Blue Ribbon Committee on Slum Housing and Inviting Others to Join the Panel

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Table of Contents

Table of Contents 1. Defense Travel System (DTS) – #4373 2. DOD Travel Payments Improper Payment Measure – #4372 3. Follow up Amendment 4. DOD Earmarks Cost and Grading Amendment – #4370 5. Limitation on DoD Contract Performance Bonuses – #4371 1. Amendment # 4373 – No Federal funds for the future development and operation of the Defense Travel System Background The Defense Travel System (DTS) is an end-to-end electronic travel system intended to integrate all travel functions, from authorization through ticket purchase to accounting for the Department of Defense. The system was initiated in 1998 and it was supposed to be fully deployed by 2002. DTS is currently in the final phase of a six-year contract that expires September 30, 2006. In its entire history, the system has never met a deadline, never stayed within cost estimates, and never performed adequately. To date, DTS has cost the taxpayers $474 million – more than $200 million more than it was originally projected to cost. It is still not fully deployed. It is grossly underutilized. And tests have repeatedly shown that it does not consistently find the lowest applicable airfare – so even where it is deployed and used, it does not really achieve the savings proposed. This amendment prohibits continued funding of DTS and instead requires DOD to shift to a fixed price per transaction e-travel system used by government agencies in the civilian sector, as set up under General Services Administration (GSA) contracts. Quotes of Senators from last year’s debate • Senator Allen stated during the debate last year that “as a practical matter we would like to have another year or so to see (DTS) fully implemented.” • Senator Coleman stated during the debate, “… if we cannot get the right answers we should pull the plug, but now is not the time to pull the plug. -

12Th Grade Curriculum

THE TOM BRADLEY PROJECT STANDARDS: 12.6.6 Evaluate the rolls of polls, campaign advertising, and controversies over campaign funding. 12.6.6 Analyze trends in voter turnout. COMMON CORE STATE KEY TERMS AND ESSAY QUESTION STANDARDS CONTENT Reading Standards for Literacy in elections History/Social Studies 6-12 How did the election of Tom shared power Bradley in 1973 reflect the local responsibilities and Writing Standard for Literacy in building of racial coalitions in authority History/Social Studies 6-12 voting patterns in the 1970s and Text Types and Purpose the advancement of minority 2. Write informative/explanatory texts, opportunities? including the narration of historical events, scientific procedures/experiments, or technical processes. B. Develop the topic with relevant, well-chosen facts, definitions, concrete details, quotations, or other information and expamples LESSON OVERVIEW MATERIALS Doc. A LA Times on Voter turnout, May 15, 2003 Day 1 View Module 2 of Tom Bradley video. Doc. B Voter turnout spreadsheet May 15, 2003 (edited) Read Tom Bradley biography. Doc. C Statistics May 15,2003 Day 2 Doc. D Tom Bradley biography Analyze issues related to voter turnout in Doc. E Census, 2000 2013 Los Angeles Mayoral Election and Doc, F1973 Mayoral election connections to the 1973 campaign for Doc .G Interview 1973 Mayor. Doc. H Election Night speech 1989 Day 3 Doc I LA Times Bradley’s first year 1974 Analyze issues in 1973 campaign. Doc. J LA Times Campaign issues 1973 Analyze building of racial coalitions Doc K LA Times articles 1973 among voters. Day 4 Doc. L LA Times campaign issues 1973 Write essay. -

MOST BUSINESS-FRIENDLY in This Issue: City National Bank and Toyota Receive 2006 Eddy Awards • 2006 Eddy Awards Coverage & Photos

EL SEGUNDO: MOST BUSINESS-FRIENDLY In This Issue: City National Bank and Toyota receive 2006 Eddy Awards • 2006 Eddy Awards Coverage & Photos • Change in LAEDC Governance • Business Assistance Mid-Year Report • International Update • Transportation Update For full coverage and photo highlights, turn to page 6 C-17 PRODUCTION LINE CONTINUES Region’s Red Team enlisted support from Governor, US President Take a Look Into On September 29, President this national asset and proven Congress and President Bush to George W. Bush signed a workhorse for military and save the thousands of jobs at the THE FUTURE Defense Appropriations Bill, humanitarian missions. manufacturing plant in Long of Our Economy allowing $4.4 billion in funding Beach by continuing to fund the for the C-17 program. The bill The Red Team hopes to capital- C-17 program. saves 5,500 direct jobs at the ize on the effort's momentum to Boeing plant in Long Beach extend the life of the C-17 pro- Addressing the Boeing employ- 2007-2008 through the end of 2009. duction line even further. With ees, the Governor said, “We have 64 more planes, the production all been fighting for this for years. ECONOMIC The fight to save the C-17 pro- line could be extended until We have been working overtime duction line has indeed been a 2011. to keep all of you working...I FORECAST tough road since 2005, making joined with other governors to the signing of the bill a real victo- In March, the Australian govern- push for continued production of ry for the C-17 Program Red ment placed an order for four C- the incredible aircraft. -

Governing Urban School Districts: Efforts in Los Angeles to Effect

THE ARTS This PDF document was made available from www.rand.org as a public CHILD POLICY service of the RAND Corporation. CIVIL JUSTICE EDUCATION Jump down to document ENERGY AND ENVIRONMENT 6 HEALTH AND HEALTH CARE INTERNATIONAL AFFAIRS The RAND Corporation is a nonprofit research NATIONAL SECURITY POPULATION AND AGING organization providing objective analysis and effective PUBLIC SAFETY solutions that address the challenges facing the public SCIENCE AND TECHNOLOGY and private sectors around the world. SUBSTANCE ABUSE TERRORISM AND HOMELAND SECURITY TRANSPORTATION AND INFRASTRUCTURE Support RAND WORKFORCE AND WORKPLACE Browse Books & Publications Make a charitable contribution For More Information Visit RAND at www.rand.org Explore RAND Education View document details Limited Electronic Distribution Rights This document and trademark(s) contained herein are protected by law as indicated in a notice appearing later in this work. This electronic representation of RAND intellectual property is provided for non- commercial use only. Permission is required from RAND to reproduce, or reuse in another form, any of our research documents for commercial use. This product is part of the RAND Corporation technical report series. Reports may include research findings on a specific topic that is limited in scope; present discus- sions of the methodology employed in research; provide literature reviews, survey instruments, modeling exercises, guidelines for practitioners and research profes- sionals, and supporting documentation; or deliver preliminary findings. All RAND reports undergo rigorous peer review to ensure that they meet high standards for re- search quality and objectivity. Governing Urban School Districts Efforts in Los Angeles to Effect Change Catherine H. Augustine, Diana Epstein, Mirka Vuollo The research described in this report was conducted within RAND Education for the Presidents' Joint Commission on LAUSD Governance. -

PDF of This Issue

MIT's The Weather Oldest and Largest Today: Light snow or rain, 38°F (30C) Tonight: Clear, cold, 24°F (-40C) ewspaper Tomorrow: Mostly sunny, 38°F (4°C) Details, Page 2 NUDlber 11 Cambridge, The day, March 11, 199 Corporation Passes 5% Tuition mcrease Student self-help levels remain constant By Z3reena Hussain is the steady decrease in federal ASSOCIATE NEWS EDITOR funding, Williams said. The Executive Committee of the "I continually worry about the MIT Corporation approved a 5 per- cost of education, but I am pleased cent tuition hike for the] 997-98 that we have kept the growth of the academic year, President Vest student budget (tuition, room and announced at Friday's Corporation board) to within about one and a meeting. half percent of the [Consumer Price This amounts to an increase of Index] for the last three years," Vest $1,100 to a tuition level of $23,] 00. said. Including a projected increase in the The Consumer Price Index is a cost of room and board by 3.1 per- standard benchmark used to calcu- cent, the total cost for an MIT edu- late inflation. cation during the coming year will "The cost of education increases be about $29,650. and does so faster than the While the costs of tuition and Consumer Price Index. MIT's edu- room and board increased, the stu- cationa] programs are both labor dent self-help level will remain the and capital intensive, and tuition is same at $8,600. Self-help includes a major source of unrestricted ~he base amount expected of stu- dents to contribute toward financing Tuition, Page II their education before receiving scholarship assistance, and it includes MIT term-time work, loans, and savings. -

Breaking the Bank Primary Campaign Spending for Governor Since 1978

Breaking the Bank Primary Campaign Spending for Governor since 1978 California Fair Political Practices Commission • September 2010 Breaking the Bank a report by the California Fair Political Practices Commission September 2010 California Fair Political Practices Commission 428 J Street, Suite 620 Sacramento, CA 95814 Table of Contents Executive Summary 3 Introduction 5 Cost-per-Vote Chart 8 Primary Election Comparisons 10 1978 Gubernatorial Primary Election 11 1982 Gubernatorial Primary Election 13 1986 Gubernatorial Primary Election 15 1990 Gubernatorial Primary Election 16 1994 Gubernatorial Primary Election 18 1998 Gubernatorial Primary Election 20 2002 Gubernatorial Primary Election 22 2006 Gubernatorial Primary Election 24 2010 Gubernatorial Primary Election 26 Methodology 28 Appendix 29 Executive Summary s candidates prepare for the traditional general election campaign kickoff, it is clear Athat the 2010 campaign will shatter all previous records for political spending. While it is not possible to predict how much money will be spent between now and November 2, it may be useful to compare the levels of spending in this year’s primary campaign with that of previous election cycles. In this report, “Breaking the Bank,” staff of the Fair Political Practices Commission determined the spending of each candidate in every California gubernatorial primary since 1978 and calculated the actual spending per vote cast—in 2010 dollars—as candidates sought their party’s nomination. The conclusion: over time, gubernatorial primary elections have become more costly and fewer people turnout at the polls. But that only scratches the surface of what has happened since 19781. Other highlights of the report include: Since 1998, the rise of the self-funded candidate has dramatically increased the cost of running for governor in California. -

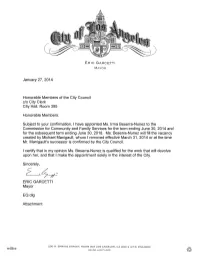

Subject to Your Confirmation, I Have Appointed Ms

ERIC GARCETTI MAYOR January 27, 2014 Honorable Members of the City Council c/o City Clerk City Hall, Room 395 Honorable Members: Subject to your confirmation, I have appointed Ms. Irma Beserra-Nunez to the Commission for Community and Family Services for the term ending June 30, 2014 and for the subsequent term ending June 30, 2018. Ms. Beserra-Nunez will fill the vacancy created by Michael Manigault, whom I removed effective March 31,2014 or at the time Mr. Manigault's successor is confirmed by the City Council. I certify that in my opinion Ms. Beserra-Nunez is qualified for the work that will devolve upon her, and that I make the appointment solely in the interest of the City. Sincerely, L471~ ERIC GARCETTI Mayor EG:dlg Attachment 200 N. SPR!NG STREET, ROOM 303 LOS ANGELES, CA 90012 (213) 978-0600 MAYOR.LACITY.ORG COMMISSION APPOINTMENT FORM Name: Irma Beserra-Nunez Commission: Commission for Community and Family Services End of Term: 6/30/2014 Appointee Information 1. Race/ethnicity: Latina 2. Gender: Female 3. Council district and neighborhood of residence: 5 - SouthValley 4. Are you a registered voter? Yes 5. Prior commission experience: 6. Highest level of education completed: BA California State University Los Angeles 7. Occupation/profession: Advocate for Adult Education 8. Experience(s) that qualifies person for appointment: See attached resume 9. Purpose of this appointment: Replacement 10. Current composition of the commission (excluding appointee): ·,{Narnc{ 1< APCr .. liCD > Gender •.A.r>btdate Te"';~nd~ AI-Mansour, Chancela East LA 14 African American F 25-Seo-12 30-Jun-16 Castillo, Carolina East LA 14 Latina F 30-Jul-10 30-Jun-16 Chan, Yvonne North Valley 12 Asian Pacific Islander F 30-Jul-10 30-Jun-14 Duardo, Debra East LA 14 Latina F 22-Jun-11 30-Jun-14 Garcia, Marv South Valley 2 Latina F 08-0ct-10 30-Jun-16 Hill, PeQQY Central 4 African American F 30-Jul-10 30-Jun-16 lqlehart, Alfreda Central 10 African American F 30-Jul-10 30-Jun-16 Lara, Alicia Central 4 Latina F 28-Seo-10 30-Jun-14 Little, Marc T. -

Sustainable California Ucla Luskin School of Public Affairs Part 2: Water Editor’S Ote

ISSUE #4 / FALL 2016 DESIGNS FOR A NEW CALIFORNIA IN PARTNERSHIP WITH SUSTAINABLE CALIFORNIA UCLA LUSKIN SCHOOL OF PUBLIC AFFAIRS PART 2: WATER EDITOR’S OTE BLUEPRINT A magazine of research, policy, Los Angeles and California THIS ISSUE OF BLUEPRINT IS SEVERAL THINGS AT ONCE: It’s Part 2 of our The theft, fair or not, also established Los Angeles as a city dependent sustainability series, following up on the spring look at power with a fall take upon imports. For most of our history, water has come from the Sierras (and on water. It’s also an opportunity to examine two of Los Angeles’ most im- from the Colorado River and Sacramento Bay Delta), while power has been portant political figures — the city’s mayor and council president. Finally, it’s generated by coal plants in Utah and Arizona. As Mayor Eric Garcetti notes a look at how power works, and doesn’t work, in Los Angeles — whether in this issue, the city has long been in the strange position of flushing out it’s the region’s infamous fragmentation and the problems that creates in rain that falls here while importing water from far away. water prices or the subtleties of political leadership in and around city hall. That’s changing. As these stories and interviews remind us, Los Angeles is a complicat- Guided in part by research featured in this issue, as well as directives ed place to solve big problems, and none is bigger than L.A.’s historic from the mayor, Los Angeles is committing itself to a water future very quest for water. -

57Th Socal Journalism Awards

FIFTY-SEVENTH ANNUAL5 SOUTHERN CALIFORNIA7 JOURNALISM AWARDS LOS ANGELES PRESS CLUB th 57 ANNUAL SOUTHERN CALIFORNIA 48 NOMINATIONS JOURNALISM AWARDS LOS ANGELES PRESS CLUB 57TH SOUTHERN CALIFORNIA JOURNALISM AWARDS WELCOME Dear Friends of L.A. Press Club, Well, you’ve done it this time. Yes, you really have! The Los Angeles Press Club’s 57th annual Southern California Journalism Awards are marked by a jaw-dropping, record-breaking number of submissions. They kept our sister Press Clubs across the country, who judge our annual competition, very busy and, no doubt, very impressed. So, as we welcome you this evening, know that even to arrive as a finalist is quite an accomplishment. Tonight in this very Biltmore ballroom, where Senator (and future President) John F. Kennedy held his first news conference after securing his party’s nomination, we honor the contributions of our colleagues. Some are no longer with Robert Kovacik us and we will dedicate this ceremony to three of the best among them: Al Martinez, Rick Orlov and Stan Chambers. The Los Angeles Press Club is where journalists and student journalists, working on all platforms, share their ideas and their concerns in our ever changing industry. If you are not a member, we invite you to join the oldest organization of its kind in Southern California. On behalf of our Board, we hope you have an opportunity this evening to reconnect with colleagues or to make some new connections. Together we will recognize our esteemed honorees: Willow Bay, Shane Smith and Vice News, the “CBS This Morning” team and representatives from Charlie Hebdo. -

William Brucher Dissertation Complete 5-13-12

ON THE EDGE OF THE PACIFIC RIM: CAPITALISM AND WORK ON THE LOS ANGELES WATERFRONT BY WILLIAM C. BRUCHER B.A., BATES COLLEGE, 2002 A.M., BROWN UNIVERSITY, 2007 A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY IN THE DEPARTMENT OF HISTORY AT BROWN UNIVERSITY PROVIDENCE, RHODE ISLAND MAY 2012 © Copyright 2012 by William C. Brucher This dissertation by William C. Brucher is accepted in its present form by the Department of History as satisfying the dissertation requirement for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. Date _______________ ________________________________ Elliott J. Gorn, Advisor Recommended to the Graduate Council Date _______________ ________________________________ Seth E. Rockman, Reader Date _______________ ________________________________ Robert O. Self, Reader Approved by the Graduate Council Date _______________ ________________________________ Peter M. Weber, Dean of the Graduate School iii Curriculum Vitae William C. Brucher was born on March 11, 1980, in Bangor, Maine and grew up in the nearby town of Bradford. He graduated with a B.A. in history from Bates College in Lewiston, Maine in 2002. From July 2002 through August 2006, he worked as a union organizer in the healthcare and human service industries for the Service Employees International Union and the Maine State Employees Association. He entered the Ph.D. program in history at Brown University in September 2006, earned his master’s degree in May 2007, and passed his qualifying exams in December 2008. While at Brown, he studied modern U.S. social and cultural history, transnational labor history, and modern Latin American history. He has served as a teaching assistant in a wide variety of early and modern U.S. -

Reuben W. Borough Papers, Ca

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/kt238nc5x7 No online items Finding Aid for the Reuben W. Borough papers, ca. 1880-1973 Processed by Jessica Frances Thomas in the Center for Primary Research and Training (CFPRT), with assistance from Megan Hahn Fraser and Yasmin Damshenas, June 2011; machine-readable finding aid created by Caroline Cubé. The processing of this collection was generously supported by Arcadia funds. UCLA Library Special Collections Room A1713, Charles E. Young Research Library Box 951575 Los Angeles, CA 90095-1575 Email: [email protected] URL: http://www.library.ucla.edu/libraries/special/scweb/ © 2012 The Regents of the University of California. All rights reserved. Finding Aid for the Reuben W. 927 1 Borough papers, ca. 1880-1973 Descriptive Summary Title: Reuben W. Borough papers Date (inclusive): ca. 1880-1973 Collection number: 927 Creator: Borough, Reuben W., 1883-1970 Extent: 98 boxes (approximately 49 linear ft.) Abstract: Reuben W. Borough (1883-1970) was active in the Populist movement in Los Angeles in the early 20th century. He was a newspaper reporter for the Los Angeles Record, worked on Upton Sinclair's EPIC (End Poverty in California) gubernatorial campaign, and served as a councilmember of the Municipal League of Los Angeles and as a board member of the Los Angeles Board of Public Works. He was a key organizer of the recall campaign that ousted Los Angeles Mayor Frank Shaw and elected Mayor Fletcher Bowron on a reform platform in 1938. He was a founding member of the Independent Progressive Party, and a life-long progressive proponent for labor, civil and political rights, peace, and the public ownership of power. -

United States Conference of Mayors

th The 84 Winter Meeting of The United States Conference of Mayors January 20-22, 2016 Washington, DC 1 #USCMwinter16 THE UNITED STATES CONFERENCE OF MAYORS 84th Winter Meeting January 20-22, 2016 Capital Hilton Hotel Washington, DC Draft of January 18, 2016 Unless otherwise noted, all plenary sessions, committee meetings, task force meetings, and social events are open to all mayors and other officially-registered attendees. WEDNESDAY, JANUARY 20 Registration 7:00 a.m. - 6:00 p.m. (Upper Lobby) Orientation for New Mayors and First Time Mayoral Attendees (Continental Breakfast) 8:00 a.m. - 9:00 a.m. (Statler ) The U.S. Conference of Mayors welcomes its new mayors, new members, and first time attendees to this informative session. Connect with fellow mayors and learn how to take full advantage of what the Conference has to offer. Presiding: TOM COCHRAN CEO and Executive Director The United States Conference of Mayors BRIAN C. WAHLER Mayor of Piscataway Chair, Membership Standing Committee 2 #USCMwinter16 WEDNESDAY, JANUARY 20 (Continued) Membership Standing Committee 9:00 a.m. - 10:00 a.m. (Federal A) Join us for an interactive panel discussion highlighting award-winning best practices and local mayoral priorities. Chair: BRIAN C. WAHLER Mayor of Piscataway Remarks: Mayor’s Business Council BRYAN K. BARNETT Mayor of Rochester Hills Solar Beaverton DENNY DOYLE Mayor of Beaverton City Energy Management Practices SHANE T. BEMIS Mayor of Gresham Council on Metro Economies and the New American City 9:00 a.m. - 10:00 a.m. (South American B) Chair: GREG FISCHER Mayor of Louisville Remarks: U.S.