Memo for Motion

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Brief History of War Memorial Design

A BRIEF HISTORY OF WAR MEMORIAL DESIGN War Memorials in Manitoba: An Artistic Legacy A BRIEF HISTORY OF WAR MEMORIAL DESIGN war memorial may take many forms, though for most people the first thing that comes to mind is probably a freestanding monument, whether more sculptural (such as a human figure) or architectural (such as an arch or obelisk). AOther likely possibilities include buildings (functional—such as a community hall or even a hockey rink—or symbolic), institutions (such as a hospital or endowed nursing position), fountains or gardens. Today, in the 21st century West, we usually think of a war memorial as intended primarily to commemorate the sacrifice and memorialize the names of individuals who went to war (most often as combatants, but also as medical or other personnel), and particularly those who were injured or killed. We generally expect these memorials to include a list or lists of names, and the conflicts in which those remembered were involved—perhaps even individual battle sites. This is a comparatively modern phenomenon, however; the ancestors of this type of memorial were designed most often to celebrate a victory, and made no mention of individual sacrifice. Particularly recent is the notion that the names of the rank and file, and not just officers, should be set down for remembrance. A Brief History of War Memorial Design 1 War Memorials in Manitoba: An Artistic Legacy Ancient Precedents The war memorials familiar at first hand to Canadians are most likely those erected in the years after the end of the First World War. Their most well‐known distant ancestors came from ancient Rome, and many (though by no means all) 20th‐century monuments derive their basic forms from those of the ancient world. -

Needlepoint Kneeler Cushions Glenn Memorial United Methodist Church Remembering the Process: 2004-2008

Needlepoint Kneeler Cushions Glenn Memorial United Methodist Church Remembering the Process: 2004-2008 FOREWORD The Altar Guild extends heartfelt gratitude to the following individuals and businesses which were extremely generous and helpful to the completion of this project: Dr. David Jones, Senior Pastor, Glenn Memorial UMC The Glenn Memorial UMC Worship Committee, John Patton, Chairman Dr. Steven Darsey, Director of Music, Glenn Memorial UMC Nease’s Needlework Shop, Decatur, GA Corn Upholstery, Tucker, GA Carolyn Gilbert, Celebration dinner Genevieve Edwards, Editing booklet Dan Reed, Carpentry for new storage cabinet Nill Toulme, Photography Petite Auberge Restaurant, Toco Hills Shopping Center Betty Jo Copelan, Publication of booklet for Sunday service Nelia Butler, Sunday bulletin The dedicated women who stitched for months on end have given Glenn a magnificent gift that will enhance the life of the church for a long time. But it was Carole Adams who made this elaborate project work. As chairman of the kneeler committee she approached it with the drive and enthusiasm for the Glory of God that she has given to many other tasks of the church. For over four years she has brought together designer and stitchers at countless meetings- often at her own home, with refreshments. She has sent e-mails, raised funds, and driven miles to deliver supplies. Always helpful and encouraging, she has lovingly but firmly guided the needlepointers to the last perfect stitch… and has even found time to stitch a cushion herself. We salute Carole with -

West Sussex County Council Designation Full Report 19/09/2018

West Sussex County Council Designation Full Report 19/09/2018 Number of records: 36 Designated Memorials in West Sussex DesigUID: DWS846 Type: Listed Building Status: Active Preferred Ref NHLE UID Volume/Map/Item 297173 1027940 692, 1, 151 Name: 2 STREETLAMPS TO NORTH FLANKING WAR MEMORIAL Grade: II Date Assigned: 07/10/1974 Amended: Revoked: Legal Description 1. 5401 HIGH STREET (Centre Island) 2 streetlamps to north flanking War Memorial TQ 0107 1/151 II 2. Iron: cylindrical posts, fluted, with "Egyptian" capitals and fluted cross bars. Listing NGR: TQ0188107095 Curatorial Notes Type and date: STREET LAMP. Main material: iron Designating Organisation: DCMS Location Grid Reference: TQ 01883 07094 (point) Map sheet: TQ00NW Area (Ha): 0.00 Administrative Areas Civil Parish Arundel, Arun, West Sussex District Arun, West Sussex Postal Addresses High Street, Arundel, West Sussex, BN18 9AB Listed Building Addresses Statutory 2 STREETLAMPS TO NORTH FLANKING WAR MEMORIAL Sources List: Department for the Environment (now DCMS). c1946 onward. List of Buildings of Special Architectural or Historic Interest for Arun: Arundel, Bognor Regis, Littlehampton. Greenbacks. Web Site: English Heritage/Historic England. 2011. The National Heritage List for England. http://www.historicengland.org.uk/listing/the-list/. Associated Monuments MWS11305 Listed Building: 2 Streetlamps flanking the War Memorial, Arundel Additional Information LBSUID: 297173 List Locality: List Parish: ARUNDEL List District: ARUN List County: WEST SUSSEX Group Value: Upload Date: 28/03/2006 DesigUID: DWS8887 Type: Listed Building Status: Active Preferred Ref NHLE UID Volume/Map/Item 1449028 1449028 Name: Amberley War Memorial DesignationFullRpt Report generated by HBSMR from exeGesIS SDM Ltd Page 1 DesigUID: DWS8887 Name: Amberley War Memorial Grade: II Date Assigned: 24/08/2017 Amended: Revoked: Legal Description SUMMARY OF BUILDING First World War memorial granite cross, 1919, with later additions for Second World War. -

Re-Shaping a First World War Narrative : a Sculptural Memorialisation Inspired by the Letters and Diaries of One New Zealand

Copyright is owned by the Author of the thesis. Permission is given for a copy to be downloaded by an individual for the purpose of research and private study only. The thesis may not be reproduced elsewhere without the permission of the Author. Re-Shaping a First World War Narrative: A Sculptural Memorialisation Inspired by the Letters and Diaries of One New Zealand Soldier David Guerin 94114985 2020 A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Fine Arts Massey University, Wellington, New Zealand (Cover) Alfred Owen Wilkinson, On Active Service in the Great War, Volume 1 Anzac; Volume 2 France 1916–17; Volume 3 France, Flanders, Germany (Dunedin: Self-published/A.H. Reed, 1920; 1922; 1924). (Above) Alfred Owen Wilkinson, 2/1498, New Zealand Field Artillery, First New Zealand Expeditionary Force, 1915, left, & 1917, right. 2 Dedication Dedicated to: Alfred Owen Wilkinson, 1893 ̶ 1962, 2/1498, NZFA, 1NZEF; Alexander John McKay Manson, 11/1642, MC, MiD, 1895 ̶ 1975; John Guerin, 1889 ̶ 1918, 57069, Canterbury Regiment; and Christopher Michael Guerin, 1957 ̶ 2006; And all they stood for. Alfred Owen Wilkinson, On Active Service in the Great War, Volume 1 Anzac; Volume 2 France 1916–17; Volume 3 France, Flanders, Germany (Dunedin: Self-published/A.H. Reed, 1920; 1922; 1924). 3 Acknowledgements Distinguished Professor Sally J. Morgan and Professor Kingsley Baird, thesis supervisors, for their perseverance and perspicacity, their vigilance and, most of all, their patience. With gratitude and untold thanks. All my fellow PhD candidates and staff at Whiti o Rehua/School of Arts, and Toi Rauwhārangi/ College of Creative Arts, Te Kunenga ki Pūrehuroa o Pukeahu Whanganui-a- Tara/Massey University, Wellington, especially Jess Richards. -

In the United States Court of Appeals for the Fourth Circuit

Appeal: 15-2597 Doc: 41-1 Filed: 04/11/2016 Pg: 1 of 39 No. 15-2597 __________________________________________________________________ IN THE UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS FOR THE FOURTH CIRCUIT AMERICAN HUMANIST ASSOCIATION, ET AL., Plaintiffs-Appellants, v. MARYLAND-NATIONAL CAPITAL PARK AND PLANNING COMMISSION, Defendant-Appellee, & THE AMERICAN LEGION, ET AL., Intervenors/Defendants-Appellees. On Appeal from the United States District Court for the District of Maryland, Greenbelt Division, Deborah K. Chasanow, District Judge BRIEF FOR AMICI CURIAE SENATOR JOE MANCHIN AND REPRESENTATIVES DOUG COLLINS, VICKY HARTZLER, JODY HICE, EVAN JENKINS, JIM JORDAN, MARK MEADOWS, AND ALEX MOONEY IN SUPPORT OF APPELLEES AND AFFIRMANCE Charles J. Cooper David H. Thompson Howard C. Nielson, Jr. Haley N. Proctor COOPER & KIRK, PLLC 1523 New Hampshire Avenue, N.W. Washington, D.C. 20036 (202) 220-9600 (202) 220-9601 (fax) [email protected] April 11, 2016 Attorneys for Amici Curiae Appeal: 15-2597 Doc: 41-1 Filed: 04/11/2016 Pg: 2 of 39 TABLE OF CONTENTS Page TABLE OF AUTHORITIES .................................................................................... ii INTEREST OF AMICI .............................................................................................. 1 ARGUMENT ............................................................................................................. 2 I. THE ESTABLISHMENT CLAUSE DOES NOT PROHIBIT THE USE OF SYMBOLS WITH RELIGIOUS MEANING TO COMMEMORATE OUR NATION’S HISTORY AND TO REFLECT VALUES SHARED -

The Friends of St. George's Memorial Church, Ypres

The Friends of St. George’s Memorial Church, Ypres Registered with the Charities Commission No. 213282-L1 President: The Rt. Revd. The Bishop of Gibraltar in Europe Vice-President: Lord Astor of Hever, D.L. Chairman: Sir Edward M. Crofton, Bt Vice-Chairman: Dr. D.F. Gallagher, 32 Nursery Road, Rainham, Kent ME8 0BE Email: [email protected] Hon. Treasurer: W.L. Leetham, 69 Honey Hill, Blean, Whitstable, Kent CT5 3BP Email: [email protected] Hon. Investment Adviser: P. Birchall Hon. Secretary: M.A. McKeon, 63 Wendover Road, Egham, Surrey TW18 3DD Email: [email protected] Membership Secretary: Miss E. Speare, 32 Fulwood Walk, London SW19 6RB Email: [email protected] Hon. Minutes Secretary: Mrs Ash Frisby Newsletter: c/o The Honorary Vice-Chairman Life Members: John Sumner and Michael Derriman Chaplain: Vacant No. 103 NEWSLETTER July 2019 The Eton College Memorial Stone COPYRIGHT All items printed in this newsletter are copyright of the Friends of St. George’s Memorial Church, Ypres. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording or any information storage and retrieval system, without prior permission in writing from the Friends of St. George’s Memorial Church, Ypres. DATA PROTECTION We respect your right to privacy. Our data policy adheres to the principles of the General Data Protection Regulation and summarizes what personally identifiable information we may collect, and how we might use this information. This policy also describes other important topics relating to your privacy. Information about our visitors and/or Friends is kept confidentially for the use of St George’s Memorial Church and the Friends of St George’s Memorial Church. -

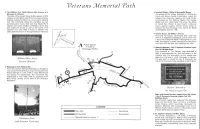

View a Copy of the Veterans Memorial Path Map (PDF)

te o 1. The Millburn Free Public Avenue, as a 3. Vauxhall Bridge - Battle of Marker Memorial to Veterans The plaque on the bridge, dedicated in 1928 by the The lobby of the present library facility, opened in 1976, Union and Essex County Freeholders, marks the contains an inscription taken from the previous library location that American regulars and local militia, building marking the library as a memorial to veterans commanded by Col. Mathias Ogden, Cpt. George from the community. Below the inscription are two Walker and Col. "Light Horse" Harry Lee, (the father commemorative books. One book lists World War II of famed Gen. Robert E. Lee) fought a delaying veterans who were residents of Millburn at the time action against superior British forces trying to they joined the service as well as the names of 14 outflank the main American force during the Battle residents who were killed in Korea or Vietnam. The of Springfield, June 23, 1780. other book lists donors to the original library memorial. 4. Hessian House, 155 Millburn Avenue This early farmhouse, constructed after 1730 from plans in A CarpE?rHer's Handbook, got its name from a story that during the Battle of Springfield in June, 1780, two Hessian soldiers deserted from the British army and hid in the attic, later settling in the area. Followapprox . 5 miles to 5. Veterans' Memorial R. Bosworth American Parsonage Hill Rd. Post 140, 200 Main Street This memorial to "The Veteran" was dedicated in 1985 to commemorate the 10th anniversary of the Vietnam War. The inscription on the plaque was taken from the nose of a U.S. -

Montage Fiches Rando

Leaflet Walks and hiking trails Haute-Somme and Poppy Country 8 Around the Thiepval Memorial (Autour du Mémorial de Thiepval) Peaceful today, this Time: 4 hours 30 corner of Picardy has become an essential Distance: 13.5 km stage in the Circuit of Route: challenging Remembrance. Leaving from: Car park of the Franco-British Interpretation Centre in Thiepval Thiepval, 41 km north- east of Amiens, 8 km north of Albert Abbeville Thiepval Albert Péronne Amiens n i z a Ham B . C Montdidier © 1 From the car park, head for the Bois d’Authuille. The carnage of 1st July 1916 church. At the crossroads, carry After the campsite, take the Over 58 000 victims in just straight on along the D151. path on your right and continue one day: such is the terrible Church of Saint-Martin with its as far as the village. Turn left toll of the confrontation war memorial built into its right- toward the D151. between the British 4th t Army and the German hand pillar. One of the many 3 Walk up the street opposite s 1st Army, fewer in number military pilgrimages to Poppy (Rue d’Ovillers) and keep going e r but deeply entrenched. Country, the emblematic flower as far as the crossroads. e Their machine guns mowed of the “Tommies”. By going left, you can cut t down the waves of infantrymen n At the cemetery, follow the lane back to Thiepval. i as they mounted attacks. to the left, ignoring adjacent Take the lane going right, go f Despite the disaster suffered paths, as far as the hamlet of through the Bois de la Haie and O by the British, the battle Saint-Pierre-Divion. -

History of the Hampstead War Memorial

Hampstead War Memorial Located on Main Street in the Center of Hampstead, Md. The War Memorial Association, in conjunction with the American Legion and the Rotary International have been instrumental in organizing the festivities for the dedication of the War Memorial in Hampstead. On November 1, 1947, dedication was held for the new War Memorial in front of the Hampstead High School on Main Street in Hampstead, Md. The dedication was very well attended and there were many speakers there. Among them were Senator Tydings, (who had just returned from making an extensive survey of the devastated and impoverished countries in Europe after the war), Former Mayor of Baltimore, Theodore R. McKelden, Samuel Jenness, superintendent of Carroll County Schools, Commanding officers or their alternates representing the Army, Navy, Marine and Coast Guard branches of the service, United States Senator George L. Radcliffer, Howard S. LeRoy, Governor of the 180th District of Rotary International, and Jack Tribby, State Adjutant of the American Legion. At this dedication, a bronze plaque was presented with 383 names of veterans from WWI and WWII and attached to the stone memorial wall. The $6,000 wall was built with funds collected by the War Memorial Association of Hampstead, The American Legion Post 200, and the local Rotary Club. Mr. George Bollinger, a stone mason laid the cornerstone as part of the ceremonies. The festivities opened to a crowd of about 500 people at 2 pm with a parade beginning at the south end of town, then came up to the north end of town and back down to the center of town in front of the school. -

Types of War Memorial

Types of war memorial On this sheet you will learn: make use of the natural environment that The different types of war memorial that have been dedicated as war memorials. exist in the UK. Often there will be information identifying Some typical features of war memorials the space as a war memorial, such as a Why war memorials vary so much. plaque or gates at the entrance. Photographs of different memorials can be Lychgates found in War Memorials Trust’s Gallery at www.learnaboutwarmemorials.org/youth- groups/gallery. Church fittings Church fittings include items such as bells, church organs or seating. These have often been chosen by communities as a way of remembering war casualties and may have a plaque or inscription Newton Regis memorial lychgate, © War Memorials Warwickshire identifying the object as a war memorial. A lychgate is a gate with a roof covering it, Crosses which stands at the entrance to a church. Lychgates that are war memorials will Some war memorial crosses are plain and often have the names of those simple with few additional features, while commemorated carved into the wooden others might be more elaborate, have a frame or roof, or be on plaques fixed to Celtic wheel cross design or additional the gate. Not all lychgates are war carvings. Crosses are often made of a type memorials but they were a popular choice of stone and may have a sword on it to after the First World War. show that it commemorates war. Monuments The term ‘monuments’ covers cenotaphs, obelisks, pillars and columns. These are large war memorials usually located in outdoor spaces, often in prominent places where they can be seen by lots of people. -

Last Post Indian War Memorials Around the World

Last Post Indian War Memorials Around the World Introduction • 1 Rana Chhina Last Post Indian War Memorials Around the World i Capt Suresh Sharma Last Post Indian War Memorials Around the World Rana T.S. Chhina Centre for Armed Forces Historical Research United Service Institution of India 2014 First published 2014 © United Service Institution of India All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without prior permission of the author / publisher. ISBN 978-81-902097-9-3 Centre for Armed Forces Historical Research United Service Institution of India Rao Tula Ram Marg, Post Bag No. 8, Vasant Vihar PO New Delhi 110057, India. email: [email protected] www.usiofindia.org Printed by Aegean Offset Printers, Gr. Noida, India. Capt Suresh Sharma Contents Foreword ix Introduction 1 Section I The Two World Wars 15 Memorials around the World 47 Section II The Wars since Independence 129 Memorials in India 161 Acknowledgements 206 Appendix A Indian War Dead WW-I & II: Details by CWGC Memorial 208 Appendix B CWGC Commitment Summary by Country 230 The Gift of India Is there ought you need that my hands hold? Rich gifts of raiment or grain or gold? Lo! I have flung to the East and the West Priceless treasures torn from my breast, and yielded the sons of my stricken womb to the drum-beats of duty, the sabers of doom. Gathered like pearls in their alien graves Silent they sleep by the Persian waves, scattered like shells on Egyptian sands, they lie with pale brows and brave, broken hands, strewn like blossoms mowed down by chance on the blood-brown meadows of Flanders and France. -

The Blue Plaque Scheme

The Blue Plaque scheme Plaqu The first blue plaque programme started in Blue e he London in 1866 on the initiative of reformer f t William Ewart (1798-1869), supported by the o in Society of Arts. ig r o Did you know that the first erected blue plaque e commemorated one of Rochdale's most important figures? h T Lord George Gordon Byron, the poet, was an important figure for the town as he inherited the Manor of Rochdale in 1808 and was the last Byron to be Lord of the Manor of Rochdale until 1826. In 1867 a blue plaque was erected to commemorate Lord Byron at his birthplace, 24 Holles Street, Cavendish Square, London. Later in 1909, London City Council took the responsibility of the Blue Plaque Scheme. It played an important role in the preservation of the built heritage as it designed the round and blue plaques as we all know today. Over 800 plaques now celebrate the history of London. It was only in 1960 that Manchester erected its first commemorative plaque. Over 100 coloured plaques celebrate people, events of importance and buildings of special architectural and historic interest across the city. Look out for signs along the route to help you find your way. Our Vision Blue Plaque Map This Blue Plaque Map will take you on a journey Rochdale Town Centre through the town centre to discover its rich cultural history. This map shows the location of the 20 blue plaques erected up to the end of summer 2013, coupled with information on listed and historic buildings of great interest.