Player Agents and Conflicts of Interest

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

CONTENTS Book 2 Coach Talk Graham Murray - Sydney Roosters Head Coach 2001 21

RLCMRLCMRLCM Endorsed By Visit www.rlcm.com.au RUGBY LEAGUE COACHING MANUALS CONTENTS Book 2 Coach Talk Graham Murray - Sydney Roosters Head Coach 2001 21 5 The Need for Innovation & Creativity in Rugby League Source of information - Queensland Rugby League Coaching Camp, Gatton 2001 Level 2 Lectures By Dennis Ward & Don Oxenham Written by Robert Rachow 9 Finding The Edge Steve Anderson - Leeds Performance Director Written by David Haynes 11 Some Basic Principles in Defence and Attack By Shane McNally - Northern Territory Institute of Sport Coaching Director 14 The Roosters Recruitment Drive Brian Canavan - Sydney Roosters Football Manager Written By David Haynes 16 Session Guides By Bob Woods - ARL Level 2 Coach 22 Rugby League’s Battle for Great Britain By Rudi Meir - Senior Lecturer in Human Movements Southern Cross University 27 Injury Statistics By Doug King RCpN, Dip Ng, L3 NZRL Trainer, SMNZ Sports Medic 33 Play The Ball Drills www.rlcm.com.au Page 1 Coach Talk GRAHAM MURRAY - Head Coach Sydney Roosters RLFC Graham Murray is widely recognised within Rugby League circles as a team builder, with the inherent ability to draw the best out of his player’s week in and week out. Murray has achieved success at all levels of coaching. He led Penrith to a Reserve Grade Premiership in 1987; took Illawarra to a major semi-final and Tooheys Challenge Cup victory in 1992; coached the Hunter Mariners to an unlikely World Club Challenge final berth in 1997; was the brains behind Leeds’ English Super League triumph in 1999; and more recently oversaw the Sydney Roosters go within a whisker of notching their first premiership in 25 years. -

TE AWAMUTU COURIER, THURSDAY, MAY 23, 2013 LETTERS to the EDITOR Te Awamutu Courier St Peter’S Pool Offers Chance to Save Money

Te Awamutu Rosetown Family Funerals 262 Ohaupo Road, Te Awamutu SSiSincere andd professionalfi l servicei when it matters most CourierPublished Tuesday & Thursday THURSDAY, MAY 23, 2013 PH 07 870 2137 www.rosetownfunerals.comwwww rosetownffunerals com YOUR COMMUNITY NEWSPAPER FOR OVER 100 YEARS CIRCULATED FREE TO 12,109 HOMES THROUGHOUT TE AWAMUTU AND SURROUNDING DISTRICTS. EXTRA COPIES 40c. BRIEFLY Maungatautari Island Legal drugs If you want to learn more about the risks associated with legal highs, keep next Wednesday evening free. A number of groups are presenting information to the wins Supreme Award community about legal synthetic drugs that are Maungatautari Ecological readily available. The Island Trust has won the awareness night is at Te Supreme Award at the 2013 Awamutu College Hall from TrustPower Waipa District 7pm. Community Awards. There will be more in-depth The awards were announced information in Tuesday’s and presented Monday night at edition of the Te Awamutu a function at the Cambridge Courier. Town Hall. For winning the Supreme Encore Award, Maungatautari Ecologi- After a successful concert cal Island Trust received a in Te Awamutu several weeks framed certificate, a trophy and ago, Luke Thompson and $1500 prize money. Lydia Cole, together with Phil Maungatautari Ecological Van der wel, are back to Island Trust now has the oppor- entertain. tunity to represent the district They will be at the Walton at the 2013 TrustPower National Street cafe on Friday May 24 Community Awards, which are being held in Invercargill and at 7:30pm. For more details Southland region in March see facebook.com/WaltonSt. -

Fiji & New Zealand

T O U R O F FIJI & NEW ZEALAND 19 September – 7 October 2012 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS There are many organizations the Australian Schools Union wishes to thank for their assistance in helping with the Tour: The Australian Schools Rugby Union wishes to thank its Major Sponsors: – a major sponsor of the AUSTRALIAN SCHOOLS RUGBY UNION We also receive assistance from the following very good friends: presenters of BRONZE BOOT AWARD Test Match Australian v New Zealand Proudly supporting Australian Schools Rugby since 1997 Men’s clothing in Sydney has had a home at Barclays for over 60 years. We have provided quality, timeless and affordable men’s clothing to several generations of men. We are now pleased to announce the launch of our online store www.barclays.net.au. To celebrate 15 years of support, Barclays Online will donate 5% of your purchase to your school. When purchasing at Barclays online, please leave the name of your school in the comment box and 5% of your sale will be donated in your name. Browsing or buying online, you can be assured of our long-term reputation for providing consistency to all our valued customers. www.barclays.net.au 2012 ASRU EXECUTIVE AND COMMITTEE OFFICE BEARERS Patron: Ron Graham Welcome President: Br R J (Bob) Wallace AM Vice President: Damien Barker from the President ASRU Hon Secretary: J Rae Hon Treasurer/Administrator: A D Elliot Executive Members: THE Lions tour to Australia next year is being J Brew, G Cronan, K Culliver & P Langtry described favourably as a return to the good old Committee Members: days of touring. -

25 November 2008 RE: Media Summary Saturday 15 No

TO: NZRL Staff, Districts and Affiliates and Board FROM: Cushla Dawson DATE: 25 November 2008 RE: Media Summary Saturday 15 November to Tuesday 25 November 2008 Kiwis are content to polish the silverware: KEEP your opinions to yourselves and we will keep the World Cup. The message from across the ditch was yesterday loud and clear following revelations Ricky Stuart will be investigated for verbally abusing referee Ashley Klein the morning after the Kangaroos' disastrous defeat. New Zealand Rugby League general manager Peter Cordtz said New Zealanders were too busy enjoying the historic victory and the prestigious silverware to worry about the controversy whipped up in Australia or Stuart's opinions. Stuart to be investigated over abuse claims: Australian coach Ricky Stuart will be formally investigated following a complaint he abused World Cup referee Ashley Klein and a top England official after Saturday night's shock World Cup final loss to New Zealand. Rugby League International Federation chairman Colin Love confirmed the RLIF would follow-up on a complaint from England's director of referees Stuart Cummings that he and Klein were abused by Stuart in the foyer of the team's Brisbane hotel the morning after the Kiwis downed the Kangaroos 34-20. The real loss for Rugby League: I'll declare from the outset that I'm from an AFL state, Victoria. ....and while we support Melbourne Storm to the hilt, the focus here is very much on the AFL. It borders on being an obsession. But you don't have to have too much of the Rugby League smarts about you to know a bunch of sore losers when you see them. -

Daily 30 Jul 08

ISSN 1834-3058 Travel Daily AU TMS ASIA PACIFIC First with the news SATISFY YOUR CURIOSITY Wed 01 Oct 08 Page 1 EDITORS: Bruce Piper and Guy Dundas CLICK HERE! WWWAUSTRIANCOM E-mail: [email protected] Ph: 1300 799 220 QF names A380 Comp winner TODAY we announce the winner SOME lucky people in the travel Kuoni buys Aussie DMC of our Vietnam competition (p2) industry yesterday had the SWISS travel giant Kuoni has turnover of 21 million Swiss as well as a fabulous new comp opportunity to fly in the new signed a deal to acquire francs (A$23.7m). offering a trip to Macau - see p5. Qantas Airbus A380. Melbourne-based destination “Australian Tours Management The packed plane departed management company Australian ideally complements our Sydney for a short flight north, Tours Management (ATM). activities in Asia,” said Rolf over the Hunter Valley, allowing ATM was founded in 1983 and is Schafroth, Kuoni head of Strategic those on board to try out the new partly owned by Bee Ho Teow, Business Division Destinations. in-flight product for themselves. who sold the TravelSpirit group “We see significant growth The trip followed the official (Explore Holidays) to Flight potential in Australia in the naming ceremony of the plane, in Centre last year for $10m. medium term, especially for honour of Australian aviation Teow is well known across the travellers from Asian countries,” pioneer Nancy-Bird Walton. Australian tourism industry, and is he added. “Nancy-Bird’s courage, resilience currently on the board of Tourism Kuoni’s head office is in Zurich and optimisim represent the very Victoria. -

Wavelength-2016-T3

THE MAGAZINE OF WAVERLEY COLLEGE ISSUE 23 NUMBER 1 @ WINTER 2016 < 6 Take a Bow, High School Musical! May Procession < 8 Visual Arts & Peter Frost TAS Exhibition 50 Years of Cadet Unit > 10 > 15 ISSUE 23 VOLUME 1 NOTE FROM THE EDITOR WINTER 2016 PRINT POST 100002026 This edition marks significant changes at Waverley: Head of College, Ray Paxton has announced he will depart at the end of 2016; we introduce a new Deputy Head of College, Graham Leddie, who hails from Nudgee; PUBLISHER and we also welcome our new Development Manager, Rebecca Curran. We also celebrate two outstanding Waverley College creative arts events from our students; we mark the Jubilee of ex-Headmaster, Br Bob Wallace at our May 131 Birrell Street, Procession; and we sadly note the death of another ex-Headmaster, Br Kevin Kirwan. Read on... Waverley NSW 2024 Jennifer Divall TELEPHONE 02 9369 0600 EMAIL IN THIS ISSUE [email protected] WEB 3 FROM THE HEADMASTER 15 OBU PRESIDENT’S REPORT waverley.nsw.edu.au The Start of a New Era Waverley College Old Boys’ Union 4 ASKING THE RIGHT QUESTIONS Peter Frost 50 Years of Cadet Unit EDITOR Letter from the Edmund Rice Education 16 OBU EXECUTIVE PROFILES Jennifer Divall Australia’s Executive Director, Dr Wayne Tinsey Marketing Manager OBU Council Sets up Sub-committees 5 DEPUTY HEADMASTER Retirement from the Old Boys’ Council ALUMNI RELATIONS Introducing Mr Graham Leddie 17 OBU NEWS Rebecca Curran 6 Take a bow, High School Musical! TELEPHONE Australia Day Honours 02 9369 0753 8 106TH ANNUAL MAY PROCESSION Legal Award EMAIL -

Foundation Licensed Under Cover Driving Range Bar • Functions

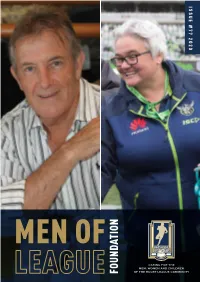

ISSUE #77 2020 MEN OF CARING FOR THE MEN, WOMEN AND CHILDREN OF THE RUGBY LEAGUE COMMUNITY FOUNDATION LICENSED UNDER COVER DRIVING RANGE BAR • FUNCTIONS Aces Sporting Club • Springvale Rd & Hutton Rd, Keysborough Ph. 9701 5000 • acessportingclub.com.au • /AcesSportingClub LOOK FORWARD TO REOPENING SOON ✃ PRPREESENTSENT THISTHIS FFLLYEYERR ININ THE THE DRIVING DRIVING RANGE RANGE FOR FOR 200200 BBAALLLLSS FFOORR $$1100 SPOSPORRTTIINGNG CCLULUBB Can not be used in conjunction with any other offer. Terms and Conditions Apply. IN THIS FROM THE OUR COVER Introducing our newest board member Katrina Fanning and recently announced life member Tony Durkin. PROFESSOR THE INSIDE THIS ISSUE 5 McCloy Group corporate membership HONOURABLE 6 Tony Durkin 8 Lionel Morgan STEPHEN MARTIN 11 Katrina Fanning 14 Socially connecting As you read this message, the Foundation brings enormous experience to our board 16 Try July is still unfortunately greatly impacted by as a former Jillaroo, having played 26 Tests 17 Arthur Summons COVID-19 and the necessary restrictions that for Australia and held the roles of president 18 Keith Gee have been imposed by health and government of the Australian Women’s Rugby League 21 Mortimer Wines promotion authorities. Association, chairperson of the Australian 22 Noel Kelly Rugby League Indigenous Council and a 24 Champion Broncos 20 years on The Foundation itself remains in hibernation director of the board of the Canberra Raiders. 26 Ranji Joass mode. Most staff remain stood down, and Welcome Katrina! 34 Phillippa Wade and her Storm Sons we are fortunate that JobKeeper has been 28 Q/A with Peter Mortimer available to us. -

España Campeón Y Subcampeón En El Mundial Universitario De ‘Seven’ De Córdoba

Boletín informativo de la Federación Española de Rugby Temporada 2007/2008. 20 de julio de 2008 Rugby. Campeonato del Mundo de Rugby Universitario España Campeón y Subcampeón en el Mundial Universitario de ‘Seven’ de Córdoba España ha salido por la puerta Después, ya en las semifinales, grupo. Más tarde se enfrentarían grande en el Mundial tuvieron un complicadísimo duelo en la final. Universitario celebrado en la con la selección de Francia. La En los cuartos de final, España se ciudad andaluza de Córdoba; con victoria se logró gracias a un enfrentó al cuarto clasificado del el título para el equipo femenino y sensacional ensayo, esquivando grupo B, Italia. El equipo nacional el sucampeonato para el a todas las rivales desde el medio vencía a la selección de Italia sin masculino. campo hasta la zona de ensayo, ceder ni un solo punto, 12-0. En España ha tenido una magnífica de Barbará Pla, que ella misma se las semifinales le esperaba actuación en el Mundial encargó de transformar. De esta Francia y el equipo galo presentó Universitario celebrado en forma daba la clasificación para mucha batalla a los chicos Córdoba desde el pasado jueves la final al equipo español. En la dirigidos por el ‘Tiki’ Inchausti y hasta hoy sábado. En la final final les esperaba Canadá y, en por Enrique Roldán. El resultado disputada a las 19:00 horas la otro vibrante partido, el ‘Siete’ final fue de 17-12, con ensayos de selección femenina se imponía a español se proclamaba Campeón david Montoliú y, en los instantes Canadá por 17-12. -

Wavelength Issue 22 Summer1.Pdf

THE MAGAZINE OF WAVERLEY COLLEGE ISSUE 22 NUMBER 2 @ SUMMER 2015 < 9 Archbishop European visits Waverley Concert Tour College 4 Restoration of Historic Portraits < 6 Junior School Where are they now? Focus > 10 USA & Canada < 29 ISSUE 22 VOLUME 2 NOTE FROM THE EDITOR SUMMER 2015 PRINT POST 100002026 Waverley alumni are everywhere (that matters). Don’t miss our special feature in this edition on old boys living and working in the USA. A reminder to please dig deep to support the Capital Appeal, if you can: PUBLISHER It’s providing a much-needed indoor venue to accommodate the entire school, as well as new gym, Waverley College technology and hospitality facilities. In doing so, you’ll help the college keep meeting the challenge of 131 Birrell Street, providing great educational opportunities at sensible fees. Enjoy this edition and please keep in touch. Waverley NSW 2024 Jennifer Divall TELEPHONE 02 9369 0600 EMAIL [email protected] IN THIS ISSUE WEB 3 FROM THE HEADMASTER 21 OBU PRESIDENT’S REPORT waverley.nsw.edu.au Designing the Future Waverley College Old Boys’ Union EDITOR 4 105TH ANNUAL MAY PROCESSION 22 REUNIONS Jennifer Divall AND FEAST OF EDMUND RICE First Annual ‘Muster’ Augurs Well for the Future Archbishop’s 1st Visit to Waverley Marketing Manager Class of 2000 15 Year Reunion 5 Farewell Tony Galletta ALUMNI RELATIONS Magazines from 1931 to 1988 now online & DEVELOPMENT New Deputy Announced 23 OBU NEWS Robyn Moore 6 POSTCARDS FROM THE PAST A Piece of Football History Alumni Relations Restoration of Historic Portraits -

The Magazine of Waverley College Issue 20 Number 1 @ Winter 2013

THE MAGAZINE OF WAVERLEY COLLEGE ISSUE 20 NUMBER 1 @ WINTER 2013 World Premiere at 11 AFL Kicks Off College Festival at Waverley < 9 Opening the Learning the ropes doors to future at Cadet camp students 14 > 16 > 4 OLM Community closes Full contents after 110 Years see page 2 ISSUE 20 VOLUME 1 elcome to the new edition of Wavelength achievements of our ex students and their families. WINTER 2013 Magazine, a publication which creates an Your contributions are very welcome. PRINT POST PP349181/01591 important connection between Waverley I would like to take this opportunity to recognise College and our wider community of Old the many years of wonderful work done by the PUBLISHER Boys, families and friends. To keep you magazine’s previous editor and designer, Old Boy of Waverley College Winformed, we have expanded the magazine and 1962, Mr Col Blake. The hours of personal time he 131 Birrell Street, given it a bright new look that we hope you will has dedicated to the task over the years cannot be Waverley NSW 2024 enjoy and find readable. Alumni news will be an underestimated. Of course, Col continues to be important part of the new Wavelength, so I closely involved with Wavelength in his role as Vice TELEPHONE encourage you to forward to us any news you may President of the Waverley College Old Boys Union. 02 9369 0600 have about reunions, major life events or Jennifer Divall EMAIL [email protected] WEB waverley.nsw.edu.au IN THIS ISSUE 3 FROM THE HEADMASTER 21 OLD BOYS UNION EDITORIAL TEAM In Pursuit of Excellence President’s -

The Decade in Review the Wallabies 2000-2009

THE DECADE IN REVIEW THE WALLABIES 2000-2009 www.GreenAndGoldRugby.com THE DECADE IN REVIEW – THE WALLABIES 2000‐2009 Established in 2007, GreenAndGoldRugby (G&GR) is Australia’s premier rugby blog and forum. From its inception, G&GR’s aim has been to provide a place for those interested in any facet of Australian rugby to come together to share opinions, knowledge and their passion for the sport. It is a non‐profit, independent venture run on the love of the game. For content and tone, our guiding principle has always been “what would we want to read, watch, listen to or talk about?” This has led to a unique blend of opinion, analysis, humour and other forms of interactive multimedia, such as live match reports and videos – all delivered in a no‐nonsense and sometimes irreverent manner, just as you’d find between mates in a rugby club. This site is for rugby fans and we always aim to take a different slant on how we look at the sport we love and what we like to do is try to talk rugby without the bullshit. G&GR readers will have noticed the tremendous level of input and comment from Noddy both a Forum participant and as one of the Blog contributors. However, to end the decade Noddy has really stepped up another level by putting together what must surely be the most comprehensive Wallabies review in the modern era. During December there’s been coverage of everything from the Games of the Decade, the Tries of the Decade and the Wallaby XV of the decade appearing on the G&GR site. -

V NSW Waratahs

Force Waratahs Pek Cowan 1 Benn Robinson Ben Whittaker 2 Tatafu Polota-Nau Tim Fairbrother 3 Sekope Kepu Sam Wykes 4 Dean Mumm (C) Nathan Sharpe (C) 5 Kane Douglas Richard Brown 6 Ben Mowen Jono Jenkins 7 Pat McCutcheon Ben McCalman 8 Wycliff Palu v Brett Sheehan 9 Luke Burgess D Willie Ripia 10 Kurtley Beale NSW Waratahs Cameron Shephard 11 Drew Mitchell Gene Fairbanks 12 Tome Carter Saturday 9th April 2011 Nick Cummins 13 Ryan Cross nib Stadium, Perth David Smith 14 Aiteli Pakalani James O'Conner 15 Lachie Turner Kick Off: 8.05pm Reserves Nathan Charles 16 Damien Fitzpatrick Kieran Longbottom 17 Al Baxter Tom Hockings 18 Sitaleki Timani J.B. O'Reilly's Tevita Metuisela 19 Dave Dennis James Stannard 20 Chris Alcock Rory Sidey 21 Brendan McKibbin Pat Dellit 22 Daniel Halangahu Key match-ups Ben McCalman vs Wycliff Palu. These two will go hammer and tongs all night (unless Palu’s gamey knee buckles again) in an attempt to show Robbie D that their style is a better fit for the Wallabies; Aggression, mobility and work rate vs sheer brute force. We had better hope Palu has a poor game because the go forward he provides, particularly off the back of the scrum, could make the difference between the Tahs flying or floundering. Amongst the backs you can’t look past Brett Sheehan vs Luke Burgess. Sheehan will ensure that this becomes an absolute scrap out. He no doubt has a bit of an axe to grind as the arrival of Burgess has seen Sheehan pushed out of both the Waratahs starting jersey and the Wallabies squad.