The Urban Regeneration of the Peripheral Areas

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Cover 2 2019-Vers 2 Copia

Open Access Publishing Series in PROJECT | Essays and Researches 2 PRO-INNOVATION PROCESS PRODUCTION PRODUCT Edited by Giuseppe De Giovanni Francesca Scalisi Open Access Publishing Series in PROJECT | Essays and Researches Editor in Chief Cesare Sposito (University of Palermo) International Scientific Committee Carlo Atzeni (University of Cagliari), Mario Bisson ( Polytechnic of Milano) , Tiziana Campisi (University of Palermo), Maurizio Carta (University of Palermo), Xavier Casanovas (Polytechnic of Catalunya), Giuseppe De Giovanni (University of Palermo), Clice de Toledo Sanjar Mazzilli (University of São Paulo), Giuseppe Di Benedetto (University of Palermo), Pedro António Janeiro (University of Lisbon), Massimo Lauria (University of Reggio Calabria), Francesco Maggio (University of Palermo), Renato Teofilo Giuseppe Morganti (University of L’Aquila), Frida Pashako (Epoka University of Tirana), Alexander Pellnitz (THM University of Giessen), Dario Russo (University of Palermo), Francesca Scalisi (DEMETRA Ce.Ri.Med.), Andrea Sciascia (University of Palermo), Paolo Tamborrini (Polytechnic of Torino), Marco Trisciuoglio (Polytechnic of Torino) Each book in the publishing series is subject to a double-blind peer review process In the case of an edited collection, only the papers of the Editors are not subject to the afore - mentioned process since they are experts in their field of study Volume 2 Edited by Giuseppe De Giovanni and Francesca Scalisi PRO-INNOVATION: PROCESS, PRODUCTION, PRODUCT Palermo University Press | Palermo (Italy) ISBN (print): 978-88-5509-052-0 ISBN (online): 978-88-5509-055-1 ISSN (print): 2704-6087 ISSN (online): 2704-615X Printed in August 2019 by Fotograph srl | Palermo Editing and typesetting by DEMETRA CE.R I.M ED .. on behalf of NDF Book cover and graphic design by Cesare Sposito Promoter DEMETRA CE.R I.M ED . -

Fibrous Tissue Ring: an Uncommon Cause of Severe Prosthetic Valve Stenosis

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Elsevier - Publisher Connector The Journal of Thoracic and Cardiovascular Surgery Brief communications 12 5 3 Volume 109, Number 6 FIBROUS TISSUE RING: AN UNCOMMON CAUSE OF SEVERE PROSTHETIC VALVE STENOSIS Paolo Masiello, MD, Vincenzo Cassano, MD, and Giuseppe Di Benedetto, MD, Salerno, Italy We describe here the case of a patient in whom severe mitral stenosis and periprosthetic leak developed 5 years after mitral valve replacement with a Medtronic Hall prosthesis (Medtronic, Inc., Minrie.apolis, Minn.). Mitral valve stenosis was attributed to the~formation of concen- tric dense fibrous tissue around the atrial side of the anulus. A 45-year-old woman underwent open mitral commis- surotomy in 1979 for rheumatic mitral stenosis. Ten years later she underwent mitral valve replacement with a Medtronic Hall 27 mm prosthesis. In 1993 she had a fever of unknown origin. Subsequently her clinical status pro- gressively worsened, with the onset of exertional dyspnea and fatigue. In March 1994 she was referred to us. On admission severe peripheral edema and jugular vein dis- tention were present. The liver was palpable 6 cm below the costal border. A 2/6 to 3/6 soft holosystolic murmur was audible on the apex radiating to the axilla. Blood pressure was 130/80 mm Hg. The electrocardiogram showed sinus rhythm with a heart rate of 96 beats/min and signs of moderate right ventricular hypertrophy. The chest x-ray film revealed a slightly enlarged cardiac shadow and pulmonary congestion. A transthoracic two-dimensional and Doppler echocardiogram showed left atrial dilatation, normal opening of the prosthesis, reduction of diastolic flow through the prosthesis, and a mild periprosthetic leak. -

PRELIMINARY PROGRAM Nov. 7Th,2016

PRELIMINARY PROGRAM Nov. 7th,2016 XXVIII° Congresso Nazionale Società Italiana di Cardiochirurgia Roma, 25-27Novembre, 2016 Ergife Palace Hotel TRANSLATIONAL CARDIOVASCULAR SCIENCE MEETS STANDARD AND INNOVATIVE THERAPIES PAROLE CHIAVE: Cardiochirurgia, educational, training, tecnica chirurgica. - Il congresso è destinato a professionisti medici chirurghi nel settore della Chirurgia cardiaca - Le ore formative previste sono: 31 Segreteria organizzativa G.C. Srl Via della Camilluccia 535 00135 - ROMA Tel + 39.06.85305059 E-mail: [email protected] 2 FRIDAY, NOV. 25TH TECHNO-GRADUATE: ADULT CARDIAC MAIN ROOM TECHNO-GRADUATE: ADULT CARDIAC SESSION 1 THE GREAT EVERLASTING DEBATE: STANDARD VS. LESS INVASIVE SURGERY CHAIR MICHELE DI MAURO (CHIETI) PIERSILVIO GEROMETTA (BERGAMO) 8.00 WHY I PREFER STANDARD CABG LORENZO MENICANTI (SAN DONATO M) 8.15 WHY I PREFER LESS INVASIVE CABG CLAUDIO MUNERETTO (BRESCIA) 8.30 FIVE MINUTES REBUTTAL MENICANTI - MUNERETTO 8.40 WHY I PREFER STANDARD AVR ROBERTO DI BARTOLOMEO (BOLOGNA) 8.55 WHY I PREFER LESS INVASIVE AVR MATTIA GLAUBER (MILANO) 9.10 FIVE MINUTES REBUTTAL DI BARTOLOMEO - GLAUBER 9.20 WHY I PREFER STANDARD MV PROCEDURES OTTAVIO ALFIERI (MILANO) 9.35 WHY I PREFER LESS INVASIVE MV PROCEDURES FRANCESCO MUSUMECI (ROMA) 9.50 FIVE MINUTES REBUTTAL ALFIERI - MUSUMECI 10.00-10.30 STANDS VISIT MAIN ROOM TECHNO-GRADUATE: ADULT CARDIAC SESSION 2 VALVES, VALVES, AND AGAIN VALVES! CHAIR MAURO RINALDI (TORINO) UGOLINO LIVI (UDINE) 10.30 PERCEVAL VALVE: FROM SELECTIVE TO ROUTINE USE GIOVANNI TROISE (BRESCIA) AVR WITH EDWARDS INTUITY ELITE: A REAL MINIMALLY INVASIVE 10.45 MARCO DI EUSANIO (ANCONA) APPROACH NEXT GENERATION OF SURGICAL AORTIC PERICARDIAL VALVE: AVALUS. 11.00 A. -

PASS Information Title Cilostazol Drug Utilisation Study

PASS Information Title Cilostazol drug utilisation study Protocol version Version 2 identifier Date of last version of February 28, 2013 protocol EU PAS register number Registration is planned prior to study initiation once the protocol is final and has received regulatory endorsement by the Committee for Medicinal Products for Human Use (CHMP) Active substance Cilostazol, ATC code B01AC23, Platelet aggregation inhibitors excluding heparin Medicinal product Pletal, Ekistol Product reference UK/H/0291/001 and 002 Procedure number EMEA/H/A-31/1306 Marketing authorisation Otsuka Pharmaceutical Europe Ltd. holder(s) (MAH) Lacer S.A. Joint PASS No Research question and This study protocol was developed in the context of the European objectives Medicines Agency (EMA) referral (article 31 of Council Directive 2001/83/EC) on the risks and benefits of the use of cilostazol. The study objectives are to characterise patients using cilostazol according to demographics, comorbidity, comedications, and duration of treatment. In addition, the study will describe the dosing of cilostazol, the prescribing physician specialties, and the potential off-label prescribing. Country(-ies) of study Spain, United Kingdom, Germany, Sweden Author Jordi Castellsague, MD, MPH; Cristina Varas-Lorenzo, MD, MPH, PhD; Susana Perez-Gutthann, MD, MPH, PhD RTI Health Solutions Trav. Gracia 56 Atico 1 08006 Barcelona, Spain Telephone: +34.93.241.7766 Fax: +34.93.414.2610 E-mail: [email protected] CONFIDENTIAL 1 of 56 Marketing Authorisation Holder(s) Marketing authorisation -

Annual Report July 1, 2009 – June 30, 2010

Department of Surgery annual Report July 1, 2009 – June 30, 2010 R.S. McLaughLin PRofessoR and chaiR Dr. R.K. Reznick (May 24, 2010) Dr. D.A. Latter (Interim Chair July 1, 2010 to March 31, 2011) aSSociaTe chaiR and Vice–chaiRS Dr. B.R. Taylor Associate Chair / James Wallace McCutcheon Chair in Surgery Dr. D.A. Latter Vice-Chair, Education Dr. R.R. Richards Vice-Chair, Clinical Dr. B. Alman Vice-Chair, Research / A.J. Latner Professor and Chair of Orthopaedic Surgery SuRGEONS in chief Dr. J.G. Wright The Hospital for Sick Children / Robert B. Salter Chair in Surgical Research Dr. J.S. Wunder Mount Sinai Hospital / Rubinoff-Gross Chair in Orthopaedic Surgery Dr. L.C. Smith St. Joseph’s Health Centre Dr. O.D. Rotstein St. Michael’s Hospital Dr. R.R. Richards Sunnybrook Health Sciences Centre Dr. L. Tate The Toronto East General Hospital Dr. B.R. Taylor University Health Network / James Wallace McCutcheon Chair in Surgery Dr. J.L. Semple Women’s College Hospital uniVeRSiTY diViSion chaiRS Dr. M.J. Wiley Anatomy Dr. C. Caldarone Cardiac Surgery Dr. A. Smith General Surgery / Bernard and Ryna Langer Chair Dr. J.T. Rutka Leslie Dan Professor and Chair of Neurosurgery Dr. B. Alman A.J. Latner Professor and Chair of Orthopaedic Surgery Dr. D. Anastakis Plastic Surgery Dr. S. Keshavjee F.G. Pearson / R.J. Ginsberg Chair in Thoracic Surgery Dr. S. Herschorn Martin Barkin Chair in Urological Research Dr. T. Lindsay Vascular Surgery Department of Surgery 2009-2010 Annual Report | 1 TabLe of conTents Chair’s Report. -

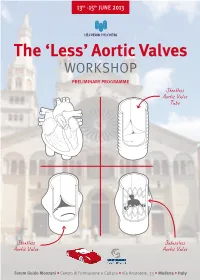

Aortic Valves WORKSHOP PRELIMINARY PROGRAMME

13th - 15th JUNE 2013 The ‘Less’ Aortic Valves WORKSHOP PRELIMINARY PROGRAMME Forum Guido Monzani • Centro di Formazione e Cultura • Via Aristotele, 33 • Modena • Italy THE ‘LESS’ AORTIC VALVES WORKSHOP Hesperia Hospital Davide Gabbieri Modena, Italy Hesperia Hospital Modena, Italy Filippo Benassi Azienda Ospedaliero Universitaria di Parma Parma, Italy Clorinda Labia Hesperia Hospital Modena, Italy Guglielmo Stefanelli Emanuela Angeli Hesperia Hospital University of Bologna Modena, Italy Bologna, Italy Guglielmo Stefanelli ESCVS - European Society for Hesperia Hospital Cardiovascular and Endovascular Surgery Modena, Italy SICCH - Italian Society for Cardiac Surgery Josè Luis Pomar EACTS - European Association Hospital Clínico for Cardio-Thoracic Surgery University of Barcelona Barcelona, Spain University of Bologna Regione Emilia-Romagna Roberto Di Bartolomeo Policlinico S.Orsola-Malpighi Comune di Modena University of Bologna Bologna, Italy UNDER REQUEST * 2 13th > 15th JUNE 2013 The ‘Less’ Aortic Valves WORKSHOP ‘Less’ aortic valve symposium is a two-days interactive workshop focused on stentless aortic prostheses, sutureless aortic valves and stentless aortic valved conduits. During the course a faculty of world leaders in the field will discuss and analyze with you the outcomes and problems related to the 1st generation porcine stentless aortic valves and the advantages of the pericardial stentless prostheses, along with the more appropriate techniques of implant. Theoretical and practical benefits of sutureless aortic implants will be reported, particularly in minimally-invasive approaches. The final topic concern the results reported by different experiences with the use of biological materials in surgery of the aortic root and Bentall operations with stentless conduits. During a two- hours lunch video session, twelve 5’ videos followed by 5’ discussion, collected by the scientific committee will be chosen, illustrating interesting case-reports or details of innovative surgical techniques. -

Human Respiratory Epithelium: Control of Ciliary

iiiiii mi i ii m i n i m m i i l l i n i u m iiiii 2807400791 HUMAN RESPIRATORY EPITHELIUM: CONTROL OF CILIARY ACTIVITY AND TECHNIQUES OF INVESTIGATION by Giuseppe Di Benedetto MEDICAL LIBRARY. ROYAL FREE HOSPITAL HAMPSTEAD. A thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the University of London Department of Thoracic Medicine Royal Free Hospital and School of Medicine September 1990 1 ProQuest Number: 10631083 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a com plete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. uest ProQuest 10631083 Published by ProQuest LLC(2017). Copyright of the Dissertation is held by the Author. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States C ode Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. ProQuest LLC. 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106- 1346 ^OS 1 ^ ABSTRACT In man, most of the upper airways and the tracheo-bronchial tree down to the non alveolar walls of the respiratory bronchioles are covered by ciliated epithelium. Mucociliary clearance is the most important clearing mechanism of the respiratory tract and is the result of beating cilia propelling the overlying secretions, carrying both trapped inhaled material and locally produced biological debris, toward the oropharynx. The rate of mucus transport is determined by the power produced by each cilium and the number of cilia in contact with the mucus. -

01 Cardio 4-12

Monaldi Arch Chest Dis 2012; 78: 210-2011 CASE REPORT Anterior mitral valve aneurysm perforation in a patient with preexisting aortic regurgitation Perforazione di aneurisma del lembo mitralico anteriore in un paziente con preesistente rigurgito aortico Rodolfo Citro, Angelo Silverio, Roberto Ascoli, Antonio Longobardi, Eduardo Bossone, Giuseppe Di Benedetto, Federico Piscione ABSTRACT: Anterior mitral valve aneurysm perforation in a pa- occurs as a complication of endocarditis but may also be as- tient with preexisting aortic regurgitation. R. Citro, A. Silverio, sociated with other diseases, in particular connective tissue R. Ascoli, A. Longobardi, E. Bossone, G. Di Benedetto, F. Piscione. disorders. In the present case, the absence of such etiology We report the case of a 71-year-old man hospitalized suggests a possible role for of aortic regurgitation in MVA for acute heart failure. Transthoracic and transesophageal rupture secondary to a “jet lesion” mechanism. echocardiography showed mitral valve aneurysm (MVA) Keywords: mitral valve aneurysm, mitral regurgitation, rupture and severe mitral regurgitation. No vegetations but aortic regurgitation. significant aortic regurgitation were also observed. MVA perforation is a rare life-threatening condition that typically Monaldi Arch Chest Dis 2012; 78: 210-211. Heart Department, University Hospital “San Giovanni di Dio e Ruggi d’Aragona”, Salerno, Italy. Corresponding author: Rodolfo Citro, MD, FESC; University Hospital “San Giovanni di Dio e Ruggi d’Aragona”; Heart Tower Room 810; Largo Città di Ippocrate, I-84131 Salerno, Italy; Phone: +39 089 673377; Tel: +39 033 227 8934; Fax: +39 033 239 3309; Mobile +39 3473570880; E-mail address: [email protected] Case report of the aortic root showed moderate aortic regurgita- tion. -

Mariani Participatory 2020.Pdf

Open Access Publishing Series in PROJECT | Essays and Researches 3 RESILIENCE BETWEEN MITIGATION AND ADAPTATION Edited by Fabrizio Tucci Cesare Sposito Open Access Publishing Series in PROJECT | Essays and Researches Editor in Chief Cesare Sposito (University of Palermo) International Scientific Committee Carlo Atzeni (University of Cagliari), Jose Ballesteros (Polytechnic University of Madrid), Mario Bisson ( Polytechnic of Milano) , Tiziana Campisi (University of Palermo), Maurizio Carta (University of Palermo), Xavier Casanovas (Polytechnic of Catalunya), Giuseppe De Giovanni (University of Palermo), Clice de Toledo Sanjar Mazzilli (University of São Paulo), Giuseppe Di Benedetto (University of Palermo), Manuel Gausa (University of Genova), Pedro António Janeiro (University of Lisbon), Massimo Lauria (University of Reggio Calabria), Francesco Maggio (University of Palermo), Renato Teofilo Giuseppe Morganti (University of L’Aquila), Elodie Nourrigat (Ecole Nationale Supérieure d’Architecture Montpellier), Frida Pashako (Epoka University of Tirana), Monica Rossi-Schwarzenbeck (Leipzig University of Applied Sciences), Rubén García Rubio (Tulane University, New Orleans), Dario Russo (University of Palermo), Francesca Scalisi (DEMETRA Ce.Ri.Med.), Andrea Sciascia (University of Palermo), Marco Sosa (Zayed University, Abu Dhabi), Paolo Tamborrini (Polytechnic of Torino), Marco Trisciuoglio (Polytechnic of Torino) Each book in the publishing series is subject to a double-blind peer review process In the case of an edited collection, only the papers of the Editors can be not subject to the aforementioned process if they are experts in their field of study Volume 3 Edited by Fabrizio Tucci and Cesare Sposito RESILIENCE BETWEEN MITIGATION AND ADAPTATION Palermo University Press | Palermo (Italy) ISBN (print): 978-88-5509-094-0 ISBN (online): 978-88-5509-096-4 ISSN (print): 2704-6087 ISSN (online): 2704-615X Printed in January 2020 by Fotograph srl | Palermo Editing and typesetting by DEMETRA CE.R I.M ED . -

Computational and Financial Econometrics (CFE 2018)

CFE-CMStatistics 2018 PROGRAMME AND ABSTRACTS 12th International Conference on Computational and Financial Econometrics (CFE 2018) http://www.cfenetwork.org/CFE2018 and 11th International Conference of the ERCIM (European Research Consortium for Informatics and Mathematics) Working Group on Computational and Methodological Statistics (CMStatistics 2018) http://www.cmstatistics.org/CMStatistics2018 University of Pisa, Italy 14 – 16 December 2018 c ECOSTA ECONOMETRICS AND STATISTICS. All rights reserved. I CFE-CMStatistics 2018 ISBN 978-9963-2227-5-9 c 2018 - ECOSTA ECONOMETRICS AND STATISTICS All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any other form or by any means without the prior permission from the publisher. II c ECOSTA ECONOMETRICS AND STATISTICS. All rights reserved. CFE-CMStatistics 2018 International Organizing Committee: Ana Colubi, Erricos Kontoghiorghes, Herman Van Dijk and Caterina Giusti. CFE 2018 Co-chairs: Alessandra Amendola, Michael Owyang, Dimitris Politis and Toshiaki Watanabe. CFE 2018 Programme Committee: Francesco Audrino, Christopher Baum, Monica Billio, Christian Brownlees, Laura Coroneo, Richard Fairchild, Luca Fanelli, Lola Gadea, Alain Hecq, Benjamin Holcblat, Rustam Ibragimov, Florian Ielpo, Laura Jackson, Robert Kohn, Degui Li, Alessandra Luati, Svetlana Makarova, Claudio Morana, Teruo Nakatsuma, Yasuhiro Omori, Alessia Paccagnini, Sandra Paterlini, Ivan Paya, Christian Proano, Artem Prokhorov, Arvid Raknerud, Joern Sass, Willi Semmler, Etsuro -

Rosario MANCUSI

Curriculum Vitae Dott. Rosario MANCUSI INFORMAZIONI PERSONALI Rosario MANCUSI Via Acquedotto 26, 80077 Ischia (NA), Italia +39 339 7987208 [email protected] www.mamamedicaspa.com Twitter @rosario_mancusi Facebook /rosario.mancusi.9 Linkedin.com /in/rosario-mancusi-503a1a49 Sesso Maschio Data di nascita 29/06/1969 Nazionalità Italiana Codice Fiscale MNCRSR69H29E329Y P.IVA 0433821219 Leva Militare Congedo illimitato del 07.06.1996 ai sensi dell’art.100 D.P.R. 237/64 POSIZIONE RICOPERTA Responsabile Unità Operativa di Chirurgia Vascolare ed Endovascolare Presidio Ospedaliero Privato Accreditato Villa dei Fiori Corso Italia 157, 80011 Acerra (NA) TITOLO DI STUDIO Laureato in Medicina e Chirurgia, specializzato in Chirurgia Toracica ed in Chirurgia Vascolare ISCRIZIONE ALBO Medici-Chirurghi di Napoli dal 2/03/1994 Numero 26819 DICHIARAZIONI PERSONALI Importanti capacità comunicative ed organizzative per la gestione di un reparto medico- chirurgico per il trattamento della patologia cardio-toraco-vascolare, del personale medico, infermieristico e paramedico. Eccellenti capacità formative per giovani chirurghi Primo operatore in chirurgia cardiaca adulti, chirurgia toracica e chirurgia vascolare ed endovascolare © Unione europea, 2002-2015 | europass.cedefop.europa.eu Pagina 1 / 30 Curriculum Vitae Dott. Rosario Mancusi ESPERIENZA PROFESSIONALE Settembre 2013 ad oggi Responsabile U.O. Chirurgia Vascolare ed Endovascolare Presidio Ospedaliero Privato Accreditato Villa dei Fiori, Acerra (NA) ▪ Responsabile, primo operatore Attività: Chirurgia vascolare ed endovascolare arteriosa e venosa Dicembre 2010 – Settembre 2013 Aiuto Responsabile U.O. Chirurgia Vascolare ed Endovascolare Presidio Ospedaliero Privato Accreditato Villa dei Fiori, Acerra (NA) Responsabile Dott. Pasquale Valitutti ▪ Aiuto Responsabile, primo e secondo operatore Attività: Chirurgia vascolare ed endovascolare arteriosa e venosa Gennaio 2009 – Maggio 2010 Perfezionamento ed aggiornamento professionale U.O.S.C. -

Il Bilancio Di Due Anni Di Attività Aneurismi Dell'aorta Ascendente E

Rivista dell’associazione nazionale Medici caRdiologi ospedalieRi – anMco gennaio • febbraio area aritmie: il bilancio di due anni di attività aneurismi dell’aorta ascendente e insufficienza valvolare aortica: una relazione da codificare 2013 n°191 imaging integrato cardiovascolare siamo partiti! la cardiologia ospedaliera al bivio: problema od opportunità? linee programmatiche dell’area nursing per il biennio 2013 - 2014 i programmi per il prossimo biennio dell’area prevenzione tra continuità, collaborazione, “concretezza” e... colori! sindromi coronariche acute: dalle linee guida europee al paziente del mondo reale la cardio - oncologia in toscana tra luci ed ombre donne e prevenzione cardiovascolare il giovane cardiologo fra tecnologia e clinica Un centenario della cardiologia: la malattia di chagas 10 consigli d’autore nella cura dello steMi omaggio a Rocca imperiale amici dell’ anmco: B oeHRingeR ingelHeiM SIMO ANN TE IV N ER A S U A Q R N I I O C 44° Congresso Nazionale 1 9 3 6 3 - 2 0 1 di Cardiologia ANMCO Firenze - Fortezza da Basso | 30 maggio - 1 giugno 2013 ANMCO 50 anni uniti nel cuore... Cinquantesimo anniversario della nascita dell’Associazione Nazionale Medici Cardiologi Ospedalieri - ANMCO Cinquantesimo anniversario dalla nascita dell’Associazione Nazionale Medici Cardiologi Ospedalieri i ndice Rivista dell’associazione nazionale Medici caRdiologi ospedalieRi – anMco gennaio • febbraio area aritmie: il bilancio di due anni di attività aneurismi dell’aorta ascendente e insufficienza valvolare aortica: una relazione da codificare 2013 n°191 imaging integrato cardiovascolare siamo partiti! dALLe ARee AReA nURSinG la cardiologia ospedaliera al bivio: problema od opportunità? linee programmatiche Linee Programmatiche p. 23 dell’area nursing per il biennio 2013 - 2014 i programmi per il prossimo biennio dell’area prevenzione dell’Area nursing tra continuità, collaborazione, AReA ARiTMie “concretezza” e..