HALF a DREAM a Thesis Submitted to Kent State University in Partial

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Record Store Day 2020 (GSA) - 18.04.2020 | (Stand: 05.03.2020)

Record Store Day 2020 (GSA) - 18.04.2020 | (Stand: 05.03.2020) Vertrieb Interpret Titel Info Format Inhalt Label Genre Artikelnummer UPC/EAN AT+CH (ja/nein/über wen?) Exclusive Record Store Day version pressed on 7" picture disc! Top song on Billboard's 375Media Ace Of Base The Sign 7" 1 !K7 Pop SI 174427 730003726071 D 1994 Year End Chart. [ENG]Pink heavyweight 180 gram audiophile double vinyl LP. Not previously released on vinyl. 'Nam Myo Ho Ren Ge Kyo' was first released on CD only in 2007 by Ace Fu SPACE AGE 375MEDIA ACID MOTHERS TEMPLE NAM MYO HO REN GE KYO (RSD PINK VINYL) LP 2 PSYDEL 139791 5023693106519 AT: 375 / CH: Irascible Records and now re-mastered by John Rivers at Woodbine Street Studio especially for RECORDINGS vinyl Out of print on vinyl since 1984, FIRST official vinyl reissue since 1984 -Chet Baker (1929 - 1988) was an American jazz trumpeter, actor and vocalist that needs little introduction. This reissue was remastered by Peter Brussee (Herman Brood) and is featuring the original album cover shot by Hans Harzheim (Pharoah Sanders, Coltrane & TIDAL WAVES 375MEDIA BAKER, CHET MR. B LP 1 JAZZ 139267 0752505992549 AT: 375 / CH: Irascible Sun Ra). Also included are the original liner notes from jazz writer Wim Van Eyle and MUSIC two bonus tracks that were not on the original vinyl release. This reissue comes as a deluxe 180g vinyl edition with obi strip_released exclusively for Record Store Day (UK & Europe) 2020. * Record Store Day 2020 Exclusive Release.* Features new artwork* LP pressed on pink vinyl & housed in a gatefold jacket Limited to 500 copies//Last Tango in Paris" is a 1972 film directed by Bernardo Bertolucci, saxplayer Gato Barbieri' did realize the soundtrack. -

The Flintstones (1960-1966), About a “Modern Stone-Age Family,” Was The

Columbia Pictures) to develop a prime-time animated series. They worked out the concept of parodying current situation comedies, especially The Honeymooners and Father Knows Best, with the twist of setting them in a different historical era. Cartoonists Dan Gordon and Bill Benedict had the idea to use a Stone Age setting (although the Fleischer Studios pro- duced a similar series of Stone Age Cartoons back in 1940). The concept was bought by ABC, and premiered Sept. 30, 1960. Voiced by Alan Reed, Jr. (Fred Flintstone), Mel Blanc (Barney Rubble), Jean VanderPyl (Wilma Flintstone) and veteran actress Bea Benaderet (Betty Rubble), The Flintstones finished the season in the Nielsen ratings’ top 20, and won a number of industry awards, including the Golden Globe, and an [email protected] Emmy nomination for best comedy series of 1960-61. A clear appeal of the series lays in its parody of sitcom for- mula plots, and there are elements of satire in the way modern consumer conveniences are turned into sight gags. One of the show’s favorite gags was to have cameos by Stone Age versions of modern celebrities (Ann Margrock, Stony Curtis, etc.). The most popular gimmick was Wilma’s pregnancy, ending with the February 1963 “birth” of their little girl, Pebbles. The next season the Rubbles adopted Bamm-Bamm, a little boy of incredible strength and a one- word vocabulary. By the fifth and sixth seasons, the show began to use more storylines aimed at kids, with new neighbors the Grue- somes (a spin on The Munsters and The Addams Family), and magical space alien The Great Gazoo (Harvey Korman). -

Why Am I Doing This?

LISTEN TO ME, BABY BOB DYLAN 2008 by Olof Björner A SUMMARY OF RECORDING & CONCERT ACTIVITIES, NEW RELEASES, RECORDINGS & BOOKS. © 2011 by Olof Björner All Rights Reserved. This text may be reproduced, re-transmitted, redistributed and otherwise propagated at will, provided that this notice remains intact and in place. Listen To Me, Baby — Bob Dylan 2008 page 2 of 133 1 INTRODUCTION .................................................................................................................................................................. 4 2 2008 AT A GLANCE ............................................................................................................................................................. 4 3 THE 2008 CALENDAR ......................................................................................................................................................... 5 4 NEW RELEASES AND RECORDINGS ............................................................................................................................. 7 4.1 BOB DYLAN TRANSMISSIONS ............................................................................................................................................... 7 4.2 BOB DYLAN RE-TRANSMISSIONS ......................................................................................................................................... 7 4.3 BOB DYLAN LIVE TRANSMISSIONS ..................................................................................................................................... -

United States Patent and Trademark Office

UNITED STATES PATENT AND TRADEMARK OFFICE TRADEMARK PUBLIC ADVISORY COMMITTEE MEETING Alexandria, Virginia Friday, February 11, 2011 2 1 PARTICIPANTS: 2 TPAC Members: 3 JOHN B. FARMER, Chair 4 JAMES G. CONLEY 5 MARY BONEY DENISON 6 TIMOTHY J. LOCKHART 7 KATHRYN B. PARK 8 DEBORAH HAMPTON 9 MAURY TEPPER 10 ANNE CHASSER 11 Union Members: 12 HOWARD FRIEDMAN 13 RANDALL P. MYERS 14 HAROLD E. ROSS 15 Also Present: 16 DEBORAH COHN, Commissioner 17 DANA ROBERT COLARULLI Director, Office of Government Affairs 18 ANTHONY P. SCARDINO ………………………………………..Chief Financial Officer 20 JOHN OWENS Chief Information Officer 21 GERARD ROGERS TTAB Chief Judge 22 3 1 PARTICIPANTS (CONT'D): 2 WILLIAM COVEY Office of Enrollment and Discipline 3 ………..CYNTHIA LYNCH Administrator for Examination Policy 4 HARRY I. MOATZ Office of Enrollment and Discipline 5 ERIK M. PELTON Erik M. Pelton and Associates 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 * * * * * 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 4 1 P R O C E E D I N G S 2 (9:00 a.m.) 3 CHAIRMAN FARMER: If everyone can take 4 their seats, please. I'd like to welcome 5 everybody to the TPAC meeting. My name is John 6 Farmer and I chair the committee. 7 I know this is old hat to perhaps 8 everybody in the room because I look around the 9 room and see so many familiar faces, but just in 10 case someone is new -- or for folks watching at 11 home -- this meeting is being webcast and it's 12 also being transcribed. -

Monument Creek Watershed Landscape Assessment

MonumentMonument CreekCreek WatershedWatershed LandscapeLandscape AssessmentAssessment a Legacy Resource Management Program Project Monument Creek Watershed Landscape Assessment prepared for: United States Air Force Academy 8120 Edgerton Dr Ste 40 Air Force Academy CO 80840-2400 prepared by: John Armstrong and Joe Stevens Colorado Natural Heritage Program 254 General Services Building Colorado State University, College of Natural Resources Fort Collins CO 80523 31 January 2002 Copyright 2002 Colorado Natural Heritage Program Cover photo: Panorama of Pikes Peak and the Rampart Range (the western boundary of the Monument Creek Watershed) from Palmer Park. Photograph by J. Armstrong. Funding provided by the Legacy Resource Management Program, administered by the US Army Corps of Engineers. table of contents list of figures ................................................................................................3 list of tables ..................................................................................................3 list of maps ..................................................................................................3 list of photographs .....................................................................................4 acknowledgements...........................................................................................5 introduction .......................................................................................................7 project history .............................................................................................7 -

Manchester Historical Society

U - MANCHESTER HERALD. Friday. May 9.1986 WEEKFND PLUS SPORTS m i Rhoda is loving Coventry tightens TAG SALE her new TV role conference race Are things piling up? Then why not have a TAG SALE? The best way to announce it is with a Herald Tag Sale ... magazine Inside > .. page 11 Classified Ad. When you place your ad, you’ll receive ONE TAG SALE SIGN FREE, compliments of The Herald. STOP IN AT OUR OFFICE, 1 HERALD SQUARE. MANCHESTER CAMPERS/ I MISCELLANEOUS H jJ C A R S Q j J O U B CARS aurliPBlrr HrralJi FOR SALE TRAILERS AUTOMOTIVE TAG SALES TAG SALES H TAG SALES FOR SALE FmiSMf ED N ) Manchester -- A City ol Village Charm Two E7B X 14 Whitewall M<A>chester High School 1970 Ford Torino. 302 en Apache Yuma Pop up tires with rims, used I'/i Tag Sale-Center Congre Moving sale. Multi- 1981 Black 280 ZK Turbo 1971 Ford Van, 302, stand camper. Stove, refrldger- Too Sole. Mov 17« 9am- gatlonal Church Man family: 2 humidifiers, 2 gine In excellent condi T-Bar, AT, leather uphals- ard transmission, custom years. Good condition $35 3pm. Spaces available. tion, only 78,000 original tery, wire wheels, Nordl otor, sink. Sleeps 5 plus. each. 643-6463 after 25 Cents Call 647-9504 or 643-0219. chester, Sat. May 10,9am. dehumidiflers, excercise ized with bed, very little Cleon SiSharp. $1,000firm. Saturday, May 10,1986 A "You won't believe It equipment, T.V., typewri miles. Transmission and wheel. In mint condition, rust, $1700 or Best offer 4:00pm. -

Mitch Maclay Sings Just for You

MITCH MACLAY SINGS JUST FOR YOU A Play in One Act by Craig Bailey Craig Bailey 350 Woodbine Rd Shelburne VT 05482-6777 (802) 655-1197 ©2019 Craig Bailey [email protected] All rights reserved www.mitchmaclay.com CHARACTERS CHRISTOPHER WOOD Early-30s. Program Director and morning board operator for radio station TRU-92. HE capitalizes on the invisibility of his medium by dressing in casual clothing including baggy khakis, sneakers with no socks, and a comfortable T-shirt sporting the logo of an alternative band. His cynical attitude and occasionally snide veneer reflect the mind-set of an up-and- coming industry man who somehow made a wrong turn only to find himself, inexplicably, in rural Iowa. LORALIE KENT Early- to mid-20s. Evening board operator for TRU-92. SHE is dressed in simple slacks, blouse and stocking feet at rise -- with a fresh, natural, cheerful face that's wasted on the radio. Her eccentricity and inclination for seemingly pointless chatter disguise her high level of intelligence -- an asset that's thwarted only by her rose-colored naivete. SETTING Front office of radio station TRU-92 in a small Iowa town TIME A Saturday in the late-1980s 1. ACT I Scene 1 (The second story front office of radio station TRU-92 in a small Iowa town, late-1980s. The furnishings and decor are about 30 years behind the times. The overall atmosphere is drab, bordering on depressed. A doorway UC leads to a hallway. Entranceways DR and DL lead to the air studio and sales offices, respectively. -

Bill Harry. "The Paul Mccartney Encyclopedia"The Beatles 1963-1970

Bill Harry. "The Paul McCartney Encyclopedia"The Beatles 1963-1970 BILL HARRY. THE PAUL MCCARTNEY ENCYCLOPEDIA Tadpoles A single by the Bonzo Dog Doo-Dah Band, produced by Paul and issued in Britain on Friday 1 August 1969 on Liberty LBS 83257, with 'I'm The Urban Spaceman' on the flip. Take It Away (promotional film) The filming of the promotional video for 'Take It Away' took place at EMI's Elstree Studios in Boreham Wood and was directed by John MacKenzie. Six hundred members of the Wings Fun Club were invited along as a live audience to the filming, which took place on Wednesday 23 June 1982. The band comprised Paul on bass, Eric Stewart on lead, George Martin on electric piano, Ringo and Steve Gadd on drums, Linda on tambourine and the horn section from the Q Tips. In between the various takes of 'Take It Away' Paul and his band played several numbers to entertain the audience, including 'Lucille', 'Bo Diddley', 'Peggy Sue', 'Send Me Some Lovin", 'Twenty Flight Rock', 'Cut Across Shorty', 'Reeling And Rocking', 'Searching' and 'Hallelujah I Love Her So'. The promotional film made its debut on Top Of The Pops on Thursday 15 July 1982. Take It Away (single) A single by Paul which was issued in Britain on Parlophone 6056 on Monday 21 June 1982 where it reached No. 14 in the charts and in America on Columbia 18-02018 on Saturday 3 July 1982 where it reached No. 10 in the charts. 'I'll Give You A Ring' was on the flip. -

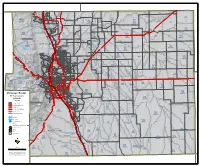

Drainage Basins D R R a F A

EEllbbeerrtt CCoouunnttyy Coommeerrccee Rdd d d R R h h Douglas County a Douglas County a m m rr a a d d D R D R R R t t Fremont C k Fremont P C k r P r w e w W rr e e h a W e a av h E h avy e h y e E s O d d s st rs Oa DD d r k r o d t r a n e r o n relllla ee k Dr a K r n Fort e L K n Fort L B kk e Carpenter n C B Carpenter R n C b R Bald u L b ee u Bald L r S v Plum r v ee Plum l k h i o e k h r i o e l r RAMAH D g rr l l D g l n a l n a d T G G T i h r G d G ok St h r CC o E ro St r B ok i Bro o r t i E t n d d Sundance Mountain d d e n r E p e r E Creek kk p R oo W g E Creek H R g E W ll v Mountain w v H w R u R R M ountain R u r Creek r Creek W EE t W r cc o H i r h t o H i e e a Antelope h n D a d n e i D e p n a d Antelope o n p o e g n a n r r g WW dd e e d g o e e d g T o H R n PLPL0400 e e T l n 8285 l e T H R T g PLPL0400 D g F m PLPL020 0 F West D u e D u m PLPL0200 PLP0600 D e v a West r a r d v t PLP0600 d t m l r a i l r h k S l k l i h rr a m S i l r l i dd g c n d r R w c r amah n E R Rd g i r a E Ramah w o T DD u i a PALMER LAKE o D T amah Rd D E R u G R d k ah R r G d RR am h * R k e E A r n d R o e n A * h oo S S o a n c e a d e n r c d cc r Creek C m r r W ee D C W m D aa s o e Creek R C l s r Ca o e o l t S a h r R t e rr b h r r d e d o b S e p dr D d e p ra D e R M l a l oss a e L R M Rock l D a l oss Rd mm L Dr e Rock Rd u DD r r l s e m a r l s lm t a u l B s r o B aa l t t s r o l t h M lh r P l r M F C S P e e e l e C S g gg a e F l e g a i l n a W Ramah Rd i l n a Rd t o A W Ramah o p t A d r C nn p d r C -

The BG News January 19, 1995

Bowling Green State University ScholarWorks@BGSU BG News (Student Newspaper) University Publications 1-19-1995 The BG News January 19, 1995 Bowling Green State University Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.bgsu.edu/bg-news Recommended Citation Bowling Green State University, "The BG News January 19, 1995" (1995). BG News (Student Newspaper). 5792. https://scholarworks.bgsu.edu/bg-news/5792 This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works 4.0 License. This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the University Publications at ScholarWorks@BGSU. It has been accepted for inclusion in BG News (Student Newspaper) by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@BGSU. {Efc3S6 f3ttog The BG News 'Celebrating 75 Years of Excellence' Thursday, January 19,1995 Bowling Green, Ohio Volume 82, Issue 81 University updates computers Student-organized push key factor in success of proposal Jim Barker chasing Gateway Pentium pro- The BG News cessors, which are more func- tional than the computers that Computer Services purchased had been in the labs, Conrad said. 200 new computers during win- "What you get with the Power ter break for University labs, and PCs and the Pentium processors 106 more are slated to arrive in is more memory, more hard the near future. The additions drive capability and a more func- are partly the result of a student- tional machine," Conrad said. organized push for updated University Student Govern- equipment. ment cabinet member Randy The push for new equipment in Stewart became involved in the the labs started last fall, when effort after reading flyers posted students began voicing com- outside the computer labs. -

Cogjm.Rmo-604.Pdf (1.625Mb)

RMO- 6~~lV 3m!c -o UNITED STATES DEPART~illNT OF THE INTERIOR GEOLOGICAL SURVEY INVESTIGATIONS OF DO~STIC RADIOACTIVE RAW MATERIALS, BERYLLIUM, AND OTHER TRACE ELE~NTS (J PREPARED FOR U. S. ATOMIC ENERGY COMMISSION MONTHLY REPORT--NOVEMBER 1951 TRACE ELEMENTS OFFICE C] Neither the United States Government nor any agency thereof, nor any.oftheir employees, makes any warranty, express or implied, or assumes any legal liability or responsibility for the accuracy, completeness, or usefulness of any information, apparatus, product, or process disclosed in this report, or represents that its use would not infringe privately owned rights. Reference therein to any specific commercial product, process, or service by trade name, trademark, manufacturer, or otherwise, does not necessarily constitute or imply its endorsement, recommendation, or favoring by the United States Government or any agency thereof. The views and opinions of authors expressed herein do not necessarily state or reflect those of the United States Government or any agency thereof. REPRODUCED FROM BEST AVAILABLE COPY -2- CJ .3 Page SUIDinary .......................................................................... o .......... o o .................. " ~ .......... .. 7 Reconnaissance investigations, domestic .......................................................... .. 9 Property examinations .................................................................................. .. 9 Copper-uranium deposits in sandstones .................................................... .. 9 Relation -

Marti's Movies Make Music Keith Drums up a New Interviewee Mr

October 2019 October 111 In association with "AMERICAN MUSIC MAGAZINE" ALL ARTICLES/IMAGES ARE COPYRIGHT OF THEIR RESPECTIVE AUTHORS. FOR REPRODUCTION, PLEASE CONTACT ALAN LLOYD VIA TFTW.ORG.UK At the recent soiree at Gerry’s, Shaunny Longlegs tries out his novel microphone stand © Nigel Bewley while Rockin’ Gerry sticks with the tried and trusted manual method. (Keith Woods available for mic stand © Nigel Bewley hire at reasonable rates) Marti’s movies make music Keith drums up a new interviewee Mr Angry reviews a radio comedy show We “borrow” yet more stuff from Nick Cobban Jazz Junction, Soul Kitchen, Blues Rambling And more.... 1 The September issue (#151) of American Music Magazine has plenty for Woodies to enjoy. First and foremost is Keith Woods’ interview with rockabilly favourite and bass-player Billy Harlan. There is an introduction by Woody Dominique Anglares and the interview is accompanied by vintage photos as well as a session discography. Another main feature is on Little Richard’s role model Billy Wright, the Atlanta blues and R&B singer – this accompanied by lots of photos, clippings from Billboard and Cashbox, label shots in colour, and definitive session and record discographies. The magazine also includes an in-depth article on Nashville songwriter and performer Royce Porter, whilst the instrumentals series continues for lovers of the genre, and then add to this an essay by Kaye Garren, one of the members of The Heathens whose acetate recorded at the Sun studio in 1956 has recently been issued on 45rpm. As well as the label shots, the colour section includes photos of Waylon Jennings, Jessie Colter and Willie Nelson when they visited Sweden in 1970.