Part Ii Gold in West Borneo

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Sultans and Voivodas in the 16Th C. Gifts and Insignia*

SULTANS AND VOIVODAS IN THE 16TH C. GIFTS AND INSIGNIA* Prof. Dr. Maria Pia PEDANI** Abstract The territorial extent of the Ottoman Empire did not allow the central government to control all the country in the same way. To understand the kind of relations established between the Ottoman Empire and its vassal states scholars took into consideration also peace treaties (sulhnâme) and how these agreements changed in the course of time. The most ancient documents were capitulations (ahdnâme) with mutual oaths, derived from the idea of truce (hudna), such as those made with sovereign countries which bordered on the Empire. Little by little they changed and became imperial decrees (berat), which mean that the sultan was the lord and the others subordinate powers. In the Middle Ages bilateral agreements were used to make peace with European countries too, but, since the end of the 16th c., sultans began to issue berats to grant commercial facilities to distant countries, such as France or England. This meant that, at that time, they felt themselves superior to other rulers. On the contrary, in the 18th and 19th centuries, European countries became stronger and they succeeded in compelling the Ottoman Empire to issue capitulations, in the form of berat, on their behalf. The article hence deals with the Ottoman’s imperial authority up on the vassal states due to the historical evidences of sovereignty. Key Words: Ottoman Empire, voivoda, gift, insignia. 1. Introduction The territorial extent of the Ottoman Empire did not allow the central government to control all the country in the same way. -

Dress and Cultural Difference in Early Modern Europe European History Yearbook Jahrbuch Für Europäische Geschichte

Dress and Cultural Difference in Early Modern Europe European History Yearbook Jahrbuch für Europäische Geschichte Edited by Johannes Paulmann in cooperation with Markus Friedrich and Nick Stargardt Volume 20 Dress and Cultural Difference in Early Modern Europe Edited by Cornelia Aust, Denise Klein, and Thomas Weller Edited at Leibniz-Institut für Europäische Geschichte by Johannes Paulmann in cooperation with Markus Friedrich and Nick Stargardt Founding Editor: Heinz Duchhardt ISBN 978-3-11-063204-0 e-ISBN (PDF) 978-3-11-063594-2 e-ISBN (EPUB) 978-3-11-063238-5 ISSN 1616-6485 This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 04. International License. For details go to http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/. Library of Congress Control Number:2019944682 Bibliographic information published by the Deutsche Nationalbibliothek The Deutsche Nationalbibliothek lists this publication in the Deutsche Nationalbibliografie; detailed bibliographic data are available on the Internet at http://dnb.dnb.de. © 2019 Walter de Gruyter GmbH, Berlin/Boston The book is published in open access at www.degruyter.com. Typesetting: Integra Software Services Pvt. Ltd. Printing and Binding: CPI books GmbH, Leck Cover image: Eustaţie Altini: Portrait of a woman, 1813–1815 © National Museum of Art, Bucharest www.degruyter.com Contents Cornelia Aust, Denise Klein, and Thomas Weller Introduction 1 Gabriel Guarino “The Antipathy between French and Spaniards”: Dress, Gender, and Identity in the Court Society of Early Modern -

SARAWAK GOVERNMENT GAZETTE PART II Published by Authority

For Reference Only T H E SARAWAK GOVERNMENT GAZETTE PART II Published by Authority Vol. LXXI 25th July, 2016 No. 50 Swk. L. N. 204 THE ADMINISTRATIVE AREAS ORDINANCE THE ADMINISTRATIVE AREAS ORDER, 2016 (Made under section 3) In exercise of the powers conferred upon the Majlis Mesyuarat Kerajaan Negeri by section 3 of the Administrative Areas Ordinance [Cap. 34], the following Order has been made: Citation and commencement 1. This Order may be cited as the Administrative Areas Order, 2016, and shall be deemed to have come into force on the 1st day of August, 2015. Administrative Areas 2. Sarawak is divided into the divisions, districts and sub-districts specified and described in the Schedule. Revocation 3. The Administrative Areas Order, 2015 [Swk. L.N. 366/2015] is hereby revokedSarawak. Lawnet For Reference Only 26 SCHEDULE ADMINISTRATIVE AREAS KUCHING DIVISION (1) Kuching Division Area (Area=4,195 km² approximately) Commencing from a point on the coast approximately midway between Sungai Tambir Hulu and Sungai Tambir Haji Untong; thence bearing approximately 260º 00′ distance approximately 5.45 kilometres; thence bearing approximately 180º 00′ distance approximately 1.1 kilometres to the junction of Sungai Tanju and Loba Tanju; thence in southeasterly direction along Loba Tanju to its estuary with Batang Samarahan; thence upstream along mid Batang Samarahan for a distance approximately 5.0 kilometres; thence bearing approximately 180º 00′ distance approximately 1.8 kilometres to the midstream of Loba Batu Belat; thence in westerly direction along midstream of Loba Batu Belat to the mouth of Loba Gong; thence in southwesterly direction along the midstream of Loba Gong to a point on its confluence with Sungai Bayor; thence along the midstream of Sungai Bayor going downstream to a point at its confluence with Sungai Kuap; thence upstream along mid Sungai Kuap to a point at its confluence with Sungai Semengoh; thence upstream following the mid Sungai Semengoh to a point at the midstream of Sungai Semengoh and between the middle of survey peg nos. -

Panoramic Trails to the Golden Cone Square Nature and Culture Between Altdorf, Burgthann and Postbauer-Heng S 2 Altdorf Dörlbach Schwarzenbach Buch Postbauer-Heng S 3

Panoramic trails to the golden cone square Nature and culture between Altdorf, Burgthann and Postbauer-Heng S 2 Altdorf Dörlbach Schwarzenbach Buch Postbauer-Heng S 3 73 Foreword Walking tour Dear visitors, 6 km from the -Bahn station (suburban railway station) Postbauer-Heng to the 1.5 hours -Bahn station Oberferrieden The joint decision of the environmental and building committees of both municipalities Postbauer-Heng Coming from the direction of Nuremberg you first walk (district of Neumarkt i. d. OPf.) and Burgthann (district through the pedestrian underpass to the other side of the of Nuremberg Land) on March 29, 2011 gave the go- railway line. From there via the ramp downwards and fur- ahead for this outstanding and “cross-border” project. ther on the foot and cycle path towards the main road B 8. The citizens of this region at the foot of the mountains Walk on through the tunnel tube and pass the skateboard Brentenberg and Dillberg have already been deeply root- tracks until you reach a crossroad in front of the sports ed for many generations. Numerous family and cultural club. Now turn right and go upwards. Until you reach connections were the basis for the increasingly growing Buch you will find the signs 1 2 along the way. As cooperation in economic and local affairs which has you turn left at the edge of the forest and walk on the proved to be a success especially concerning the school meadow path above of the sports club please enjoy the cooperation. The border between the municipalities is wide view over the surrounding area. -

Colgate Palmolive List of Mills As of June 2018 (H1 2018) Direct

Colgate Palmolive List of Mills as of June 2018 (H1 2018) Direct Supplier Second Refiner First Refinery/Aggregator Information Load Port/ Refinery/Aggregator Address Province/ Direct Supplier Supplier Parent Company Refinery/Aggregator Name Mill Company Name Mill Name Country Latitude Longitude Location Location State AgroAmerica Agrocaribe Guatemala Agrocaribe S.A Extractora La Francia Guatemala Extractora Agroaceite Extractora Agroaceite Finca Pensilvania Aldea Los Encuentros, Coatepeque Quetzaltenango. Coatepeque Guatemala 14°33'19.1"N 92°00'20.3"W AgroAmerica Agrocaribe Guatemala Agrocaribe S.A Extractora del Atlantico Guatemala Extractora del Atlantico Extractora del Atlantico km276.5, carretera al Atlantico,Aldea Champona, Morales, izabal Izabal Guatemala 15°35'29.70"N 88°32'40.70"O AgroAmerica Agrocaribe Guatemala Agrocaribe S.A Extractora La Francia Guatemala Extractora La Francia Extractora La Francia km. 243, carretera al Atlantico,Aldea Buena Vista, Morales, izabal Izabal Guatemala 15°28'48.42"N 88°48'6.45" O Oleofinos Oleofinos Mexico Pasternak - - ASOCIACION AGROINDUSTRIAL DE PALMICULTORES DE SABA C.V.Asociacion (ASAPALSA) Agroindustrial de Palmicutores de Saba (ASAPALSA) ALDEA DE ORICA, SABA, COLON Colon HONDURAS 15.54505 -86.180154 Oleofinos Oleofinos Mexico Pasternak - - Cooperativa Agroindustrial de Productores de Palma AceiteraCoopeagropal R.L. (Coopeagropal El Robel R.L.) EL ROBLE, LAUREL, CORREDORES, PUNTARENAS, COSTA RICA Puntarenas Costa Rica 8.4358333 -82.94469444 Oleofinos Oleofinos Mexico Pasternak - - CORPORACIÓN -

Gold and Power in Ancient Costa Rica, Panama, and Colombia

This is an extract from: Gold and Power in Ancient Costa Rica, Panama, and Colombia Jeffrey Quilter and John W. Hoopes, Editors published by Dumbarton Oaks Research Library and Collection Washington, D.C. © 2003 Dumbarton Oaks Trustees for Harvard University Washington, D.C. Printed in the United States of America www.doaks.org/etexts.html The Seed of Life: The Symbolic Power of Gold-Copper Alloys and Metallurgical Transformations Ana María Falchetti re-Hispanic metallurgy of the Americas is known for its technical variety. Over a period of more than three thousand years, different techniques were adopted by vari- Pous Indian communities and adapted to their own cultures and beliefs. In the Central Andes, gold and silver were the predominant metals, while copper was used as a base material. Central Andeans developed an assortment of copper-based alloys. Smiths hammered copper into sheets that would later be used to create objects covered with thin coatings of gold and silver. In northern South America and the Central American isth- mus gold-copper alloys were particularly common.1 Copper metallurgy was also important in Western Mexico and farther north. Putting various local technological preferences aside, Amerindians used copper exten- sively as a base material. What then were the underlying concepts that governed the symbol- ism of copper, its combination with other metals, and particular technologies such as casting methods in Pre-Columbian Colombia, Panama, and Costa Rica? Studies of physical and chemical processes are essential to a scientific approach to met- allurgy, but for a fuller understanding, technologies should not be divorced from cultural contexts. -

The Demographic Profile and Sustainability Growth of the Bidayuh Population of Sarawak

International Journal of Academic Research in Business and Social Sciences Vol. 8 , No. 14, Special Issue: Transforming Community Towards a Sustainable and Globalized Society, 2018, E-ISSN: 2222-6990 © 2018 HRMARS The Demographic Profile and Sustainability Growth of the Bidayuh Population of Sarawak Lam Chee Kheung & Shahren Ahmad Zaidi Adruce To Link this Article: http://dx.doi.org/10.6007/IJARBSS/v8-i14/5028 DOI: 10.6007/IJARBSS/v8-i14/5028 Received: 06 Sept 2018, Revised: 22 Oct 2018, Accepted: 02 Dec 2018 Published Online: 23 Dec 2018 In-Text Citation: (Kheung & Adruce, 2018) To Cite this Article: Kheung, L. C., & Adruce, S. A. Z. (2018). The Demographic Profile and Sustainability Growth of the Bidayuh Population of Sarawak. International Journal of Academic Research in Business and Social Sciences, 8(14), 69–78. Copyright: © 2018 The Author(s) Published by Human Resource Management Academic Research Society (www.hrmars.com) This article is published under the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY 4.0) license. Anyone may reproduce, distribute, translate and create derivative works of this article (for both commercial and non-commercial purposes), subject to full attribution to the original publication and authors. The full terms of this license may be seen at: http://creativecommons.org/licences/by/4.0/legalcode Special Issue: Transforming Community Towards a Sustainable and Globalized Society, 2018, Pg. 69 - 78 http://hrmars.com/index.php/pages/detail/IJARBSS JOURNAL HOMEPAGE Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at http://hrmars.com/index.php/pages/detail/publication-ethics 69 International Journal of Academic Research in Business and Social Sciences Vol. -

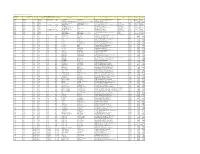

REMDP: Regional: Trans Borneo Power Grid: Sarawak to West

Trans Borneo Power Grid: Sarawak to West Kalimantan Transmission Link (RRP INO 44921) Draft Resettlement and Ethnic Minority Development Plan July 2011 REG: Trans Borneo Power Grid: Sarawak to West Kalimantan Link (Malaysia Section) Sarawak-West Kalimantan 275 kV Transmission Line Draft Resettlement and Ethnic Minority Development Plan (REMDP) July, 2011 Table of Contents I. Introduction ........................................................................................................................................... 1 II. Project Description ............................................................................................................................... 2 A. Project Location ............................................................................................................................... 2 B. Project Concept ................................................................................................................................ 2 C. REMDP Preparation and Efforts to Minimize Potential Resettlement Negative Impacts ................ 2 III. Scope of Land Acquisition and Resettlement ................................................................................... 4 A. Transmission Line Route ................................................................................................................. 4 1.Towers .......................................................................................................................................... 4 2.Auxiliary Installations.................................................................................................................... -

2016 N = Dewan Undangan Negeri (DUN) / State Constituencies

SARAWAK - 2016 N = Dewan Undangan Negeri (DUN) / State Constituencies KAWASAN / STATE PENYANDANG / INCUMBENT PARTI / PARTY N1 OPAR RANUM ANAK MINA BN-SUPP N2 TASIK BIRU DATO HENRY @ HARRY AK JINEP BN-SPDP N3 TANJUNG DATU ADENAN BIN SATEM BN-PBB N4 PANTAI DAMAI ABDUL RAHMAN BIN JUNAIDI BN-PBB N5 DEMAK LAUT HAZLAND BIN ABG HIPNI BN-PBB N6 TUPONG FAZZRUDIN ABDUL RAHMAN BN-PBB N7 SAMARIANG SHARIFAH HASIDAH BT SAYEED AMAN GHAZALI BN-PBB N8 SATOK ABG ABD RAHMAN ZOHARI BIN ABG OPENG BN-PBB N9 PADUNGAN WONG KING WEI DAP N10 PENDING VIOLET YONG WUI WUI DAP N11 BATU LINTANG SEE CHEE HOW PKR N12 KOTA SENTOSA CHONG CHIENG JEN DAP N13 BATU KITANG LO KHERE CHIANG BN-SUPP N14 BATU KAWAH DATUK DR SIM KUI HIAN BN-SUPP N15 ASAJAYA ABD. KARIM RAHMAN HAMZAH BN-PBB N16 MUARA TUANG DATUK IDRIS BUANG BN-PBB N17 STAKAN DATUK SERI MOHAMAD ALI MAHMUD BN-PBB N18 SEREMBU MIRO AK SIMUH BN N19 MAMBONG DATUK DR JERIP AK SUSIL BN-SUPP N20 TARAT ROLAND SAGEH WEE INN BN-PBB N21 TEBEDU DATUK SERI MICHAEL MANYIN AK JAWONG BN-PBB N22 KEDUP MACLAINE BEN @ MARTIN BEN BN-PBB N23 BUKIT SEMUJA JOHN AK ILUS BN-PBB N24 SADONG JAYA AIDEL BIN LARIWOO BN-PBB N25 SIMUNJAN AWLA BIN DRIS BN-PBB N26 GEDONG MOHD.NARODEN BIN MAJAIS BN-PBB N27 SEBUYAU JULAIHI BIN NARAWI BN-PBB N28 LINGGA SIMOI BINTI PERI BN-PBB N29 BETING MARO RAZAILI BIN HAJI GAPOR BN-PBB N30 BALAI RINGIN SNOWDAN LAWAN BN-PRS N31 BUKIT BEGUNAN DATUK MONG AK DAGANG BN-PRS N32 SIMANGGANG DATUK FRANCIS HARDEN AK HOLLIS BN-SUPP N33 ENGKILILI DR JOHNICAL RAYONG AK NGIPA BN-SUPP N34 BATANG AI MALCOM MUSSEN ANAK LAMOH BN-PRS N35 -

Laporan Keputusan Akhir Dewan Undangan Negeri Bagi Negeri Sarawak Tahun 2016

LAPORAN KEPUTUSAN AKHIR DEWAN UNDANGAN NEGERI BAGI NEGERI SARAWAK TAHUN 2016 BAHAGIAN PILIHAN RAYA NAMA CALON PARTI BILANGAN UNDI STATUS P.192-MAS GADING N.01 - OPAR RANUM ANAK MINA BN 3,665 MNG NIPONI ANAK UNDEK BEBAS 1,583 PATRICK ANEK UREN PBDSB 524 HD FRANCIS TERON KADAP ANAK NOYET PKR 1,549 JUMLAH PEMILIH : 9,714 KERTAS UNDI DITOLAK : 57 KERTAS UNDI DIKELUARKAN : 7,419 KERTAS UNDI TIDAK DIKEMBALIKAN : 41 PERATUSAN PENGUNDIAN : 76.40% MAJORITI : 2,082 BAHAGIAN PILIHAN RAYA NAMA CALON PARTI BILANGAN UNDI STATUS P.192-MAS GADING N.02 - TASIK BIRU MORDI ANAK BIMOL DAP 5,634 HENRY @ HARRY ANAK JINEP BN 6,922 MNG JUMLAH PEMILIH : 17,041 KERTAS UNDI DITOLAK : 197 KERTAS UNDI DIKELUARKAN : 12,797 KERTAS UNDI TIDAK DIKEMBALIKAN : 44 PERATUSAN PENGUNDIAN : 75.10% MAJORITI : 1,288 BAHAGIAN PILIHAN RAYA NAMA CALON PARTI BILANGAN UNDI STATUS P.193-SANTUBONG N.03 - TANJONG DATU ADENAN BIN SATEM BN 6,360 MNG JAZOLKIPLI BIN NUMAN PKR 468 HD JUMLAH PEMILIH : 9,899 KERTAS UNDI DITOLAK : 77 KERTAS UNDI DIKELUARKAN : 6,936 KERTAS UNDI TIDAK DIKEMBALIKAN : 31 PERATUSAN PENGUNDIAN : 70.10% MAJORITI : 5,892 PRU DUN Sarawak Ke-11 1 BAHAGIAN PILIHAN RAYA NAMA CALON PARTI BILANGAN UNDI STATUS P.193-SANTUBONG N.04 - PANTAI DAMAI ABDUL RAHMAN BIN JUNAIDI BN 10,918 MNG ZAINAL ABIDIN BIN YET PAS 1,658 JUMLAH PEMILIH : 18,409 KERTAS UNDI DITOLAK : 221 KERTAS UNDI DIKELUARKAN : 12,851 KERTAS UNDI TIDAK DIKEMBALIKAN : 54 PERATUSAN PENGUNDIAN : 69.80% MAJORITI : 9,260 BAHAGIAN PILIHAN RAYA NAMA CALON PARTI BILANGAN UNDI STATUS P.193-SANTUBONG N.05 - DEMAK LAUT HAZLAND -

The Illipe Nut (Shorea Spp.) As Additional Resource in Plantation Forestry

2013 The Illipe nut (Shorea spp.) as additional resource in plantation forestry Case Study in Sarawak, Malaysia Quirijn Coolen Van Hall Larenstein, University of Applied Sciences Bachelor Thesis 0 Student nr. 890102002 1 The Illipe nut (Shorea spp.) as additional resource in plantation forestry Case study in Sarawak, Malaysia Quirijn T. Coolen Bachelor Final Thesis 2013 Course: Tropical Forestry Student number: 890102002 January 1, 2014 Project supervisor Sarawak Forestry Department: Mr. Malcom Demies Cover photo: Nut, Shorea macrophylla (Connell, 1968) 2 “One, and only one incentive sends Sarawak Malay women deeply into the jungle. Not regularly, - but otherwise unique, is either one of two kinds of nut which fruit irregularly – but when they do in such profusion that every man, woman and child can usefully turn out to help reap these strictly “cash crops” in the coastal fringe.” (Harrisson & Salleh, 1960) 3 Acknowledgments I would like to acknowledge the support of the Van Hall Larenstein University, the Sarawak Forestry Department and the Sarawak Forestry Corporation for their approval and help on the completion of my Thesis study under their supervision. This report could not have been completed without the help of the following people in particular, to whom I want to express my greatest thanks; Dr. Peter van de Meer, who initiated the contact between the Sarawak Forestry Department and the Van Hall Larenstein University and was my personal supervisor from the latter, encouraging me to broaden my perspective on the subject and improve when necessary. Special thanks to my study and project partner, Jorn Dallinga, who traveled with me to Malaysia and with whom I shared the experience and work in the tropical Sarawak forests. -

Jkm Bagi Negeri Sarawak 2016 No.Telefon Negeri Daerah Bil Nama Kes Alamat Premis/ Rumah Projek Yang Diusahakan Pegawai Untuk Dihubungi

SENARAI PESERTA AKTIF DI BAWAH PROGRAM PENINGKATAN PENDAPATAN (2YEP) JKM BAGI NEGERI SARAWAK 2016 NO.TELEFON NEGERI DAERAH BIL NAMA KES ALAMAT PREMIS/ RUMAH PROJEK YANG DIUSAHAKAN PEGAWAI UNTUK DIHUBUNGI 014-8826530 KAMPUNG BANGKA SEMONG 94300 KOTA 1 WAN ZURIYAT BIN WAN MA'AD PERUSAHAAN TERNAKAN ITIK PENELUR SAMARAHAN 016-8819961 LORONG 10, KAMPUNG TANJUNG PARANG, PERNIAGAAN HASIL PERTANIAN (BUAH- 2 NORSHAFINAZ BINTI ABDULLAH 94600 KOTA SAMARAHAN BUAHAN & SAYURAN ) 013-8168042 LOT 3252 SUBLOT 267, JALAN DATUK MOD 3 PHANG CHING JAHITAN PAKAIAN MUSA, TAMAN IH HUNG FASA 2, SAMARAHAN SAMARAHAN 014-3934524 NO 36, KAMPUNG MELAYU, 94300 KOTA GERAI AIR MINUMAN,WALFFER DAN 4 ISMAWI BIN SUPERI SAMARAHAN KEREPEK RAZEMAH BINTI AZOOL TEL: 082-671191 014-5825332 NO 126, KAMPUNG MERANEK, 94300 KOTA 5 HANISAH BINTI ADENAN JAHITAN PAKAIAN WANITA DAN LELAKI SAMARAHAN 014-6965338 NO 124, LORONG ELORA, KAMPUNG MELAYU 6 HAMIMAH BINTI JOHARI PERNIAGAAN PASTRI SAMARAHAN 019-8981621 7 SERINAH BINTI EYONG KAMPUNG SERPAN LAUT, 94600 ASAJAYA JAHITAN PAKAIAN WANITA & LELAKI ASAJAYA 019-8148796 LOT 247, WISMA ASHA VILLA, KAMPUNG 8 JELIHA BINTI IDRIS GERAI MAKAN ASAJAYA ULU, 94600 ASAJAYA SARAWAK 014-5788456 RUSIK ANAK ENJO/ SERIAN 9 KASMA BOTTY BINTI ANIS KAMPUNG MELAYU TEBAKANG MENJUAL KUIH-MUIH TEL: 082-874070 019-4536306 MENGHIAS PELAMIN DAN MEMBUAT 10 FARIDAH BINTI MOHAMMAD KAMPUNG LOT HIJRAH, 94800 SIMUNJAN KUIH-MUIH DAN KEK RAZEMAH BINTI AZOOL SIMUNJAN 0162479175 TEL: 082-671191 11 ANUAR BIN JOHNY NO 313, KG HULU GEDONG, 94800 SIMUNJAN PERNIAGAAN CAFÉ CYBER