Compartment Syndrome Booklet

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Retrospective Review of Gunshot Injuries to the Foot & Ankle

Retrospective Review of Gunshot Injuries to the Foot & Ankle; A New Classification and Treatment Protocol Richard Bauer, DPM (PGY-4); Eliezer Eisenberger, DPM (PGY-4); Faculty: Emilio Goez, DPM, FACFAS St. Barnabas Health System; Regional Level-1 Trauma Center - Bronx, NY Statement of Purpose Literature Review Results Analysis & Discussion cont... The U.S. has an average of 30,900 gun related deaths per year and an additional Much of the literature related to gunshot wounds is adapted from high velocity projectile combat injuries, however most There were a total of twelve (12) patients who met our inclusion criteria that were treated for isolated gunshot wounds to the We have divided the anatomic locations into “zones.” Zone 1 refers to the digits in their entirety up to and including the 69,863 non-fatal gun related injuries were reported in 20081. Several studies have civilian gunshot wounds are resultant from low velocity (<300 m/sec) firearms1,3,4. Gunshot wounds to the lower extremity foot and ankle between the dates of 8/1/2010-11/1/2012. All patients were male with a mean age of 24.25 years. All injuries metatarsophalangeal joints (MPJ‟s), Zone 2 refers to the metatarsal and tarsal bones and Zone 3 refers to the calcaneus, reviewed treatment protocols for gunshot injuries to bone and related structures, represent approximately 63% of all gunshot related injuries, however only a fraction of these are located in the foot & ankle4. were classified as low velocity gunshot wounds. Four patients (33.3%) presented with isolated digital injury, three (25%) talus, tibia and fibula. -

Identification and Surgical Management of Upper Arm and Forearm Compartment Syndrome

Open Access Case Report DOI: 10.7759/cureus.5862 Identification and Surgical Management of Upper Arm and Forearm Compartment Syndrome Adel Hanandeh 1 , Vishnu R. Mani 2 , Paul Bauer 1 , Alexius Ramcharan 3 , Brian Donaldson 1 1. General Surgery, Columbia University College of Physicians and Surgeons at Harlem Hospital Center, New York, USA 2. Surgery, Columbia University College of Physicians and Surgeons at Harlem Hospital Center, New York, USA 3. Surgery, Harlem Hospital Center, New York, USA Corresponding author: Adel Hanandeh, [email protected] Abstract Extremity muscles are grouped and divided by strong fascial membranes into compartments. Multiple pathological processes can result in an increase in the pressure within a muscle compartment. An increase in the compartment pressure beyond the adequate perfusion pressure has the potential to cause extremity compartment syndrome. There are multiple sites where compartment syndrome can occur. In this article, an arm and forearm compartment syndrome ensued secondary to a minor crushing injury that lead to supracondylar and medial epicondylar non-displaced fractures. A pure motor radial and ulnar nerve deficits noted on presentation, worsened with progression of the compartment syndrome. Ultimately, a surgical fasciotomy was carried out to release all compartments of the right upper arm and forearm. Categories: General Surgery, Orthopedics, Anatomy Keywords: upper arm compartment syndrome, fasciotomy, forearm compartment syndrome, condylar fracture, pediatric supracondylar humerus fracture Introduction In 1872, the first description of compartment syndrome was published by Richard von Volkmann. His publication described an irreversible contracture of muscles due to ischemic process resulting in the first documented nerve injury and contracture from compartment syndrome. -

Exposure of the Forearm and Distal Radius

Exposure of the Forearm and Distal Radius Melissa A. Klausmeyer, MDa, Chaitanya Mudgal, MDb,* KEYWORDS Henry approach Thompson approach Flexor carpi radialis approach Dorsal distal radius approach Distal radius approach KEY POINTS The use of internervous planes allow access to the underlying bone without risk of denervating the overlying muscles. The choice of approach is based on the injury pattern and need for exposure. The Henry and Thompson approaches are useful for radial shaft fractures. The distal radius can be approached volarly through the flexor carpi radialis (FCR) approach or dorsally through the extended Thompson approach. The extended FCR approach is useful for intraarticular fractures of the distal radius as well as mal- unions and subacute fractures. INTRODUCTION ANATOMY OF THE FOREARM Muscles Safe operative approaches to the bones of the forearm and wrist include the use of internervous The muscles of the forearm are split into 4 compart- planes. These planes lie between muscles that ments: The superficial volar, the deep volar, the are innervated by different nerves. By utilizing extensor, and the mobile wad (Table 1). The median these planes for dissection, extensive mobilization nerve supplies all of the volar muscles of the forearm of muscles and therefore large areas of exposure except the ulnar half of the flexor digitorum profun- may be obtained without the risk of muscle dus and the flexor carpi ulnaris that are supplied denervation. by the ulnar nerve. The radial nerve proper supplies A successful operative plan also must include the brachioradialis and extensor carpi radialis lon- consideration of the soft tissues, particularly gus. -

Treatment of Established Volkmann's Contracture*

~hop. Acta Treatment of Established Volkmann’sContracture* BY KENYA TSUGE, M.D.’J’, HIROSHIMA, JAPAN ldon, From the Department of Orthopaedic Surgery, Hiroshima Universi~.’ 1-76, School of Medicine, Hiroshima 38. The disease first described by Volkmann in 1881 is the extent of the disease: mild, moderate, and severe. In generally considered to result from spasm of the main ar- the mild type, also called the localized type, there was de- ~ts of teries of the forearm, and their branches as a consequence generation of part of the flexor digitorum profundus mus- Acta of trauma to the elbow or forearm. The severe and pro- cle, causing contractures in only two or three fingers. longed but incomplete interruption of arterial blood sup- There were hardly any neurological signs, and when pres- ~. (in ply, together with venostasis, produces acute ischemic ent they were minimum. In the moderate type, the muscle z and necrosis of the flexor muscles. The most marked ischemia degeneration involved all or nearly all of the flexor digito- occurs in the deeply situated muscles such as the flexor rum profundus and flexor pollicis longus, with partial pollicis longus and flexor digitorum profundus, but severe degeneration of the superficial muscles as well. The neu- ischemia is evident in the pronator teres and flexor rological signs were invariably present and generally -484, digitorum superficialis muscles, and comparatively mild the median nerve was more severely affected than the :rtag, ischemia occurs in the superficially located muscles such ulnar nerve. In the severe type, there was degeneration as the wrist flexors. The muscle degeneration which fol- of all the flexor muscles with necrosis in the center ). -

FAT EMBOLISM SYNDROME WITHOUT OBJECTIVE EVIDENCE of BONE OR SOFT TISSUE INJURY Amitabh Das Shukla1, Rajneesh Kumar Srivastava2, Neha Agrawal3, Ravindra Kumar Singh4

DOI: 10.14260/jemds/2014/3611 CASE REPORT FAT EMBOLISM SYNDROME WITHOUT OBJECTIVE EVIDENCE OF BONE OR SOFT TISSUE INJURY Amitabh Das Shukla1, Rajneesh Kumar Srivastava2, Neha Agrawal3, Ravindra Kumar Singh4 HOW TO CITE THIS ARTICLE: Amitabh Das Shukla, Rajneesh Kumar Srivastava, Neha Agrawal, Ravindra Kumar Singh. “Fat Embolism Syndrome without Objective Evidence of Bone or Soft Tissue Injury”. Journal of Evolution of Medical and Dental Sciences 2014; Vol. 3, Issue 52, October 13; Page: 12209-12213, DOI: 10.14260/jemds/2014/3611 ABSTRACT: Fat embolism syndrome (FES), without evidence of bone or soft tissue injury is uncommon, and in absence of validated diagnostic criteria, its diagnosis is mainly dependent on treating clinician, who should have high index of suspicion. Treatment is predominantly supportive, and apart from some mortality, recovery is generally seen. Present article is a case report of a boy who suffered blunt injury due to fall from height, had no objective evidence of bone or soft tissue injury, but diagnosed as a case of fat embolism syndrome, using Gurd-Wilson and Schonfeld’s criteria, treated by pulmonary support and aggressive resuscitation, but he died after 4 days of admission to hospital. KEYWORDS: Fat Embolism, Bone injury, soft tissue injury. INTRODUCTION: Fat embolism syndrome after blunt trauma has significant morbidity and mortality. It poses a significant management problem, in patients with trauma. Generally it is secondary to fracture of femur or pelvis, which dislodges marrow fat, and results in fat embolism syndrome (FES). Fracture to long bones leads to fat embolism syndrome in 0.9 to 2.2% cases.1 In lung it presents with consolidation and diffusion defect, leading to symptom of respiratory distress and hypoxemia along with radiological picture of multiple consolidation, ground glass appearance and nodularity of lung.2 Its central nervous system manifestations include confusion, drowsiness and altered sensorium.3 Some patients also present with hemiparesis and partial siezures4. -

The Branching and Innervation Pattern of the Radial Nerve in the Forearm: Clarifying the Literature and Understanding Variations and Their Clinical Implications

diagnostics Article The Branching and Innervation Pattern of the Radial Nerve in the Forearm: Clarifying the Literature and Understanding Variations and Their Clinical Implications F. Kip Sawyer 1,2,* , Joshua J. Stefanik 3 and Rebecca S. Lufler 1 1 Department of Medical Education, Tufts University School of Medicine, Boston, MA 02111, USA; rebecca.lufl[email protected] 2 Department of Anesthesiology, Stanford University School of Medicine, Stanford, CA 94305, USA 3 Department of Physical Therapy, Movement and Rehabilitation Science, Bouve College of Health Sciences, Northeastern University, Boston, MA 02115, USA; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected] Received: 20 May 2020; Accepted: 29 May 2020; Published: 2 June 2020 Abstract: Background: This study attempted to clarify the innervation pattern of the muscles of the distal arm and posterior forearm through cadaveric dissection. Methods: Thirty-five cadavers were dissected to expose the radial nerve in the forearm. Each muscular branch of the nerve was identified and their length and distance along the nerve were recorded. These values were used to determine the typical branching and motor entry orders. Results: The typical branching order was brachialis, brachioradialis, extensor carpi radialis longus, extensor carpi radialis brevis, supinator, extensor digitorum, extensor carpi ulnaris, abductor pollicis longus, extensor digiti minimi, extensor pollicis brevis, extensor pollicis longus and extensor indicis. Notably, the radial nerve often innervated brachialis (60%), and its superficial branch often innervated extensor carpi radialis brevis (25.7%). Conclusions: The radial nerve exhibits significant variability in the posterior forearm. However, there is enough consistency to identify an archetypal pattern and order of innervation. These findings may also need to be considered when planning surgical approaches to the distal arm, elbow and proximal forearm to prevent an undue loss of motor function. -

Neurology of the Upper Limb

Neurology of the Upper limb Donald Sammut Hand Surgeon Kings Upper Limb Anatomy plus lecture notes The$Neck$ The$Nerve$roots$which$supply$the$Upper$Limb$are$C5$to$T1$ Pre<fixed$(C4$to$C8)$and$Post<fixed$(C6$to$T2)$plexus$not$uncommon.$ Also$common$contributions$from$C4$and$from$T2$in$a$normally$rooted$plexus.$ $ The$anterior$nerve$roots$emerge$between$the$vertebrae$and$immediately$pass$ $through$the$first$area$of$possible$compression:$ The$root$nerve$canal$is$bounded$$ Anteriorly$by$the$posterior$margin$of$the$intervertebral$disc$and$$ Posteriorly,$by$the$facet$joint$between$vertebrae.$ $ Pathology$of$the$disc,$or$joint,$or$both,$can$narrow$this$channel$and$compress$ $the$nerve$root$ The$roots$emerge$from$the$cervical$spine$into$the$plane$between$$ Scalenius$Anterior$and$Scalenius$Medius.$$ $ Scalenius*Anterior:** Origin:$Anterior$tubercles$of$Cervical$vertebae$C3$to$6$(C6$tubercle$is$the$Carotid$tubercle)$ Insertion:$The$scalene$tubercle$on$inner$border/upper$surface$1st$rib$ $ Scalenius*Medius:* Origin:$Posterior$tubercles$of$all$cervical$vertebrae$ Insertion:$Quadrangular$area$between$the$neck$and$subclavian$groove$1st$rib$ $ Exiting$from$the$Scalenes,$the$trunks$lie$in$the$posterior$triangle$of$the$neck.$ The$posterior$triangle$is$bounded$anteriorly$by$SternoCleidoMastoid$and$$ posteriorly$by$the$Trapezius.$ The$inferior$border$is$the$clavicle$.$ The$apex$of$the$triangle$superiorly$is$at$the$back$of$the$skull$on$the$superior$nuchal$line$ $ $ The$Posterior$Triangle$ SternoCleidoMastoid$ Trapezius$ Scalenius$Medius$ Scalenius$Anterior$ -

Case Report Forearm Compartment Syndrome Following Thrombolytic Therapy for Massive Pulmonary Embolism: a Case Report and Review of Literature

Hindawi Publishing Corporation Case Reports in Orthopedics Volume 2011, Article ID 678525, 4 pages doi:10.1155/2011/678525 Case Report Forearm Compartment Syndrome following Thrombolytic Therapy for Massive Pulmonary Embolism: A Case Report and Review of Literature Ravi Badge and Mukesh Hemmady Department of Trauma and Orthopaedics Surgery, Wrightington, Wigan and Leigh NHS Trust, Wigan WN1 2NN, UK Correspondence should be addressed to Ravi Badge, [email protected] Received 2 November 2011; Accepted 6 December 2011 Academic Editor: M. K. Lyons Copyright © 2011 R. Badge and M. Hemmady. This is an open access article distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited. Use of thrombolytic therapy in pulmonary embolism is restricted in cases of massive embolism. It achieves faster lysis of the thrombus than the conventional heparin therapy thus reducing the morbidity and mortality associated with PE. The compartment syndrome is a well-documented, potentially lethal complication of thrombolytic therapy and known to occur in the limbs involved for vascular lines or venepunctures. The compartment syndrome in a conscious and well-oriented patient is mainly diagnosed on clinical ground with its classical signs and symptoms like disproportionate pain, tense swollen limb and pain on passive stretch. However these findings may not be appropriately assessed in an unconscious patient and therefore the clinicians should have high index of suspicion in a patient with an acutely swollen tense limb. In such scenarios a prompt orthopaedic opinion should be considered. In this report, we present a case of acute compartment syndrome of the right forearm in a 78 years old male patient following repeated attempts to secure an arterial line for initiating the thrombolytic therapy for the management of massive pulmonary embolism. -

Gunshot Wounds of the Lower Extremity

The Northern Ohio Foot and Ankle Journal Official Publication of the NOFA Foundation Gunshot Wounds in the Lower Extremity by Michael Coyer DPM1, James Connors DPM1, and Mark Hardy DPM FACFAS2 The Northern Ohio Foot and Ankle Journal 1 (3): 1 Abstract: A high number of gunshot injuries occur in the lower extremities, making it likely that the foot and ankle surgeon will encounter these wounds if involved with lower extremity trauma care. An understanding of current thought processes and standards of care in relationship to high and low velocity wounds is imperative for the surgeon to appropriately manage these unique and challenging traumatic injuries. Also important are the legal considerations relating to evidence collection, interaction with law enforcement, and witness testimony. It is the intent of this article to provide the foot and ankle surgeon with standardized guidelines for the treatment of gunshot trauma in the lower extremities, as well as guidelines for appropriate documentation and evidence handling. Key words: Gunshot Wounds, Foot & Ankle Trauma, Gunshot Evidence, Lower Extremity Gunshots Accepted: March 2015 Published: March 2015 This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License. It permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited. ©The Northern Ohio Foot and Ankle Foundation Journal. (www.nofafoundation.org) 2015. All rights reserved. Introduction With more than 65 million handguns in the United States essential to provide effective care. Also important are the alone, the potential for encountering gunshot wounds is legal considerations relating to evidence collection, fairly high. -

Orthopedic Trauma Postoperative Care and Rehab

Orthopedic Trauma Postoperative Care and Rehab Serge Charles Kaska, MD Name that Beach 100$ Still 100$ 75$ 50$ 1$ Omaha • June 6th 1941 • !st Infantry Division • 2000 KIA LIFE OR LIMB THREAT 1. Compartment Syndrome 2. Fat Emboli Syndrome 3. Pulmonary Embolism 4. Shock Compartment syndrome case A 16 year old male was retrieving a tire from his truck bed on the side of the highway in the pouring rain when a car careens off of the road and sandwiches the patients legs between the bumpers at freeway speed. Acute compartment syndrome Compartment syndrome DEFINED Definition: Elevated tissue pressure within a closed fascial space • Pathogenesis – Too much in-flow: results in edema or hemorrhage – Decreased outflow: results in venous obstruction caused by tight dressing and/or cast. • Reduces tissue perfusion • Results in cell death Compartment syndrome tissue survival • Muscle – 3-4 hours: reversible changes – 6 hours: variable damage – 8 hours: irreversible changes • Nerve – 2 hours: looses nerve conduction – 4 hours: neuropraxia – 8 hours: irreversible changes Physical exam 1. Pain 2. Pain 3. Pain Physical exam • Inspection – Swelling, skin is tight and shiny • Motion – Active motion will be refused or unable. Must see dorsiflexion • Palpation – Severe pain with palpation • Alarming pain with passive stretch Physical exam • Dorsiflexion Physical Exam • Palpation – Severe pain with palpation • Alarming pain with passive stretch Physical exam • Evaluations from nurses, therapists, and orthotech’s are CRITICAL • If you call a doctor and say that -

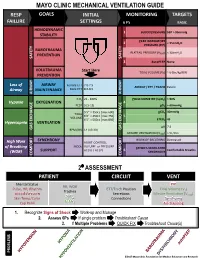

Mechanical Ventilation Guide

MAYO CLINIC MECHANICAL VENTILATION GUIDE RESP GOALS INITIAL MONITORING TARGETS FAILURE SETTINGS 6 P’s BASIC HEMODYNAMIC 1 BLOOD PRESSURE SBP > 90mmHg STABILITY PEAK INSPIRATORY 2 < 35cmH O PRESSURE (PIP) 2 BAROTRAUMA PLATEAU PRESSURE (P ) < 30cmH O PREVENTION PLAT 2 SAFETY SAFETY 3 AutoPEEP None VOLUTRAUMA Start Here TIDAL VOLUME (V ) ~ 6-8cc/kg IBW PREVENTION T Loss of AIRWAY Female ETT 7.0-7.5 AIRWAY / ETT / TRACH Patent Airway MAINTENANCE Male ETT 8.0-8.5 AIRWAY AIRWAY FiO2 21 - 100% PULSE OXIMETRY (SpO2) > 90% Hypoxia OXYGENATION 4 PEEP 5 [5-15] pO2 > 60mmHg 5’5” = 350cc [max 600] pCO2 40mmHg TIDAL 6’0” = 450cc [max 750] 5 VOLUME 6’5” = 500cc [max 850] ETCO2 45 Hypercapnia VENTILATION pH 7.4 GAS GAS EXCHANGE BPM (RR) 14 [10-30] GAS EXCHANGE MINUTE VENTILATION (VMIN) > 5L/min SYNCHRONY WORK OF BREATHING Decreased High Work ASSIST CONTROL MODE VOLUME or PRESSURE of Breathing PATIENT-VENTILATOR AC (V) / AC (P) 6 Comfortable Breaths (WOB) SUPPORT SYNCHRONY COMFORT COMFORT 2⁰ ASSESSMENT PATIENT CIRCUIT VENT Mental Status PIP RR, WOB Pulse, HR, Rhythm ETT/Trach Position Tidal Volume (V ) Trachea T Blood Pressure Secretions Minute Ventilation (V ) SpO MIN Skin Temp/Color 2 Connections Synchrony ETCO Cap Refill 2 Air-Trapping 1. Recognize Signs of Shock Work-up and Manage 2. Assess 6Ps If single problem Troubleshoot Cause 3. If Multiple Problems QUICK FIX Troubleshoot Cause(s) PROBLEMS ©2017 Mayo Clinic Foundation for Medical Education and Research CAUSES QUICK FIX MANAGEMENT Bleeding Hemostasis, Transfuse, Treat cause, Temperature control HYPOVOLEMIA Dehydration Fluid Resuscitation (End points = hypoxia, ↑StO2, ↓PVI) 3rd Spacing Treat cause, Beware of hypoxia (3rd spacing in lungs) Pneumothorax Needle D, Chest tube Abdominal Compartment Syndrome FLUID Treat Cause, Paralyze, Surgery (Open Abdomen) OBSTRUCTED BLOOD RETURN Air-Trapping (AutoPEEP) (if not hypoxic) Pop off vent & SEE SEPARATE CHART PEEP Reduce PEEP Cardiac Tamponade Pericardiocentesis, Drain. -

Acute Compartment Syndrome Complicating Deep Venous Thrombosis

SMGr up Case Report SM Journal of Acute Compartment Syndrome Case Reports Complicating Deep Venous Thrombosis Senthil Dhayalan1*, David Jardine1*, Tony Goh2 and Nicholas Lash3 1Senior registrar and General Physician, Dept of General Medicine, NZ 2Consultant Radiologist, Dept of Radiology, NZ 3Orthopaediac Surgeon, Dept of Orthopaedics, NZ A 40-yr old, heavily-built man initially presented to his general practitioner 2 days before Article Information admission with recent onset of pain and swelling in his left calf. A duplex ultrasound scan Received date: Nov 21, 2018 demonstrated a popliteal and lower leg deep vein thrombosis [DVT], extending 15 cm above the Accepted date: Nov 26, 2018 knee into the femoral vein. He was started appropriately on enoxaparin 130 mg bd. Despite the Published date: Nov 27, 2018 treatment, the pain got worse, particularly when standing, and he was admitted for symptom control. Five weeks earlier he had undergone anterior cruciate ligament repair of the left knee, *Corresponding author [without heparin prophylaxis] and made a satisfactory recovery (Figure 1). Jardine D, General Medicine On examination he was mildly distressed with a low-normal blood pressure [110/70 mmHg] Department, Christchurch hospital, and a persistent low-grade fever [temperature ranged from 37.0-37.8 oC]. The left leg was moderately Private Bag 4710, Christchurch 8140, diffusely swollen, slightly warm and darker in colour [figure]. The pain was localised to the posterior New Zealand, compartments and was exacerbated by dorsi-flexing the ankle and squeezing the gastrocnemius. Email: [email protected] There were no signs of joint effusion, thrombophlebitis, lymphadenopathy or cellulitis.