 (The Pointless Albatross Release) The Annotated Pratchett File 2 CONTENTS 1 Preface to v9.0 5 The Last Hero . 135 The Amazing Maurice and his Educated Rodents . 137 2 Introduction 7 Night Watch . 138 3 Discworld Annotations 9 The Wee Free Men . 140 The Colour of Magic . 9 Monstrous Regiment . 143 The Light Fantastic . 14 A Hat Full of Sky . 147 Equal Rites . 17 Once More, With Footnotes . 148 Mort . 19 Going Postal . 148 Sourcery . 22 Thud . 148 Wyrd Sisters . 26 Where’s My Cow? . 148 Pyramids . 31 Wintersmith . 148 Guards! Guards! . 37 Making Money . 148 Eric . 40 I Shall Wear Midnight . 149 Moving Pictures . 43 Unseen Academicals . 149 Reaper Man . 47 Scouting for Trolls . 149 Witches Abroad . 53 Raising Taxes . 149 Small Gods . 58 The Discworld Companion . 149 Lords and Ladies . 65 The Science of Discworld . 150 Men at Arms . 72 The Science of Discworld II: the Globe . 151 Soul Music . 80 The Science of Discworld III: Darwin’s Watch . 151 Interesting Times . 90 The Streets of Ankh-Morpork . 151 Maskerade . 93 The Discworld Mapp . 151 Feet of Clay . 95 A Tourist Guide to Lancre . 151 Hogfather . 103 Death’s Domain . 152 Jingo . 110 4 Other Annotations 153 The Last Continent . 116 Good Omens . 153 Carpe Jugulum . 123 Strata . 160 The Fifth Elephant . -

The Discworld Novels of Terry Pratchett by Stacie L. Hanes

Aspects ofHumanity: The Discworld Novels ofTerry Pratchett by Stacie L. Hanes Submitted in Partial Fulfillment ofthe Requirements for the Degree of Master ofArts in the English Program YOUNGSTOWN STATE UNIVERSITY May, 2004 Aspects ofHumanity: The Discworld Novels ofTerry Pratchett Stacie L. Hanes I hereby release this thesis to the public. I understand this thesis will be made available from the OhioLINK ETD Center and the Maag Library Circulation Desk for public access. I also authorize the University or other individuals to make copies ofthis thesis as needed for scholarly research. Signature: StacieaLL. Hanes, Student Approvals: Date ~ ~ /I /? ,1 ..,-...ff&?7/P;? ?~ ~C~4.~>r ,ClyYL47: Dr. Thomas Copelan ,Committee Member Date 111 Abstract Novelist Terry Pratchett is one ofEngland's most popular living writers; he is recognized, by virtue ofhis Discworld novels, as one ofthe leading satirists working today. Despite this high praise, however, Pratchett receives relatively little critical attention. His work is fantasy and is often marginalized by academics-just like the rest ofthe geme. Pratchett has a tremendous following in England and a smaller but completely devoted fan base in the United States, not to mention enough readers all over the world to justify translation ofhis work into nearly thirty languages; yet, his popularity has not necessarily resulted in the respect that his writing deserves. However, there is considerable support for Pratchett's place in the literary canon, based on his use ofsatire and parody to treat major issues. 1 Aspects of Humanity: The Discworld Novels of Terry Pratchett Introduction Novelist Terry Pratchett is one ofEngland's most popular living writers; he is recognized, by virtue ofhis Discworld novels, as one ofthe leading satirists working today.