Japan's Road to Pluralism: Transforming Local Communities in the Global Era; (Ed

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

In This Issue

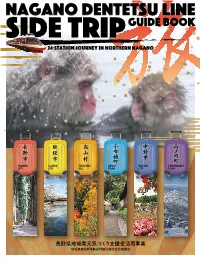

to Kanazawa In this issue to JoetsuJCT Toyoda-Iiyama I.C P.12 Nakano City Shinsyu-Nakano I.C P.14 Yudanaka Station Shinsyu-Nakano P.04 P.10 Station Nagano Yamanouchi Town Nagano City Obuse Town Snow Monkey Obuse Dentetsu Station Line Obuse P.A P.08 Suzaka Station Takayama Vill Nagano Zenkoji Temple Station P.06 Nagano I.C Expressway Suzaka City Nagano Expressway Joshinetsu Koshoku J.C.T Nagano Prefecture Nagano City Suzaka City Greetings from Northern 1Zenkoji × Soba× Oyaki p04 2 What´s Misosuki Don ? p06 Nagano! Come take a JoshinetsuExpressway Shinshu Matsumoto Airport Mathumoto I.C JR Hokuriku Shinkansen to Tokyo journey of 24 stations ! 02 Enjoy a scenic train ride through the 03 Nagano Hongo Kirihara Kamijyo Hino Kita-suzaka Entoku Nakano-Matsukawa Fuzokuchugakumae Murayama Shiyakushomae Shinano-Yoshida Suzaka Sakurasawa Shinsyu-Nakano Shinano-Takehara Gondo Obuse Zenkojishita Asahi Tsusumi Yomase Yudanaka Yanagihara Nagano countryside on the Nagano Dentetsu line. Nicknamed “Nagaden”, min 2 min 2 min 2 min 2 min 2 min 2 min 3 min 2 min 2 min 3 min 2 min 3 min 4 min 4 min 2 min 4 min 3 min 4 min 3 min 4 min 2 min 2 min 3 the train has linked Nagano City with Suzaka, Obuse, Nakano and Yamanouchi since it opened in 10- June, 1922. Local trains provide min 2 min 2 min 3 min 2 min 3 min 8 min 6 min 9 12min Limited B express leisurely service to all 24 stations min 2 14min min 6 min 9 12min along the way, while the express trains Limited A express such as the “Snow Monkey” reaches Takayama Village Obuse Town 【About express train 】 Yudanaka from Nagano Station in as quickly as 44 minutes. -

Niigata Port Tourist Information

Niigata Port Tourist Information http://www.mlit.go.jp/kankocho/cruise/ Niigata Sushi Zanmai Kiwami The Kiwami ("zenith") platter is a special 10-piece serving of the finest sushi, offered by participating establishments in Niigata. The platter includes local seasonal offerings unavailable anywhere else, together with uni (sea urchin roe), toro (medium-fat tuna), and ikura (salmon roe). The content varies according to the season and sea conditions, but you can always be sure you will be eating the best fish of the day. Location/View Access Season Year-round Welcome to Niigata City Travel Guide Related links https://www.nvcb.or.jp/travelguide/en/contents/food/index_f ood.html Contact Us[City of Niigata International Tourism Division ] TEL:+81-25-226-2614 l E-MAIL: [email protected] l Website: http://www.nvcb.or.jp/travelguide/en/ Tarekatsu Donburi A famous Niigata gourmet dish. It consists of a large bowl of rice(donburi) topped with a cutlet fried in breadcrumbs, cut into thin strips, and mixed with an exotic sweet and sour sauce. Location/View Access Season Year-round Welcome to Niigata City Travel Guide Related links https://www.nvcb.or.jp/travelguide/en/contents/food/index_f ood.html Contact Us[City of Niigata International Tourism Division ] TEL:+81-25-226-2614 l E-MAIL: [email protected] l Website: http://www.nvcb.or.jp/en/ Hegi-soba noodles "Hegi soba" is soba that is serviced on a wooden plate called "Hegi". It is made from seaweed called "funori" and you can enjoy a unique chewiness as well as the ease with whici it goes down your throat. -

Groundwater Oxygen Isotope Anomaly Before the M6.6 Tottori Earthquake

www.nature.com/scientificreports OPEN Groundwater oxygen isotope anomaly before the M6.6 Tottori earthquake in Southwest Japan Received: 13 December 2017 Satoki Onda1, Yuji Sano 1, Naoto Takahata 1, Takanori Kagoshima1, Toshihiro Miyajima1, Accepted: 8 March 2018 Tomo Shibata2, Daniele L. Pinti 3, Tefang Lan4, Nak Kyu Kim5, Minoru Kusakabe5 & Published: xx xx xxxx Yoshiro Nishio6 Geochemical monitoring of groundwater in seismically-active regions has been carried out since 1970s. Precursors were well documented, but often criticized for anecdotal or fragmentary signals, and for lacking a clear physico-chemical explanation for these anomalies. Here we report – as potential seismic precursor – oxygen isotopic ratio anomalies of +0.24‰ relative to the local background measured in groundwater, a few months before the Tottori earthquake (M 6.6) in Southwest Japan. Samples were deep groundwater located 5 km west of the epicenter, packed in bottles and distributed as drinking water between September 2015 and July 2017, a time frame which covers the pre- and post-event. Small but substantial increase of 0.07‰ was observed soon after the earthquake. Laboratory crushing experiments of aquifer rock aimed to simulating rock deformation under strain and tensile stresses were carried out. Measured helium degassing from the rock and 18O-shift suggest that the co-seismic oxygen anomalies are directly related to volumetric strain changes. The fndings provide a plausible physico- chemical basis to explain geochemical anomalies in water and may be useful in future earthquake prediction research. Hydro-geochemical precursors of major earthquakes have attracted the attention of researchers worldwide, because they are not entirely unexpected1,2. -

First Issuance of Green Bonds by Tokyo Gas

October 29, 2020 Tokyo Gas Co., Ltd. First Issuance of Green Bonds by Tokyo Gas Tokyo Gas Co., Ltd. (President: UCHIDA Takashi; “Tokyo Gas”) has decided to issue green bonds*1 (hereinafter the “issuance”) via a public offering platform, a first for the Company. Management plans a total issuance of ¥10 billion and is scheduling the issuance of 10-year bonds in December 2020. The capital to be procured from this issuance is slated to be allocated to the renewable energy project*2 the Tokyo Gas Group is participating in. The Tokyo Gas Group aims to contribute to the sustainable development of society. To this end, the group will continue to solve social issues through its business activities and thereby improve the group’s social and financial value to realize perpetual corporate management. *1: Bonds uses to finance projects with environmental improvement benefits *2: Press release for the renewable energy project to be financed through this issuance ・Acquisition of a solar power generation plant in Annaka, Gunma Prefecture (Japanese only) https://www.tokyo-gas.co.jp/Press/20200212-01.html ・Establishment of a Subsidiary in the United States and the Acquisition of a 500MW Solar Power Project https://www.tokyo-gas.co.jp/IR/english/library/pdf/tekijikaiji/20200729-04e.pdf [Green Bond profile] Maturity 10-year bond Total issuance ¥10.0 billion Issuance date December 2020 (tentative) Mitsubishi UFJ Morgan Stanley Securities Co., Ltd., Lead managers SMBC Nikko Securities Inc. Notification of other details will be released after they have been decided. [Determining green bond framework and acquisition of third-party assessment] In line with the issuance of green bonds, Tokyo Gas has formulated the Tokyo Gas Green Bond Framework*3 (hereinafter “framework) which specifies policies related to the four elements (1. -

Ffe

JP9950127 ®n m&?. mti HBA\ /j^¥ m** f «ffe#«i^p^fe«j:y f^± (top-soii) frbzarm (sub-son) '\<Dm$tm*wfeLtz0 i37 ,37 ®mmm(nmij\c£^ffi'Pi-& cs(DfrMim%¥mmmm7^mT\ ££>c cs<z)fe , i3, !^«££1ffiIELfc&JK0*£«fc^«'> tS Cs<Dn<Dffi8¥tmffil*4l~-42Spk%-3tz0 ffi^f.^CTi'N© 137Cs©*»4^iMf^±fc*)1.6~1.7%/^-C&o^o £fc* 1996^K t3, &\fZ Cs<Dft±£*<DTm<D%ttm&*mfeLfcm%\*¥ftX-6:4t1i-it:0 Residence half-time of 137Cs in the top-soils of Japanese paddy and upland fields Misako KOMAMURA, Akito TSUMURA*. Kiyoshi K0DA1RA** National Institute of Agro-Environmental Sciences, *ex-National Institute of Agro-Environmental Sciences, **Prof. Em. Ashikaga Institute of Technology A series of top-soil samples of 14 paddy fields and 10 upland fields in Japan, were annually collected during more than 30 years, to be examined in the contents of ,37Cs. The data, which were obtained by the use of a gamma spectrometric system, received some statistical treatments to distinguish the annual decline of 137Cs contents from deviations. Then the authors calculated "residence half-time of137Cs" within top-soil, and "eluviation rate of 137Cs" from top to the sub-layer of the soil. The following nationwide results were obtained irrespective of paddy or upland fields: (1) The "apparent residence half-time" was estimated as 16—-17 years. This one consists of both effects of eluviation and nuclear disintegration. (2) The "true residence half-time" was reported as 41~~42 years. This one depends on the eluviation speed of 137Cs exclusively, because the influence of nuclear disinte• gration has been compensated. -

Geography & Climate

Web Japan http://web-japan.org/ GEOGRAPHY AND CLIMATE A country of diverse topography and climate characterized by peninsulas and inlets and Geography offshore islands (like the Goto archipelago and the islands of Tsushima and Iki, which are part of that prefecture). There are also A Pacific Island Country accidented areas of the coast with many Japan is an island country forming an arc in inlets and steep cliffs caused by the the Pacific Ocean to the east of the Asian submersion of part of the former coastline due continent. The land comprises four large to changes in the Earth’s crust. islands named (in decreasing order of size) A warm ocean current known as the Honshu, Hokkaido, Kyushu, and Shikoku, Kuroshio (or Japan Current) flows together with many smaller islands. The northeastward along the southern part of the Pacific Ocean lies to the east while the Sea of Japanese archipelago, and a branch of it, Japan and the East China Sea separate known as the Tsushima Current, flows into Japan from the Asian continent. the Sea of Japan along the west side of the In terms of latitude, Japan coincides country. From the north, a cold current known approximately with the Mediterranean Sea as the Oyashio (or Chishima Current) flows and with the city of Los Angeles in North south along Japan’s east coast, and a branch America. Paris and London have latitudes of it, called the Liman Current, enters the Sea somewhat to the north of the northern tip of of Japan from the north. The mixing of these Hokkaido. -

Landslide Detection, Monitoring, Prediction, Emergency Measures and Technical Instruction in a Busy City, Atami, Japan

LANDSLIDE DETECTION, MONITORING, PREDICTION, EMERGENCY MEASURES AND TECHNICAL INSTRUCTION IN A BUSY CITY, ATAMI, JAPAN K. Fujisawa1, K. Higuchi1, A. Koda1 & T. Harada2 1 Public Works Research Institute, Japan (e-mail: [email protected]) 2 IST Co. Ltd., Japan (e-mail: [email protected]) Abstract: National highway No.135 is a main road that supports the regional economy and sightseeing spots in Izu Peninsula. Atami is a busy city and leading resort with many hotels and resort apartment buildings, attracting more than 8 million visitors every year. In late 2003/early 2004, warning phenomena appeared just before a landslide destroyed a slope along the highway. The road office administrators were concerned that the community would be seriously paralyzed if the landslide intercepted traffic and caused hotels and buildings to collapse. There had been several small landslides at the bottom of the slope in August and September, causing traffic jams and the successive rupture of water service pipes buried alongside the road. However, the administrators did not realize that the series of phenomena were caused by landslides. Two months later in November, a water service pipe ruptured again, and the road office finally investigated the slope. This time, a landslide scarp and cracks were found on the slope, and the administrators realized that the series of small August/September phenomena had been caused by a landslide 75 m long and 75 m wide. Monitoring of landslide activity by extensometers was quickly started, by which time the slide velocity had accelerated to more than 5 mm/day. On December 6, the sliding velocity reached 24.8 mm/day, and a landslide was predicted to occur at noon on January 5. -

Tokai Earthquake Preparedness in Shizuoka Prefecture, Japan

Tokai Earthquake Preparedness in Shizuoka Prefecture, Japan April 2010 Shizuoka Prefecture This document was originally created and published by Shizuoka Prefecture in Japan. English translation was provided by Yohko Igarashi, Visiting Scientist, ITIC, with the kind acceptance of Shizuoka Prefecture. For Educational and Non-Profit Use Only ! -,2#,21 1. Tokai Earthquake ዉዉዉዉዉዉዉዉዉዉዉዉዉዉዉዉዉዉዉዉዉዉዉዉዉዉዉዉዉዉዉዉዉዉዉዉዉዉዉዉ 1 (1) Tokai Earthquake ጟጟጟጟጟጟጟጟጟጟጟጟጟጟጟጟጟጟጟጟጟጟጟጟጟጟጟጟጟጟጟጟጟጟጟጟጟጟጟጟጟጟጟጟጟጟጟጟጟጟጟጟጟጟጟጟጟጟጟጟጟጟጟጟጟጟጟጟ 1 (2) Basis of the Occurrence of Tokai Earthquake ጟጟጟጟጟጟጟጟጟጟጟጟጟጟጟጟጟጟጟጟጟጟጟጟጟጟጟጟጟጟጟጟጟጟጟጟጟጟጟጟጟጟ 2 Fujikawa-kako Fault ZoneዋTonankaiNankai Earthquake ጟጟጟጟጟጟጟጟጟጟጟጟጟጟጟጟጟጟጟጟጟጟጟጟጟጟጟጟጟጟጟ 3 2. Estimated Damageዉዉዉዉዉዉዉዉዉዉዉዉዉዉዉዉዉዉዉዉዉዉዉዉዉዉዉዉዉዉዉዉዉዉዉዉዉዉዉዉ 4 3. Operation of Earthquake Preparedness ዉዉዉዉዉዉዉዉዉዉዉዉዉዉዉዉዉዉዉዉዉዉዉዉዉዉዉዉዉ 7 4. Monitoring System for Tokai Earthquake ዉዉዉዉዉዉዉዉዉዉዉዉዉዉዉዉዉዉዉዉዉዉዉዉዉዉዉ 10 (1) Governmental System of Earthquake Research ጟጟጟጟጟጟጟጟጟጟጟጟጟጟጟጟጟጟጟጟጟጟጟጟጟጟጟጟጟጟጟጟጟጟጟጟጟጟጟጟ 10 (2) Observation Network for Earthquake Prediction in Shizuoka Prefecture ጟጟጟጟጟጟጟጟጟጟጟጟጟጟጟጟጟ 11 5. Responses to the Issuance of “Information about Tokai Earthquake” ዉዉዉዉዉዉዉዉዉዉዉዉዉ 12 6. Working on Effective Disaster Managementዉዉዉዉዉዉዉዉዉዉዉዉዉዉዉዉዉዉዉዉዉዉዉዉዉዉ 14 (1) Disaster Management System in Shizuoka Prefecture ጟጟጟጟጟጟጟጟጟጟጟጟጟጟጟጟጟጟጟጟጟጟጟጟጟጟጟጟጟጟጟጟጟጟ 14 (2) Community Support Staffs in Local Disaster Prevention Bureau ጟጟጟጟጟጟጟጟጟጟጟጟጟጟጟጟጟጟጟጟጟጟጟጟ 14 (3) Establishing Permanent Disaster Management Headquarters Facilitiesጟጟጟጟጟጟጟጟጟጟጟጟጟጟጟጟጟጟጟ 15 (4) Advanced Information Network System ጟጟጟጟጟጟጟጟጟጟጟጟጟጟጟጟጟጟጟጟጟጟጟጟጟጟጟጟጟጟጟጟጟጟጟጟጟጟጟጟጟጟጟጟጟጟጟ -

Local Dishes Loved by the Nation

Sapporo 1 Hakodate 2 Japan 5 3 Niigata 6 4 Kanazawa 15 7 Sendai Kyoto 17 16 Kobe 10 9 18 20 31 11 8 ocal dishes Hiroshima 32 21 33 28 26 19 13 Fukuoka 34 25 12 35 23 22 14 40 37 27 24 29 Tokyo loved by 41 38 36 Nagoya 42 44 39 30 Shizuoka Yokohama 43 45 Osaka Nagasaki 46 Kochi the nation Kumamoto ■ Hokkaido ■ Tohoku Kagoshima L ■ Kanto ■ Chubu ■ Kansai 47 ■ Chugoku ■ Shikoku Naha ■ Kyushu ■ Okinawa 1 Hokkaido 17 Ishikawa Prefecture 33 Okayama Prefecture 2 Aomori Prefecture 18 Fukui Prefecture 34 Hiroshima Prefecture 3 Iwate Prefecture 19 Yamanashi Prefecture 35 Yamaguchi Prefecture 4 Miyagi Prefecture 20 Nagano Prefecture 36 Tokushima Prefecture 5 Akita Prefecture 21 Gifu Prefecture 37 Kagawa Prefecture 6 Yamagata Prefecture 22 Shizuoka Prefecture 38 Ehime Prefecture 7 Fukushima Prefecture 23 Aichi Prefecture 39 Kochi Prefecture 8 Ibaraki Prefecture 24 Mie Prefecture 40 Fukuoka Prefecture 9 Tochigi Prefecture 25 Shiga Prefecture 41 Saga Prefecture 10 Gunma Prefecture 26 Kyoto Prefecture 42 Nagasaki Prefecture 11 Saitama Prefecture 27 Osaka Prefecture 43 Kumamoto Prefecture 12 Chiba Prefecture 28 Hyogo Prefecture 44 Oita Prefecture 13 Tokyo 29 Nara Prefecture 45 Miyazaki Prefecture 14 Kanagawa Prefecture 30 Wakayama Prefecture 46 Kagoshima Prefecture 15 Niigata Prefecture 31 Tottori Prefecture 47 Okinawa Prefecture 16 Toyama Prefecture 32 Shimane Prefecture Local dishes loved by the nation Hokkaido Map No.1 Northern delights Iwate Map No.3 Cool noodles Hokkaido Rice bowl with Tohoku Uni-ikura-don sea urchin and Morioka Reimen Chilled noodles -

Local Cuisine Around Japan: Vol. 4 Hokkaido Genghis Khan from Hokkaido

Japan Local Government Centre (CLAIR, Sydney) This issue includes: 1 Local Cuisine around Japan 4 Vice Governor of Okayama visited Sydney 2 CLAIR Forum 2017 4 Article from Toowoomba: 2 The Kyushu Big Four at Matsuri Japan Festival Toowoomba Takatsuki Celebrating 25 years 3 Japan-Australia Tourism Seminar by JNTO 5 JETAA International Meeting in Tokyo 3 CLAIR Forum Magazine Interviews 7 From the Director Local Cuisine around Japan: Vol. 4 Hokkaido Genghis Khan from Hokkaido An island on its own, Hokkaido takes up nearly a quarter of the entire country. With its vast land and nature, Hokkaido is known to many tourists as a treasure trove of food, including seafood, agriculture, dairy products, wine, and sake. Of all the edible wonders this prefecture offers, there is one unique item that is not only popular among tourists, but is also a staple for locals: Genghis Khan. Genghis Khan is a lamb/mutton barbeque that uses uniquely-shaped skillets. One of the most common skillet shapes is that of a soldier’s helmet. The meat is grilled in the centre of the skillet, which rises in the middle like a mountain, and fresh local vegetables—common choices are bean sprouts, cabbage, onions, and pumpkin slices—are steamed on the rims with the juice that flows from the meat on top. Genghis Khan is often prepared in a cook-your-own style: diners grill the meat and vegetables by themselves, whether they are at home or in a restaurant. This makes Genghis Khan a great social opportunity as well, and even locals often go out to enjoy grilling up some Genghis Khan with glasses of local beer in hand. -

Monthly Glocal News

Monthly Glocal News December 2020 Local Partnership Cooperation Division Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Japan International exchange in Miyazaki Prefecture A tale of two pottery cities – — through the prefectural association in Brazil— Arita Town, Saga Prefecture in Japan and Meissen City in Germany – (Miyazaki Prefecture) The 35th anniversary ceremony of young The 70th anniversary ceremony of agriculturist dispatching program Miyazaki Kenjinkai Seven potters from Arita Town visited Dresden of he Miyazaki Kenjinkai (prefectural association) in former East Germany in 1970 Brazil is made up of those who have emigrated from Miyazaki prefecture to Brazil and their families. The association celebrated the 70th anniversary in 20T19. Miya zaki Prefecture has been interacting with Brazil for many years through the Kenjinkai, which acts as a bridge be- tween two sides. The members of the Kenjinkai think about Miyazaki far away from their hometown. The Prefecture al- so focuses on human exchanges of young generation between Brazil and Miyazaki including students and young people who are engaged in agriculture. Saraodori dance of Arita Town was performed in Meissen wine festival in 2019 Host Town Initiative in times of COVID19 – Even if we are far apart, our heart will always be together beyond the sea- (Kanagawa Prefecture and Fujisawa City) At the booths of cultural exchanges with citizen of Ambassador of the Republic of Online Meeting between Portu- Meissen in 2019 El Salvador to Japan presented coffee guese Paralympic athletes and beans to Kanagawa Prefecture and junior high school students in Fujisawa City (September 2020) Fujisawa City (October 2020) rita Town located in Saga Prefec- ture in Japan is known as the ujisawa City together with Kanagawa Prefecture will place where the first pottery was host the Tokyo 2020 Pre-Games Training Camps as a made within Japan. -

Nagano Regional

JTB-Affiliated Ryokan & Hotels Federation Focusing mainly on Nagano Prefecture Regional Map Nagano Prefecture, where the 1998 winter Olympics were held, is located in the center of Japan. It is connected to Tokyo in the southeast, Nagoya in the southwest, and also to Kyoto and Osaka. To the northeast you can get to Niigata, and to the northwest, you can get to Toyama and Kanazawa. It is extremely convenient to get to any major region of Japan by railroad, or highway bus. From here, you can visit all of the major sightseeing area, and enjoy your visit to Japan. Getting to Nagano Kanazawa Toyama JR Hokuriku Shinkansen Hakuba Iiyama JR Oito Line JR Hokuriku Line Nagano Ueda Karuizawa Limited Express () THUNDER BIRD JR Shinonoi Line JR Hokuriku Matsumoto Chino JR Chuo Line Shinkansen JR Chuo Line Shinjuku Shin-Osaka Kyoto Nagoya Tokyo Narita JR Tokaido Shinkansen O 二ニ〕 kansai Chubu Haneda On-line゜ Booking Hotel/Ryokan & Tour with information in Japan CLICK! CLICK! ~ ●JAPAN iCAN.com SUN 廊 E TOURS 四 ※All photos are images. ※The information in this pamphlet is current as of February 2019. ≫ JTB-Affiliated Ryokan & Hotels Federation ヽ ACCESS NAGANO ヽ Narita International Airport Osaka Haneda(Tokyo ダ(Kansai International International Airport) Airport) Nagoya Snow Monkey (Chubu Centrair The wild monkeys who seem to International Airport) enjoy bathing in the hot springs during the snowy season are enormously popular. Yamanouchi Town, Nagano Prefecture Kenrokuen This Japanese-style garden is Sado ga shima Niigata (Niigata Airport) a representative example of Nikko the Edo Period, with its beauty Niigata This dazzling shrine enshrines and grandeur.