American Theatre Design Since 1945

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Doctor Atomic

John Adams Doctor Atomic CONDUCTOR Opera in two acts Alan Gilbert Libretto by Peter Sellars, PRODUCTION adapted from original sources Penny Woolcock Saturday, November 8, 2008, 1:00–4:25pm SET DESIGNER Julian Crouch COSTUME DESIGNER New Production Catherine Zuber LIGHTING DESIGNER Brian MacDevitt CHOREOGRAPHER The production of Doctor Atomic was made Andrew Dawson possible by a generous gift from Agnes Varis VIDEO DESIGN and Karl Leichtman. Leo Warner & Mark Grimmer for Fifty Nine Productions Ltd. SOUND DESIGNER Mark Grey GENERAL MANAGER The commission of Doctor Atomic and the original San Peter Gelb Francisco Opera production were made possible by a generous gift from Roberta Bialek. MUSIC DIRECTOR James Levine Doctor Atomic is a co-production with English National Opera. 2008–09 Season The 8th Metropolitan Opera performance of John Adams’s Doctor Atomic Conductor Alan Gilbert in o r d e r o f v o c a l a p p e a r a n c e Edward Teller Richard Paul Fink J. Robert Oppenheimer Gerald Finley Robert Wilson Thomas Glenn Kitty Oppenheimer Sasha Cooke General Leslie Groves Eric Owens Frank Hubbard Earle Patriarco Captain James Nolan Roger Honeywell Pasqualita Meredith Arwady Saturday, November 8, 2008, 1:00–4:25pm This afternoon’s performance is being transmitted live in high definition to movie theaters worldwide. The Met: Live in HD series is made possible by a generous grant from the Neubauer Family Foundation. Additional support for this Live in HD transmission and subsequent broadcast on PBS is provided by the Alfred P. Sloan Foundation. Ken Howard/Metropolitan Opera Gerald Finley Chorus Master Donald Palumbo (foreground) as Musical Preparation Linda Hall, Howard Watkins, Caren Levine, J. -

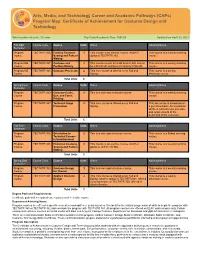

Program Map: Certificate of Achievement for Costume Design and Technology

Arts, Media, and Technology Career and Academic Pathways (CAPs) Program Map: Certificate of Achievement for Costume Design and Technology Total number of units: 23 units Top Code/Academic Plan: 1006.00 Updated on April 25, 2021 Fall Odd Course Code Course Units Notes Advising Notes Semester Program TECTHTR 366 Fantasy Costume 3 This course is an elective course. Another This course is a weekly morning Course Sewing and Pattern option is TECTHTR 365. course. Making Program/GE TECTHTR 367 Costume and 3 This course counts as a GE Area C Arts course This course is a weekly morning Course Fashion History for LACCD GE and Area C1 Arts for CSU GE. course. Program/GE TECTHTR 345 Costume Practicum 2 This core course is offered every Fall and This course is a weekly Course Spring. afternoon course. Total Units 8 Spring Even Course Code Course Units Notes Advising Notes Semester Program TECTHTR 363 Costume Crafts, 3 This is a core and milestone course. This course is a weekly morning Course Dye, and Fabric course. Printing Program TECTHTR 342 Technical Stage 2 This core course is offered every Fall and This lab course is scheduled on Course Production Spring. a per show basis. An orientation will be held to discuss schedule and requirements at the beginning of the semester. Total Units 5 Fall Even Course Code Course Units Notes Advising Notes Semester Program TECTHTR 305 Orientation to 2 This is a core and milestone course. This course is a Friday morning Course Technical Careers course. in Entertainment Program TECTHTR 365 Historical Costume 3 This course is an elective course. -

DISENCHANTING the AMERICAN DREAM the Interplay of Spatial and Social Mobility Through Narrative Dynamic in Fitzgerald, Steinbeck and Wolfe

DISENCHANTING THE AMERICAN DREAM The Interplay of Spatial and Social Mobility through Narrative Dynamic in Fitzgerald, Steinbeck and Wolfe Cleo Beth Theron Thesis presented in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree Master of Arts in the Faculty of Arts and Social Sciences at Stellenbosch University Supervisor: Dr. Dawid de Villiers March 2013 Stellenbosch University http://scholar.sun.ac.za ii DECLARATION By submitting this thesis/dissertation electronically, I declare that the entirety of the work contained therein is my own, original work, that I am the sole author thereof (save to the extent explicitly otherwise stated), that reproduction and publication thereof by Stellenbosch University will not infringe any third party rights and that I have not previously in its entirety or in part submitted it for obtaining any qualification. March 2013 Copyright © Stellenbosch University All rights reserved Stellenbosch University http://scholar.sun.ac.za iii ABSTRACT This thesis focuses on the long-established interrelation between spatial and social mobility in the American context, the result of the westward movement across the frontier that was seen as being attended by the promise of improving one’s social standing – the essence of the American Dream. The focal texts are F. Scott Fitzgerald’s The Great Gatsby (1925), John Steinbeck’s The Grapes of Wrath (1939) and Thomas Wolfe’s You Can’t Go Home Again (1940), journey narratives that all present geographical relocation as necessary for social progression. In discussing the novels’ depictions of the itinerant characters’ attempts at attaining the American Dream, my study draws on Peter Brooks’s theory of narrative dynamic, a theory which contends that the plotting operation is a dynamic one that propels the narrative forward toward resolution, eliciting meanings through temporal progression. -

01-11-2019 Porgy Eve.Indd

THE GERSHWINS’ porgy and bess By George Gershwin, DuBose and Dorothy Heyward, and Ira Gershwin conductor Opera in two acts David Robertson Saturday, January 11, 2020 production 7:30–10:50 PM James Robinson set designer New Production Michael Yeargan costume designer Catherine Zuber lighting designer The production of The Gershwins’ Porgy and Donald Holder Bess was made possible by a generous gift from projection designer Luke Halls The Sybil B. Harrington Endowment Fund and Douglas Dockery Thomas choreographer Camille A. Brown fight director David Leong general manager Peter Gelb Co-production of the Metropolitan Opera; jeanette lerman-neubauer Dutch National Opera, Amsterdam; and music director Yannick Nézet-Séguin English National Opera 2019–20 SEASON The 63rd Metropolitan Opera performance of THE GERSHWINS’ porgy and bess conductor David Robertson in order of vocal appearance cl ar a a detective Janai Brugger Grant Neale mingo lily Errin Duane Brooks Tichina Vaughn* sportin’ life a policeman Frederick Ballentine Bobby Mittelstadt jake an undertaker Donovan Singletary* Damien Geter serena annie Latonia Moore Chanáe Curtis robbins “l aw yer” fr a zier Chauncey Packer Arthur Woodley jim nel son Norman Garrett Jonathan Tuzo peter str awberry woman Jamez McCorkle Aundi Marie Moore maria cr ab man Denyce Graves Chauncey Packer porgy a coroner Kevin Short Michael Lewis crown scipio Alfred Walker* Neo Randall bess Angel Blue Saturday, January 11, 2020, 7:30–10:50PM The worldwide copyrights in the works of George Gershwin and Ira Gershwin for this presentation are licensed by the Gershwin family. GERSHWIN is a registered trademark of Gershwin Enterprises. Porgy and Bess is a registered trademark of Porgy and Bess Enterprises. -

Whole Document

Copyright By Christin Essin Yannacci 2006 The Dissertation Committee for Christin Essin Yannacci certifies that this is the approved version of the following dissertation: Landscapes of American Modernity: A Cultural History of Theatrical Design, 1912-1951 Committee: _______________________________ Charlotte Canning, Supervisor _______________________________ Jill Dolan _______________________________ Stacy Wolf _______________________________ Linda Henderson _______________________________ Arnold Aronson Landscapes of American Modernity: A Cultural History of Theatrical Design, 1912-1951 by Christin Essin Yannacci, B.A.; M.A. Dissertation Presented to the faculty of the Graduate School of The University of Texas at Austin in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy The University of Texas at Austin December, 2006 Acknowledgements There are many individuals to whom I am grateful for navigating me through the processes of this dissertation, from the start of my graduate course work to the various stages of research, writing, and editing. First, I would like to acknowledge the support of my committee members. I appreciate Dr. Arnold Aronson’s advice on conference papers exploring my early research; his theoretically engaged scholarship on scenography also provided inspiration for this project. Dr. Linda Henderson took an early interest in my research, helping me uncover the interdisciplinary connections between theatre and art history. Dr. Jill Dolan and Dr. Stacy Wolf provided exceptional mentorship throughout my course work, stimulating my interest in the theoretical and historical complexities of performance scholarship; I have also appreciated their insights and generous feedback on beginning research drafts. Finally, I have been most fortunate to work with my supervisor Dr. Charlotte Canning. From seminar papers to the final drafts of this project, her patience, humor, honesty, and overall excellence as an editor has pushed me to explore the cultural implications of my research and produce better scholarship. -

THTR 433A/ '16 CD II/ Syllabus-9.Pages

USCSchool of Costume Design II: THTR 433A Thurs. 2:00-4:50 Dramatic Arts Fall 2016 Location: Light Lab/PDE Instructor: Terry Ann Gordon Office: [email protected]/ floating office Office Hours: Thurs. 1:00-2:00: by appt/24 hr notice Contact Info: [email protected], 818-636-2729 Course Description and Overview This course is designed to acquaint students with the requirements, process and expectations for Film/TV Costume Designers, supervisors and crew. Emphasis will be placed on all aspects of the Costume process; Design, Prep: script analysis,“scene breakdown”, continuity, research, and budgeting; Shooting schedules, and wrap. The supporting/ancillary Costume Arts and Crafts will also be discussed. Students will gain an historical overview, researching a variety of designers processes, aesthetics and philosophies. Viewing films and film clips will support critique and class discussion. Projects focused on specific design styles and varied media will further support an overview of techniques and concepts. Current production procedures, vocabulary and technology will be covered. We will highlight those Production departments interacting closely with the Costume Department. Time permitting, extra-curricular programs will include rendering/drawing instruction, select field trips, and visiting TV/Film professionals. Students will be required to design a variety of projects structured to enhance their understanding of Film/TV production, concept, style and technique . Learning Objectives The course goal is for students to become familiar with the fundamentals of costume design for TV/Film. They will gain insight into the protocol and expectations required to succeed in this fast paced industry. We will touch on the multiple variations of production formats: Music Video, Tv: 4 camera vs episodic, Film, Commercials, Styling vs Costume Design. -

Text Pages Layout MCBEAN.Indd

Introduction The great photographer Angus McBean has stage performers of this era an enduring power been celebrated over the past fifty years chiefly that carried far beyond the confines of their for his romantic portraiture and playful use of playhouses. surrealism. There is some reason. He iconised Certainly, in a single session with a Yankee Vivien Leigh fully three years before she became Cleopatra in 1945, he transformed the image of Scarlett O’Hara and his most breathtaking image Stratford overnight, conjuring from the Prospero’s was adapted for her first appearance in Gone cell of his small Covent Garden studio the dazzle with the Wind. He lit the touchpaper for Audrey of the West End into the West Midlands. (It is Hepburn’s career when he picked her out of a significant that the then Shakespeare Memorial chorus line and half-buried her in a fake desert Theatre began transferring its productions to advertise sun-lotion. Moreover he so pleased to London shortly afterwards.) In succeeding The Beatles when they came to his studio that seasons, acknowledged since as the Stratford he went on to immortalise them on their first stage’s ‘renaissance’, his black-and-white magic LP cover as four mop-top gods smiling down continued to endow this rebirth with a glamour from a glass Olympus that was actually just a that was crucial in its further rise to not just stairwell in Soho. national but international pre-eminence. However, McBean (the name is pronounced Even as his photographs were created, to rhyme with thane) also revolutionised British McBean’s Shakespeare became ubiquitous. -

Christopher Plummer

Christopher Plummer "An actor should be a mystery," Christopher Plummer Introduction ........................................................................................ 3 Biography ................................................................................................................................. 4 Christopher Plummer and Elaine Taylor ............................................................................. 18 Christopher Plummer quotes ............................................................................................... 20 Filmography ........................................................................................................................... 32 Theatre .................................................................................................................................... 72 Christopher Plummer playing Shakespeare ....................................................................... 84 Awards and Honors ............................................................................................................... 95 Christopher Plummer Introduction Christopher Plummer, CC (born December 13, 1929) is a Canadian theatre, film and television actor and writer of his memoir In "Spite of Myself" (2008) In a career that spans over five decades and includes substantial roles in film, television, and theatre, Plummer is perhaps best known for the role of Captain Georg von Trapp in The Sound of Music. His most recent film roles include the Disney–Pixar 2009 film Up as Charles Muntz, -

GRAPHIC DESIGNER [email protected] +1(347)636.6681 AWARDS + HONORS SKILLS ASHLEY LAW EDUCATION WORK EXPERIENCE UNIQLO GLOBAL

ASHLEY LAW GRAPHIC DESIGNER [email protected] http://ashleylaw.info +1(347)636.6681 linkedin.com/in/ashley-law instagram.com/_ashleylaw EDUCATION AWA RDS SKILLS SCHOOL OF VISUAL + GRAPHIS (GOLD) SOFTWARE ARTS (New York) NEW TALENT ANNUAL InDesign HONORS BFA Design Editorial Design “Zine”- Illustrator 2017–2019 2018 Photoshop PremierePro AfterEffects SCHOOL OF THE SVA HONOR’S LIST Sketch ART INSTITUTE OF 2017–2018 CHICAGO (Chicago) Fine Art + Visual CAPABILITIES & Critical Studies SAIC MERIT Branding 2013–2015 SCHOLARSHIP Content Production 2013–2015 Identity System Interactive/Digital Design Print + Editorial Design Typography WORK EXPERIENCE UNIQLO GLOBAL Junior Graphic Design for the GCL team focusing on CREATIVE LAB Designer creative direction of special projects, 06. 2019 - Present (New York) under the direction of Shu Hung and John Jay. Campaigns include collaborations (i.e. Lemaire, JW Anderson, Alexander Wang) and new store openings. MATTE PROJECTS Design Intern Designing client proposals, print, 01. 2019–04. 2019 (New York) digital & social collateral for marketing agency. Worked on projects for Cartier, The Chainsmokers, Moda Operandi & MATTE events (FNT, BLACK-NYC, Full Moon Festival, La Luna). PYT OPERANDI Creative Project Associate for artist management & creative 03–06. 2016 Associate project development company with emphasis (Hong Kong) in film, photography, exhibitions, project & business development consulting. CLOVER GROUP Intimates Design Designed for leading global manufacturer INTL LIMITED. Intern of intimate apparel, emphasis on the 08–10. 2015 (Hong Kong) Victoria’s Secret account. Visually detailed creative direction, identity & design of project pitches. Similar work for clients including Wacoal, Aerie, Lane Bryant. GIORGIO ARMANI Menswear R&D Shadowed Manager of R&D department OPERATIONS Intern for Menswear at HK Armani Corporate 06–09. -

A Memory of Two Mondays (1955)

Boris Aronson: An Inventory of His Scenic Design Papers at the Harry Ransom Humanities Research Center Descriptive Summary Creator: Aronson, Boris, 1900-1980 Title: Boris Aronson Scenic Design Papers Dates: 1939-1977 Extent: 5 boxes, 4 oversize boxes, 47 oversize folders (4.1 linear feet) Abstract: Russian-born painter, sculptor, and most notably set designer Boris Aronson came to America in 1922. The Scenic Design Papers hold original sketches, prints, photographs, and technical drawings showcasing Aronson's set design work on thirty-one plays written and produced between 1939-1977. RLIN Record #: TXRC00-A6 Language: English. Access: Open for research Administrative Information Acquisition: Gift and purchase, 1996 (G10669, R13821) Processed by: Helen Baer and Toni Alfau, 1999 Repository: Harry Ransom Humanities Research Center, University of Texas at Austin Aronson, Boris, 1900-1980 Biographical Sketch Boris Aronson was born in Kiev in 1900, the son of a Jewish rabbi. He came of age in pre-revolutionary Russia in the city that was at the center of Jewish avant-garde theater. After attending art school in Kiev, Aronson served an apprenticeship with the Constructivist designer Alexandre Exter. Under Exter's tutelage and under the influence of the Russian theater directors Alexander Tairov and Vsevolod Meyerhold, whom Aronson admired, he rejected the fashionable realism of Stanislavski in favor of stylized reality and Constructivism. After his apprenticeship he moved to Moscow and then to Germany, where he published two books in 1922, and on their strength was able to obtain a visa to America. In New York he found work in the Yiddish experimental theater designing sets and costumes for, among other venues, the Unser Theatre and the Yiddish Art Theatre. -

Antje Ellermann Film Resume 02-24-20

ANTJE ELLERMANN Scene Design U.S.A. Local 829 c: 917 608-2243 e: [email protected] www.antjeellermann.com Film/ Television HBO MAX Gossip Girl Production Designer: Ola Maslik 2020 Assistant Art Director Art Director: Marissa Kotsilimbas Showtime Networks The President is Missing Production Designer: John Paino 2020 Scene Designer Supervising Art Director: Jordan Jacobs HBO The Plot Against America Production Designer: Richard Hoover 2019 Assistant Art Director Supervising Art Director: Jordan Jacobs Warner Bros. Television/ Fox Prodigal Son - Pilot Production Designer: Adam Scher 2019 Assistant Art Director Art Director: Deborah Wheatley Universal Cable Productions Happy! Season 2 Production Designer: Teresa Mastropierro 2018 Assistant Art Director Art Dir: Mylene Santos, Adrienne Carlyle NBC Universal The Village - Pilot Production Designer: Ola Maslik 2018 Assistant Art Director Art Director: Marissa Kotsilimbas NBC Universal Fashion Victim - Pilot Production Designer: Ola Maslik 2017 Assistant Art Director Art Director: Marissa Kotsilimbas Itv/ The Civilians This is Your Song! - Pilot Producer/ Director: Lynn Kestenbaum 2017 Art Director Writer/ Director: Steve Cosson NBC Universal The Wiz Live Production Designer: Derek McLane 2015 Assistant Art Director Art Director: Erica Hemminger NBC Universal Peter Pan Live Production Designer: Derek McLane 2014 Assistant Art Director Art Director: Aimee Bernadette Dombo 20th Century Fox Television Gotham - Pilot Production Designer: Naomi Shohan 2012 Assistant Art Director Art Director: -

Master Class with Monique Prudhomme: Selected Bibliography

Master Class with Monique Prudhomme: Selected Bibliography The Higher Learning staff curate digital resource packages to complement and offer further context to the topics and themes discussed during the various Higher Learning events held at TIFF Bell Lightbox. These filmographies, bibliographies, and additional resources include works directly related to guest speakers’ work and careers, and provide additional inspirations and topics to consider; these materials are meant to serve as a jumping-off point for further research. Please refer to the event video to see how topics and themes relate to the Higher Learning event. Film Costume Design (History and Theory) Annas, Alicia. “The Photogenic Formula: Hairstyles and Makeup in Historical Style.” in Hollywood and History: Costume Design in Film. Edward Maeder (ed). Los Angeles: Los Angeles County Museum of Art, 1987. 52-77. Chierichetti, David, and Edith Head. Edith Head: The Life and Times of Hollywood's Celebrated Designer. New York: Harper Collins Publishers, 2003. Coppola, Francis Ford, Eiko Ishioka, and Susan Dworkin. Coppola and Eiko on Bram Stoker's Dracula. San Francisco: Collins Publishers, 1992. Gutner, Howard. Gowns by Adrian: The MGM Years 1928-1941. New York: Harry N. Abrams, 2001. Jorgensen, Jay. Edith Head: The Fifty-Year Career of Hollywood's Greatest Costume Designer. Philadelphia: Running Press, 2010. Landis, Deborah N. Dressed: A Century of Hollywood Costume Design. New York: Collins Design, 2007. ---. Film Craft: Costume Design. New York: Focal Press, 2012. Laver, James, Amy De La Haye, and Andrew Tucker. Costume and Fashion: A Concise History. New York: Thames & Hudson, 2002. Leese, Elizabeth. Costume Design in the Movies: An Illustrated Guide to the Work of 157 Great Designers.