Use-Case the Hub of Software2.0 Development IVAR JACOBSON, IAN SPENCE, and BRIAN KERR

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Writing and Reviewing Use-Case Descriptions

Bittner/Spence_06.fm Page 145 Tuesday, July 30, 2002 12:04 PM PART II WRITING AND REVIEWING USE-CASE DESCRIPTIONS Part I, Getting Started with Use-Case Modeling, introduced the basic con- cepts of use-case modeling, including defining the basic concepts and understanding how to use these concepts to define the vision, find actors and use cases, and to define the basic concepts the system will use. If we go no further, we have an overview of what the system will do, an under- standing of the stakeholders of the system, and an understanding of the ways the system provides value to those stakeholders. What we do not have, if we stop at this point, is an understanding of exactly what the system does. In short, we lack the details needed to actually develop and test the system. Some people, having only come this far, wonder what use-case model- ing is all about and question its value. If one only comes this far with use- case modeling, we are forced to agree; the real value of use-case modeling comes from the descriptions of the interactions of the actors and the system, and from the descriptions of what the system does in response to the actions of the actors. Surprisingly, and disappointingly, many teams stop after developing little more than simple outlines for their use cases and consider themselves done. These same teams encounter problems because their use cases are vague and lack detail, so they blame the use-case approach for having let them down. The failing in these cases is not with the approach, but with its application. -

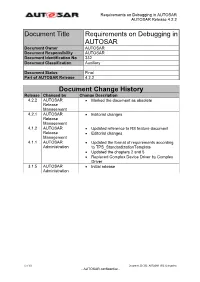

Document Title Requirements on Debugging in AUTOSAR

Requirements on Debugging in AUTOSAR AUTOSAR Release 4.2.2 Document Title Requirements on Debugging in AUTOSAR Document Owner AUTOSAR Document Responsibility AUTOSAR Document Identification No 332 Document Classification Auxiliary Document Status Final Part of AUTOSAR Release 4.2.2 Document Change History Release Changed by Change Description 4.2.2 AUTOSAR Marked the document as obsolete Release Management 4.2.1 AUTOSAR Editorial changes Release Management 4.1.2 AUTOSAR Updated reference to RS feature document Release Editorial changes Management 4.1.1 AUTOSAR Updated the format of requirements according Administration to TPS_StandardizationTemplate Updated the chapters 2 and 5 Replaced Complex Device Driver by Complex Driver 3.1.5 AUTOSAR Initial release Administration 1 of 19 Document ID 332: AUTOSAR_SRS_Debugging - AUTOSAR confidential - Requirements on Debugging in AUTOSAR AUTOSAR Release 4.2.2 Disclaimer This specification and the material contained in it, as released by AUTOSAR, is for the purpose of information only. AUTOSAR and the companies that have contributed to it shall not be liable for any use of the specification. The material contained in this specification is protected by copyright and other types of Intellectual Property Rights. The commercial exploitation of the material contained in this specification requires a license to such Intellectual Property Rights. This specification may be utilized or reproduced without any modification, in any form or by any means, for informational purposes only. For any other purpose, no part of the specification may be utilized or reproduced, in any form or by any means, without permission in writing from the publisher. The AUTOSAR specifications have been developed for automotive applications only. -

The Guide to Succeeding with Use Cases

USE-CASE 2.0 The Guide to Succeeding with Use Cases Ivar Jacobson Ian Spence Kurt Bittner December 2011 USE-CASE 2.0 The Definitive Guide About this Guide 3 How to read this Guide 3 What is Use-Case 2.0? 4 First Principles 5 Principle 1: Keep it simple by telling stories 5 Principle 2: Understand the big picture 5 Principle 3: Focus on value 7 Principle 4: Build the system in slices 8 Principle 5: Deliver the system in increments 10 Principle 6: Adapt to meet the team’s needs 11 Use-Case 2.0 Content 13 Things to Work With 13 Work Products 18 Things to do 23 Using Use-Case 2.0 30 Use-Case 2.0: Applicable for all types of system 30 Use-Case 2.0: Handling all types of requirement 31 Use-Case 2.0: Applicable for all development approaches 31 Use-Case 2.0: Scaling to meet your needs – scaling in, scaling out and scaling up 39 Conclusion 40 Appendix 1: Work Products 41 Supporting Information 42 Test Case 44 Use-Case Model 46 Use-Case Narrative 47 Use-Case Realization 49 Glossary of Terms 51 Acknowledgements 52 General 52 People 52 Bibliography 53 About the Authors 54 USE-CASE 2.0 The Definitive Guide Page 2 © 2005-2011 IvAr JacobSon InternationAl SA. All rights reserved. About this Guide This guide describes how to apply use cases in an agile and scalable fashion. It builds on the current state of the art to present an evolution of the use-case technique that we call Use-Case 2.0. -

INCOSE: the FAR Approach “Functional Analysis/Allocation and Requirements Flowdown Using Use Case Realizations”

in Proceedings of the 16th Intern. Symposium of the International Council on Systems Engineering (INCOSE'06), Orlando, FL, USA, Jul 2006. The FAR Approach – Functional Analysis/Allocation and Requirements Flowdown Using Use Case Realizations Magnus Eriksson1,2, Kjell Borg1, Jürgen Börstler2 1BAE Systems Hägglunds AB 2Umeå University SE-891 82 Örnsköldsvik SE-901 87 Umeå Sweden Sweden {magnus.eriksson, kjell.borg}@baesystems.se {magnuse, jubo}@cs.umu.se Copyright © 2006 by Magnus Eriksson, Kjell Borg and Jürgen Börstler. Published and used by INCOSE with permission. Abstract. This paper describes a use case driven approach for functional analysis/allocation and requirements flowdown. The approach utilizes use cases and use case realizations for functional architecture modeling, which in turn form the basis for design synthesis and requirements flowdown. We refer to this approach as the FAR (Functional Architecture by use case Realizations) approach. The FAR approach is currently applied in several large-scale defense projects within BAE Systems Hägglunds AB and the experience so far is quite positive. The approach is illustrated throughout the paper using the well known Automatic Teller Machine (ATM) example. INTRODUCTION Organizations developing software intensive defense systems, for example vehicles, are today faced with a number of challenges. These challenges are related to the characteristics of both the market place and the system domain. • Systems are growing ever more complex, consisting of tightly integrated mechanical, electrical/electronic and software components. • Systems have very long life spans, typically 30 years or longer. • Due to reduced acquisition budgets, these systems are often developed in relatively short series; ranging from only a few to several hundred units. -

UML Tutorial: Part 1 -- Class Diagrams

UML Tutorial: Part 1 -- Class Diagrams. Robert C. Martin My next several columns will be a running tutorial of UML. The 1.0 version of UML was released on the 13th of January, 1997. The 1.1 release should be out before the end of the year. This col- umn will track the progress of UML and present the issues that the three amigos (Grady Booch, Jim Rumbaugh, and Ivar Jacobson) are dealing with. Introduction UML stands for Unified Modeling Language. It represents a unification of the concepts and nota- tions presented by the three amigos in their respective books1. The goal is for UML to become a common language for creating models of object oriented computer software. In its current form UML is comprised of two major components: a Meta-model and a notation. In the future, some form of method or process may also be added to; or associated with, UML. The Meta-model UML is unique in that it has a standard data representation. This representation is called the meta- model. The meta-model is a description of UML in UML. It describes the objects, attributes, and relationships necessary to represent the concepts of UML within a software application. This provides CASE manufacturers with a standard and unambiguous way to represent UML models. Hopefully it will allow for easy transport of UML models between tools. It may also make it easier to write ancillary tools for browsing, summarizing, and modifying UML models. A deeper discussion of the metamodel is beyond the scope of this column. Interested readers can learn more about it by downloading the UML documents from the rational web site2. -

Plantuml Language Reference Guide (Version 1.2021.2)

Drawing UML with PlantUML PlantUML Language Reference Guide (Version 1.2021.2) PlantUML is a component that allows to quickly write : • Sequence diagram • Usecase diagram • Class diagram • Object diagram • Activity diagram • Component diagram • Deployment diagram • State diagram • Timing diagram The following non-UML diagrams are also supported: • JSON Data • YAML Data • Network diagram (nwdiag) • Wireframe graphical interface • Archimate diagram • Specification and Description Language (SDL) • Ditaa diagram • Gantt diagram • MindMap diagram • Work Breakdown Structure diagram • Mathematic with AsciiMath or JLaTeXMath notation • Entity Relationship diagram Diagrams are defined using a simple and intuitive language. 1 SEQUENCE DIAGRAM 1 Sequence Diagram 1.1 Basic examples The sequence -> is used to draw a message between two participants. Participants do not have to be explicitly declared. To have a dotted arrow, you use --> It is also possible to use <- and <--. That does not change the drawing, but may improve readability. Note that this is only true for sequence diagrams, rules are different for the other diagrams. @startuml Alice -> Bob: Authentication Request Bob --> Alice: Authentication Response Alice -> Bob: Another authentication Request Alice <-- Bob: Another authentication Response @enduml 1.2 Declaring participant If the keyword participant is used to declare a participant, more control on that participant is possible. The order of declaration will be the (default) order of display. Using these other keywords to declare participants -

A Study on Process Description Method for DFM Using Ontology

Invited Paper A Study on Process Description Method for DFM Using Ontology K. Hiekata1 and H. Yamato2 1Department of Systems Innovation, Graduate School of Engineering, The University of Tokyo, 5-1-5, Kashiwanoha, Kashiwa-city, Chiba 277-8563, Japan 2Department of Human and Engineered Environmental Studies, Graduate School of Frontier Sciences, The University of Tokyo, 5-1-5, Kashiwanoha, Kashiwa-city, Chiba 277-8563, Japan [email protected], [email protected] Abstract A method to describe process and knowledge based on RDF which is an ontology description language and IDEF0 which is a formal process description format is proposed. Once knowledge of experienced engineers is embedded into the system the knowledge will be lost in the future. A production process is described in a proposed format similar to BOM and the process can be retrieved as a flow diagram to make the engineers to understand the product and process. Proposed method is applied to a simple production process of common sub-assembly of ships for evaluation. Keywords: Production process, DFM, Ontology, Computer system 1 INTRODUCTION (Unified Resource Identifier) is assigned to all the objects, There are many research and computer program for and metadata is defined for all objects using the URI. supporting optimization of production process in Metadata is defined as a statement with subject, shipyards. And knowledge of experienced engineers is predicate and object. The statement is called triple in embedded into the system. Once the knowledge is RDF. Two kinds of elements, Literal or Resource, can be embedded into computer system, the knowledge is not a component of a statement. -

Use Case Tutorial Version X.X ● April 18, 2016

Use Case Tutorial Version X.x ● April 18, 2016 Company Name Limited Street City, State ZIP Country phone: +1 000 123 4567 Company Name Limited Street City, State ZIP Country phone: +1 000 123 4567 Company Name Limited Street City, State ZIP Country phone: +1 000 123 4567 www.website.com [Company Name] [Document Name] [Project Name] [Version Number] Table of Contents Introduction ..............................................................................................3 1. Use cases and activity diagrams .......................................................4 1.1. Use case modelling ....................................................................4 1.2. Use cases and activity diagrams ..................................................7 1.3. Actors .......................................................................................7 1.4. Describing use cases.................................................................. 8 1.5. Scenarios ................................................................................10 1.6. More about actors ....................................................................13 1.7. Modelling the relationships between use cases ...........................15 1.8. Stereotypes .............................................................................15 1.9. Sharing behaviour between use cases........................................ 16 1.10. Alternatives to the main success scenario ..................................17 1.11. To extend or include? ...............................................................20 -

User-Stories-Applied-Mike-Cohn.Pdf

ptg User Stories Applied ptg From the Library of www.wowebook.com The Addison-Wesley Signature Series The Addison-Wesley Signature Series provides readers with practical and authoritative information on the latest trends in modern technology for computer professionals. The series is based on one simple premise: great books come from great authors. Books in the series are personally chosen by expert advi- sors, world-class authors in their own right. These experts are proud to put their signatures on the cov- ers, and their signatures ensure that these thought leaders have worked closely with authors to define topic coverage, book scope, critical content, and overall uniqueness. The expert signatures also symbol- ize a promise to our readers: you are reading a future classic. The Addison-Wesley Signature Series Signers: Kent Beck and Martin Fowler Kent Beck has pioneered people-oriented technologies like JUnit, Extreme Programming, and patterns for software development. Kent is interested in helping teams do well by doing good — finding a style of software development that simultaneously satisfies economic, aesthetic, emotional, and practical con- straints. His books focus on touching the lives of the creators and users of software. Martin Fowler has been a pioneer of object technology in enterprise applications. His central concern is how to design software well. He focuses on getting to the heart of how to build enterprise software that will last well into the future. He is interested in looking behind the specifics of technologies to the patterns, ptg practices, and principles that last for many years; these books should be usable a decade from now. -

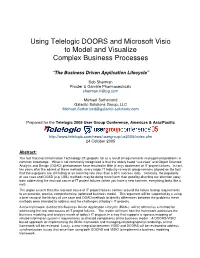

Using Telelogic DOORS and Microsoft Visio to Model and Visualize Complex Business Processes

Using Telelogic DOORS and Microsoft Visio to Model and Visualize Complex Business Processes “The Business Driven Application Lifecycle” Bob Sherman Procter & Gamble Pharmaceuticals [email protected] Michael Sutherland Galactic Solutions Group, LLC [email protected] Prepared for the Telelogic 2005 User Group Conference, Americas & Asia/Pacific http://www.telelogic.com/news/usergroup/us2005/index.cfm 24 October 2005 Abstract: The fact that most Information Technology (IT) projects fail as a result of requirements management problems is common knowledge. What is not commonly recognized is that the widely haled “use case” and Object Oriented Analysis and Design (OOAD) phenomenon have resulted in little (if any) abatement of IT project failures. In fact, ten years after the advent of these methods, every major IT industry research group remains aligned on the fact that these projects are still failing at an alarming rate (less than a 30% success rate). Ironically, the popularity of use case and OOAD (e.g. UML) methods may be doing more harm than good by diverting our attention away from addressing the real root cause of IT project failures (when you have a new hammer, everything looks like a nail). This paper asserts that, the real root cause of IT project failures centers around the failure to map requirements to an accurate, precise, comprehensive, optimized business model. This argument will be supported by a using a brief recap of the history of use case and OOAD methods to identify differences between the problems these methods were intended to address and the challenges of today’s IT projects. -

UNIT 1 UML DIAGRAMS Introduction to OOAD – Unified Process

VEL TECH HIGH TECH Dr. RANGARAJAN Dr. SAKUNTHALA ENGINEERING COLLEGE UNIT 1 UML DIAGRAMS Introduction to OOAD – Unified Process - UML diagrams – Use Case – Class Diagrams– Interaction Diagrams – State Diagrams – Activity Diagrams – Package, component and Deployment Diagrams. INTRODUCTION TO OOAD ANALYSIS Analysis is a creative activity or an investigation of the problem and requirements. Eg. To develop a Banking system Analysis: How the system will be used? Who are the users? What are its functionalities? DESIGN Design is to provide a conceptual solution that satisfies the requirements of a given problem. Eg. For a Book Bank System Design: Bank(Bank name, No of Members, Address) Student(Membership No,Name,Book Name, Amount Paid) OBJECT ORIENTED ANALYSIS (OOA) Object Oriented Analysis is a process of identifying classes that plays an important role in achieving system goals and requirements. Eg. For a Book Bank System, Classes or Objects identified are Book-details, Student-details, Membership-Details. OBJECT ORIENTED DESIGN (OOD) Object Oriented Design is to design the classes identified during analysis phase and to provide the relationship that exists between them that satisfies the requirements. Eg. Book Bank System Class name Book-Bank (Book-Name, No-of-Members, Address) Student (Name, Membership No, Amount-Paid) OBJECT ORIENTED ANALYSIS AND DESIGN (OOAD) • OOAD is a Software Engineering approach that models an application by a set of Software Development Activities. YEAR/SEM: III/V CS6502-OOAD Page 1 VEL TECH HIGH TECH Dr. RANGARAJAN Dr. SAKUNTHALA ENGINEERING COLLEGE • OOAD emphasis on identifying, describing and defining the software objects and shows how they collaborate with one another to fulfill the requirements by applying the object oriented paradigm and visual modeling throughout the development life cycles. -

Course Structure & Syllabus of B.Tech Programme In

Course Structure & Syllabus of B.Tech Programme in Information Technology (From the Session 2015-16) VSSUT, BURLA COURSE STRUCTURE FIRST YEAR (COMMON TO ALL BRANCHES) FIRST SEMESTER SECOND SEMESTER Contact Contact Theory Hrs. Theory Hrs. CR CR Course Course Subject L .T .P Subject L. T. P Code Code Mathematics-I 3 - 1 - 0 4 Mathematics-II 3 - 1 - 0 4 Physics/Chemistry 3 - 1 - 0 4 Chemistry/ Physics 3 - 1 - 0 4 Engineering Computer /CS15- CS15- Mechanics/Computer 3 - 1 - 0 4 Programming/Engineering 3 - 1 - 0 4 008 008/ Programming Mechanics Basic Electrical Engineering/ Basic Electronics/Basic 3 - 1 - 0 4 3 - 1 - 0 4 Basic Electronics Electrical Engineering English/Environmental Environmental 3 - 1 - 0 4 3 - 1 - 0 4 Studies Studies/English Sessionals Sessionals Physics Laboratory/ Chemistry Lab/ Physics 0 - 0 - 3 2 0 - 0 - 3 2 Chemistry Lab Laboratory Workshop-I/Engineering Engineering Drawing/ 0 - 0 - 3 2 0 - 0 - 3 2 Drawing Workshop-I Basic Electrical Engineering Basic Electronics Lab/Basic 0 - 0 - 3 2 0 - 0 - 3 2 Lab/Basic Electronics Lab Electrical Engineering Lab Business Communication Programming Lab/ /CS15- CS15- and Presentation Skill/ 0 - 0 - 3 2 Business Communication 0 - 0 - 3 2 984 984/ Programming Lab and Presentation Skill Total 15-5-15 28 Total 15-5-15 28 SECOND YEAR THIRD SEMESTER FOURTH SEMESTER Contact Contact Theory Hrs. Theory Hrs. CR CR Course Subject L .T .P Course Code Subject L. T. P Code Mathematics-III Computer Organization 3 - 1 - 0 4 CS15-007 and Architecture 3 - 1 - 0 4 Digital Systems 3 - 1 - 0 4 CS15-032 Theory