Document Resume Abstract

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

United States Patent and Trademark Office

UNITED STATES PATENT AND TRADEMARK OFFICE TRADEMARK PUBLIC ADVISORY COMMITTEE MEETING Alexandria, Virginia Friday, February 11, 2011 2 1 PARTICIPANTS: 2 TPAC Members: 3 JOHN B. FARMER, Chair 4 JAMES G. CONLEY 5 MARY BONEY DENISON 6 TIMOTHY J. LOCKHART 7 KATHRYN B. PARK 8 DEBORAH HAMPTON 9 MAURY TEPPER 10 ANNE CHASSER 11 Union Members: 12 HOWARD FRIEDMAN 13 RANDALL P. MYERS 14 HAROLD E. ROSS 15 Also Present: 16 DEBORAH COHN, Commissioner 17 DANA ROBERT COLARULLI Director, Office of Government Affairs 18 ANTHONY P. SCARDINO ………………………………………..Chief Financial Officer 20 JOHN OWENS Chief Information Officer 21 GERARD ROGERS TTAB Chief Judge 22 3 1 PARTICIPANTS (CONT'D): 2 WILLIAM COVEY Office of Enrollment and Discipline 3 ………..CYNTHIA LYNCH Administrator for Examination Policy 4 HARRY I. MOATZ Office of Enrollment and Discipline 5 ERIK M. PELTON Erik M. Pelton and Associates 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 * * * * * 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 4 1 P R O C E E D I N G S 2 (9:00 a.m.) 3 CHAIRMAN FARMER: If everyone can take 4 their seats, please. I'd like to welcome 5 everybody to the TPAC meeting. My name is John 6 Farmer and I chair the committee. 7 I know this is old hat to perhaps 8 everybody in the room because I look around the 9 room and see so many familiar faces, but just in 10 case someone is new -- or for folks watching at 11 home -- this meeting is being webcast and it's 12 also being transcribed. -

Mitch Maclay Sings Just for You

MITCH MACLAY SINGS JUST FOR YOU A Play in One Act by Craig Bailey Craig Bailey 350 Woodbine Rd Shelburne VT 05482-6777 (802) 655-1197 ©2019 Craig Bailey [email protected] All rights reserved www.mitchmaclay.com CHARACTERS CHRISTOPHER WOOD Early-30s. Program Director and morning board operator for radio station TRU-92. HE capitalizes on the invisibility of his medium by dressing in casual clothing including baggy khakis, sneakers with no socks, and a comfortable T-shirt sporting the logo of an alternative band. His cynical attitude and occasionally snide veneer reflect the mind-set of an up-and- coming industry man who somehow made a wrong turn only to find himself, inexplicably, in rural Iowa. LORALIE KENT Early- to mid-20s. Evening board operator for TRU-92. SHE is dressed in simple slacks, blouse and stocking feet at rise -- with a fresh, natural, cheerful face that's wasted on the radio. Her eccentricity and inclination for seemingly pointless chatter disguise her high level of intelligence -- an asset that's thwarted only by her rose-colored naivete. SETTING Front office of radio station TRU-92 in a small Iowa town TIME A Saturday in the late-1980s 1. ACT I Scene 1 (The second story front office of radio station TRU-92 in a small Iowa town, late-1980s. The furnishings and decor are about 30 years behind the times. The overall atmosphere is drab, bordering on depressed. A doorway UC leads to a hallway. Entranceways DR and DL lead to the air studio and sales offices, respectively. -

Fall 2010 Voices 3

Fall 2010 VOICES UNIVERSITY OF HOUSTON LANGUAGE AND CULTURE CENTER 2 VOICES FALL 2010 Inside this issue: From the Director 3 Scholarship Winners 4 Our Life in the U.S. 5 About Me and My Country 6 Our Cultures, Our Values, and Our Assumptions 8 If I Were the Leader of My Country 11 Marriage Customs Around the World 12 Tourism 15 Education 16 Photos: Sports Tournament,, Class Trips, Halloween 17 The Texas Renaissance Festival 20 Cultural Adjustment 23 Sounds, Sights, and Smells from Our Childhood 24 What I Don’t Want to Lose 28 Funny Essays 30 Dave’s Page 32 The Culture Festival 35 FALL 2010 VOICES 3 From the Director Joy Tesh As the fall term of 2010 closes, the teachers, administrators, and support staff of the Language and Cul- ture Center wish you happy holidays and a safe and productive academic break from our program. The LCC office will be open through December 23, 2010, and then will close for the holidays and open again on January 3, 2011. We look forward to seeing many of you again in the new year. If you are leaving our program for any reason, we encourage you to stay in touch with us through email or through our web site. We love to hear from you. We are eager to hear from students who continue their studies at the University of Houston or at another school in the United States or who return to their countries to continue their journey. We have a great network of former LCC students all over the world. -

Leksykon Polskiej I Światowej Muzyki Elektronicznej

Piotr Mulawka Leksykon polskiej i światowej muzyki elektronicznej „Zrealizowano w ramach programu stypendialnego Ministra Kultury i Dziedzictwa Narodowego-Kultura w sieci” Wydawca: Piotr Mulawka [email protected] © 2020 Wszelkie prawa zastrzeżone ISBN 978-83-943331-4-0 2 Przedmowa Muzyka elektroniczna narodziła się w latach 50-tych XX wieku, a do jej powstania przyczyniły się zdobycze techniki z końca XIX wieku m.in. telefon- pierwsze urządzenie służące do przesyłania dźwięków na odległość (Aleksander Graham Bell), fonograf- pierwsze urządzenie zapisujące dźwięk (Thomas Alv Edison 1877), gramofon (Emile Berliner 1887). Jak podają źródła, w 1948 roku francuski badacz, kompozytor, akustyk Pierre Schaeffer (1910-1995) nagrał za pomocą mikrofonu dźwięki naturalne m.in. (śpiew ptaków, hałas uliczny, rozmowy) i próbował je przekształcać. Tak powstała muzyka nazwana konkretną (fr. musigue concrete). W tym samym roku wyemitował w radiu „Koncert szumów”. Jego najważniejszą kompozycją okazał się utwór pt. „Symphonie pour un homme seul” z 1950 roku. W kolejnych latach muzykę konkretną łączono z muzyką tradycyjną. Oto pionierzy tego eksperymentu: John Cage i Yannis Xenakis. Muzyka konkretna pojawiła się w kompozycji Rogera Watersa. Utwór ten trafił na ścieżkę dźwiękową do filmu „The Body” (1970). Grupa Beaver and Krause wprowadziła muzykę konkretną do utworu „Walking Green Algae Blues” z albumu „In A Wild Sanctuary” (1970), a zespół Pink Floyd w „Animals” (1977). Pierwsze próby tworzenia muzyki elektronicznej miały miejsce w Darmstadt (w Niemczech) na Międzynarodowych Kursach Nowej Muzyki w 1950 roku. W 1951 roku powstało pierwsze studio muzyki elektronicznej przy Rozgłośni Radia Zachodnioniemieckiego w Kolonii (NWDR- Nordwestdeutscher Rundfunk). Tu tworzyli: H. Eimert (Glockenspiel 1953), K. Stockhausen (Elektronische Studie I, II-1951-1954), H. -

Marquette Literary Review, Issue 7, Spring 2014

Spring 2014, Issue 7 Michele Furman, General Editor Erin McKay & Ivana Osmanovic, Poetry Editors Katie Murphy, Prose Editor Mary Cate Simone, Taylor Gall & Shannon Cassells, Assistant Editors Dr. Larry Watson, Consulting Adviser Marquette Literary Review ~ Spring 2014 Table of Contents: The Late Worm……………………………………………………………………………………………3 Katelyn Bishop Leroy Brown……………………………………………………………………………………………3 - 4 County Line Road, Indiana………………………………………………………………...…………4 - 6 N. Searles We Don't Even Have an Interstate Exit………………………………………………………………..6 Katelyn Bishop Lawyers Don’t Ride Buses………………………………………………………..……………….....7 - 8 Ghosts of Our Own Making……………………………………………………………………….….8 - 9 Unnecessary Roughness…………………………………………………………...……...……….…...9 Riptide………………………………………………..…………………………………………………....9 Erin McKay Untitled……….………………………………………………………………………………………...9-10 Ivana Osmanovic The Prayer……………………………………………………………………………………………10-11 Taylor Gall 1973-Now……….…………………………………………………………………………..…......…….11 What Happened When You Left Me………………………………………………..……………...11-12 Weighted Wings………………………………………………………..………………………………..12 Mary Klauer Nostalgia’s Bliss…………………………………………………………………………………………13 Shannon Cassells On The Rocks…………………………………………………………………………………….….14-17 Brian Torbik Good Girls….……………………….………………………………………...………………..........17-18 Jared Golub Birthday Stroganoff.……………….… ………………………………...…...……………………...18-20 Sunny Days of Solitude………..…………….……………………………...……………….......…20-23 Meredith Augspurger Rotten…………………………………………………………………………….………..………….….23 Color Blind………………………………………………………………………….........................23-24 -

Q: Today Is the 30Th of January 2006

The Association for Diplomatic Studies and Training Foreign Affairs Oral History Project AMBASSADOR MARC GROSSMAN Interviewed by: Charles Stuart Kennedy Initial interview date: January 30, 2006 Copyright 2016 ADST Q: Today is the 30th of January 2006. This is an interview with Marc Grossman done on behalf of the Association for Diplomatic Studies and Training and I’m Charles Stuart Kennedy. You go by Marc? GROSSMAN: I do. Q: What happens, why are some Marcs spelled with a C and some with a K? Do you have any idea? GROSSMAN: My dad always said it was his contribution to culture. Q: Okay. Well, we’ll start talking about him but first, when and where were you born? GROSSMAN: I was born in September of 1951 in Los Angeles, California. Q: Where in Los Angeles? GROSSMAN: In East Los Angeles. My parents lived in Pico Rivera, or then, just Pico. Q: Okay. Let’s talk about your, sort of your background. On your family’s side, let’s talk about the father’s family, the Grossmans. Do you have any idea where they came from? GROSSMAN: We have a vague idea. Both of my father’s parents, my grandmother and grandfather, were immigrants to the United States. They came separately from Chernowitz, which is now Ukraine but my father believes at the time of their immigration it was Romania. I think they came to the United States in the 1920s. They moved to New York, met in the US and settled in the Bronx. They then moved, first to Arizona and then to California in the 1940s, where my grandfather used to sew. -

World War I Veterans in Pre-Code Film

The Pennsylvania State University The Graduate School School of Humanities SPENT BULLETS: WORLD WAR I VETERANS IN PRE-CODE FILM A Dissertation in American Studies by Tiffany I. Weaver ©2018 Tiffany I. Weaver Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy December 2018 The dissertation of Tiffany I. Weaver was reviewed and approved* by the following: Charles Kupfer Associate Professor of American Studies and History Dissertation Advisor Chair of Committee Simon J. Bronner Distinguished Professor of American Studies and Folklore Anthony Buccitelli Associate Professor of American Studies and Communications Robin Redmon Wright Associate Professor of Lifelong Learning and Adult Education John Haddad Professor of American Studies and Popular Culture Chair of the Graduate Program in American Studies *Signatures are on file in the Graduate School ii ABSTRACT Films depicting World War I and its aftermath began production almost as soon as the war began, although it would be roughly a decade before these films became more prevalent and popular. Many of these films were important in helping the public navigate the aftermath of the conflict and reflected the changing society of the 1920s and early 1930s. Studying these films can help provide a better understanding of the culture in the United States that emerged during the Interwar period and how society reacted to these changes. Of particular importance are the films depicting the experience of the solider upon returning home. Following World War I, veterans across the United States and Europe experienced issues with readjustment to civilian life, struggled with shell shock, and faced unemployment. -

Collection "Ma Collection" De Samafar

Collection "ma collection" de samafar Artiste Titre Format Ref Pays de pressage 113 Tonton Du Bled Maxi 33T 37000784002 2 France 16 Bit Where Are You ? Maxi 45T 888 417-1 France 16 Bit Changing Minds Maxi 45T 888 814-1 France 2 Unlimited Tribal Dance Maxi 45T 190377 1 France 2 Unlimited The Real Thing Maxi 33T 190 667.1 France 2 Unlimited No One Maxi 33T 190 725.1 France 2 Unlimited No Limit Maxi 45T 190 319.1 France 2 Unlimited Maximum Overdrive Maxi 45T 190 539.1 France 2 Unlimited Faces Maxi 33T BYTE 12024 - 181.295.5Belgique 20 Years After Magical Medley Maxi 45T 560.136 France 49 Ers Die Walkure Maxi 45T 8.917 France 49 Ers Die Walkure Maxi 45T 8.917 France 501's Feat. Desiree Let The Night Take The Blame Maxi 45T 792849 France 99.9 % Check Out Th Groove Maxi 45T DEBTX 3054 Royaume-Uni A Caus Des Garcons A Caus Des Garcons Maxi 45T 248075-0 Allemagne A Taste Of Honey Boogie Oogie Oogie Maxi 45T 2S 052 52814 Z France A-ha Touchy ! Maxi 45T 921 044-0 D Allemagne A-ha The Sun Always Shine On T.v. Maxi 45T 920 410-0 D Allemagne A-ha Take On Me Maxi 45T 920 336-0 D Allemagne A-ha Stay On These Roads LP 925733-1 / WX 166 Allemagne A-ha Stay On These Roads LP 925733-1 Espagne A-ha I've Been Losing You Maxi 45T 920 557-0 D Allemagne A-ha Cry Wolf Maxi 45T 920 610-0 D Allemagne A.ha The Living Daylights Maxi 45T 920 736-0 D Allemagne Aaliyah Try Again (promo Club) Maxi 33T VUSTDJ167 EU Abba Vouley-vous (vinyl Rouge) Maxi 33T 310801 France Abba Vouley-vous (vinyl Bleu) Maxi 33T 310801 France Abba The Day Before You Came Maxi 33T 310954 France -

Famous First Words @ Writers' Camp

Digital Proofer Famous First Words @ Writers' Camp Famous First Words Authored by Wake Forest Univer... 5.0" x 8.0" (12.70 x 20.32 cm) Black & White on Cream paper 258 pages ISBN-13: 9781618460578 ISBN-10: 1618460579 Please carefully review your Digital Proof download for formatting, grammar, and design issues that may need to be corrected. We recommend that you review your book three times, with each time focusing on a different aspect. Check the format, including headers, footers, page 1 numbers, spacing, table of contents, and index. 2 Review any images or graphics and captions if applicable. 3 Read the book for grammatical errors and typos. Once you are satisfied with your review, you can approve your proof and move forward to the next step in the publishing process. To print this proof we recommend that you scale the PDF to fit the size of your printer paper. 1 Famous First Words @ Writers' Camp By Wake Forest University Writers’ Camp 2018 2 3 To the marginalized and the silenced To all those who encouraged us to write!” ISBN 978-1-61846-057-8 Copyright © 2018 by the Authors Cover photography courtesy of Susan S. Smith All rights reserved, including the right of reproduction, in whole or in part, in any form. Produced and Distributed By: Library Partners Press ZSR Library Wake Forest University 1834 Wake Forest Road Winston-Salem, North Carolina 27106 www.librarypartnerspress.org Manufactured in the United States of America 4 5 ABOUT THE BOOK The inspiration for Writers' Camp @ ZSR came after a group of ZSR librarians heard Jane McGonigal present “Find the Future: The Game” during the American Library Association’s 2014 Annual Conference. -

Transatlantic Partnership: Interviews with His Excellency Andrew H

Spring 2016 Re:Views Transatlantic Partnership: Interviews with His Excellency Andrew H. Schapiro and Michael Žantovský The Many Sides of Jeffrey Alan Vanderziel US Elections 2016 Tento projekt vznikl za finanční podpory a taktéž nemateriální pomoci Grantu TGM Spolku absolventů a přátel Dear readers… As always, I would like to thank you all for your support Masarykovy univerzity, Filozofické fakulty MU, Katedry anglistiky a amerikanistiky FF MU, Brno Expat Centre, and I hope you shall enjoy reading Issue IV as much as ESCape, Krmítka a Plánotisku. The king is dead. we enjoyed working on it! Long live the queen! This project was realized with financial as well as non-material help and support of TGM Grants of Alumni and On behalf of the Re:Views Magazine, Friends of Masaryk University, Faculty of Arts MU, Department of English and American Studies FA MU, Brno Well, although our king did not quite die – as I am relieved Markéta Šonková Expat Centre, ESCape, Krmítko, and Plánotisk. to say – it is still an end of one era. Finally, after all those editor-in-chief years of reading about it, I can begin to imagine how the British felt when Edward VII sat on the throne after Queen Victoria. Just like them, not many of us remember anyone else but Jeff to sit on the throne of the Department Contents of English and American Studies. So to console our hearts and minds, let us all celebrate the fact that he still stays The Many Sides of Jeffrey Alan as our viceroy. Vanderziel ................................ 4 - 9 Back to 21st century and the simile-free language. -

01-2016 Index Good Short Total Song 1 50 0 50 COLDPLAY

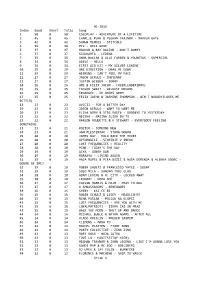

01-2016 Index Good Short Total Song 1 50 0 50 COLDPLAY - ADVENTURE OF A LIFETIME 2 45 0 45 CHARLIE PUTH & MEGHAN TRAINOR - MARVIN GAYE 3 42 0 42 SHAWN MENDES - STITCHES 4 39 0 39 MI2 - BELI GRAD 5 37 0 37 MADCON & RAY DALTON - DON'T WORRY 6 37 0 37 SIDDHARTA - LEDENA 7 35 0 35 ANNA NAKLAB & ALLE FARBEN & YOUNOTUS - SUPERGIRL 8 34 0 34 ADELE - HELLO 9 34 0 34 FIRST AID KIT - MY SILVER LINING 10 29 0 29 ONE DIRECTION - DRAG ME DOWN 11 29 0 29 WEEKEND - CAN'T FEEL MY FACE 12 27 0 27 JASON DERULO - CHEYENNE 13 27 0 27 JUSTIN BIEBER - SORRY 14 26 0 26 OMI & FELIX JAEHN - CHEERLEADER(RMX) 15 25 0 25 TAYLOR SWIFT - WILDEST DREAMS 16 25 0 25 ČEDAHUČI - ČE HOČEŠ GREM 17 25 0 25 FELIX JAEHN & JASMINE THOMPSON - AIN'T NOBODY(LOVES ME BETTER) 18 23 0 23 AVICII - FOR A BETTER DAY 19 23 0 23 JASON DERULO - WANT TO WANT ME 20 23 0 23 ELINA BORN & STIG RASTA - GOODBYE TO YESTERDAY 21 22 0 22 NEISHA - NAJINA SLIKA IN TI 22 22 0 22 MARLON ROUDETTE & K STEWART - EVERYBODY FEELING SOMETHING 23 21 0 21 HOZIER - SOMEONE NEW 24 21 0 21 JAN PLESTENJAK - STARA DOBRA 25 20 0 20 JAMES BAY - HOLD BACK THE RIVER 26 20 0 20 AVTOMOBILI - STOPINJE V SNEGU 27 20 0 20 LOST FREQUENCIES - REALITY 28 20 0 20 PINK - TODAY'S THE DAY 29 19 0 19 ALYA - DOBER DAN 30 19 0 19 MARAAYA - LIVING AGAIN 31 19 0 19 ANJA RUPEL & PIKA BOŽIČ & NUŠA DERENDA & ALENKA GODEC - DOBRO SE IMEJ 32 19 0 19 ROBIN SHULTZ & FRANCESCO YATES - SUGAR 33 19 0 19 SOLO MILA - SANJAM TVOJ GLAS 34 18 0 18 ADAM LEVINE & R. -

Justin Williams My Country’S Kitchen 17-21 Drawing by Richie Gould

“For a Better World” 2018 Poems and Drawings on Peace and Justice by Greater Cincinnati Artists Editor: Saad Ghosn “Being at the service of dialogue and peace also means being truly determined to minimize and, in the long term, to end the many armed conflicts throughout our world. Here we have to ask ourselves: Why are deadly weapons being sold to those who plan to inflict untold suffering on individuals and society? Sadly, the answer, as we all know, is simply for money: money that is drenched in blood, often innocent blood. In the face of this shameful and culpable silence, it is our duty to confront the problem and to stop the arms trade.” Pope Francis “Where justice is denied, where poverty is enforced, where ignorance prevails, and where any one class is made to feel that society is an organized conspiracy to oppress, rob and degrade them, neither persons nor property will be safe.” Frederick Douglass Published in 2018 by Ghosn Publishing ISBN 978-1-7321135-0-3 Foreword “Poetry is born in the caverns of the human heart, pausing before that which yearns. Poetry can contribute to social justice when it moves others’ hearts, wakes people up to the world around them, stirs the moral imagination, or kindles the embers of hope.” writes Jean Stokan, poet and Director of the Justice Team of the Sisters of Mercy of the Americas in Washington, DC. In this 15th edition of “For a Better World” seventy three poets and thirty seven visual artists, use their voice and their artistic power to contribute to social justice, to combat darkness, violence and evil, and to spread instead love, peace and justice that they would like to see prevail.