Central Eurasia 2008

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Dossier Spécial Dossier S P É C I

g l o m e d . f r e e . f r / l a p r i n c i p a u t e . h t m l Le premier journal d’actualité de Monaco Juillet-Août 2008 Année VIII • Numéro 6 4 • Mensuel édité par Global Media Associates Sas • Gérant de la publication Roberto Numéro de Commission Paritaire : 0512 U 81608 • Dépôt légal : à parution • Imprimé sur papier spécial en Volponi • Rédaction et administration : “Le Beausoleil de Monaco” 6, boulevard de la Turbie 06240 Beausoleil Union Européenne • Concessionnaire général de publicité : Global Media Associates Sas - • Tél. : +33 09.50.79.90.84 • Fax (+33) 09.55.79.90.84 • Siège Social : Piazza Caduti della Montagnola 48 Section Publicité • Abonnements : annuel (soit 11 numéros) ≠ 20 ; hors Monaco et France +50% 00142 Rome • Tél./Fax (+39) 06.23.31.52.15 • Bureau de Milan : Tél./Fax (+39) 02.70.03.01.42 • S’adresser à Global Media Associates - Bureau Abonnements ou à http://glomed.free.fr/abo.pdf €2. 0 0 Dossier SS pp éé cc ii a l RReeiinneess dd’’EEggyyppttee ......eett EEggyyppttee ddeess RReeiinneess !! AA ll’’ooccccaassiioonn ddee llaa ggrraannddee eexxppoossiittiioonn ddee ll’’ééttéé aauu GGrriimmaallddii FFoorruumm,, rreeppoorrttaaggee eexxcclluussiiff ssuurr lleess lliieeuuxx ddee cceettttee aanncciieennnnee cciivviilliissaattiioonn ☞ UNE SOLUTION POUR L’ ACCESSION A LA PROPRIETE : VERS UN PATRIMOINE IMMOBILIER FAMILIAL ? • PAG E 8 2 La P r i n c i p a u t é D o s s i e r S p é c i a l Juillet-Août 2008 REPORTAGE EXCLUSIF • Voyage sur les lieux d’origine des pièces qui seront présentées lors de la grande Dossier SS pp éé c i a l Passion d’Egypte ! D’Abou Simbel à Alexandrie, en passant par Louxor jusqu’au Caire : à travers N O T R E RE P O RTA G E EX C L U S I F epuis désormais quelques Patrice Zehr face à la bibiothéque d'Alexandrie du tombeau de Cléopâtre. -

Subbuteo.No.10.Pdf

ПРАВИЛА ДЛЯ АВТОРОВ (Tomialojc 1990)», либо «по сообщению В.А.Лысенко (1988) и Л.Томялойца (Tomialojc, 1990), данный вид 1) В бюллетене «Subbuteo» публикуются статьи и встречает-ся на осеннем пролете в Украине и Поль- краткие сообщения по всем проблемам орнитологии, ше». материалы полевых исследований, а также обзорные работы. Принимаются рукописи объемом до 10 стра- в списке литературы: ниц машинописи. Работы более крупного объема мо- книги: Паевский В.А. Демография птиц. — Л., 1985. гут быть приняты к опубликованию при специальном- –285 с. согласовании с редакционной коллегией. статьи: Ивановский И.И. Прошлое, настоящее и бу- 2) Статьи объемом более 1 стр. машинописи при- дущее сапсана в Беларуси // Труды Зоол. музея БГУ, т. нимаются только в электронном варианте. 1,–Минск, 1995. –с. 295–301. 3) Статьи и заметки объемом до 1 стр. принимают- тезисы: Самусенко И.Э. Аистообразные — эталон- ся либо в электронном, либо в машинописном вари- но-индикационная группа птиц // Материалы 10-й антах. Текст должен быть напечатан на белой бумаге Всесоюзн. орнитол. конф., ч. 2, кн. 2. — Минск, 1991. стандартного формата А4 (21 х 30 см) через 2 интерва- –с. 197–198. ла, не более 60 знаков в строке и 30 строк на странице. Редакция оставляет за собой право редактирова- Статьи, сообщения и заметки в рукописном вари- ния рукописей. Корректура иногородним авторам не анте принимаются только в виде исключения от орни- высылается. Возможно возвращение рукописей на тологов-любителей, студентов и учащихся. доработку. 4) Текст работы должен быть оформлен в следую- В одном номере бюллетеня публикуется, как пра- щем порядке: вило, не более двух работ одного автора. Исключение заглавие (заглавными буквами того же шрифта, что может быть сделано для работ в соавторстве. -

MINUTES CHIRPERSONS' COSAC in BRUSSELS

MINUTES OF THE MEETING OF THE CHAIRPERSONS OF COSAC Brussels, 5 July 2010 AGENDA: 1. Opening session • Welcome address by Mr Armand DE DECKER, Speaker of the Belgian Sénat • Adoption of the agenda of the meeting of the Chairpersons of COSAC and the draft agenda of the XLIV COSAC meeting • Procedural questions and miscellaneous matters 2. Priorities of the Belgian Presidency – guest speaker: Mr Olivier CHASTEL, State Secretary for European Affairs of Belgium 3. Relations between national Parliaments and the European Commission – guest speaker: Mr Maroš ŠEFČOVIČ, Vice-President of the European Commission in charge of Inter-Institutional Relations and Administration PROCEEDINGS: IN THE CHAIR: Mr Herman DE CROO, Co-Chairperson of the Federal Advisory Committee on European Affairs for the Belgian Chambre des représentants and Ms Vanessa MATZ, Co-Chairperson of the Federal Advisory Committee on European Affairs for the Belgian Sénat. 1. Opening session The meeting of the Chairpersons of COSAC organized by the Belgian Presidency was held on 5 July 2010 in the hemicycle of the Belgian Sénat in Brussels. The opening session was chaired by Mr Herman DE CROO. Welcome address by Mr Armand DE DECKER, Speaker of the Belgian Sénat Mr Armand DE DECKER, Speaker of the Belgian Sénat, welcomed the participants of the meeting, noting that for Belgium this was the twelfth Presidency of the EU. The Speaker extended special welcome to the delegation of the Icelandic Alþingi, which participated in the meeting of the Chairpersons of COSAC for the first time. The Speaker informed the Chairpersons that following the elections on 13 June 2010, the Belgian Federal Parliament would be reconstituted between 6 July 2010 (Chambre des représentants) and 20 July 2010 (Sénat). -

Freedom of Religion Or Belief in Georgia 2010-2019

FREEDOM OF RELIGION OR BELIEF IN GEORGIA Report 2010-2019 FREEDOM OF RELIGION OR BELIEF IN GEORGIA REPORT 2010-2019 Tolerance and Diversity Institute (TDI) 2020 The report is prepared by Tolerance and Diversity Institute (TDI) within the framework of East-West Management Institute’s (EWMI) "Promoting Rule of Law in Georgia" (PROLoG) project, funded by the United States Agency for International Development (USAID). The report is published with the support from the Open Society Georgia Foundation (OSGF). The content is the sole responsibility of the Tolerance and Diversity Institute (TDI) and does not necessarily reflect the views of the United States Agency for International Development (USAID), United States Government, East-West Management Institute (EWMI) or Open Society Georgia Foundation (OSGF). Authors: Mariam Gavtadze, Eka Chitanava, Anzor Khatiashvili, Mariam Jikia, Shota Tutberidze, Gvantsa Lomaia Project director: Mariam Gavtadze Translators: Natia Nadiradze, Tamar Kvaratskhelia Design: Tornike Lortkipanidze Cover: shutterstock It is prohibited to reprint, copy or distribute the material for commercial purposes without written consent of the Tolerance and Diversity Institute (TDI). Tolerance and Diversity Institute (TDI), 2020 Web: www.tdi.ge CONTENTS Introduction .............................................................................................................................................................. 8 Methodology ..........................................................................................................................................................10 -

Elaboration of Priority Components of the Transboundary Neman/Nemunas River Basin Management Plan (Key Findings)

Elaboration of Priority Components of the Transboundary Neman/Nemunas River Basin Management Plan (Key Findings) June 2018 Disclaimer: This report was prepared with the financial assistance of the European Union. The views expressed herein can in no way be taken to reflect the official opinion of the European Union. TABLE OF CONTENTS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ..................................................................................................................... 3 1 OVERVIEW OF THE NEMAN RIVER BASIN ON THE TERRITORY OF BELARUS ............................... 5 1.1 General description of the Neman River basin on the territory of Belarus .......................... 5 1.2 Description of the hydrographic network ............................................................................. 9 1.3 General description of land runoff changes and projections with account of climate change........................................................................................................................................ 11 2 IDENTIFICATION (DELINEATION) AND TYPOLOGY OF SURFACE WATER BODIES IN THE NEMAN RIVER BASIN ON THE TERRITORY OF BELARUS ............................................................................. 12 3 IDENTIFICATION (DELINEATION) AND MAPPING OF GROUNDWATER BODIES IN THE NEMAN RIVER BASIN ................................................................................................................................... 16 4 IDENTIFICATION OF SOURCES OF HEAVY IMPACT AND EFFECTS OF HUMAN ACTIVITY ON SURFACE WATER BODIES -

Review-Chronicle of Human Violations in Belarus in 2009

The Human Rights Center Viasna Review-Chronicle of Human Violations in Belarus in 2009 Minsk 2010 Contents A year of disappointed hopes ................................................................7 Review-Chronicle of Human Rights Violations in Belarus in January 2009....................................................................9 Freedom to peaceful assemblies .................................................................................10 Activities of security services .....................................................................................11 Freedom of association ...............................................................................................12 Freedom of information ..............................................................................................13 Harassment of civil and political activists ..................................................................14 Politically motivated criminal cases ...........................................................................14 Freedom of conscience ...............................................................................................15 Prisoners’ rights ..........................................................................................................16 Review-Chronicle of Human Rights Violations in Belarus in February 2009................................................................17 Politically motivated criminal cases ...........................................................................19 Harassment of -

Armenian Monuments Awareness Project

Armenian Monuments Awareness Project Armenian Monuments Awareness Project he Armenian Monuments Awareness Proj- ect fulfills a dream shared by a 12-person team that includes 10 local Armenians who make up our Non Governmental Organi- zation. Simply: We want to make the Ar- T menia we’ve come to love accessible to visitors and Armenian locals alike. Until AMAP began making installations of its infor- Monuments mation panels, there remained little on-site mate- rial at monuments. Limited information was typi- Awareness cally poorly displayed and most often inaccessible to visitors who spoke neither Russian nor Armenian. Bagratashen Project Over the past two years AMAP has been steadily Akhtala and aggressively upgrading the visitor experience Haghpat for local visitors as well as the growing thousands Sanahin Odzun of foreign tourists. Guests to Armenia’s popular his- Kobair toric and cultural destinations can now find large and artistically designed panels with significant information in five languages (Armenian, Russian, Gyumri Fioletovo Aghavnavank English, French, Italian). Information is also avail- Goshavank able in another six languages on laminated hand- Dilijan outs. Further, AMAP has put up color-coded direc- Sevanavank tional road signs directing drivers to the sites. Lchashen Norashen In 2009 we have produced more than 380 sources Noratuz of information, including panels, directional signs Amberd and placards at more than 40 locations nation- wide. Our Green Monuments campaign has plant- Lichk Gegard ed more than 400 trees and -

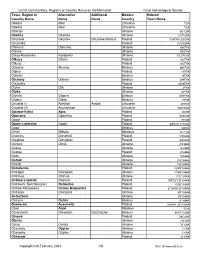

MVC All-Nameso-S.Xls

List of Communities, Regions or Country Name on the Memorial Israel Genealogical Society Town, Region or Alternative Additional Modern Hebrew Country Name Name Name Country Town Name אבל Obeliai Abel Lithuania אבל Obeliai Abel Lithuania אוברטין Obertyn Ukraine אוקוליצה Okolica Okolitsa Ukraine אוקוניב-מילוסנה Okuniew Okuniev Okuniew-Milosna Poland אוקונינקה Okuninka Poland אולנשט Olenesti Olenshat Ukraine אולבסק Olevsk Ukraine קורולובקה Oleyo-Korolevka Korolovka Ukraine אולקוש Olkusz Olkish Poland אולקוש Olkusz Poland אולימאן Ol'many Almany Belarus אלפיני Olpiny Poland אולשן Olshani Belarus אולשאן Olshany Olshan Belarus אולשנקה Olszanka Poland אוליק Olyka Olik Ukraine אוליקה Olyka Ukraine אולימלה Olymla Olypen Belarus אולפין Olypen Olpen Belarus אנישוק Onuskis (I) Anishok Ayskai Lithuania אנושישוק Onuskis (II) Anushishok Lithuania אפטא Opatow Kielci Apta Poland אופוצ'נה Opoczno Opochno Poland אופולה Opole Poland אופוליה לובלסקי Opole Lubelskie Opole Poland אופסה Opsa Belarus אורהיוב Orhei Orhaiv Moldava אושנציני Osieciny Osnetsini Poland אושיקוב Osjakow Oshyakov Poland אוסניצק Osnyck Osnik Ukraine אוסובא Osova Ukraine אוסובה Osowa Poland אוסטקי Ostki Ukraine אוסטראה Ostroh Ukraine אוסטראה Ostroh Ukraine אוסטרולנקה Ostrolenka Poland אוסטרופולה Ostropol Ostropola Ukraine אוסטריביה Ostrovye Ostrivia Ukraine אוסטרוב לובלסקי Ostrow Lubelski Ostrova Poland אוסטרובצה Ostrowiec Swietokrzyski Ostrovtse Poland אוסטרוב-משובייץ Ostrow-Mazowieca Ostrov Mazowiets Poland אוסטרוזץ Ostrozec Ostrozets Ukraine אוסטרוזץ Ostrozhets Ukraine אוסטרין Ostryna -

Beyond the Freakonomics of Religious Liberty

Changing Societies & Personalities, 2017 Vol. 1, No. 1 http://dx.doi.org/10.15826/csp.2017.1.1.003 Article Beyond the Freakonomics of Religious Liberty Ivan Strenski University of California, Riverside, USA ABSTRACT The paper critiques the prevailing liberal market economy models of religious liberty and religious encounter. In place of market models, this paper argues that values inscribed in gift exchange, hospitality, guest/host relations, in many cases, and to varying degrees, provide better alternative values to govern religious interaction than those of the market model. Instead of conceiving religion as commodity for “sale” – adoption, conversion – and instead of conceiving missionaries as salespeople for their religions, I propose that the encounter of religions could be better conceived in terms of guest/host, gift giver/gift receiver relations. “Freakonomics,” therefore, – whether in free market or monopoly form – does not, therefore, write the last page in the story of religious liberty. KEYWORDS Armenia, Freakonomics, guest/host, Holy Armenian Apostolic Church, liberty, market values, missionaries, religion. “Religious Liberty” as Commodity In May of 2013, I was invited to lecture in Armenia on religious liberty. Instead of teaching, I was “taken to school” about how West and East clashed over religious liberty. For Western governmental, religious and humanitarian groups, the values governing religious liberty or freedom were analogous to the values governing economic markets. The religious “marketplace” should be free and open to all competitors. Religious people should be free to make a “rational choice” of a religion. They should not be regulated in Received 15 January 2017 © 2017 Ivan Strenski Accepted 22 February 2017 [email protected] Published online 30 March 2017 28 Ivan Strenski making their fundamental religious decisions. -

Armenian Tourist Attraction

Armenian Tourist Attractions: Rediscover Armenia Guide http://mapy.mk.cvut.cz/data/Armenie-Armenia/all/Rediscover%20Arme... rediscover armenia guide armenia > tourism > rediscover armenia guide about cilicia | feedback | chat | © REDISCOVERING ARMENIA An Archaeological/Touristic Gazetteer and Map Set for the Historical Monuments of Armenia Brady Kiesling July 1999 Yerevan This document is for the benefit of all persons interested in Armenia; no restriction is placed on duplication for personal or professional use. The author would appreciate acknowledgment of the source of any substantial quotations from this work. 1 von 71 13.01.2009 23:05 Armenian Tourist Attractions: Rediscover Armenia Guide http://mapy.mk.cvut.cz/data/Armenie-Armenia/all/Rediscover%20Arme... REDISCOVERING ARMENIA Author’s Preface Sources and Methods Armenian Terms Useful for Getting Lost With Note on Monasteries (Vank) Bibliography EXPLORING ARAGATSOTN MARZ South from Ashtarak (Maps A, D) The South Slopes of Aragats (Map A) Climbing Mt. Aragats (Map A) North and West Around Aragats (Maps A, B) West/South from Talin (Map B) North from Ashtarak (Map A) EXPLORING ARARAT MARZ West of Yerevan (Maps C, D) South from Yerevan (Map C) To Ancient Dvin (Map C) Khor Virap and Artaxiasata (Map C Vedi and Eastward (Map C, inset) East from Yeraskh (Map C inset) St. Karapet Monastery* (Map C inset) EXPLORING ARMAVIR MARZ Echmiatsin and Environs (Map D) The Northeast Corner (Map D) Metsamor and Environs (Map D) Sardarapat and Ancient Armavir (Map D) Southwestern Armavir (advance permission -

Armenians in the Making of Modern Georgia

Armenians in the Making of Modern Georgia Timothy K. Blauvelt & Christofer Berglund While sharing a common ethnic heritage and national legacy, and an ambiguous status in relation to the Georgian state and ethnic majority, the Armenians in Georgia comprise not one, but several distinct communities with divergent outlooks, concerns, and degrees of assimilation. There are the urbanised Armenians of the capital city, Tbilisi (earlier called Tiflis), as well as the more agricultural circle of Armenians residing in the Javakheti region in southwestern Georgia.1 Notwithstanding their differences, these communities have both helped shape modern Armenian political and cultural identity, and still represent an intrinsic part of the societal fabric in Georgia. The Beginnings The ancient kingdoms of Greater Armenia encompassed parts of modern Georgia, and left an imprint on the area as far back as history has been recorded. Moreover, after the collapse of the independent Armenian kingdoms and principalities in the 4th century AD, some of their subjects migrated north to the Georgian kingdoms seeking save haven. Armenians and Georgians in the Caucasus existed in a boundary space between the Roman-Byzantine and Iranian cultures and, while borrowing from both spheres, struggled to preserve their autonomy. The Georgian regal Bagratids shared common origins with the Armenian Bagratuni dynasty. And as part of his campaign to forge a unified Georgian kingdom in the late 11th and early 12th centuries, the Georgian King David the Builder encouraged Armenian merchants to settle in Georgian towns. They primarily settled in Tiflis, once it was conquered from the Arabs, and in the town of Gori, which had been established specifically for Armenian settlers (Lordkipanidze 1974: 37). -

Review-Chronicle

REVIEW-CHRONICLE OF THE HUMAN RIGHTS VIOLATIONS IN BELARUS IN 1999 2 REVIEW-CHRONICLE OF THE HUMAN RIGHTS VIOLATIONS IN BELARUS IN 1999 INTRODUCTION: GENERAL CONCLUSIONS The year of 1999 was the last year of Alexander Lukashenka’s original mandate. In 1994 having used the machinery of democratic procedure he was elected president of the Republic of Belarus for five years term. But in 1996 A.Lukashenka conducted illegal, non-free and unfair referendum and by it prolonged his mandate to seven years. Constitutional Court’s judges and deputies of the Supreme Soviet that resisted to A.Lukashenka’s dictatorial intentions were dismissed. Thus provisions of the Constitution of the Republic of Belarus were broken. Attempt to conduct presidential elections done by the legitimate Supreme Soviet of the 13th convocation was supported by the most influential opposition parties and movements. But Belarusan authorities did their best to prevent opposition from succeeding in presidential elections and subjected people involved in election campaign to different kinds of repressions. Regime didn’t balk at anything in the struggle with its opponents. Detentions and arrests, persecutions of its organisers and participants, warnings, penalties and imprisonment followed every opposition-organised action… Yet the year of 1999 became a year of mass actions of protest of Belarusan people against a union with Russia imposed by the authorities to the people. In 1999 the OSCE Advisory and Monitoring Group in Belarus made an attempt to arrange talks between Belarusan authorities and opposition. This year will go down to history as a year when some of prominent politicians and fighters against the regime disappeared, when unprecedented number of criminal proceedings against opposition leaders and participants of mass actions of protest was instituted..