Houses of the Holy

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Arizona 500 2021 Final List of Songs

ARIZONA 500 2021 FINAL LIST OF SONGS # SONG ARTIST Run Time 1 SWEET EMOTION AEROSMITH 4:20 2 YOU SHOOK ME ALL NIGHT LONG AC/DC 3:28 3 BOHEMIAN RHAPSODY QUEEN 5:49 4 KASHMIR LED ZEPPELIN 8:23 5 I LOVE ROCK N' ROLL JOAN JETT AND THE BLACKHEARTS 2:52 6 HAVE YOU EVER SEEN THE RAIN? CREEDENCE CLEARWATER REVIVAL 2:34 7 THE HAPPIEST DAYS OF OUR LIVES/ANOTHER BRICK IN THE WALL PART TWO ANOTHER BRICK IN THE WALL PART TWO 5:35 8 WELCOME TO THE JUNGLE GUNS N' ROSES 4:23 9 ERUPTION/YOU REALLY GOT ME VAN HALEN 4:15 10 DREAMS FLEETWOOD MAC 4:10 11 CRAZY TRAIN OZZY OSBOURNE 4:42 12 MORE THAN A FEELING BOSTON 4:40 13 CARRY ON WAYWARD SON KANSAS 5:17 14 TAKE IT EASY EAGLES 3:25 15 PARANOID BLACK SABBATH 2:44 16 DON'T STOP BELIEVIN' JOURNEY 4:08 17 SWEET HOME ALABAMA LYNYRD SKYNYRD 4:38 18 STAIRWAY TO HEAVEN LED ZEPPELIN 7:58 19 ROCK YOU LIKE A HURRICANE SCORPIONS 4:09 20 WE WILL ROCK YOU/WE ARE THE CHAMPIONS QUEEN 4:58 21 IN THE AIR TONIGHT PHIL COLLINS 5:21 22 LIVE AND LET DIE PAUL MCCARTNEY AND WINGS 2:58 23 HIGHWAY TO HELL AC/DC 3:26 24 DREAM ON AEROSMITH 4:21 25 EDGE OF SEVENTEEN STEVIE NICKS 5:16 26 BLACK DOG LED ZEPPELIN 4:49 27 THE JOKER STEVE MILLER BAND 4:22 28 WHITE WEDDING BILLY IDOL 4:03 29 SYMPATHY FOR THE DEVIL ROLLING STONES 6:21 30 WALK THIS WAY AEROSMITH 3:34 31 HEARTBREAKER PAT BENATAR 3:25 32 COME TOGETHER BEATLES 4:06 33 BAD COMPANY BAD COMPANY 4:32 34 SWEET CHILD O' MINE GUNS N' ROSES 5:50 35 I WANT YOU TO WANT ME CHEAP TRICK 3:33 36 BARRACUDA HEART 4:20 37 COMFORTABLY NUMB PINK FLOYD 6:14 38 IMMIGRANT SONG LED ZEPPELIN 2:20 39 THE -

MOJO Led Zeppelin – Physical Graffiti Redrawn Special Edition Barnes & Nobles Stockist in North America

MOJO Led Zeppelin – Physical Graffiti Redrawn Special Edition Barnes & Nobles Stockist in North America Barnes & Noble #2675 33 East 17th St New York NY 10003 Barnes & Noble #2597 765 S Rt 17 Paramus NJ 07652 Barnes & Noble #2234 555 Fifth Avenue New York NY 10017 Barnes & Noble #2115 800 Boyleston St. Suite 179 Boston MA 02199 Barnes & Noble #2040 555 12th Street NW Washington DC 20004 Barnes & Noble #2850 1805 Walnut St. Philadelphia PA 19103 Barnes & Noble #2089 189 The Grove Drive t Suite K30 Los Angeles CA 90036 Barnes & Noble #2249 1450 Ala Moana Bl #1272 Honolulu HI 96814 Barnes & Noble #2216 91 Old Country Road Carle Place NY 11514 Barnes& Noble #2876 271 7th Avenue Brooklyn NY 11215 Barnes & Noble #2764 12089 Rockville Pike Rockville MD 20852 Barnes & Noble #2965 106 Court Street Brooklyn NY 11201 Barnes & Noble #2361 297 Oakbrook Center Oak Brook IL 60523 Barnes & Noble #2923 396 John R. Road Troy MI 48083 Barnes & Noble #2046 58 South 32nd Street Camp Hill PA 17011 Barnes & Noble #2275 131 Colonie Center #355 Albany NY 12205 Barnes & Noble #2790 3349 Monroe Avenue Rochester NY 14618 Barnes & Noble #2574 Country Club PlaZa 420 W. 47th Street Kansas City MO 64112 Barnes & Noble #2614 2100 N Snelling Ave Roseville MN 55113 Barnes & Noble #2964 160 Orland Park Place Orland IL 60462 Barnes & Noble #2107 3235 Washtenaw Ann Arbor MI 48104 Barnes & Noble #2645 Shopper's World 1 Worcester Rd Framingham MA 01701 Barnes & Noble #2648 17111 Haggerty Road Northville MI 48167 Barnes & Noble #2937 12193 Fair Lakes Promenad Fairfax VA 22033 Barnes & Noble #1979 83rd & Broadway 2289 Broadway New York NY 10024 Barnes & Noble #2902 4015 Medina Rd Akron OH 44333 Barnes & Noble #2776 Burlington II 102 Dorset Road South Burlington VT 05403 Barnes & Noble #2869 150 W. -

Led Zeppelin Iii & Iv

Guitar Lead LED ZEPPELIN III & IV Drums Bass (including solos) Guitar Rhythm Guitar 3 Keys Vocals Backup Vocals Percussion/Extra 1 IMMIGRANT SONG (SD) Aidan RJ Dahlia Ben & Isabelle Kelly Acoustic (main part with high Low acoustic 2 FRIENDS (ENC) (CGCGCE) Mack notes) - Giulietta chords - Turner Strings - Ian Eryn Congas - James Synth (riffy chords) - (strummy chords) - (transitions from 3 CELEBRATION DAY (ENC) James Mack Jimmy Turner Slide - Aspen Friends) - ??? Giulietta Eryn SINCE I'VE BEEN LOVING YOU (Both Rhythm guitar 4 schools) Jaden RJ under solo - ??? Organ - ??? Kelly 5 OUT ON THE TILES (SD) Ethan Ben Dahlia Ryan Kelly Acoustic (starts at Electric solo beginning) - Aspen, (starts at 3:30) - Acoustic (starts at 6 GALLOWS POLE (ENC) Jimmy Mack James 1:05) - Turner Mandolin - Ian Eryn Banjo - Giulietta Electric guitar (including solo Acoustic and wahwah Acoustic main - Rhythm - 7 TANGERINE (SD) (First chord is Am) Ethan Aidan parts) - Isabelle Ben Dahlia Kelly Ryan g Electric slide - Acoustic - Aspen, Mandolin - 8 THAT'S THE WAY (ENC) (DGDGBD) RJ Turner Acoustic #2 - Ian Jimmy Giulietta Eryn Tambo - James Claps - Jaden, Acoustic - Shaker -Ethan, 9 BRON-YR-AUR STOMP (SD) (CFCFAC) Aidan Jaden Dahlia Acoustic - Ben Ryan Kelly Castanets - Kelly HATS OF TO YOU (ROY) HARPER Acoustic slide - 10 (CGCEGC) ??? 11 BLACK DOG (ENC) Jimmy Mack Giulietta James Aspen Eryn Giulietta Piano (starts after solo) - 12 ROCK AND ROLL (SD) Ethan Aidan Dahlia Isabelle Rebecca Ryan Tambo - Aidan Acoustic - Mandolin - The Sandy Jimmy, Acoustic Giulietta, Mandolin -

Inside the Cages of the Zoo

The Library of America • Story of the Week From Shake It Up: Great American Writing on Rock and Pop from Elvis to Jay Z (Library of America, 2017), pages 151–65. Originally published in Trips: Rock Life in the Sixties (1973). Copyright © by Ellen Sander. ▼ Ellen Sander Ellen Sander (b. 1944) was The Saturday Review’s rock critic in the mid- to late sixties and also wrote on rock for Vogue, The Realist, Cavalier, The L.A. Free Press, the Sunday New York Times Arts & Leisure section, and many other venues. She is the author of Trips: Rock Life in the Sixties (1973), an important source for those seeking to understand the texture and allure of 1960s rock culture. A unique aspect of that culture was captured in Sander’s piece “The Case of the Cock- Sure Groupies” (1968), a remarkably clear- eyed and nonjudgmental account of one of rock’s less celebrated scenes. After her years of rock writing, Sander worked in various capacities in the software industry, from tech writing to computational linguistics. She then returned to her first love, poetry; most recently she served as the Poet Laure- ate of Belfast, Maine (2013–2014). Several collections of her rock journalism are available as Kindle ebooks. ▼ ▼ ▼ ▼ ▼ ▼ ▼ ▼ ▼ ▼ ▼ ▼ ▼ ▼ ▼ ▼ ▼ ▼ ▼ ▼ ▼ ▼ ▼ ▼ Inside the Cages of the Zoo Some years later, a group called Led Zeppelin came to America to make it, taking a highly calculated risk. The group had been put together around Jimmy Page, who had a heavy personal following from his previous work with the Yardbirds, an immensely popular British group that generated a great deal of charisma in the States. -

A Tribute to Led Zeppelin from Hell's Kitchen Liner Notes

Led Blimpie: A Tribute to Led Zeppelin from Hell’s Kitchen Liner Notes Originally begun as a 3 song demo, this project evolved into a full-on research project to discover the recording styles used to capture Zeppelin's original tracks. Sifting through over 3 decades of interviews, finding the gems where Page revealed his approach, the band enrolled in “Zeppelin University” and received their doctorate in “Jimmy Page's Recording Techniques”. The result is their thesis, an album entitled: A Tribute to Led Zeppelin from Hell's Kitchen. The physical CD and digipack are adorned with original Led Blimpie artwork that parodies the iconic Zeppelin imagery. "This was one of the most challenging projects I've ever had as a producer/engineer...think of it; to create an accurate reproduction of Jimmy Page's late 60's/early 70's analog productions using modern recording gear in my small project studio. Hats off to the boys in the band and to everyone involved.. Enjoy!" -Freddie Katz Co-Producer/Engineer Following is a track-by-track telling of how it all came together by Co-Producer and Led Blimpie guitarist, Thor Fields. Black Dog -originally from Led Zeppelin IV The guitar tone on this particular track has a very distinct sound. The left guitar was played live with the band through a Marshall JCM 800 half stack with 4X12's, while the right and middle (overdubbed) guitars went straight into the mic channel of the mixing board and then into two compressors in series. For the Leslie sounds on the solo, we used the Neo Instruments “Ventilator" in stereo (outputting to two amps). -

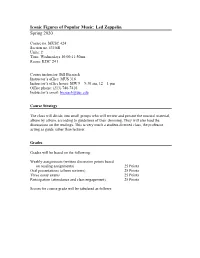

MUSC 424 Led Zeppelin Spring 20

Iconic Figures of Popular Music: Led Zeppelin Spring 2020 Course no. MUSC 424 Section no. 47256R Units: 2 Time: Wednesdays 10:00-11:50am Room: KDC 241 Course instructor: Bill Biersach Instructor’s office: MUS 316 Instructor’s office hours: MW 9 – 9:30 am, 12 – 1 pm Office phone: (213) 740-7416 Instructor’s email: [email protected] Course Strategy The class will divide into small groups who will review and present the musical material, album by album, according to guidelines of their choosing. They will also lead the discussions on the readings. This is very much a student-directed class, the professor acting as guide rather than lecturer. Grades Grades will be based on the following: Weekly assignments (written discussion points based on reading assignments) 25 Points Oral presentations (album reviews) 25 Points Three essay exams 25 Points Participation (attendance and class engagement) 25 Points Scores for course grade will be tabulated as follows: Texts Required (available in paperback or Kindle format): Cole, Richard Stairway to Heaven: Led Zeppelin Uncensored Dey St. (An Imprint of William Morrow Publishers), It Books; Reprint Edition, 2002 ISBN-13: 978-0060938376 Kindle: Harper Collins e-books; Reprint edition, 2009 ASIN: B000TG1X70 Davis, Stephen Hammer of the Gods: The Led Zeppelin Saga Dey St. (An Imprint of William Morrow Publishers), It Books; Reprint Edition, 2008 ISBN: 978-0-06-147308-1 pk. Led Zeppelin Spring 2020 Schedule of Discussion Topics and Reading Assignments WEEK ALBUM DATE Stephen Davis Richard Cole Hammer of Stairway to Heaven: the Gods Led Zep Uncensored 1. Preliminaries Jan. -

Download PDF > Articles on Led Zeppelin Albums, Including: Led

[PDF] Articles On Led Zeppelin Albums, including: Led Zeppelin (album), Led Zeppelin Ii, Led Zeppelin Iii,... Articles On Led Zeppelin Albums, including: Led Zeppelin (album), Led Zeppelin Ii, Led Zeppelin Iii, Led Zeppelin Iv, Houses Of The Holy, Physical Graffiti, Presence (album), In Through The Out Door Book Review It is an awesome ebook which i actually have at any time read through. It usually fails to charge excessive. It is extremely difficult to leave it before concluding, once you begin to read the book. (Dario Murazik IV ) A RTICLES ON LED ZEPPELIN A LBUMS, INCLUDING: LED ZEPPELIN (A LBUM), LED ZEPPELIN II, LED ZEPPELIN III, LED ZEPPELIN IV, HOUSES OF THE HOLY, PHYSICA L GRA FFITI, PRESENCE (A LBUM), IN THROUGH THE OUT DOOR - To save A rticles On Led Zeppelin A lbums, including : Led Zeppelin (album), Led Zeppelin Ii, Led Zeppelin Iii, Led Zeppelin Iv, Houses Of The Holy, Physical Graffiti, Presence (album), In Throug h The Out Door PDF, please click the button under and save the document or have accessibility to other information that are highly relevant to Articles On Led Zeppelin Albums, including: Led Zeppelin (album), Led Zeppelin Ii, Led Zeppelin Iii, Led Zeppelin Iv, Houses Of The Holy, Physical Graffiti, Presence (album), In Through The Out Door book. » Download A rticles On Led Zeppelin A lbums, including : Led Zeppelin (album), Led Zeppelin Ii, Led Zeppelin Iii, Led Zeppelin Iv, Houses Of The Holy, Physical Graffiti, Presence (album), In Throug h The Out Door PDF « Our web service was released having a wish to work as a comprehensive on the internet digital library that provides access to many PDF publication collection. -

Classic Rock/ Metal/ Blues

CLASSIC ROCK/ METAL/ BLUES Caught Up In You- .38 Special Girls Got Rhythm- AC/DC You Shook Me All Night Long- AC/DC Angel- Aerosmith Rag Doll- Aerosmith Walk This Way- Aerosmith What It Takes- Aerosmith Blue Sky- The Allman Brothers Band Melissa- The Allman Brothers Band Midnight Rider- The Allman Brothers Band One Way Out- The Allman Brothers Band Ramblin’ Man- The Allman Brothers Band Seven Turns- The Allman Brothers Band Soulshine- The Allman Brothers Band House Of The Rising Sun- The Animals Takin’ Care Of Business- Bachman-Turner Overdive You Ain’t Seen Nothing Yet- Bachman-Turner Overdrive Feel Like Makin’ Love- Bad Company Shooting Star- Bad Company Up On Cripple Creek- The Band The Weight- The Band All My Loving- The Beatles All You Need Is Love- The Beatles Blackbird- The Beatles Eight Days A Week- The Beatles A Hard Day’s Night- The Beatles Hello, Goodbye- The Beatles Here Comes The Sun- The Beatles Hey Jude- The Beatles In My Life- The Beatles I Will- Beatles Let It Be- The Beatles Norwegian Wood (This Bird Has Flown)- The Beatles Ob-La-Di, Ob-La-Da- The Beatles Oh! Darling- The Beatles Rocky Raccoon- The Beatles She Loves You- The Beatles Something- The Beatles CLASSIC ROCK/ METAL/ BLUES Ticket To Ride- The Beatles Tomorrow Never Knows- The Beatles We Can Work It Out- The Beatles When I’m Sixty-Four- The Beatles While My Guitar Gently Weeps- The Beatles With A Little Help From My Friends- The Beatles You’ve Got To Hide Your Love Away- The Beatles Johnny B. -

Achilles Last Stand 20/07/2010 10:18

LED ZEPPELIN :: ACHILLES LAST STAND 20/07/2010 10:18 Music and Las Vegas have always gone hand in hand, the best part about us online casinos No Zeppelin. Just LED. is you can listen to your own music while you play. LED Lighting Shop LUMERON Advertisement Advertisement Home News Multimedia Reference Interactive Contact Us Sitemap Deborah Bonham, A Family Act By Adam Vickery Deborah Bonham is the youngest child of John Sr. and Joan Bonham. Raised in Worcestershire, Deb found herself becoming fascinated with the idea of performing music. Her eldest brother John had joined Led Zeppelin when Deborah was just five years old. When Deb became a teenager, she would often sit and jam with her nephew Jason who was only a few years younger. They would write their own material and perform for family and friends. It’s with a little encouragement and with the John Bonham help of Robert Plant she was able to record a demo and have some success with her debut album For You and the Mick Bonham Moon. Best Price $14.87 or Buy New $18.21 Today, Deborah has achieved great success professionally. Deb has always been goal oriented and she has pushed forward no matter what the circumstances. It’s well known the tragedy of her brother John, who died back in September 1980 but, another grief-sickening moment came on January 14, 2000, when her brother Mick died suddenly of a heart attack. Mick was a good natured person, who in latter years chummed around with John listening to Motown music and getting into mischief about the town. -

Sensationelle Reihe Der Re-Issues Wird Fortgeführt! Led Zeppelin IV & Houses of the Holy Ab 24

im Auftrag: medienAgentur Stefan Michel T 040-5149 1467 F 040-5149 1465 [email protected] Sensationelle Reihe der Re-Issues wird fortgeführt! Led Zeppelin IV & Houses Of The Holy ab 24. Oktober erhältlich Produziert und Remastert von Jimmy Page Companion-Discs mit unveröffentlichten Aufnahmen Mehrere CD-, Vinyl-, und Digital-Formate sowie ein „Limited Edition Super Deluxe Box-Set“ Der Auftakt der großen LED ZEPPELIN-Wiederveröffentlichungsreihe im Juni war weltweit eine Sensation: In Deutschland katapultierten sich alle drei Re-Issues, Led Zeppelin, Led Zeppelin II und Led Zeppelin III, in die Top- 15 der Charts, in den USA erreichten sie die Top-20 der Billboard-Charts und ähnlich sah es in Kanada, Frankreich, Japan, England und weiteren Ländern aus. Im Oktober kommen die nächsten beiden Kultalben, die Jimmy Page wieder persönlich überarbeitet und zeitgemäß aufgefrischt hat: Das grandiose Led Zeppelin IV (das drittmeistverkaufte Album überhaupt in den USA) und das fantastische Houses Of The Holy! Wie die bisher erschienenen Re-Issues wurden auch Led Zeppelin IV und Houses Of The Holy von Gitarrist und Produzent Jimmy Page persönlich neu gemastert, der sich mit Leidenschaft und großem Können den originalen Analogbändern gewidmet hat. Zudem enthalten die Alben jeweils eine zweite CD mit bisher unveröffentlichten Mixen und Alternate Takes, die einen überraschenden Einblick in die Arbeit am jeweiligen Album präsentieren. Auch diesmal bedienen mehrere Konfigurationen jeden Wunsch der Fans: Led Zeppelin IV und Houses Of The Holy erscheinen am 24. Oktober über Atlantic/Swan Song in folgenden Formaten: Single CD – Remastertes Album im Klappcover. Deluxe Edition (2CD) – Remastertes Album mit zusätzlicher Companion Audio Disc. -

Led Zeppelin Houses of the Holy Full Album Zip

Led Zeppelin Houses Of The Holy Full Album Zip 1 / 4 Led Zeppelin Houses Of The Holy Full Album Zip 2 / 4 3 / 4 Download Led Zeppelin - Houses Of The Holy - 01 - The Song Remains The ... Download Led Zeppelin - Houses Of The Holy - 03 - Over The Hills And Far Away.. 1973. Another great album from one of the greatest artists of all time.. Elton John: Reg Strikes Back • Elton's 22nd gold album! ... Led Zeppelin: Houses Of The Holy (Atlantic) 153606. ... 3D HARD ROCK 4 D POP/SOFT ROCK 5 D CLASSICAL (PLEASE PRINT) Apt. City State Zip ! ... take up to one full year to do it.. Elton John: Reg Strikes Back • Elton's 22nd gold album! ... Led Zeppelin: Houses Of The Holy (Atlantic) 153606. ... Bonus Savings with every CD you buy at regular Club prices, effective with your first full-price purchase! ... City State Zip COMPACT | Telephone ( n Signature Limited to new members, continental USA only.. Led Zeppelin presentó elementos de un amplio espectro de ... 1973 House of the holy: ... 1999 Early days the best of led zeppelin, Vol I:. Elton John: Reg Strikes Back • Elton's 22nd gold album! ... Led Zeppelin: Houses Of The Holy (Atlantic) Guns ,1, 153606. ... Savings with every CD you buy at regular Club prices, effective with your first full-price purchase! ... ROCK 5 □ CLASSICAL (PLEASE PRINT) Apt. Zip Telephone ( A Signature YDTAD (BU) Limited to .... 100602. Elton John: Reg Strikes Back • Elton's 22nd gold album! (MCA) 2641 34. ... Led Zeppelin: Houses Of The Holy (Atlantic) 153606. INXS: Kick •Need You .... (2019) zip download Led Zeppelin - Led Zeppelin x Led Zeppelin (2019) album zip download. -

The Led Zeppelin Anthology : 1968-1980

audio-tape.ps, version 1.27, 1994 Jamie Zawinski <[email protected]> If you aren't printing this on the back of a used sheet of paper, you should be feeling very guilty about killing trees right now. Tape 1/8 Tape The Led Zeppelin Anthology : 1968-1980 : Anthology Zeppelin Led The elin pp ze Anthology - Tape 1/8 Tape - Anthology led SIDE 1/16 - LED ZEPPELIN SIDE 2/16 - LED ZEPPELIN II ^ 1 6:46 - Babe I'm Gonna Leave You (Take 8) = 1 3:07 - Sunshine Woman ^ 2 6:21 - Babe I'm Gonna Leave You (Take 9) - 2 0:24 - Moby Dick ^ 3 7:59 - You Shook Me (Take 1) ^ 3 8:49 - Moby Dick ^ 4 1:27 - Baby Come On Home (Instrumental - Take 1) " 4 3:01 - The Girl I Love ^ 5 1:26 - Baby Come On Home (Instrumental - Take 2) " 5 2:08 - Something Else ^ 6 0:14 - Baby Come On Home (Instrumental - Take 3) = 6 3:12 - Suga Mama ^ 7 5:30 - Baby Come On Home (Alternate Mix) & 7 16:47 - Jennings Farm Blues (Rehearsals) ^ 8 2:46 - Guitar/Organ Instrumental #1 & 8 6:24 - Jennings Farm Blues (Final Take) ^ 9 5:25 - Guitar/Organ Instrumental #2 -10 3:03 - Guitar/Organ Instrumental #3 43:52 - TOTAL 40:57 - TOTAL 1968-1969 SIDE 1/16 - LED ZEPPELIN SIDE 2/16 - LED ZEPPELIN II 1--7 - September 27, 1968 - Olympic Studios, London 1 - April 14, 1969 - BBC Maida Vale Studio, London 8-10 - October, 1968 - Olympic Studios, London 2--3 - May, 1969 - Mirror Studios, Los Angeles, California 4--5 - June 16, 1969 - Aeolian Hall, Bond St, London Master dubbed on May 30, 1997 6 - June/July, 1969 - Morgan Studios, London 7--8 - November, 1969 - Olympic Studios, London Master dubbed on May 30, 1997 Extra notes: track 2 fades, but includes longer count in audio-tape.ps, version 1.27, 1994 Jamie Zawinski <[email protected]> If you aren't printing this on the back of a used sheet of paper, you should be feeling very guilty about killing trees right now.