Augsburg Confession VII Revisited

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Mission As Nota Ecclesiae?: Testing the Scope of Augsburg Confession 7 and 8

Is mission a sign of the church? The Rev. Dr. Klaus Detlev Schulz’s presentation from the Mission as Nota Ecclesiae?: Concordia University Irvine Joint Professors’ Conference Testing the Scope of explains. Augsburg Confession 7 and 8 by Klaus Detlev Schulz n our discussion of AC VII and AC VIII, a few the mission discussions orbited around these articles fundamental questions have to be answered if we gradually illuminated their missiological potential.2 bring systematics and missiology together, as I’m told I. Stage 1: Mission marginalized Ito do. How do the two articles in the Augsburg Confession relate to missions? How does ecclesiology inform mission The ecclesiology of the Augsburg Confession as and how does mission inform ecclesiology? Is, as my title defined in AC VII did not go unnoticed by mission schol- indicates, mission a sign of the church? Here we touch on ars. For example, in an essay, Theological Education in a sensitive topic. In terms of becoming Missionary Perspective, David Bosch involved in mission both theologically Mission is not takes a stab at the Protestant defini- tions of the church, of which AC VII and in practice, Lutheranism is a the possession of Johnny-come-lately. It took time to was the first: develop a missiology that would clarify a few committed Another factor responsible for the issues related to foreign missions. Of Christians more present embarrassment in the field course, as rightly pointed out, Luther’s pious than others of mission is that the modern mis- theology and Lutheran theology is a seed . but rather it sionary enterprise was born and 1 bed for missions, yet the seed still had belongs to the bred outside the church. -

The Word-Of-God Conflict in the Lutheran Church Missouri Synod in the 20Th Century

Luther Seminary Digital Commons @ Luther Seminary Master of Theology Theses Student Theses Spring 2018 The Word-of-God Conflict in the utherL an Church Missouri Synod in the 20th Century Donn Wilson Luther Seminary Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.luthersem.edu/mth_theses Part of the Christian Denominations and Sects Commons, and the History of Christianity Commons Recommended Citation Wilson, Donn, "The Word-of-God Conflict in the utherL an Church Missouri Synod in the 20th Century" (2018). Master of Theology Theses. 10. https://digitalcommons.luthersem.edu/mth_theses/10 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Theses at Digital Commons @ Luther Seminary. It has been accepted for inclusion in Master of Theology Theses by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Luther Seminary. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. THE WORD-OF-GOD CONFLICT IN THE LUTHERAN CHURCH MISSOURI SYNOD IN THE 20TH CENTURY by DONN WILSON A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of Luther Seminary In Partial Fulfillment, of The Requirements for the Degree of MASTER OF THEOLOGY THESIS ADVISER: DR. MARY JANE HAEMIG ST. PAUL, MINNESOTA 2018 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS Dr. Mary Jane Haemig has been very helpful in providing input on the writing of my thesis and posing critical questions. Several years ago, she guided my independent study of “Lutheran Orthodoxy 1580-1675,” which was my first introduction to this material. The two trips to Wittenberg over the January terms (2014 and 2016) and course on “Luther as Pastor” were very good introductions to Luther on-site. -

In the Lutheran Confessions: Dialogue Within the Reformation Spirit Oscar Cole-Arnal

Consensus Volume 7 | Issue 3 Article 1 7-1-1981 Concordia' and 'unitas' in the Lutheran confessions: dialogue within the Reformation spirit Oscar Cole-Arnal Follow this and additional works at: http://scholars.wlu.ca/consensus Recommended Citation Cole-Arnal, Oscar (1981) "Concordia' and 'unitas' in the Lutheran confessions: dialogue within the Reformation spirit," Consensus: Vol. 7 : Iss. 3 , Article 1. Available at: http://scholars.wlu.ca/consensus/vol7/iss3/1 This Articles is brought to you for free and open access by Scholars Commons @ Laurier. It has been accepted for inclusion in Consensus by an authorized editor of Scholars Commons @ Laurier. For more information, please contact [email protected]. “CONCORDIA” AND “UNITAS” IN THE LUTHERAN CONFESSIONS Dialogue Within the Reformation Spirit Oscar L. Arnal Within the process of determining the criteria for fellowship among Canadian Lutherans, this symposium has been assigned the specific task of analyzing the re- lationship between concordia and unitas in the Lutheran Confessions. With that end in mind, I propose a comparison of two sets of our symbolic documents, namely the Augsburg Confession and the Book and Formula of Concord. By employing such a method, it is hoped that our historical roots may be utilized in the service of our re- sponsibility to critique and affirm each other. Before one can engage in this dialogue with the past, it becomes necessary to come to terms with our own presuppositions and initial assumptions. All our asser- tions, even our historical and doctrinal convictions, are rooted within the reality of our biological and sociological environments. We speak out of experiences which are our own both individually and collectively. -

The New Translation of the Book of Concord: Closing the Barn Door After

Volume 66:2 April 2002 Table of Contents Can the ELCA Represent Lutheranism? Flirting with Rome, Geneva, Canterbury and Herrnhut Louis A. Smith .................................99 Taking Missouri's Pulse: A Quarter Century of Symposia Lawrence R. Rast Jr. ........................... 121 The New English Translation of The Book of Concord (Augsburg/Fortress2000): Locking the Barn Door After. .. Roland F. Ziegler ..............................145 Theological Observer ...............................167 Body, Soul, and Spirit Proof Text or No Text? The New Fundamentalism Book Reviews ......................................175 Icons of Evolution: Science of Myth? By JonathanWells. ..................................Paul A. Zimmerman The Task of Theology Today. Edited by Victor Pfitzner and Hilary Regan. ........... Howard Whitecotton 111 Reading the Gospel. By John S. Dunne. ............................Edward Engelbrecht Mark. By R. T.France. .................... Peter J. Scaer Pastors and the Care of Souls in Medieval England. Edited by John Shinners and William J. Dohar. ..............................Burnell F. Eckardt The Imaginative World of the Reformation. By Peter Matheson. ................. Cameron MacKenzie Scripture and Tradition: Lutherans and Catholics in Dialogue IX. Edited by Harold C. Skillrud, J. Francis Stafford, and Daniel F. Martensen. ........... Arrnin Wenz On Being a Theologian of the Cross: Reflections on Luther's Heidelberg Disputation, 1518. By Gerhard Forde. .................................. Arrnin Wenz i Received. ................................... -

\200\200The American Recension of the Augsburg Confession

The American Recension of the Augsburg Confession and its Lessons for Our Pastors Today David Jay Webber Samuel Simon Schmucker Charles Philip Krauth John Bachman William Julius Mann Wisconsin Evangelical Lutheran Synod Evangelical Lutheran Synod Arizona-California District Pastors Conference West Coast Pastors Conference October 20-22, 2015 April 13 & 15, 2016 Green Valley Lutheran Church Our Redeemer Lutheran Church Henderson, Nevada Yelm, Washington In Nomine Iesu I. Those creeds and confessions of the Christian church that are of enduring value and authority emerged in crucibles of controversy, when essential points of the Christian faith, as revealed in Scripture, were under serious attack. These symbolical documents were written at times when the need for a faithful confession of the gospel was a matter of spiritual life or death for the church and its members. For this reason those symbolical documents were thereafter used by the orthodox church as a normed norm for instructing laymen and future ministers, and for testing the doctrinal soundness of the clergy, with respect to the points of Biblical doctrine that they address. The ancient Rules of Faith of the post-apostolic church, which were used chiefly for catechetical instruction and as a baptismal creed, existed in various regional versions. The version used originally at Rome is the one that has come down to us as the Apostles’ Creed. These Rules of Faith were prepared specifically with the challenge of Gnosticism in view. As the Apostles’ Creed in particular summarizes the cardinal articles of faith regarding God and Christ, it emphasizes the truth that the only God who actually exists is the God who created the earth as well as the heavens; and the truth that God’s Son was truly conceived and born as a man, truly died, and truly rose from the grave. -

The Use of the Church Fathers in the Formula of Concord

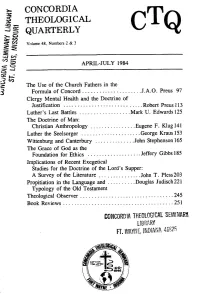

CONCORDIA THEOLOGICAL QUARTERLY Volume 48. Numbers 2 & 3 APRIL-JULY 1984 The Use of the Church Fathers in the Formula of Concord .....................J.A.O. Preus 97 Clergy Mental Health and the Doctrine of Justification ............................Robert Preus 1 13 Luther's Last Battles ..................Mark U. Edwards 125 The Doctrine of Man: Christian Anthropology ................Eugene F. Klug 14 1 Luther the Seelsorger .....................George Kraus 153 Wittenburg and Canterbury ............. .John Stephenson 165 The Grace of God as the Foundation for Ethics ....... ............Jeffery Gibbs 185 Implications of Recent Exegetical Studies for the Doctrine of the Lord's Supper: A Survey of the Literature ... ............John T. Pless 203 Propitiation in the Language and ..........Douglas Judisch 22 1 Typology of the Old Testament Theological Observer .................................245 Book Reviews .......................................251 The Use of the Church Fathers in the Formula of Concord J.A.O. Preus The use of the church fathers in the Formula of Concord reveals the attitude of the writers of the Formula to Scripture and to tradition. The citation of the church fathers by these theologians was not intended to override the great principle of Lutheranism, which was so succinctly stated in the Smalcalci Ar- ticles, "The Word of God shall establish articles of faith, and no one else, not even an angel" (11, 2.15). The writers of the Formula subscribed wholeheartedly to Luther's dictum. But it is also true that the writers of the Formula, as well as the writers of all the other Lutheran Confessions, that is, Luther and Melanchthon, did not look upon themselves as operating in a theological vacuum. -

THE VOCATION of a LUTHERAN COLLEGE in the Midst of American Higher Education

Intersections Volume 2001 | Number 12 Article 5 2001 The oV cation of a Lutheran College L. DeAne Lagerquist Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.augustana.edu/intersections Augustana Digital Commons Citation Lagerquist, L. DeAne (2001) "The ocaV tion of a Lutheran College," Intersections: Vol. 2001: No. 12, Article 5. Available at: http://digitalcommons.augustana.edu/intersections/vol2001/iss12/5 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Augustana Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Intersections by an authorized administrator of Augustana Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE VOCATION OF A LUTHERAN COLLEGE in the midst of American Higher Education L. DeAne Lagerquist My task is to examine the vocation of Lutheran colleges in higher education. Unfortunately few faculty members the midst of American higher education, to consider both come out of graduate school informed about these topics. the work to which these schools are called and the manner Our ignorance prevents a clear view either of the whole of in which that work is carried out in a way that suggests the enterpriseor of the place our schools occupy in it. My how the schools compare to other Americanschools and to plot is not the decline of authentic religious life on one another. Behind this descriptive task there lurks, campuses under the rubric of either secularization or unarticulated, a dual demand forjustification. First, show disengagement nor is it a rebuttal of such a thesis.2 Rather that the designation Lutheran is significant now, not only I intend to provide a brief chronological account that draws in the past; and second, show that it matters in ways that attention to commonality and difference among Lutheran make the schools worth maintaining and attending in the colleges and between them and other American colleges. -

Caspar Schwenckfeld's Commentary on the Augsburg Confession

Wilfrid Laurier University Scholars Commons @ Laurier Theses and Dissertations (Comprehensive) 1980 Caspar Schwenckfeld’s Commentary on the Augsburg Confession: A Translation and Critical Introduction Fred A. Grater Wilfrid Laurier University Follow this and additional works at: https://scholars.wlu.ca/etd Part of the Christianity Commons, and the History of Christianity Commons Recommended Citation Grater, Fred A., "Caspar Schwenckfeld’s Commentary on the Augsburg Confession: A Translation and Critical Introduction" (1980). Theses and Dissertations (Comprehensive). 1416. https://scholars.wlu.ca/etd/1416 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by Scholars Commons @ Laurier. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations (Comprehensive) by an authorized administrator of Scholars Commons @ Laurier. For more information, please contact [email protected]. CASPAR SCHWENCKFELD'S COMMENTARY ON THE AUGSBURG CONFESSION A TRANSLATION AND CRITICAL INTRODUCTION By Fred A. Grater B.A. Albright College, 1965 M.S. in L.S. Drexel University, 1967 THESIS Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Master of Arts degree Wilfrid Laurler University 19* 0 UMI Number: EC56338 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent on the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. JUMT_ Dissertation Publishing UMI EC56338 Copyright 2012 by ProQuest LLC. All rights reserved. This edition of the work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code. -

Augsburg Confession & Luther's Catechisms

Augsburg Confession & Luther’s Catechisms Colleagues, I’m coming to the end of the Winter Quarter in teaching 15 students about the Lutheran Confessions here in St. Louis. The course is an offering of the Lutheran School of Theology here in town, a ministry of the Metro St. Louis Coalition of ELCA congregations. For the upcoming Easter term the coalition asks for one on “Heresies Revisited.” So if you’ve got any heresies lying around–warmed over old ones or brand new ones–tell me about them. We’ve spend most of our time this quarter on three Reformation era documents of 1530-31, namely, the Augsburg Confession, the Pontifical “Confutation” [= Rebuttal] of the AC, and then Melanchthon’s response to that Confutation in his “Apology” [=Defense] of the AC. We read these three side- by-side: point, counterpoint, and counter-counterpoint. We’ll conclude the course with Luther’s 2 catechisms. Although there are 28 articles to the AC, they are not presented as a clothesline with 28 items of theological laundry hanging there–all of which are to be believed. Early on Melanchthon says that the Augsburg confessors are talking about only one doctrine. His Latin designation is “doctrina evangelii,” the doctrine [singular] that is the Gospel. All the remaining articles are nothing more than “articula”-tions of that one Good News. Thus even the ancient doctrine of the Trinity comes out, not as the “truth you should believe” about God, but a proposal for talking about God so that it comes out to be Good News. Farmboy that I am I’ve taken an old-fashioned wagon wheel as our classroom image for the structure of the AC. -

The Lutheran Tradition

The Lutheran Tradition Religious Beliefs and Healthcare Decisions Edited by Deborah Abbott Revised by Paul Nelson uring the Middle Ages, most of western Europe Dwas united, however tentatively, under the lead- ership of the Roman Catholic church. In the early sixteenth century, this union fractured, due in part to the work of a German monk named Martin Luther. Luther had striven to guarantee his salvation through ascetic practices but slowly came to believe that Contents salvation can come only through the grace of God, The Individual and the 4 not through any human effort. This fundamental Patient-Caregiver Relationship principle of Luther’s thought, “salvation by grace through faith alone,” diverged from the traditional Family, Sexuality, and Procreation 6 Roman Catholic belief that both faith and human Genetics 12 effort are necessary for salvation. The other funda- Organ and Tissue Transplantation 14 mental principle of Luther’s thought, that the Bible is the sole rule of faith and the only source of authority Mental Health 15 for doctrine, contrasts with the Roman Catholic Medical Experimentation 15 reliance on both the Bible and tradition. Luther and Research translated the Bible into German and, thanks to the Death and Dying 16 recent invention of the printing press, it was distrib- uted widely and became a best-seller. The availability Special Concerns 19 of a Bible in the language of the common people, coupled with Luther’s idea of the Bible as the sole source of authority, marked the beginning of a signifi- cant shift away from Rome as the final source of reli- gious authority for many Christians. -

Lutheran Forum Vol. 43, No. 2, Summer 2009

Free Sample Issue Special Edition LUTHERAN FORUM FREE SAMPLE IssUE SPECIAL EDITION FROM THE EDITOR HAGIOGRAPHY Still Life with Baptism St. Nenilava Sarah Hinlicky Wilson 2 James B. Vigen 27 OLD TESTAMENT GLOBAL LUTHERANISM The Trinity in Ezekiel Lars Levi Laestadius and the Nordic Revival Robert W. Jenson 7 Hannu Juntunen 34 NEW TESTAMENT BEYOND AUGSBURG The Lament of the Responsible Child Mennonites and Lutherans Re-Remembering the Past Elisabeth Ann Johnson 10 John D. Roth 39 AMERICAN LUTHERAN HISTORY DOCTRINE Exploding the Myth of the Boat The Prenatal Theology of Mark A. Granquist 13 Catharina Regina von Greiffenberg Joy Schroeder 44 LEX ORANDI LEX CREDENDI Longing for the Longest Creed PUBLIC WITNESS Robert Saler 16 Whether Lawyers and Judges, Too, Can Be Saved Humes Franklin Jr. 51 SEEDLINGS How to Revive a Dying Parish AND NOW FOR SOMETHING COMPLETELY DIFFERENT Brad Hales 19 The Book That Cost a Cow: A Lutheran Testimony (Of Sorts) HYMN Piotr J. Małysz 55 “Jesus Christ, Our Great Redeemer” Martin Luther 22 COVER A Thousand Years of Catholics, Lutherans, and STUDIES IN LUTHER Revolutionaries in Strasbourg’s Cathedral Brother Martin, Augustinian Friar Andrew L. Wilson 64 Jared Wicks, S.J. 23 Please send editorial correspondence and manuscript submissions to: [email protected]. Editor All Bible quotations from the ESV unless otherwise noted. Sarah Hinlicky Wilson Subscribe to Lutheran Forum at <www.lutheranforum.com/subscribe> Associate Editors $19 for one year, $37 for two. Or try the Forum Package with the monthly Piotr J. Małysz, Matthew Staneck Forum Letter: $28.45 for one year, $51.95 for two. -

The Formula of Concord (1576-80) and Satis Est

The Formula of Concord (1576-80) and Satis Est Nicholas Hoppmann Nicholas Hoppmann is a senior history major at Eastern Illinois University. He wrote this paper for Dr. David Smith’s undergraduate Western Civilization since the Reformation survey class in the spring of 2000. rticle VII of the Augsburg Confession (1530) has long guided Lutherans in their attempts to bring together the denominations. It defines the one holy catholic church, of which all true Christians are members, doctrinally, stating that the church is a gathering where “the Gospel is taught purely and the sacraments are administered rightly.” Article AVII’s satis est states, “it is sufficient for the true unity of the Christian church that the gospel be preached in conformity with a pure understanding of it and that the sacraments be administered in accordance with the divine word.” And yet, the Lutheran Confessions of the sixteenth century condemned the teachings of other Reformation churches as well as the Papacy. Lutherans hope that by participating in discussions with the descendants of these sixteenth- century churches, doctrinal agreements will be reached that will render the Lutheran anathemas obsolete. This process has raised many important questions about the satis est. One of the most important questions is: how do the many other doctrines presented in the Lutheran Confessions relate to the doctrine of satis est? Recently the Evangelical Lutheran Church in America (ELCA, the largest Lutheran Church body in the United States), which subscribes to the Lutheran Confessions (contained in The Book of Concord), has declared that several Calvinist Churches are orthodox.