Reforming the Lords: the Role of the Bishops

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Short History of the Western Rite Vicariate

A Short History of the Western Rite Vicariate Benjamin Joseph Andersen, B.Phil, M.Div. HE Western Rite Vicariate of the Antiochian Orthodox Christian Archdiocese of North America was founded in 1958 by Metropolitan Antony Bashir (1896–1966) with the Right Reverend Alex- T ander Turner (1906–1971), and the Very Reverend Paul W. S. Schneirla. The Western Rite Vicariate (WRV) oversees parishes and missions within the Archdiocese that worship according to traditional West- ern Christian liturgical forms, derived either from the Latin-speaking Churches of the first millenium, or from certain later (post-schismatic) usages which are not contrary to the Orthodox Faith. The purpose of the WRV, as originally conceived in 1958, is threefold. First, the WRV serves an ecumeni- cal purpose. The ideal of true ecumenism, according to an Orthodox understanding, promotes “all efforts for the reunion of Christendom, without departing from the ancient foundation of our One Orthodox Church.”1 Second, the WRV serves a missionary and evangelistic purpose. There are a great many non-Orthodox Christians who are “attracted by our Orthodox Faith, but could not find a congenial home in the spiritual world of Eastern Christendom.”2 Third, the WRV exists to be witness to Orthodox Christians themselves to the universality of the Or- thodox Catholic Faith – a Faith which is not narrowly Byzantine, Hellenistic, or Slavic (as is sometimes assumed by non-Orthodox and Orthodox alike) but is the fulness of the Gospel of Jesus Christ for all men, in all places, at all times. In the words of Father Paul Schneirla, “the Western Rite restores the nor- mal cultural balance in the Church. -

Worldwide Communion: Episcopal and Anglican Lesson # 23 of 27

Worldwide Communion: Episcopal and Anglican Lesson # 23 of 27 Scripture/Memory Verse [Be] eager to maintain the unity of the Spirit in the bond of peace: There is one body and one Spirit just as you were called to the one hope that belongs to your call; one Lord, one Faith, one baptism, one God and Father of us all. Ephesians 4: 3 – 6 Lesson Goals & Objectives Goal: The students will gain an understanding and appreciation for the fact that we belong to a church that is larger than our own parish: we are part of The Episcopal Church (in America) which is also part of the worldwide Anglican Communion. Objectives: The students will become familiar with the meanings of the terms, Episcopal, Anglican, Communion (as referring to the larger church), ethos, standing committee, presiding bishop and general convention. The students will understand the meaning of the “Four Instruments of Unity:” The Archbishop of Canterbury; the Meeting of Primates; the Lambeth Conference of Bishops; and, the Anglican Consultative Council. The students will encounter the various levels of structure and governance in which we live as Episcopalians and Anglicans. The students will learn of and appreciate an outline of our history in the context of Anglicanism. The students will see themselves as part of a worldwide communion of fellowship and mission as Christians together with others from throughout the globe. The students will read and discuss the “Chicago-Lambeth Quadrilateral” (BCP pages 876 – 877) in order to appreciate the essentials of an Anglican identity. Introduction & Teacher Background This lesson can be as exciting to the students as you are willing to make it. -

Lords Reform White Paper and Draft Bill

GS Misc 1004 GENERAL SYNOD House of Lords Reform A Submission from the Archbishops of Canterbury and York to the Parliamentary Joint Committee on the Government’s Draft Bill and White Paper. General principles 1. More than a decade ago, the then Archbishops‟ submission to the Royal Commission on House of Lords Reform said that the test of reform was whether it would enable Parliament as a whole to serve the people better. That has remained the consistent position of Church of England submissions since. 2. As with any constitutional change, it is important, therefore, that there is clarity over the problems that reform is intended to address and a reasonable measure of assurance that the proposed solutions will work and avoid unintended consequences. Fundamental changes to how we are governed should also command a wide measure of consent within the country as well as in Parliament. 3. In his initial response of May 2011 to the White Paper and Draft Bill the Lords Spiritual Convenor, the Bishop of Leicester, said: “Some reform of the Lords is overdue, not least to resolve the problem of its ever-increasing membership. But getting the balance of reform right, so that we retain what is good in our current arrangements, whilst freeing up the House to operate more effectively and efficiently, is crucial.”1 In particular, the proposal to reduce the overall size of the House is welcome. But it is far less clear that wholesale reform of the House of Lords along the lines now envisaged gets the balance right. 4. For so long as the majority of the House of Lords consisted of the hereditary peerage there was manifestly a compelling case for reform. -

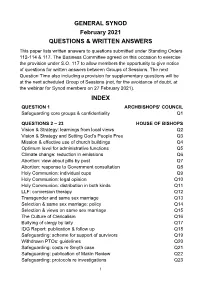

GENERAL SYNOD February 2021 QUESTIONS & WRITTEN ANSWERS

GENERAL SYNOD February 2021 QUESTIONS & WRITTEN ANSWERS This paper lists written answers to questions submitted under Standing Orders 112-114 & 117. The Business Committee agreed on this occasion to exercise the provision under S.O. 117 to allow members the opportunity to give notice of questions for written answers between Groups of Sessions. The next Question Time also including a provision for supplementary questions will be at the next scheduled Group of Sessions (not, for the avoidance of doubt, at the webinar for Synod members on 27 February 2021). INDEX QUESTION 1 ARCHBISHOPS’ COUNCIL Safeguarding core groups & confidentiality Q1 QUESTIONS 2 – 23 HOUSE OF BISHOPS Vision & Strategy: learnings from local views Q2 Vision & Strategy and Setting God’s People Free Q3 Mission & effective use of church buildings Q4 Optimum level for administrative functions Q5 Climate change: reduction in emissions Q6 Abortion: view about pills by post Q7 Abortion: response to Government consultation Q8 Holy Communion: individual cups Q9 Holy Communion: legal opinion Q10 Holy Communion: distribution in both kinds Q11 LLF: conversion therapy Q12 Transgender and same sex marriage Q13 Selection & same sex marriage: policy Q14 Selection & views on same sex marriage Q15 The Culture of Clericalism Q16 Bullying of clergy by laity Q17 IDG Report: publication & follow up Q18 Safeguarding: scheme for support of survivors Q19 Withdrawn PTOs: guidelines Q20 Safeguarding: costs re Smyth case Q21 Safeguarding: publication of Makin Review Q22 Safeguarding: protocols -

The Sovereignty of the Crown Dependencies and the British Overseas Territories in the Brexit Era

Island Studies Journal, 15(1), 2020, 151-168 The sovereignty of the Crown Dependencies and the British Overseas Territories in the Brexit era Maria Mut Bosque School of Law, Universitat Internacional de Catalunya, Spain MINECO DER 2017-86138, Ministry of Economic Affairs & Digital Transformation, Spain Institute of Commonwealth Studies, University of London, UK [email protected] (corresponding author) Abstract: This paper focuses on an analysis of the sovereignty of two territorial entities that have unique relations with the United Kingdom: the Crown Dependencies and the British Overseas Territories (BOTs). Each of these entities includes very different territories, with different legal statuses and varying forms of self-administration and constitutional linkages with the UK. However, they also share similarities and challenges that enable an analysis of these territories as a complete set. The incomplete sovereignty of the Crown Dependencies and BOTs has entailed that all these territories (except Gibraltar) have not been allowed to participate in the 2016 Brexit referendum or in the withdrawal negotiations with the EU. Moreover, it is reasonable to assume that Brexit is not an exceptional situation. In the future there will be more and more relevant international issues for these territories which will remain outside of their direct control, but will have a direct impact on them. Thus, if no adjustments are made to their statuses, these territories will have to keep trusting that the UK will be able to represent their interests at the same level as its own interests. Keywords: Brexit, British Overseas Territories (BOTs), constitutional status, Crown Dependencies, sovereignty https://doi.org/10.24043/isj.114 • Received June 2019, accepted March 2020 © 2020—Institute of Island Studies, University of Prince Edward Island, Canada. -

House of Keys General Election 2021 Guidance on Election Funding

Guidance on Election Funding House of Keys General Election 2021 Contents PART 1 INTRODUCTION ................................................................................................................................ 2 1.1 Purpose ......................................................................................................................................... 2 1.2 Resources ..................................................................................................................................... 2 1.3 Summary of requirements and restrictions ................................................................................. 2 PART 2 EXPENSES AND DONATIONS ............................................................................................................ 4 2.1 The limit on the amount of expenditure ...................................................................................... 4 2.2 To whom do the requirements apply? ......................................................................................... 4 2.3 What is the time period for the requirements? ........................................................................... 4 2.4 What is meant by “election expenses”? ...................................................................................... 4 2.5 What happens if someone else incurs expenses on your behalf? ............................................... 5 2.6 How are expenses incurred jointly by more than one candidate counted? ................................ 5 2.7 What happens if -

The Bank Restriction Act and the Regime Shift to Paper Money, 1797-1821

European Historical Economics Society EHES WORKING PAPERS IN ECONOMIC HISTORY | NO. 100 Danger to the Old Lady of Threadneedle Street? The Bank Restriction Act and the regime shift to paper money, 1797-1821 Patrick K. O’Brien Department of Economic History, London School of Economics Nuno Palma Department of History and Civilization, European University Institute Department of Economics, Econometrics, and Finance, University of Groningen JULY 2016 EHES Working Paper | No. 100 | July 2016 Danger to the Old Lady of Threadneedle Street? The Bank Restriction Act and the regime shift to paper money, 1797-1821* Patrick K. O’Brien Department of Economic History, London School of Economics Nuno Palma Department of History and Civilization, European University Institute Department of Economics, Econometrics, and Finance, University of Groningen Abstract The Bank Restriction Act of 1797 suspended the convertibility of the Bank of England's notes into gold. The current historical consensus is that the suspension was a result of the state's need to finance the war, France’s remonetization, a loss of confidence in the English country banks, and a run on the Bank of England’s reserves following a landing of French troops in Wales. We argue that while these factors help us understand the timing of the Restriction period, they cannot explain its success. We deploy new long-term data which leads us to a complementary explanation: the policy succeeded thanks to the reputation of the Bank of England, achieved through a century of prudential collaboration between the Bank and the Treasury. JEL classification: N13, N23, N43 Keywords: Bank of England, financial revolution, fiat money, money supply, monetary policy commitment, reputation, and time-consistency, regime shift, financial sector growth * We are grateful to Mark Dincecco, Rui Esteves, Alex Green, Marjolein 't Hart, Phillip Hoffman, Alejandra Irigoin, Richard Kleer, Kevin O’Rourke, Jaime Reis, Rebecca Simson, Albrecht Ritschl, Joan R. -

The Cathedral Church of St Peter in Exeter

The Cathedral Church of St Peter in Exeter Financial statements For the year ended 31 December 2019 Exeter Cathedral Contents Page Annual report 1 – 13 Statement of the Responsibilities of the Chapter 14 Independent auditors’ report 15-16 Consolidated statement of financial activities 17 Consolidated balance sheet 18 Cathedral balance sheet 19 Consolidated cash flow statement 20 Notes 21 – 41 Exeter Cathedral Annual Report For the year ended 31 December 2019 REFERENCE AND ADMINISTRATIVE INFORMATION Governing statute The Cathedral’s Constitution and Statutes were implemented on 24 November 2001 under the Cathedrals’ Measure 1999, and amended on 18 May 2007, 12 March 2014 and 14 January 2016, under the provisions of the Measure. The Chapter The administrative body is the Chapter. The members of the Chapter during the period 1 January 2019 to the date of approval of the annual report and financial statements were as follows: The Very Reverend Jonathan Greener Dean The Reverend Canon Dr Mike Williams Canon Treasurer The Reverend Canon Becky Totterdell Residentiary Canon (until October 2019) The Reverend Canon James Mustard Canon Precentor The Reverend Canon Dr Chris Palmer Canon Chancellor John Endacott FCA Chapter Canon The Venerable Dr Trevor Jones Chapter Canon Jenny Ellis CB Chapter Canon The Reverend Canon Cate Edmond Canon Steward (from October 2019) Address Cathedral Office 1 The Cloisters EXETER, EX1 1HS Staff with Management Responsibilities Administrator Catherine Escott Clerk of Works Christopher Sampson Director of Music Timothy -

British Overseas Territories Law

British Overseas Territories Law Second Edition Ian Hendry and Susan Dickson HART PUBLISHING Bloomsbury Publishing Plc Kemp House , Chawley Park, Cumnor Hill, Oxford , OX2 9PH , UK HART PUBLISHING, the Hart/Stag logo, BLOOMSBURY and the Diana logo are trademarks of Bloomsbury Publishing Plc First published in Great Britain 2018 First edition published in 2011 Copyright © Ian Hendry and Susan Dickson , 2018 Ian Hendry and Susan Dickson have asserted their right under the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988 to be identifi ed as Authors of this work. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or any information storage or retrieval system, without prior permission in writing from the publishers. While every care has been taken to ensure the accuracy of this work, no responsibility for loss or damage occasioned to any person acting or refraining from action as a result of any statement in it can be accepted by the authors, editors or publishers. All UK Government legislation and other public sector information used in the work is Crown Copyright © . All House of Lords and House of Commons information used in the work is Parliamentary Copyright © . This information is reused under the terms of the Open Government Licence v3.0 ( http://www.nationalarchives.gov.uk/doc/ open-government-licence/version/3 ) except where otherwise stated. All Eur-lex material used in the work is © European Union, http://eur-lex.europa.eu/ , 1998–2018. A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library. -

Catholicism and the Judiciary in Ireland, 1922-1960

IRISH JUDICIAL STUDIES JOURNAL 1 CATHOLICISM AND THE JUDICIARY IN IRELAND, 1922-1960 Abstract: This article examines evidence of judicial deference to Catholic norms during the period 1922-1960 based on a textual examination of court decisions and archival evidence of contact between Catholic clerics and judges. This article also examines legal judgments in the broader historical context of Church-State studies and, argues, that the continuity of the old orthodox system of law would not be easily superseded by a legal structure which reflected the growing pervasiveness of Catholic social teaching on politics and society. Author: Dr. Macdara Ó Drisceoil, BA, LLB, Ph.D, Barrister-at-Law Introduction The second edition of John Kelly’s The Irish Constitution was published with Sir John Lavery’s painting, The Blessing of the Colours1 on the cover. The painting is set in a Church and depicts a member of the Irish Free State army kneeling on one knee with his back arched over as he kneels down facing the ground. He is deep in prayer, while he clutches a tricolour the tips of which fall to the floor. The dominant figure in the painting is a Bishop standing confidently above the solider with a crozier in his left hand and his right arm raised as he blesses the soldier and the flag. To the Bishop’s left, an altar boy holds a Bible aloft. The message is clear: the Irish nation kneels facing the Catholic Church in docile piety and devotion. The synthesis between loyalty to the State and loyalty to the Catholic Church are viewed as interchangeable in Lavery’s painting. -

Evensong 9 August 2018 5:15 P.M

OUR VISION: A world where people experience God’s love and are made whole. OUR MISSION: To share the love of Jesus through compassion, inclusivity, creativity and learning. Evensong 9 August 2018 5:15 p.m. Evensong Thursday in the Eleventh Week after Pentecost • 9 August 2018 • 5:15 pm Welcome to Grace Cathedral. Choral Evensong marks the end of the working day and prepares for the approaching night. The roots of this service come out of ancient monastic traditions of Christian prayer. In this form, it was created by Thomas Cranmer, Archbishop of Canterbury in the 16th century, as part of the simplification of services within the newly-reformed Church of England. The Episcopal Church, as part of the worldwide Anglican Communion, has inherited this pattern of evening prayer. In this service we are invited to reflect on the business of the past day, to pray for the world and for ourselves, and to commend all into God’s hands as words of Holy Scripture are said and sung. The beauty of the music is offered to help us set our lives in the light of eternity; the same light which dwelt among us in Jesus, and which now illuminates us by the Spirit. May this service be a blessing to you. Voluntary Canzonetta William Mathias The people stand as the procession enters. The Invitatory and Psalter Opening Sentence Said by the officiant. Preces John Rutter Officiant O Lord, open thou our lips. Choir And our mouth shall shew forth thy praise. O God, make speed to save us. -

Reflections on Representation and Reform in the House of Lords

Our House: Reflections on Representation and Reform in the House of Lords Edited by Caroline Julian About ResPublica ResPublica is an independent, non-partisan UK think tank founded by Phillip Blond in November 2009. In July 2011, the ResPublica Trust was established as a not-for-profit entity which oversees all of ResPublica’s domestic work. We focus on developing practical solutions to enduring socio-economic and cultural problems of our time, such as poverty, asset inequality, family and social breakdown, and environmental degradation. ResPublica Essay Collections ResPublica’s work draws together some of the most exciting thinkers in the UK and internationally to explore the new polices and approaches that will create and deliver a new political settlement. Our network of contributors who advise on and inform our work include leaders from politics, business, civil society and academia. Through our publications, compendiums and website we encourage other thinkers, politicians and members of the public to join the debate and contribute to the development of forward-thinking and innovative ideas. We intend our essay collections to stimulate balanced debate around issues that are fundamental to our core principles. Contents Foreword by Professor John Milbank and Professor Simon Lee, Trustees, 1 The ResPublica Trust 1. Introduction 4 Caroline Julian, ResPublica 2. A Statement from the Government 9 Mark Harper MP, Minister for Political and Constitutional Reform A Social Purpose 3. A Truly Representative House of Lords 13 The Rt Hon Frank Field, MP for Birkenhead 4. Association and Civic Participation 16 Dr Adrian Pabst, University of Kent 5. Bicameralism & Representative Democracy: An International Perspective 23 Rafal Heydel-Mankoo 6.