The Historic Collections of Lambeth Palace Library Transcript

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

And an Invitation to Help Us Preserve

HISTORICAL NOTES CONT’D (3) ST.NICHOLAS, ICKFORD. This and other Comper glass can be recognised by a tiny design of a strawberry plant in one corner. Vernon Stanley HISTORICAL NOTES ON OUR is commemorated in the Comper window at the end of GIFT AID DECLARATION the south aisle, representing St Dunstan and the Venerable WONDERFUL CHURCH Bede; the figure of Bede is supposed to have Stanley’s Using Gift Aid means that for every pound you features. give, we get an extra 28 pence from the Inland Revenue, helping your donation go further. AN ANCIENT GAME On the broad window sill of the triple window in the north aisle is scratched the frame for This means that £10 can be turned in to £12.80 a game played for many centuries in England and And an invitation to help us just so long as donations are made through Gift mentioned by Shakespeare – Nine Men’s Morris, a Aid. Imagine what a difference that could make, combination of the more modern Chinese Chequers and preserve it. and it doesn’t cost you a thing. noughts and crosses. It was played with pegs and pebbles. GILBERT SHELDON was Rector of Ickford 1636- So if you want your donation to go further, Gift 1660 and became Archbishop of Canterbury 1663-1677. Aid it. Just complete this part of the application The most distinguished person connected with this form before you send it back to us. church, he ranks amongst the most influential clerics to occupy the see of Canterbury. He became a Rector here a Name: __________________________ few years before the outbreak of the civil wars, and during that bad and difficult time he was King Charles I’s trusted Address: ____________________ advisor and friend. -

To Read This Issue

BULLETIN ofthe Assocfatfcm o(Imtish 7heol0Jfcal and 1'h ilosophlcaljjbrarfe.s BULLETIN 1975 Subscriptions: Libraries £2.00 {or $5.00 U.S.) per annum Individuals £1.00 to the Honorary Treasurer {see below) News items, notes and queries, advertisements and contributions to the Chairman {see below) COMMITTEE 1975 Chairman: Mr. John Y. Howard, New College Library {University of Edinburgh, Mound Place, Edinburgh, EH1 2LU. Vice-Chairman: Mr. John Creasey, Dr. Williams's Library, 14 Gordon Square, London, WC1 H OAG. Han. Secretary: Miss E. Mary Elliott, King's College Library {University of London), Strand, London, WC2R 2LS. Han. Treasurer: Mr. Leonard H. Elston, Kilburn Branch Library {London Borough of Camden) Cotleigh Road, London, NW6 2NP. Elected Members: Mr. R.K. Brown, Writers' Library, London Mr. G.P. Cornish, British Library Lending Division, Boston Spa Mr. R.J. Duckett, Social Sciences Library, Central Library, Bradford Mr. P.G. Jackaman, Reference Library, Fulham Library, London Miss C.A. Mackwell, Lambeth Palace Library, London Miss J.M. Owen, Sion College Library, London Miss J .M. Woods, Church Missionary Society Library, London. Co-opted Members: Mr P.W. Plumb, North East London Polytechnic Library Rev. M. J. Walsh, S.J ., Heythrop College Library {University of London) BULLETIN OF THE ASSOCIATiON OF BRITISH THEOLOGICAL AND P-HILOSOPHICAL LIBRARIES New series, no. 1, Edinburgh, December, 1974 CONTENTS Page Association news and announcements Editorial 1 Reports of 1974 meetings 2 Notice of 1975 meetings 3 Handbook of theological libraries 16 Reference section Libraries 1 - Birmingham P.L. Philosophy and Religion Dept. 4 Libraries 2 - Sion College, London 5 Societies 1 - Institute of Religion and Theology 7 Bibliographies & Reference Books 1 - Handbook of the I.R.T. -

The Cathedral and Metropolitical Church of Christ, Canterbury

THE CATHEDRAL AND METROPOLITICAL CHURCH OF CHRIST, CANTERBURY The Reverend C P Irvine in Residence 9 WEDNESDAY 7.30 Morning Prayer – Our Lady Martyrdom 6 THE THIRD 8.00 Holy Communion (BCP) – High Altar 8.00 Holy Communion – Holy Innocents, Crypt SUNDAY p236, readings p194 Gilbert Sheldon, 10.00 Diocesan Schools’ Day opening worship – Nave th BEFORE 78 Archbishop, 1677 There is no 12.30 Holy Communion today ADVENT 9.30 Morning Prayer (said) – Quire Psalms 20; 90 1.15 Diocesan Schools’ Day closing worship – Nave The Twenty-Fourth 11.00 SUNG EUCHARIST – Quire Sunday after Trinity Psalms 17.1-9; 150 5.30 EVENSONG Responses – Rose (BCP) Mozart Missa Brevis in C K259 Hymns 410; Men’s voices I sat down – Bairstow 311 t310; 114 Blatchly St Paul’s Service Psalm 49 Te lucis ante terminum – Tallis Hymn 248ii Preacher: The Reverend C P Irvine, Vice Dean 3.15 EVENSONG Responses – Holmes 10 THURSDAY 7.30 Morning Prayer – Our Lady Martyrdom attended by the Cathedral Company of Change Ringers 8.00 Holy Communion – St Nicholas, Crypt Psalm 40 Leo the Great, 10.00 Diocesan Schools’ Day opening worship – Nave Howells Dallas Service Collection Hymn Bishop of Rome, Jubilate Deo – Gabrieli ‘The Bellringers’ Hymn’ Teacher of the Faith, 1.15 Diocesan Schools’ Day closing worship – Nave 461 6.30 Sermon and Compline Justus, 4th Archbishop, 5.30 EVENSONG Responses – Aston Preacher: The Reverend N C Papadopulos, Canon Treasurer 627 or 631 Boys’ voices Kelly Jamaican Canticles Psalm 55.1-15 Give ear unto me – Marcello Hymn 186 7 MONDAY 7.30 Morning Prayer – Our -

Spotlight on Oval Content

SPOTLIGHT ON OVAL CONTENT HISTORY AND HERITAGE PAGE 2-8 TRANSPORT PAGE 9-14 Set between the neighbourhoods of Vauxhall and Kennington, Oval is a community with tree-lined EDUCATION streets and tranquil parks. A place to meet friends, PAGE 15-21 family or neighbours across its lively mosaic of new bars, cafés, shops and art galleries. A place that FOOD AND DRINK feels local but full of life, relaxed but rearing to go. PAGE 22-29 It is a place of warmth and energy, adventure and opportunity. Just a ten-minute walk from Vauxhall, CULTURE Oval and Kennington stations, Oval Village has a PAGE 30-39 lifestyle of proximity, flexibility and connectivity. PAGE 1 HISTORY AND HERITAGE A RICH HISTORY AND HERITAGE No. 1 THE KIA OVAL The Kia Oval has been the home ground of the Surrey County cricket club since 1845. It was the first ground in England to host international test cricket and in recent years has seen significant redevelopment and improved capacity. No. 2 LAMBETH PALACE For nearly 800 years, Lambeth Palace, on the banks of the river Thames, has been home to the Archbishop of Canterbury. The beautiful grounds host a series of fetes and open days whilst guided tours can be booked in order to explore the rooms and chapels of this historic working palace and home. PAGE 4 PAGE 5 No. 3 HOUSES OF PARLIAMENT The Palace of Westminster, more commonly known as the Houses of Parliament, has resided in the centre of London since the 11th Century. Formerly a royal residence it has, over the centuries, become a centre of political life. -

Lambeth Palace Library Research Guide Biographical Sources for Archbishops of Canterbury from 1052 to the Present Day

Lambeth Palace Library Research Guide Biographical Sources for Archbishops of Canterbury from 1052 to the Present Day 1 Introduction .................................................................................................................... 3 2 Abbreviations Used ....................................................................................................... 4 3 Archbishops of Canterbury 1052- .................................................................................. 5 Stigand (1052-70) .............................................................................................................. 5 Lanfranc (1070-89) ............................................................................................................ 5 Anselm (1093-1109) .......................................................................................................... 5 Ralph d’Escures (1114-22) ................................................................................................ 5 William de Corbeil (1123-36) ............................................................................................. 5 Theobold of Bec (1139-61) ................................................................................................ 5 Thomas Becket (1162-70) ................................................................................................. 6 Richard of Dover (1174-84) ............................................................................................... 6 Baldwin (1184-90) ............................................................................................................ -

STEPHEN TAYLOR the Clergy at the Courts of George I and George II

STEPHEN TAYLOR The Clergy at the Courts of George I and George II in MICHAEL SCHAICH (ed.), Monarchy and Religion: The Transformation of Royal Culture in Eighteenth-Century Europe (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2007) pp. 129–151 ISBN: 978 0 19 921472 3 The following PDF is published under a Creative Commons CC BY-NC-ND licence. Anyone may freely read, download, distribute, and make the work available to the public in printed or electronic form provided that appropriate credit is given. However, no commercial use is allowed and the work may not be altered or transformed, or serve as the basis for a derivative work. The publication rights for this volume have formally reverted from Oxford University Press to the German Historical Institute London. All reasonable effort has been made to contact any further copyright holders in this volume. Any objections to this material being published online under open access should be addressed to the German Historical Institute London. DOI: 5 The Clergy at the Courts of George I and George II STEPHEN TAYLOR In the years between the Reformation and the revolution of 1688 the court lay at the very heart of English religious life. Court bishops played an important role as royal councillors in matters concerning both church and commonwealth. 1 Royal chaplaincies were sought after, both as important steps on the road of prefer- ment and as positions from which to influence religious policy.2 Printed court sermons were a prominent literary genre, providing not least an important forum for debate about the nature and character of the English Reformation. -

John Battely's Antiquites S. Edmundi Burgi and Its Editors Francis Young

467 JOHN BATTELY'S ANTIQUITATESS. EDMUNDIBURGI AND ITS EDITORS by FRANCISYOUNG IN 1745 the first history of Bury St. Edmunds, John Battely's AntiquitatesS. EdmundiBurgiadAnnum MCCLXXII Perductae(Antiquities of St. Edmundsbury to 1272; henceforth referred to as Antiquitates), appeared in print, half a century after it was left unfinished on its author's death. The publication of this early antiquarian account of a Suffolk town was a significant event for the historiography of the county, and the work was to become the foundation for all subsequent research on the life of St. Edmund and Bury Abbey. John Battely and his work have been undeservedly forgotten; largely because he wrote in Latin for a narrow academic audience. This article will examine why and how Battely wrote a history of Bur) why the work remained unpublished for so long, and the personalities that lay behind its publication in the mid eighteenth century. Antiquitateswas a product of the antiquarianism of the seventeenth century, acutely sensitive to the political and theological implications of Saxon and mediaeval history. Battely died in 1708, already celebrated as an antiquary despite having published nothing in his lifetime, apart from one sermon on I john 5:4. His manuscripts were inherited by his nephew, Oliver Battely, but it was Dr. Thomas Terry, Greek Professor at Christchurch, Oxford, who edited his AntiquitatesRutupinae(Antiquities of Richborough') in 1711. When AntiquitatesS. EdmundiBuigiwas published in 1745, it was printed bound together with a second edition of Antiquitates Rutupinae as the complete posthumous works of John Battely. Battely's work on Bury found itself overshadowed by the earlier work; richly illustrated with maps and engravings of archaeological finds, and fully indexed, AntiquitatesRutupinae was a work of scholarship that was deemed worthy of translation into English byJohn Dunscombe as late as 1774. -

A4 Web Map 26-1-12:Layout 1

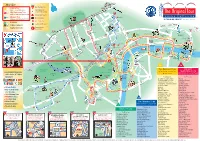

King’s Cross Start St Pancras MAP KEY Eurostar Main Starting Point Euston Original Tour 1 St Pancras T1 English commentary/live guides Interchange Point City Sightseeing Tour (colour denotes route) Start T2 W o Language commentaries plus Kids Club REGENT’S PARK Euston Rd b 3 u Underground Station r n P Madame Tussauds l Museum Tour Russell Sq TM T4 Main Line Station Gower St Language commentaries plus Kids Club q l S “A TOUR DE FORCE!” The Times, London To t el ★ River Cruise Piers ss Gt Portland St tenham Ct Rd Ru Baker St T3 Loop Line Gt Portland St B S s e o Liverpool St Location of Attraction Marylebone Rd P re M d u ark C o fo t Telecom n r h Stansted Station Connector t d a T5 Portla a m Museum Tower g P Express u l p of London e to S Aldgate East Original London t n e nd Pl t Capital Connector R London Wall ga T6 t o Holborn s Visitor Centre S w p i o Aldgate Marylebone High St British h Ho t l is und S Museum el Bank of sdi igh s B tch H Gloucester Pl s England te Baker St u ga Marylebone Broadcasting House R St Holborn ld d t ford A R a Ox e re New K n i Royal Courts St Paul’s Cathedral n o G g of Justice b Mansion House Swiss RE Tower s e w l Tottenham (The Gherkin) y a Court Rd M r y a Lud gat i St St e H n M d t ill r e o xfo Fle Fenchurch St Monument r ld O i C e O C an n s Jam h on St Tower Hill t h Blackfriars S a r d es St i e Oxford Circus n Aldwyc Temple l a s Edgware Rd Tower Hil g r n Reg Paddington P d ve s St The Monument me G A ha per T y Covent Garden Start x St ent Up r e d t r Hamleys u C en s fo N km Norfolk -

The Apostolic Succession of the Right Rev. James Michael St. George

The Apostolic Succession of The Right Rev. James Michael St. George © Copyright 2014-2015, The International Old Catholic Churches, Inc. 1 Table of Contents Certificates ....................................................................................................................................................4 ......................................................................................................................................................................5 Photos ...........................................................................................................................................................6 Lines of Succession........................................................................................................................................7 Succession from the Chaldean Catholic Church .......................................................................................7 Succession from the Syrian-Orthodox Patriarchate of Antioch..............................................................10 The Coptic Orthodox Succession ............................................................................................................16 Succession from the Russian Orthodox Church......................................................................................20 Succession from the Melkite-Greek Patriarchate of Antioch and all East..............................................27 Duarte Costa Succession – Roman Catholic Succession .........................................................................34 -

The King James Bible

Chap. iiii. The Coming Forth of the King James Bible Lincoln H. Blumell and David M. Whitchurch hen Queen Elizabeth I died on March 24, 1603, she left behind a nation rife with religious tensions.1 The queen had managed to govern for a lengthy period of almost half a century, during which time England had become a genuine international power, in part due to the stabil- ity Elizabeth’s reign afforded. YetE lizabeth’s preference for Protestantism over Catholicism frequently put her and her country in a very precarious situation.2 She had come to power in November 1558 in the aftermath of the disastrous rule of Mary I, who had sought to repair the relation- ship with Rome that her father, King Henry VIII, had effectively severed with his founding of the Church of England in 1532. As part of Mary’s pro-Catholic policies, she initiated a series of persecutions against various Protestants and other notable religious reformers in England that cumu- latively resulted in the deaths of about three hundred individuals, which subsequently earned her the nickname “Bloody Mary.”3 John Rogers, friend of William Tyndale and publisher of the Thomas Matthew Bible, was the first of her victims. For the most part, Elizabeth was able to maintain re- ligious stability for much of her reign through a couple of compromises that offered something to both Protestants and Catholics alike, or so she thought.4 However, notwithstanding her best efforts, she could not satisfy both groups. Toward the end of her life, with the emergence of Puritanism, there was a growing sense among select quarters of Protestant society Lincoln H. -

The Bishop of London, Colonialism and Transatlantic Slavery

The Bishop of London, colonialism and transatlantic slavery: Research brief for a temporary exhibition, spring 2022 and information to input into permanent displays Introduction Fulham Palace is one of the earliest and most intriguing historic powerhouses situated alongside the Thames and the last one to be fully restored. It dates back to 704AD and for over thirteen centuries was owned by the Bishop of London. The Palace site is of exceptional archaeological interest and has been a scheduled monument since 1976. The buildings are listed as Grade I and II. The 13 acres of botanical gardens, with plant specimens introduced here from all over the world in the late 17th century, are Grade II* listed. Fulham Palace Trust has run the site since 2011. We are restoring it to its former glory so that we can fulfil our vision to engage people of all ages and from all walks of life with the many benefits the Palace and gardens have to offer. Our site-wide interpretation, inspired learning and engagement programmes, and richly-textured exhibitions reveal insights, through the individual stories of the Bishops of London, into over 1,300 years of English history. In 2019 we completed a £3.8m capital project, supported by the National Lottery Heritage Fund, to restore and renew the historic house and garden. The Trust opens the Palace and gardens seven days a week free of charge. In 2019/20 we welcomed 340,000 visitors. We manage a museum, café, an award-winning schools programme (engaging over 5,640 pupils annually) and we stage a wide range of cultural events. -

Marriage Certificates

GROOM LAST NAME GROOM FIRST NAME BRIDE LAST NAME BRIDE FIRST NAME DATE PLACE Abbott Calvin Smerdon Dalkey Irene Mae Davies 8/22/1926 Batavia Abbott George William Winslow Genevieve M. 4/6/1920Alabama Abbotte Consalato Debale Angeline 10/01/192 Batavia Abell John P. Gilfillaus(?) Eleanor Rose 6/4/1928South Byron Abrahamson Henry Paul Fullerton Juanita Blanche 10/1/1931 Batavia Abrams Albert Skye Berusha 4/17/1916Akron, Erie Co. Acheson Harry Queal Margaret Laura 7/21/1933Batavia Acheson Herbert Robert Mcarthy Lydia Elizabeth 8/22/1934 Batavia Acker Clarence Merton Lathrop Fannie Irene 3/23/1929East Bethany Acker George Joseph Fulbrook Dorothy Elizabeth 5/4/1935 Batavia Ackerman Charles Marshall Brumsted Isabel Sara 9/7/1917 Batavia Ackerson Elmer Schwartz Elizabeth M. 2/26/1908Le Roy Ackerson Glen D. Mills Marjorie E. 02/06/1913 Oakfield Ackerson Raymond George Sherman Eleanora E. Amelia 10/25/1927 Batavia Ackert Daniel H. Fisher Catherine M. 08/08/1916 Oakfield Ackley Irving Amos Reid Elizabeth Helen 03/17/1926 Le Roy Acquisto Paul V. Happ Elsie L. 8/27/1925Niagara Falls, Niagara Co. Acton Robert Edward Derr Faith Emma 6/14/1913Brockport, Monroe Co. Adamowicz Ian Kizewicz Joseta 5/14/1917Batavia Adams Charles F. Morton Blanche C. 4/30/1908Le Roy Adams Edward Vice Jane 4/20/1908Batavia Adams Edward Albert Considine Mary 4/6/1920Batavia Adams Elmer Burrows Elsie M. 6/6/1911East Pembroke Adams Frank Leslie Miller Myrtle M. 02/22/1922 Brockport, Monroe Co. Adams George Lester Rebman Florence Evelyn 10/21/1926 Corfu Adams John Benjamin Ford Ada Edith 5/19/1920Batavia Adams Joseph Lawrence Fulton Mary Isabel 5/21/1927Batavia Adams Lawrence Leonard Boyd Amy Lillian 03/02/1918 Le Roy Adams Newton B.