Proof Cover Sheet

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Charles Darwin: a Companion

CHARLES DARWIN: A COMPANION Charles Darwin aged 59. Reproduction of a photograph by Julia Margaret Cameron, original 13 x 10 inches, taken at Dumbola Lodge, Freshwater, Isle of Wight in July 1869. The original print is signed and authenticated by Mrs Cameron and also signed by Darwin. It bears Colnaghi's blind embossed registration. [page 3] CHARLES DARWIN A Companion by R. B. FREEMAN Department of Zoology University College London DAWSON [page 4] First published in 1978 © R. B. Freeman 1978 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise without the permission of the publisher: Wm Dawson & Sons Ltd, Cannon House Folkestone, Kent, England Archon Books, The Shoe String Press, Inc 995 Sherman Avenue, Hamden, Connecticut 06514 USA British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data Freeman, Richard Broke. Charles Darwin. 1. Darwin, Charles – Dictionaries, indexes, etc. 575′. 0092′4 QH31. D2 ISBN 0–7129–0901–X Archon ISBN 0–208–01739–9 LC 78–40928 Filmset in 11/12 pt Bembo Printed and bound in Great Britain by W & J Mackay Limited, Chatham [page 5] CONTENTS List of Illustrations 6 Introduction 7 Acknowledgements 10 Abbreviations 11 Text 17–309 [page 6] LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS Charles Darwin aged 59 Frontispiece From a photograph by Julia Margaret Cameron Skeleton Pedigree of Charles Robert Darwin 66 Pedigree to show Charles Robert Darwin's Relationship to his Wife Emma 67 Wedgwood Pedigree of Robert Darwin's Children and Grandchildren 68 Arms and Crest of Robert Waring Darwin 69 Research Notes on Insectivorous Plants 1860 90 Charles Darwin's Full Signature 91 [page 7] INTRODUCTION THIS Companion is about Charles Darwin the man: it is not about evolution by natural selection, nor is it about any other of his theoretical or experimental work. -

DOCTORAL THESIS Vernon Lushington : Practising Positivism

DOCTORAL THESIS Vernon Lushington : Practising Positivism Taylor, David Award date: 2010 General rights Copyright and moral rights for the publications made accessible in the public portal are retained by the authors and/or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. • Users may download and print one copy of any publication from the public portal for the purpose of private study or research. • You may not further distribute the material or use it for any profit-making activity or commercial gain • You may freely distribute the URL identifying the publication in the public portal ? Take down policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact us providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. Download date: 29. Sep. 2021 Vernon Lushington : Practising Positivism by David C. Taylor, MA, FSA A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of PhD School of Arts Roehampton University 2010 Abstract Vernon Lushington (1832-1912) was a leading Positivist and disciple of Comte's Religion of Humanity. In The Religion of Humanity: The Impact of Comtean Positivism on Victorian Britain T.R. Wright observed that “the inner struggles of many of [Comte's] English disciples, so amply documented in their note books, letters, and diaries, have not so far received the close sympathetic treatment they deserve.” Material from a previously little known and un-researched archive of the Lushington family now makes possible such a study. -

Ethical Record the Proceedings of the South Place Ethical Society Vol

Ethical Record The Proceedings of the South Place Ethical Society Vol. 115 No. 10 £1.50 December 2010 IS THE POPE ON A SLIPPERY SLOPE? As a thoughtful person, the Pope is concerned that males involved in certain activities might inadvertently spread the AIDS virus to their male friends. He has therefore apparently authorised them to employ condoms, thereby contradicting his organisation's propaganda that these articles are ineffective for this purpose. He also knows that the said activities are most unlikely to result in conception! The obvious next point to consider is the position of a woman whose husband may have the AIDS virus. The Pope has not authorised that the husband's virus should be similarly confined and his wife protected from danger. The Pope apparently considers that the divine requirement to conceive takes precedence, even if the child and its mother contract AIDS as a result. For how long can this absurd contradiction be maintained? VERNON LUSHINGTON, THE CRISIS OF FAITH AND THE ETII1CS OF POSITIVISM David Taylor 3 THE SPIRIT LEVEL DELUSION Christopher Snowdon 10 REVIEW: HUMANISM: A BEGINNER'S GUIDE by Peter Cave Charles Rudd 13 CLIMATE CHANGE, DEMOCRACY AND HUMAN NATURE Marek Kohn 15 VIEWPOINTS Colin Mills. Jim Tazewell 22 ETHICAL SOCIETY EVENTS 24 Centre for Inquiry UK and South Place Ethical Society present THE ROOT CAUSES OF THE HOLOCAUST What caused the Holocaust? What was the role of the Enlightenment? What role did religion play in causing, or trying to halt, the Holocaust? 1030 Registration 1100 Jonathan Glover 1200 David Ranan 1300 A .C. -

TRINITY COLLEGE Cambridge Trinity College Cambridge College Trinity Annual Record Annual

2016 TRINITY COLLEGE cambridge trinity college cambridge annual record annual record 2016 Trinity College Cambridge Annual Record 2015–2016 Trinity College Cambridge CB2 1TQ Telephone: 01223 338400 e-mail: [email protected] website: www.trin.cam.ac.uk Contents 5 Editorial 11 Commemoration 12 Chapel Address 15 The Health of the College 18 The Master’s Response on Behalf of the College 25 Alumni Relations & Development 26 Alumni Relations and Associations 37 Dining Privileges 38 Annual Gatherings 39 Alumni Achievements CONTENTS 44 Donations to the College Library 47 College Activities 48 First & Third Trinity Boat Club 53 Field Clubs 71 Students’ Union and Societies 80 College Choir 83 Features 84 Hermes 86 Inside a Pirate’s Cookbook 93 “… Through a Glass Darkly…” 102 Robert Smith, John Harrison, and a College Clock 109 ‘We need to talk about Erskine’ 117 My time as advisor to the BBC’s War and Peace TRINITY ANNUAL RECORD 2016 | 3 123 Fellows, Staff, and Students 124 The Master and Fellows 139 Appointments and Distinctions 141 In Memoriam 155 A Ninetieth Birthday Speech 158 An Eightieth Birthday Speech 167 College Notes 181 The Register 182 In Memoriam 186 Addresses wanted CONTENTS TRINITY ANNUAL RECORD 2016 | 4 Editorial It is with some trepidation that I step into Boyd Hilton’s shoes and take on the editorship of this journal. He managed the transition to ‘glossy’ with flair and panache. As historian of the College and sometime holder of many of its working offices, he also brought a knowledge of its past and an understanding of its mysteries that I am unable to match. -

Teaching Eighteenth-Century French Literature: the Good, the Bad and the Ugly

Eighteenth-Century Modernities: Present Contributions and Potential Future Projects from EC/ASECS (The 2014 EC/ASECS Presidential Address) by Christine Clark-Evans It never occurred to me in my research, writing, and musings that there would be two hit, cable television programs centered in space, time, and mythic cultural metanarrative about 18th-century America, focusing on the 1760s through the 1770s, before the U.S. became the U.S. One program, Sleepy Hollow on the FOX channel (not the 1999 Johnny Depp film) represents a pre- Revolutionary supernatural war drama in which the characters have 21st-century social, moral, and family crises. Added for good measure to several threads very similar to Washington Irving’s “Legend of Sleepy Hollow” story are a ferocious headless horseman, representing all that is evil in the form of a grotesque decapitated man-demon, who is determined to destroy the tall, handsome, newly reawakened Rip-Van-Winkle-like Ichabod Crane and the lethal, FBI-trained, diminutive beauty Lt. Abigail Mills. These last two are soldiers for the politically and spiritually righteous in both worlds, who themselves are fatefully inseparable as the only witnesses/defenders against apocalyptic doom. While the main characters in Sleepy Hollow on television act out their protracted, violent conflict against natural and supernatural forces, they also have their own high production-level, R & B-laced, online music video entitled “Ghost.” The throaty feminine voice rocks back and forth to accompany the deft montage of dramatic and frightening scenes of these talented, beautiful men and these talented, beautiful women, who use as their weapons American patriotism, religious faith, science, and wizardry. -

Introduction Chapter 1

Notes Introduction 1. Allan Ramsay, ‘Verses by the Celebrated Allan Ramsay to his Son. On his Drawing a Fine Gentleman’s Picture’, in The Scarborough Miscellany for the Year 1732, 2nd edn (London: Wilford, 1734), pp. 20–22 (p. 20, p. 21, p. 21). 2. See Iain Gordon Brown, Poet & Painter, Allan Ramsay, Father and Son, 1684–1784 (Edinburgh: National Library of Scotland, 1984). 3. When considering works produced prior to the formation of the United Kingdom in 1801, I have followed in this study the eighteenth-century prac- tice of using ‘united kingdom’ in lower case as a synonym for Great Britain. 4. See, respectively, Kurt Wittig, The Scottish Tradition in Literature (London: Oliver and Boyd, 1958); G. Gregory Smith, Scottish Literature: Character and Influence (London: Macmillan, 1919); Hugh MacDiarmid, A Drunk Man Looks at the Thistle, ed. by Kenneth Buthlay (Edinburgh: Scottish Academic Press, 1988); David Craig, Scottish Literature and the Scottish People, 1680–1830 (London: Chatto & Windus, 1961); David Daiches, The Paradox of Scottish Culture: The Eighteenth-Century Experience (London: Oxford University Press, 1964); Kenneth Simpson, The Protean Scot: The Crisis of Identity in Eighteenth-Century Scottish Literature (Aberdeen: Aberdeen University Press, 1988); Robert Crawford, Devolving English Literature (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1992); Murray Pittock, Poetry and Jacobite Politics in Eighteenth- Century Britain and Ireland (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1994) and idem, Scottish and Irish Romanticism (Oxford: Oxford University -

1 the Public Life of a Twentieth Century Princess Princess Mary Princess Royal and Countess of Harewood Wendy Marion Tebble

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by SAS-SPACE 1 The Public Life of a Twentieth Century Princess Princess Mary Princess Royal and Countess of Harewood Wendy Marion Tebble, Institute of Historical Research Thesis submitted for Degree of Master of Philosophy, 2018 2 Table of Contents Abstract 3 Acknowledgements 5 Abbreviations 7 Acronyms 8 Chapters 9 Conclusion 136 Bibliography 155 3 Abstract The histiography on Princess Mary is conspicuous by its absence. No official account of her long public life, from 1914 to 1965, has been written and published since 1922, when the princess was aged twenty-five, and about to be married. The only daughter of King George V, she was one of the chief protagonists in his plans to include his children in his efforts to engage the monarchy, and the royal family, more deeply and closely with the people of the United Kingdom. This was a time when women were striving to enter public life more fully, a role hitherto denied to them. The king’s decision was largely prompted by the sacrifices of so many during the First World War; the fall of Czar Nicholas of Russia; the growth of socialism; and the dangers these events may present to the longevity of the monarchy in a disaffected kingdom. Princess Mary’s public life helps to answer the question of what role royal women, then and in the future, are able to play in support of the monarchy. It was a time when for the most part careers of any kind were not open to women, royal or otherwise, and the majority had yet to gain the right to vote. -

The Oxford Dictionary of National Biography

Impact case study (REF3b) Institution: University of Oxford Unit of Assessment: UOA30 Title of case study: The Oxford Dictionary of National Biography 1. Summary of the impact (indicative maximum 100 words) Public understanding of the national past has been expanded by the creation, updating, and widespread use of the Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (ODNB). It is the most comprehensive biographical reference work in the English language and includes (in May 2013) biographies of 58,661 people over two millennia. The ODNB is the ‘national record’ of those who have shaped the British past, and disseminates knowledge while also prompting and enhancing public debate. The Dictionary informs teaching and research in HEIs worldwide, and is used routinely by family and local historians, public librarians, archivists, museum and gallery curators, schools, broadcasters, and journalists. The wider cultural benefit of this fundamental research resource has been advanced by a programme of online public engagement. 2. Underpinning research (indicative maximum 500 words) The ODNB was commissioned in 1992 as a research project of the Oxford History Faculty and was published by Oxford University Press in print and online in 2004; subsequently it has been extended online with 3 annual updates and the publication of two further print volumes. Since 2005, an important part of the editors’ work has been to update the Dictionary’s 56,000 existing entries in the light of new research, keeping biographies in-step with recent publications and new digitized primary sources. In this way, editors create and maintain a resource that is comprehensive, authoritative, and balanced, as well as publishing new historical research. -

![Journal of Interdisciplinary History of Ideas, 16 | 2019 [Online], Online Since 31 December 2019, Connection on 30 July 2020](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/2447/journal-of-interdisciplinary-history-of-ideas-16-2019-online-online-since-31-december-2019-connection-on-30-july-2020-1392447.webp)

Journal of Interdisciplinary History of Ideas, 16 | 2019 [Online], Online Since 31 December 2019, Connection on 30 July 2020

Journal of Interdisciplinary History of Ideas 16 | 2019 Varia Electronic version URL: http://journals.openedition.org/jihi/276 ISSN: 2280-8574 Publisher GISI – UniTo Electronic reference Journal of Interdisciplinary History of Ideas, 16 | 2019 [Online], Online since 31 December 2019, connection on 30 July 2020. URL : http://journals.openedition.org/jihi/276 This text was automatically generated on 30 July 2020. Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International Public License 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS Éditorial Manuela Albertone and Enrico Pasini Articles Rendering Sociology. On the Utopian Positivism of Harriet Martineau and the ‘Mumbo Jumbo Club’ Matthew Wilson Individualism and Social Change An Unexpected Theoretical Dilemma in Marxian Analysis Vitantonio Gioia Notes Introduction to the Open Peer-Reviewed Section on DR2 Methodology Examples Guido Bonino, Paolo Tripodi and Enrico Pasini Exploring Knowledge Dynamics in the Humanities Two Science Mapping Experiments Eugenio Petrovich and Emiliano Tolusso Reading Wittgenstein Between the Texts Marco Santoro, Massimo Airoldi and Emanuela Riviera Two Quantitative Researches in the History of Philosophy Some Down-to-Earth and Haphazard Methodological Reflections Guido Bonino, Paolo Maffezioli and Paolo Tripodi Book Reviews Becoming a New Self: Practices of Belief in Early Modern Catholicism, Moshe Sluhovsky Lucia Delaini Journal of Interdisciplinary History of Ideas, 16 | 2019 2 Éditorial Manuela Albertone et Enrico Pasini 1 Le numéro qu’on va présenter à nos lecteurs donne deux expressions d’une histoire interdisciplinaire des idées, qui touche d’une façon différente à la dimension sociologique. Une nouvelle attention au jeune Marx est axée sur le rapport entre la formation de l’individualisme et le contexte historique, que l’orthodoxie marxiste a négligé, faute d’une connaissance directe des écrits de la période de la jeunesse du philosophe allemand. -

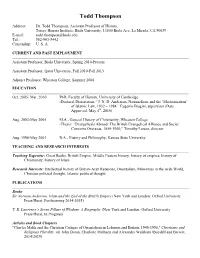

Todd Thompson

Todd Thompson Address: Dr. Todd Thompson, Assistant Professor of History, Torrey Honors Institute, Biola University, 13800 Biola Ave, La Mirada, CA 90639 E-mail: [email protected] Tel.: 562-903-5442 Citizenship: U. S. A. CURRENT AND PAST EMPLOYMENT Assistant Professor, Biola University, Spring 2014-Present Assistant Professor, Qatar University, Fall 2010-Fall 2013 Adjunct Professor, Wheaton College, Summer 2008 EDUCATION Oct. 2005- Mar. 2010 PhD, Faculty of History, University of Cambridge -Doctoral Dissertation: “J. N. D. Anderson, Nationalism, and the ‘Modernisation’ of Islamic Law, 1932 – 1984,” Eugenio Biagini, supervisor (Date Approved: May 4th, 2010) Aug. 2003-May 2005 M.A., General History of Christianity, Wheaton College -Thesis: “Evangelicals Abroad: The British Evangelical Alliance and Social Concerns Overseas, 1850-1900,” Timothy Larsen, director Aug. 1998-May 2003 B.A., History and Philosophy, Kansas State University TEACHING AND RESEARCH INTERESTS Teaching Expertise: Great Books, British Empire, Middle Eastern history, history of empires, history of Christianity, history of Islam Research Interests: Intellectual history of British-Arab Relations, Orientalism, Minorities in the Arab World, Christian political thought, Islamic political thought PUBLICATIONS Books Sir Norman Anderson, Islam and the End of the British Empire (New York and London: Oxford University Press/Hurst, Forthcoming 2014-2015) T. E. Lawrence’s Seven Pillars of Wisdom: A Biography (New York and London: Oxford University Press/Hurst, In Progress) Articles and Book Chapters "Charles Malik and the Christian Critique of Orientalism in Lebanon and Britain, 1945-1956," Christians and Religious Plurality, ed. John Doran, Charlotte Methuen and Alexandra Walsham (Boydell and Brewer, 2014/2015) "Albert Hourani, Christian Minorities and the Spiritual Dimension of Britain's Problem in Palestine, 1938- 1947," in Christians and the Middle East Conflict, ed. -

Funded by a Grant from the Arts and Humanities Research Board)

This document was supplied by the depositor and has been modified by AHDS History McGregor, Goldman and White's Catalogue of the Published Papers of the N.A.P.S.S. (funded by a grant from the Arts and Humanities Research Board) 1. The National Association for the Promotion of Social Science: An Introduction The National Association for the Promotion of Social Science, otherwise known as the Social Science Association, was the pre-eminent forum for the discussion of social questions and the dissemination of knowledge about society in mid-Victorian Britain. Founded in 1857 and active until 1884, it provided expert guidance to policy-makers and politicians in the era of Gladstone and Disraeli (Lawrence Goldman, Science, Reform and Politics in Victorian Britain. The Social Science Association 1857-1886 (Cambridge, 2002)). Foundation The Association was constructed out of several different organisations and campaigns in the mid- 1850s. Rather than undertaking research and lobbying government on single issues, social reformers then believed that a pooling of resources and ideas in a single, large and multi-faceted forum would assist their various interests and the cause of reform in general. The National Association brought together law reformers from the Society for Promoting the Amendment of the Law (which had been founded in 1844); penal reformers from the National Reformatory Union who were focused on the reformation of young offenders; and the pioneering feminists of the Langham Place Circle in London who, from 1855, led a campaign to reform the laws of property as they affected women in marriage, and who subsequently extended their critique to many other aspects of the social, economic and political status of women in Victorian Britain. -

Aristocratic Women at the Late Elizabethan Court: Politics, Patronage and Power

Aristocratic Women at the Late Elizabethan Court: Politics, Patronage and Power Joanne Lee Hocking School of Humanities, Department of History University of Adelaide November 2015 Table of Contents Abstract i Thesis declaration iii Acknowledgments iv List of Abbreviations v Chapter 1 Introduction 1 Chapter 2 The Political Context, 1580-1603 28 Chapter 3 The Politics of Female Agency: 54 Anne Dudley, Countess of Warwick Chapter 4 The Politics of Family and Faction: 132 Anne, Lady Bacon and Elizabeth, Lady Russell Chapter 5 The Politics of Favour: the Essex Women 195 Chapter 6 Conclusion 265 Appendices Appendix A – the Russell family 273 Appendix B – the Dudley family 274 Appendix C – the Cooke family 275 Appendix D – the Devereux family 276 Appendix E – Countess of Warwick’s 277 Patronage Network Appendix F –Countess of Warwick’s will 292 Bibliography 305 Abstract This thesis examines the power of aristocratic women in politics and patronage in the final years of the Elizabethan court (1580 to 1603). Substantial archival sources are analysed to evaluate the concepts of female political agency discussed in scholarly literature, including women’s roles in politics, within families, in networks and as part of the court patronage system. A case study methodology is used to examine the lives and careers of specific aristocratic women in three spheres of court politics – the politics of female agency, the politics of family and faction, and the politics of favour. The first case study looks at Elizabeth’s long-serving lady-in-waiting, Anne Dudley, Countess of Warwick, and demonstrates that female political agents harnessed multiple sources of agency to exercise power at court on behalf of dense patronage networks.