Aims, Selection Process and Criteria

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

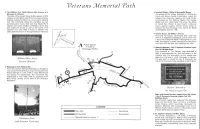

View a Copy of the Veterans Memorial Path Map (PDF)

te o 1. The Millburn Free Public Avenue, as a 3. Vauxhall Bridge - Battle of Marker Memorial to Veterans The plaque on the bridge, dedicated in 1928 by the The lobby of the present library facility, opened in 1976, Union and Essex County Freeholders, marks the contains an inscription taken from the previous library location that American regulars and local militia, building marking the library as a memorial to veterans commanded by Col. Mathias Ogden, Cpt. George from the community. Below the inscription are two Walker and Col. "Light Horse" Harry Lee, (the father commemorative books. One book lists World War II of famed Gen. Robert E. Lee) fought a delaying veterans who were residents of Millburn at the time action against superior British forces trying to they joined the service as well as the names of 14 outflank the main American force during the Battle residents who were killed in Korea or Vietnam. The of Springfield, June 23, 1780. other book lists donors to the original library memorial. 4. Hessian House, 155 Millburn Avenue This early farmhouse, constructed after 1730 from plans in A CarpE?rHer's Handbook, got its name from a story that during the Battle of Springfield in June, 1780, two Hessian soldiers deserted from the British army and hid in the attic, later settling in the area. Followapprox . 5 miles to 5. Veterans' Memorial R. Bosworth American Parsonage Hill Rd. Post 140, 200 Main Street This memorial to "The Veteran" was dedicated in 1985 to commemorate the 10th anniversary of the Vietnam War. The inscription on the plaque was taken from the nose of a U.S. -

The Blue Plaque Scheme

The Blue Plaque scheme Plaqu The first blue plaque programme started in Blue e he London in 1866 on the initiative of reformer f t William Ewart (1798-1869), supported by the o in Society of Arts. ig r o Did you know that the first erected blue plaque e commemorated one of Rochdale's most important figures? h T Lord George Gordon Byron, the poet, was an important figure for the town as he inherited the Manor of Rochdale in 1808 and was the last Byron to be Lord of the Manor of Rochdale until 1826. In 1867 a blue plaque was erected to commemorate Lord Byron at his birthplace, 24 Holles Street, Cavendish Square, London. Later in 1909, London City Council took the responsibility of the Blue Plaque Scheme. It played an important role in the preservation of the built heritage as it designed the round and blue plaques as we all know today. Over 800 plaques now celebrate the history of London. It was only in 1960 that Manchester erected its first commemorative plaque. Over 100 coloured plaques celebrate people, events of importance and buildings of special architectural and historic interest across the city. Look out for signs along the route to help you find your way. Our Vision Blue Plaque Map This Blue Plaque Map will take you on a journey Rochdale Town Centre through the town centre to discover its rich cultural history. This map shows the location of the 20 blue plaques erected up to the end of summer 2013, coupled with information on listed and historic buildings of great interest. -

Plaque Schemes Across England

PLAQUE SCHEMES ACROSS ENGLAND Plaque schemes are listed below according to region and county, apart from thematic schemes which have a national remit. The list includes: the name of the erecting body (with a hyperlink to a website where possible); a note of whether the scheme is active, dormant, proposed or complete; and a link to an email contact where available. While not all organisations give details of their plaques on their websites, the information included on the register should enable you to contact those responsible for a particular scheme. In a few cases, plaques are described as ‘orphaned’, which indicates that they are no longer actively managed or maintained by the organisation that erected them. English Heritage is not responsible for the content of external internet sites. BEDFORDSHIRE Bedford Borough ACTIVE Council Various historical schemes BEDFORDSHIRE Biggleswade COMPLETED Contact EAST History Society 1997-2004 BEDFORDSHIRE Dunstable COMPLETED Contact Town Council CAMBRIDGESHIRE Cambridge Blue ACTIVE Contact Plaques Scheme since 2001 CAMBRIDGESHIRE Eatons ACTIVE Contact Community Association 1 PLAQUE SCHEMES ACROSS ENGLAND CAMBRIDGESHIRE Great Shelford ACTIVE Contact Oral History Group CAMBRIDGESHIRE Littleport Society AD HOC One-off plaque erected in 2011, more hoped for. CAMBRIDGESHIRE Peterborough ACTIVE Contact Civic Society since the 1960s CAMBRIDGESHIRE St Ives ACTIVE Contact EAST Civic Society since 2008 CAMBRIDGESHIRE St Neots Local ACTIVE Contact History Society ESSEX (Basildon) PROPOSED Contact Foundation -

Blue Plaque Guide

Blue Plaque Guide Research and Cultural Collections 2 Blue Plaque Guide Foreword 3 Introduction 4 1 Dame Hilda Lloyd 6 2 Leon Abrams and Ray Lightwood 7 3 Sir Norman Haworth 8 4 Sir Peter Medawar 9 5 Charles Lapworth 10 6 Frederick Shotton 11 7 Sir Edward Elgar 12 8 Sir Granville Bantock 13 9 Otto Robert Frisch and Sir Rudolf E Peierls 14 10 John Randall and Harry Boot 15 11 Sir Mark Oliphant 16 12 John Henry Poynting 17 13 Margery Fry 18 14 Sir William Ashley 19 15 George Neville Watson 20 16 Louis MacNeice 21 17 Sir Nikolaus Pevsner 22 18 David Lodge 23 19 Francois Lafi tte 24 20 The Centre for Contemporary Cultural Studies 25 21 John Sutton Nettlefold 26 22 John Sinclair 27 23 Marie Corelli 28 Acknowledgments 29 Visit us 30 Map 31 Blue Plaque Guide 3 Foreword Across the main entrance to the Aston Webb Building, the historic centre of our campus, is a line of standing male figures carved into the fabric by Henry Pegram. If this were a cathedral, they would be saints or prophets; changed the world, from their common home the University but this is the University of Birmingham, and the people of Birmingham. who greet us as we pass through those doors are Beethoven, Virgil, Michelangelo, Plato, Shakespeare, The University’s Research and Cultural Collections, Newton, Watt, Faraday and Darwin. While only one of working with Special Collections, the Lapworth Museum, those (Shakespeare) was a local lad, and another (Watt) the Barber Institute of Fine Arts and Winterbourne House local by adoption, together they stand for the primacy of and Garden, reflect the cross-disciplinary nature of the creativity. -

Focus on Curiosity Pages 16 and 17

STAFF MAGAZINE | Michaelmas term 2017 Pages 16 and 17 Pages riosity Focus on Cu contributors index EDITORIAL TEAM 4 Day in the life of: Professor Louise Annette Cunningham Richardson Internal Communications Manager Public Affairs Directorate 6 So, you think you can’t dance? Dr Bronwyn Tarr discusses her Shaunna Latchman research Communications Officer (secondment) Public Affairs Directorate 8 News 11 My Oxford: Anne Laetitia Velia Trefethen Senior Graphic Designer Public Affairs Directorate 12 Team work: making Designer and Picture Researcher a great impression – Print Studio OTHER CONTRIBUTORS 14 Behind the hoardings – Beecroft Building 16 Curiosity Carnival: Rebecca Baxter the feedback Capital Projects Communications Manager Estates Services 18 CuriOXities – favourites from the University’s collections Meghan Lawson HR Officer (Policy & Communications) 20 Intermisson – staff Personnel Services activities outside of work 22 What’s on Caroline Moughton Staff Disability Advisor 24 My Family Care / Equality & Diversity Unit Disability support 25 Introduction to: Kevin Coutinho Matt Pickles Media Relations Manager 30 Perfection on a plate Public Affairs Directorate – enhancing your Christmas dinner experience Dan Selinger Head of Communications 31 Deck the halls – Academic Administration Division college festivities 2 Blueprint | Michaelmas term 2017 student Spotlight Amy Kerr, a second-year opportunity you’ve been given – The Moritz– undergraduate student, studying discussing legal issues with the academics Heyman Scholarship Law with Law Studies in Europe who wrote your textbook or who was made possible at Lady Margaret Hall, tells Dan administer the contracts for the University thanks to a Selinger about her experience is, well, rather cool. generous donation at Oxford. by Sir Michael How do your experiences Moritz and Ms Amy applied to Oxford after compare to your expectations Harriet Heyman. -

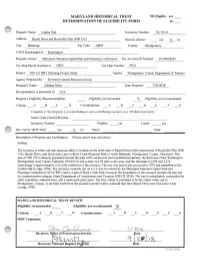

DETERMINATION 0F ELIGIBILITY FORM No

MARYLAND HISTORICAL TRUST NR Eligible: yes DETERMINATION 0F ELIGIBILITY FORM no Property Name: Linden oak inventory Number: M: 30-14 Address: Beach Drive and Roclrville pike (MD 355) Historic district: yes x no City: Bethesda Zip code: 20895 County : Montgomery USGS Quadrangle(s): Kensington Property owner: Maryland-National capital park and planning commission Tax Account lD Number: 07-00428301 Tax Map parcel Number(s): IIf23 TaxMapNumber: P914 Project: MD 355 BRT planning project study Ageney: Montgomery county Department of Transpo Agency prepared By: Dovetail cultural Resource Group Preparer's Nanie: Adriana Moss Date prepared: 7/20/2018 Documentation is presented in: N/A Preparer's Eligibility Recommendation: Eligibility recommended X Eligibility not recommended Criteria : A 8 C D Cons iderations : A 8 C D E F G Complete if the property is a contribwhng or non-contributing resource to a NR district/property: Name of the District/Property : Inventory Number: Eligible: yes Listed: yes SitevisitbyMHTstaff _ yes X no Name: Date: Desoription o£P[operty and lustifiicwion.. (Please attach map andphoto) Setting: The resource, a white oak tree (quercus alba), is located on the north side of Beach Drive at the intersection of Rockville Pike (MD 355), Beach Drive, and Grosvenor Lane in Rock Creek Regional Park in North Bethesda, Montgomery County, Maryland. This area of ho 355 is densely populated around the park with commercial and residential properties; the Red Line of the Washington Metropolitan Area Transit Authority (WMATA) rail system is 0.04 mile to the west, and the Interstate (I)-495 and I-270 interchange is approximately 0.25 mile southwest of the resource. -

The Georgia Courthouse Manual

The Georgia Courthouse Manual Georgia Department of Community Affairs Association County Commissioners of Georgia 1992 Edited and Published by the Georgia Department of Community Affairs Principal Author Jaeger/Pyburn, Inc., Gainesville, Georgia Project Funding Office of Historic Preservation, Georgia Department of Natural Resources Photographs: Page 13: Courtesy of Georgia Department of Archives and History, Vanishing Georgia Collection. Page 36 and page 37 (top) by Kay Morgareidge. Page 43 by Karen Oliver. Page 11 (bottom), page 17 (Emanuel and Wilkes), page 38, page 39 (bottom), page 42 (bottom), page 45, page 54 (bottom), and page 76 by Jaeger/Pyburn, Inc. Others by Georgia Department of Community Affairs. Drawings: Pages 12–14 by Ralph Avila. Pages 18–27 by Emmeline Embry. Others by Georgia Department of Community Affairs. This publication has been financed in part with Federal funds from the National Park Service, Department of the Interior, through the Office of Historic Preservation of the Georgia Department of Natural Resources. The contents and opinions do not necessarily reflect the views or policies of the Department of the Interior or the Georgia Department of Natural Resources, nor does the mention of trade names, commercial products or consultants constitute endorsement or recommendation by the Department of the Interior or the Georgia Department of Natural Resources. This program receives Federal financial assistance for identification and protection of historic properties. Under Title VI of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and Section 504 of the Rehabilitation Act of 1973, the U.S. Department of the Interior prohibits discrimination on the basis of race, color, national origin, or handicap in its federally assisted programs. -

Introduction

Introduction Robyn Magalit Rodriguez Filipinos have a history of presence and settlement in the United States that goes back several centuries. Every October, Filipino community-based as well as youth and student groups organize activities across the United States to cel- ebrate and commemorate that history. The month of October was designated “Filipino American History Month” by its originator, the Filipino American National Historical Society (fanhs), not only because it is the birth month of Filipino American labor leader, Larry Itliong1 (Itliong was born on October 25th), but because October 18, 1587 marks the first known landing of Filipinos on the shores of (what is now) the continental United States at Morro Bay, Cali- fornia. Filipinos at the time were Spanish colonial subjects and some com- prised the landing party of the Nuestra Señora de Buena Esperanza galleon. One Filipino American commentator notes that the landing was thirty-three years before the Pilgrims landed on Plymouth rock. This narrative along with the fact that groups like fanhs worked to ensure the marking of the site with a commemorative plaque and struggled for the recognition of Filipino American History Month more broadly are but a few examples of the kinds of invest- ments Filipino Americans have in staking a claim to Americanness and be- longing in America.2 Other historiographical and place-making practices and strategies that Fili- pino Americans engage in include texts like the now-classic, Filipinos: Forgot- ten Asian Americans by fahns founder Fred Cordova -

From the National Register of Historic Places Website for FAQ, September 26, 2016 How Do I Get a Plaque? Many Sites Listed in Th

From the National Register of Historic Places website for FAQ, September 26, 2016 How do I get a plaque? Many sites listed in the National Register arrange for a commemorative plaque. Unfortunately the National Register of Historic Places does not issue plaques as a result of listing; rather we leave it up to the individual owners if they are interested in having one. If you do not have a local trophy/plaque store that you prefer, we know of several companies that advertise in Preservation Magazine that offer the type of plaques that you may be interested in. We recommend that you contact your State historic preservation office to see if they have a preferred plaque style or wording. We are not endorsing, authorizing, recommending, or implying any connection to any one company over another, including any company not listed here. We are merely aware that these companies sell plaques. Properties listed in the National Register of Historic Places are not required to have plaques. All-Craft Wellman Products, Inc. 4839 East 345th Street Willoughby, OH 44094 www.all-craftwellman.com Phone: 800-340-3899 Fax: 440-946-9648 Arista Trophies & Awards 25 Portland Avenue Bergenfield, NJ 07621 p 201 387-2165 f 201 387-0955 http://www.aristatrophies.com/ Atlas Signs and Plaques Enterprise Drive Lake Mills, WI 53551 920-648-5647 http://www.atlassignsandplaques.com Artistic Bronze 13867 NORTHWEST 19TH AVENUE MIAMI, FLORIDA 33054 800.330.PLAK (7525) 305.681.2876 FAX http://www.artisticbronze.com/ Blue Pond Signs 4460 Redwood Hwy #9 San Rafael, CA 94903 Phone: (415) 507-0447 Fax: (415) 507-0451 http://www.bluepondsigns.com/custom-plaques.html Cerametallics a divison of Meridian Tile Products 101 S. -

Blue Plaques in Bromley

Blue Plaques in Bromley Blue Plaques in Bromley..................................................................................1 Alexander Muirhead (1848-1920) ....................................................................2 Benjamin Waterhouse Hawkins (1807-1889)...................................................3 Brass Crosby (1725-1793)...............................................................................4 Charles Keeping (1924-1988)..........................................................................5 Enid Blyton (1897-1968) ..................................................................................6 Ewan MacColl (1915-1989) .............................................................................7 Frank Bourne (1855-1945)...............................................................................8 Harold Bride (1890-1956) ................................................................................9 Heddle Nash (1895-1961)..............................................................................10 Little Tich (Harry Relph) (1867-1928).............................................................11 Lord Ted Willis (1918-1992)...........................................................................12 Prince Pyotr (Peter) Alekseyevich Kropotkin (1842-1921) .............................13 Richmal Crompton (1890-1969).....................................................................14 Sir Geraint Evans (1922-1992) ......................................................................15 Sir -

International Peace Gardens National Register Listing Date: Wednesday, March 26, 2014 2:37:48 PM

Memorandum Memorandum Planning Division Community & Economic Development Department To: Historic Landmark Commission From: Katia Pace, Principal Planner Date: March 26, 2014 Re: National Register of Historic Places Nomination: International Peace Gardens Attached please find the National Register of Historic Places nomination for the International Peace Gardens located at 1000 South 900 West. National Register The National Register of Historic Places is the official federal listing of cultural resources that are significant in American history, architecture, archaeology, and engineering. The Utah State Historic Preservation Office (SHPO) desires input from the Historic Landmark Commission, a Certified Local Government (CLG), regarding National Register nominations within the Salt Lake City’s boundaries. A nomination is reviewed by the State Historic Preservation Review Board prior to being submitted to the National Park Service, the federal organization responsible for the National Register. Listing on the National Register provides recognition and assists in preserving the Nation's heritage. Listing of a property provides recognition of its historic significance and assures protective review of federal projects that might adversely affect the character of the historic property. Listing in the National Register does not place limitations on the property by the federal or state government. Background The gardens comprise 11 acres and are located in Jordan Park along the banks of the Jordan River at 9th West and 10th South in Salt Lake. The garden was completed in 1947. Twenty-eight countries are represented at the gardens. The gardens are maintained by the Salt Lake City Parks Department. Criteria for Nomination The Peace Gardens are significant under the following National Register Criteria : Criteria A - The Gardens are significant in the areas of Ethnic Heritage and Social History in its reflection of a desire to increase cultural understanding prior to and following World War II. -

USG:1N President Ahidjo Visits the United States 3/13/62 16Mm, Color

USG:1N President Ahidjo Visits the United States 3/13/62 16mm, color, sof, "A" Wind, 372'- from first picture frame to tail sync mark. No head sync mark. Source: USIA, Received from Paul Fisher, White House, 9/18/64 Producer: Thomas Craven Film Corporation Productions This film covers the visit of President Ahmadou Ahidjo of the Cameroon to the United States. (Narrative throughout film.) Shot List 0'- First picture frame. 4'- Title sequence. 12'- President John F. Kennedy (JFK) and Diplomatic Corps welcome Ahidjo at Washington airport. 48'- JFK welcomes Ahidjo on behalf of the American people, and Ahidjo responds. 107'- Ahidjo arrives at the White House. JFK welcomes Ahidjo and other guests. 137'- Shots of JFK and Ahidjo in the White House with their respective advisors. 142'- Angier B. Duke, U.S. Chief of Protocol, shows Ahidjo Washington, D.C. Shots of the Capitol, Lincoln Memorial, and the Islamic Center. 190'- Diplomatic reception for Ahidjo. Shots of Mrs. Dean Rusk, and G. Mennen Williams, Asst. Sec. of State for African Affairs. 215'- Ahidjo visits New York City. Shots of Statue of Liberty and Ahidjo's motorcade through New York City. 257'- Ahidjo visits the UN. Shot of Acting Secretary-General U Thant. 284'- Ahidjo visits Long Island University, and receives honorary Doctor of Laws degree. 295'- Adlai Stevenson, US Ambassador to the UN, and Nelson Rockefeller, Gov. of N.Y., visit Ahidjo at the Hotel Waldorf Astoria. 315'- Mayor Robert F. Wagner and wife give reception for Ahidjo. Mayor Wagner of N.Y. gives gold medal and commemorative plaque to Ahidjo.