I Prostrate to the Goddess Foe Destroyer •Fi Tibetan Buddhism and the (Mis)Naming of Venusian Features

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2018 Sakya Institute for Buddhist Studies Calendar.Xlsx

SAKYA INSTITUTE FOR BUDDHIST STUDIES 59 Church Street, Unit 3 Cambridge, MA 02138 sakya.net Registration is required by emaiL ([email protected]) Time Requirement Green Tara sadhana instruction and practice to accomplish mantra accumulation 26th; 7 - 9 pm Attendance on January 26th; Registration required. Continuing Vajrayogini sadhana practice to accomplish mantra accumulation and 23rd, 30th; 7 - 9 pm Vajrayogini Empowerment (Naropa Lineage); Registration required. instruction on Vajrayogini Self-Initiation practice Mangalam Yantra Yoga Level 6 25th; 7 - 9 pm Complete Yantra Level 5; Registration required. January Prajnaparamita Weekend Retreat 14th; 12 - 4 pm Open to public; $50; Registration required. Lion Headed Dakini Simhamukha Weekend Retreat 21st; 12 - 4 pm Open to public; $50; Registration required. Sitatapatra (White Umbrella) Weekend Retreat 28th; 12 - 4 pm Open to public; $50; Registration required. Meditation and Tara Puja 7th, 14th, 21st, 28th; 10 am - 12 pm Open to public Green Tara sadhana instruction and practice to accomplish mantra accumulation 2nd, 9th, 16th, 23rd; 7 - 9 pm Attendance on January 26th; Registration required. Continuing Vajrayogini sadhana practice to accomplish mantra accumulation and 6th, 13th, 20th, 27th; 7 - 9 pm Vajrayogini Empowerment (Naropa Lineage); Registration required. instruction on Vajrayogini Self-Initiation practice February Mangalam Yantra Yoga Level 6 1st, 8th, 15th, 22nd; 7 - 9 pm Complete Yantra Level 5; Registration required. Meditation and Tara Puja 4th, 11th, 18th, 25th; 10 am - 12 pm Open to public Green Tara sadhana instruction and practice to accomplish mantra accumulation 2nd, 9th, 16th, 23rd, 30th; 7 - 9 pm Attendance on January 26th; Registration required. Continuing Vajrayogini sadhana practice to accomplish mantra accumulation and 6th, 13th, 20th, 27th; 7 - 9 pm Vajrayogini Empowerment (Naropa Lineage); Registration required. -

Chariot of Faith Sekhar Guthog Tsuglag Khang, Drowolung

Chariot of Faith and Nectar for the Ears A Guide to: Sekhar Guthog Tsuglag Khang Drowolung Zang Phug Tagnya Foundation for the Preservation of the Mahayana Tradition 1632 SE 11th Avenue Portland, OR 97214 USA www.fpmt.org © 2014 Foundation for the Preservation of the Mahayana Tradition, Inc. All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system or technologies now known or developed, without permission in writing from the publisher. Set in Goudy Old Style 12/14.5 and BibleScrT. Cover image over Sekhar Guthog by Hugh Richardson, Wikimedia Com- mons. Printed in the USA. Practice Requirements: Anyone may read this text. Chariot of Faith and Nectar for the Ears 3 Chariot of Faith and Nectar for the Ears A Guide to Sekhar Guthog, Tsuglag Khang, Drowolung, Zang Phug, and Tagnya NAMO SARVA BUDDHA BODHISATTVAYA Homage to the buddhas and bodhisattvas! I prostrate to the lineage lamas, upholders of the precious Kagyu, The pioneers of the Vajrayana Vehicle That is the essence of all the teachings of Buddha Shakyamuni. Here I will write briefly the story of the holy place of Sekhar Guthog, together with its holy objects. The Glorious Bhagavan Hevajra manifested as Tombhi Heruka and set innumerable fortunate ones in the state of buddhahood in India. He then took rebirth in a Southern area of Tibet called Aus- picious Five Groups (Tashi Ding-Nga) at Pesar.1 Without discourage- ment, he went to many different parts of India where he met 108 lamas accomplished in study and practice, such as Maitripa and so forth. -

Healing and Self-Healing Through White Tara

HEALING AND SELF-HEALING THROUGH WHITE TARA Kyabje Gehlek Rimpoche Spring retreat teachings, The Netherlands 1995 Winter retreat vajrayana teachings, US 1996-7 A Jewel Heart Transcript ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Part I of this edition is the transcription of the teachings on White Tara, Healing and selfhealing, that Kyabje Gelek Rinpoche gave during the spring retreat 1995 in Nijmegen, The Netherlands. Part II are the vajrayana teachings on the practice of White Tara, taught by Rinpoche during the spring of 1995 in Nijmegen, a vajrayana weekend in Ann Arbor 1995, and the winterretreats 1996/97 en 1997/98 in the US. Part II is restricted; what is taught can only be practiced by those who’ve received full initiation in either Avalokiteshvara or in any maha annuttara yoga tantra. (A Tara long-life initiation – which actually is a blessing – is not what is meant here). Because of this restriction, part I has been published separately. The transcript is updated since the 4th edition. In particular it got a number of features that facilitate studying this worthwhile practice. A glossary, a list of literature and an index are provided. Images related to the teachings have been added. References to other literature have been made. Cross-references between the sutrayana- and the vajrayana part may help clarify difficulties. For easy study additional small headings have been made. The teachings of Part I were transcribed by several Jewel Heart friends in the Netherlands. The vajrayana teachings have been transcribed by Hartmut Sagolla. The drawing of Buddha Shakyamuni and those of the mudras were made by Marian van der Horst, those of the life-chakras by Piet Soeters. -

5 Pema Mandala Fall 06 11/21/06 12:02 PM Page 1

5 Pema Mandala Fall 06 11/21/06 12:02 PM Page 1 Fall/Winter 2006 5 Pema Mandala Fall 06 11/21/06 12:03 PM Page 2 Volume 5, Fall/Winter 2006 features A Publication of 3 Letter from the Venerable Khenpos Padmasambhava Buddhist Center Nyingma Lineage of Tibetan Buddhism 4 New Home for Ancient Treasures A long-awaited reliquary stupa is now at home at Founding Directors Ven. Khenchen Palden Sherab Rinpoche Padma Samye Ling, with precious relics inside. Ven. Khenpo Tsewang Dongyal Rinpoche 8 Starting to Practice Dream Yoga Rita Frizzell, Editor/Art Director Ani Lorraine, Contributing Editor More than merely resting, we can use the time we Beth Gongde, Copy Editor spend sleeping to truly benefit ourselves and others. Ann Helm, Teachings Editor Michael Nott, Advertising Director 13 Found in Translation Debra Jean Lambert, Administrative Assistant A student relates how she first met the Khenpos and Pema Mandala Office her experience translating Khenchen’s teachings on For subscriptions, change of address or Mipham Rinpoche. editorial submissions, please contact: Pema Mandala Magazine 1716A Linden Avenue 15 Ten Aspirations of a Bodhisattva Nashville, TN 37212 Translated for the 2006 Dzogchen Intensive. (615) 463-2374 • [email protected] 16 PBC Schedule for Fall 2006 / Winter 2007 Pema Mandala welcomes all contributions submitted for consideration. All accepted submissions will be edited appropriately 18 Namo Buddhaya, Namo Dharmaya, for publication in a magazine represent- Nama Sanghaya ing the Padmasambhava Buddhist Center. Please send submissions to the above A student reflects on a photograph and finds that it address. The deadline for the next issue is evokes more symbols than meet the eye. -

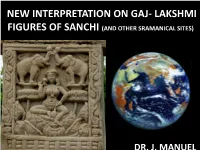

Female Deity of Sanchi on Lotus As Early Images of Bhu Devi J

NEW INTERPRETATION ON GAJ- LAKSHMI FIGURES OF SANCHI (AND OTHER SRAMANICAL SITES) nn DR. J. MANUEL THE BACK GROUND • INDRA RULED THE ROOST IN THE RGVEDIC AGE • OTHER GODS LIKE AGNI, SOMA, VARUN, SURYA BESIDES ASHVINIKUMARS, MARUTS WERE ALSO SPOKEN VERY HIGH IN THE LITERATURE • VISHNU IS ALSO KNOWN WITH INCREASING PROMINENCE SO MUCH SO IN THE LATE MANDALA 1 SUKT 22 A STRETCH OF SIX VERSES MENTION HIS POWER AND EFFECT • EVIDENTLY HIS GLORY WAS BEING FELT MORE AND MORE AS TIME PASSED • Mandal I Sukt 22 Richa 19 • Vishnu ki kripa say …….. Vishnu kay karyon ko dekho. Vay Indra kay upyukt sakha hai EVIDENTLY HIS GLORY WAS BEING FELT MORE AND MORE AS TIME PASSED AND HERO-GODS LIKE BALARAM AND VASUDEVA WERE ACCEPTED AS HIS INCARNATIONS • CHILAS IN PAKISTAN • AGATHOCLEUS COINS • TIKLA NEAR GWALIOR • ARE SOME EVIDENCE OF HERO-GODS BUT NOT VEDIC VISHNU IN SECOND CENTURY BC • There is the Kheri-Gujjar Figure also of the Therio anthropomorphic copper image BUT • FOR A LONG TIME INDRA CONTINUED TO HOLD THE FORT OF DOMINANCE • THIS IS SEEN IN EARLY SACRED LITERATURE AND ART ANTHROPOMORPHIC FIGURES • OF THE COPPER HOARD CULTURES ARE SAID TO BE INDRA FIGURES OF ABOUT 4000 YEARS OLD • THERE ARE MANY TENS OF FIGURES IN SRAMANICAL SITE OF INDRA INCLUDING AT SANCHI (MORE THAN 6) DATABLE TO 1ST CENTURY BCE • BUT NOT A SINGLE ONE OF VISHNU INDRA 5TH CENT. CE, SARNATH PARADOXICALLY • THERE ARE 100S OF REFERENCES OF VISHNU IN THE VEDAS AND EVEN MORE SO IN THE PURANIC PERIOD • WHILE THE REFERENCE OF LAKSHMI IS VERY FEW AND FAR IN BETWEEN • CURIOUSLY THE ART OF THE SUPPOSED LAXMI FIGURES ARE MANY TIMES MORE IN EARLY HISTORIC CONTEXT EVEN IN NON VAISHNAVA CONTEXT AND IN SUCH AREAS AS THE DECCAN AND AS SOUTH AS SRI- LANKA WHICH WAS THEN UNTOUCHED BY VAISHNAVISM NW INDIA TO SRI LANKA AZILISES COIN SHOWING GAJLAKSHMI IMAGERY 70-56 ADVENT OF VAISHNAVISM VISHNU HAD BY THE STARTING OF THE COMMON ERA BEGAN TO BECOME LARGER THAN INDRA BUT FOR THE BUDDHISTS INDRA CONTINUED TO BE DEPICTED IN RELATED STORIES CONTINUED FROM EARLIER TIMES; FROM BUDDHA. -

Proquest Dissertations

Daoxuan's vision of Jetavana: Imagining a utopian monastery in early Tang Item Type text; Dissertation-Reproduction (electronic) Authors Tan, Ai-Choo Zhi-Hui Publisher The University of Arizona. Rights Copyright © is held by the author. Digital access to this material is made possible by the University Libraries, University of Arizona. Further transmission, reproduction or presentation (such as public display or performance) of protected items is prohibited except with permission of the author. Download date 25/09/2021 09:09:41 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10150/280212 INFORMATION TO USERS This manuscript has been reproduced from the microfilm master. UMI films the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are In typewriter face, while others may be from any type of connputer printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are reproduced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand comer and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overiaps. ProQuest Information and Learning 300 North Zeeb Road, Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 USA 800-521-0600 DAOXUAN'S VISION OF JETAVANA: IMAGINING A UTOPIAN MONASTERY IN EARLY TANG by Zhihui Tan Copyright © Zhihui Tan 2002 A Dissertation Submitted to the Faculty of the DEPARTMENT OF EAST ASIAN STUDIES In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY In the Graduate College THE UNIVERSITY OF ARIZONA 2002 UMI Number: 3073263 Copyright 2002 by Tan, Zhihui Ai-Choo All rights reserved. -

And Daemonic Buddhism in India and Tibet

Florida State University Libraries Electronic Theses, Treatises and Dissertations The Graduate School 2012 The Raven and the Serpent: "The Great All- Pervading R#hula" Daemonic Buddhism in India and Tibet Cameron Bailey Follow this and additional works at the FSU Digital Library. For more information, please contact [email protected] THE FLORIDA STATE UNIVERSITY COLLEGE OF ARTS AND SCIENCES THE RAVEN AND THE SERPENT: “THE GREAT ALL-PERVADING RHULA” AND DMONIC BUDDHISM IN INDIA AND TIBET By CAMERON BAILEY A Thesis submitted to the Department of Religion in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Religion Degree Awarded: Spring Semester, 2012 Cameron Bailey defended this thesis on April 2, 2012. The members of the supervisory committee were: Bryan Cuevas Professor Directing Thesis Jimmy Yu Committee Member Kathleen Erndl Committee Member The Graduate School has verified and approved the above-named committee members, and certifies that the thesis has been approved in accordance with university requirements. ii For my parents iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to thank, first and foremost, my adviser Dr. Bryan Cuevas who has guided me through the process of writing this thesis, and introduced me to most of the sources used in it. My growth as a scholar is almost entirely due to his influence. I would also like to thank Dr. Jimmy Yu, Dr. Kathleen Erndl, and Dr. Joseph Hellweg. If there is anything worthwhile in this work, it is undoubtedly due to their instruction. I also wish to thank my former undergraduate advisor at Indiana University, Dr. Richard Nance, who inspired me to become a scholar of Buddhism. -

Brief History of Dzogchen

Brief History of Dzogchen This is the printer-friendly version of: http: / / www.berzinarchives.com / web / en / archives / advanced / dzogchen / basic_points / brief_history_dzogchen.html Alexander Berzin November 10-12, 2000 Introduction Dzogchen (rdzogs-chen), the great completeness, is a Mahayana system of practice leading to enlightenment and involves a view of reality, way of meditating, and way of behaving (lta-sgom-spyod gsum). It is found earliest in the Nyingma and Bon (pre-Buddhist) traditions. Bon, according to its own description, was founded in Tazig (sTag-gzig), an Iranian cultural area of Central Asia, by Shenrab Miwo (gShen-rab mi-bo) and was brought to Zhang-zhung (Western Tibet) in the eleventh century BCE. There is no way to validate this scientifically. Buddha lived in the sixth century BCE in India. The Introduction of Pre-Nyingma Buddhism and Zhang-zhung Rites to Central Tibet Zhang-zhung was conquered by Yarlung (Central Tibet) in 645 CE. The Yarlung Emperor Songtsen-gampo (Srong-btsan sgam-po) had wives not only from the Chinese and Nepali royal families (both of whom brought a few Buddhist texts and statues), but also from the royal family of Zhang-zhung. The court adopted Zhang-zhung (Bon) burial rituals and animal sacrifice, although Bon says that animal sacrifice was native to Tibet, not a Bon custom. The Emperor built thirteen Buddhist temples around Tibet and Bhutan, but did not found any monasteries. This pre-Nyingma phase of Buddhism in Central Tibet did not have dzogchen teachings. In fact, it is difficult to ascertain what level of Buddhist teachings and practice were introduced. -

South-Indian Images of Gods and Goddesses

ASIA II MB- • ! 00/ CORNELL UNIVERSITY* LIBRARY Date Due >Sf{JviVre > -&h—2 RftPP )9 -Af v^r- tjy J A j£ **'lr *7 i !! in ^_ fc-£r Pg&diJBii'* Cornell University Library NB 1001.K92 South-indian images of gods and goddesse 3 1924 022 943 447 AGENTS FOR THE SALE OF MADRAS GOVERNMENT PUBLICATIONS. IN INDIA. A. G. Barraud & Co. (Late A. J. Combridge & Co.)> Madras. R. Cambrav & Co., Calcutta. E. M. Gopalakrishna Kone, Pudumantapam, Madura. Higginbothams (Ltd.), Mount Road, Madras. V. Kalyanarama Iyer & Co., Esplanade, Madras. G. C. Loganatham Brothers, Madras. S. Murthv & Co., Madras. G. A. Natesan & Co., Madras. The Superintendent, Nazair Kanun Hind Press, Allahabad. P. R. Rama Iyer & Co., Madras. D. B. Taraporevala Sons & Co., Bombay. Thacker & Co. (Ltd.), Bombay. Thacker, Spink & Co., Calcutta. S. Vas & Co., Madras. S.P.C.K. Press, Madras. IN THE UNITED KINGDOM. B. H. Blackwell, 50 and 51, Broad Street, Oxford. Constable & Co., 10, Orange Street, Leicester Square, London, W.C. Deighton, Bell & Co. (Ltd.), Cambridge. \ T. Fisher Unwin (Ltd.), j, Adelphi Terrace, London, W.C. Grindlay & Co., 54, Parliament Street, London, S.W. Kegan Paul, Trench, Trubner & Co. (Ltd.), 68—74, iCarter Lane, London, E.C. and 25, Museum Street, London, W.C. Henry S. King & Co., 65, Cornhill, London, E.C. X P. S. King & Son, 2 and 4, Great Smith Street, Westminster, London, S.W.- Luzac & Co., 46, Great Russell Street, London, W.C. B. Quaritch, 11, Grafton Street, New Bond Street, London, W. W. Thacker & Co.^f*Cre<d Lane, London, E.O? *' Oliver and Boyd, Tweeddale Court, Edinburgh. -

Zanabazar (1635-1723): Vajrayāna Art and the State in Medieval Mongolia

Zanabazar (1635-1723): Vajrayāna Art and the State in Medieval Mongolia Uranchimeg Tsultem ___________________________________________________________________________________ This is the author’s manuscript of the article published in the final edited form as: Tsultem, U. (2015). Zanabazar (1635–1723): Vajrayāna Art and the State in Medieval Mongolia. In Buddhism in Mongolian History, Culture, and Society (pp. 116–136). Introduction The First Jebtsundamba Khutukhtu (T. rJe btsun dam pa sprul sku) Öndör Gegeen Zanabazar is the most celebrated person in the history of Mongolian Buddhism, whose activities marked the important moments in the Mongolian politics, history, and cultural life, as they heralded the new era for the Mongols. His masterpieces of Buddhist sculptures exhibit a sophisticated accomplishment of the Buddhist iconometrical canon, a craftsmanship of the highest quality, and a refined, yet unfettered virtuosity. Zanabazar is believed to have single-handedly brought the tradition of Vajrayāna Buddhism to the late medieval Mongolia. Buddhist rituals, texts, temple construction, Buddhist art, and even designs for Mongolian monastic robes are all attributed to his genius. He also introduced to Mongolia the artistic forms of Buddhist deities, such as the Five Tath›gatas, Maitreya, Twenty-One T›r›s, Vajradhara, Vajrasattva, and others. They constitute a salient hallmark of his careful selection of the deities, their forms, and their representation. These deities and their forms of representation were unique to Zanabazar. Zanabazar is also accredited with building his main Buddhist settlement Urga (Örgöö), a mobile camp that was to reach out the nomadic communities in various areas of Mongolia and spread Buddhism among them. In the course of time, Urga was strategically developed into the main Khalkha monastery, Ikh Khüree, while maintaining its mobility until 1855. -

A Sorrowful Song to Palden Lhamo Kün-Kyab Tro

A SORROWFUL SONG TO PALDEN LHAMO KÜN-KYAB TRO- DREL A PRAISE BY HIS HOLINESS THE DALAI LAMA Expanse of great bliss, all-pervading, free from elaborations, with either angry or desirous forms related to those to be subdued. You overpower the whole apparent world, samsara and nirvana. Sole mother, lady victorious over the three worlds, please pay attention here and now! During numberless eons, By relying upon and accustoming yourself to the extensive conduct of the bodhisattvas, which others find difficult to follow, you obtained the power of the sublime vajra enlightenment; loving mother, you watch and don’t miss the [right] time. The winds of conceptuality dissolve into space. Vajra-dance of the mind that produces all the animate and inanimate world, as the sole friend yielding the pleasures of existence and peace, having conquered them all, you are well praised as the triumphant mother. By heroically guarding the Dharma and dharma- holders, with the four types of actions, flashing like lightning, You soar up openly, like the full moon in the midst of a garland of powerful Dharma protectors. When from the troublesome nature of this most degenerated time The hosts of evil omens — desire, anger, ignorance — increasingly rise, even then your power is unimpeded, sharp, swift and limitless. How wonderful! Longingly remembering you, O Goddess, from my heart, I confess my broken vows and satisfy all your pleasures. Having enthroned you as the supreme protector, greatest among the great, accomplish your appointed tasks with unflinching energy! Fierce protecting deities and your retinues who, in accordance with the instructions of the supreme siddha, the lotus-born vajra, and by the power of karma and prayers, have a close connection as guardians of Tibet, heighten your majesty and increase your powers! All beings in the country of Tibet, although destroyed by the enemy and tormented by unbearable suffering, abide in the constant hope of glorious freedom. -

The Ecumenical Buddhist

The Ecumenical Buddhist A Publication of the Ecumenical Buddhist Society of Little Rock October 2016, Volume 26, Number 5 Dance Party & Anna Cox’s Retirement Party Potluck for EBS Volunteers Thursday November 17 6-9 p.m. Saturday, October 29 Anna Cox, one of the founding members of EBS, recently 6-9 p.m. retired from active participation in our community. She has Before they leave for Idaho, the EBS Board wanted to thank played a central role at EBS from the beginning, and we will Eileen Oldag and Tom Neale for their many years of volunteer miss her. support and financial contributions to EBS. We will miss them, Anna remained dedicated to the EBS and we wish them all the best. community for 25 years. She led the Please come help us celebrate Eileen and Tom and all the Vajrayana practices, and worked tire- other wonderful EBS volunteers and supporters with a volun- lessly to pass on the lineage teachings teer appreciation dance party and potluck supper on Saturday of Lama Tharchin Rinpoche. We are night, October 29, from 6-9 p.m. grateful for her unwavering energy, Bring your favorite dance music! kindness, and friendship. Anna also represented Buddhism beyond EBS in interfaith Bring your best vegetarian food! groups and within the prisons and social justice movements. And don’t forget to bring your best dance moves! Countless people have witnessed the presence of the Bud- dha—kind, compassionate, clear—in their encounters with For almost a decade, Tom and Eileen have Anna. led the Mindfulness practice group follow- Please join us in celebrating Anna and all of her accomplish- ing in the tradition of Thich Nhat Hanh.