A Qualitative Exploration of Evangelical Christians' Perceptions

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Comparative-Qualitative Research Analysis of Character Education in the Christian School and Home Education Milieu Gretchen M

Cedarville University DigitalCommons@Cedarville Master of Education Research Theses Master of Education Capstones 5-2005 A Comparative-Qualitative Research Analysis of Character Education in the Christian School and Home Education Milieu Gretchen M. Wilhelm Cedarville University Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.cedarville.edu/education_theses Part of the Education Commons Recommended Citation Wilhelm, Gretchen M., "A Comparative-Qualitative Research Analysis of Character Education in the Christian School and Home Education Milieu" (2005). Master of Education Research Theses. 12. http://digitalcommons.cedarville.edu/education_theses/12 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by DigitalCommons@Cedarville, a service of the Centennial Library. It has been accepted for inclusion in Master of Education Research Theses by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@Cedarville. For more information, please contact [email protected]. A COMPARATIVE-QUALITATIVE RESEARCH ANALYSIS OF CHARACTER EDUCATION IN THE CHRISTIAN SCHOOL AND HOME EDUCATION MILIEU A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Masters of Education By GRETCHEN MARIE WILHELM B.M. Music History and Literature, Baldwin-Wallace Conservatory of Music, 2002 2005 Cedarville University ABSTRACT Wilhelm, Gretchen Marie. M. Ed. Education Dept., Cedarville University, 2005. A Comparative-Qualitative Research Analysis of Character Education in the Christian School and Home Education Milieu. This qualitative study provides a phenomenological perspective and comparative analysis of character education within the Christian school and home education milieu. The study is based on semi-structured interviews of fifty-two individuals (N = 52) representative of a sampling of Christian educators from four private, evangelical Christian Schools (n = 26) and area home educating families (n = 26). -

The Central Principle of Calvinism? Some Criteria, Proposals and Questions

Page 1 of 8 Original Research The central principle of Calvinism? Some criteria, proposals and questions Author: Is there a ‘central principle’ of Calvinism? This article explores this question mainly from the 1 Renato Coletto viewpoint of reformational philosophy. It does so firstly by introducing criteria that should Affiliation: be used to identify, if possible, such a central ‘organon’ of Calvinism. Then a few proposals are 1School of Philosophy, evaluated, and their strong and weak points are discussed. The most credible candidate for the North-West University, role of central principle is argued to be an ‘idea of law’ rooted in the biblical groundmotif and Potchefstroom Campus, traditionally defined as ‘sphere-sovereignty’. More recent characterisations of this cosmonomic South Africa idea are considered. A few objections and alternative proposals are also discussed. The article Correspondence to: is concluded with a few questions, calling for further research on the topic. Renato Coletto Email: [email protected] Wat is die sentrale beginsel van Calvinisme? Enkele kriteria, voorstelle en vrae. Is daar ’n ‘sentrale beginsel’ by Calvinisme te bespeur? Hierdie artikel ondersoek genoemde vraag Postal address: hoofsaaklik vanuit die perspektief van die reformatoriese filosofie. Dit word eerstens gedoen Private Bag X6001, Internal deur die kriteria bekend te stel wat gebruik moet word om, indien moontlik, sodanige Box 208, Potchefstroom 2520, South Africa ‘organologie’ van Calvinisme te identifiseer. ’n Paar voorstelle word dan geëvalueer en hulle sterk en swak punte bespreek. Die geloofwaardigste kandidaat vir die rol van ’n sentrale Dates: beginsel is moontlik ’n ‘wetsidee’ wat in die bybelse grondmotief gewortel is en tradisioneel Received: 14 Apr. -

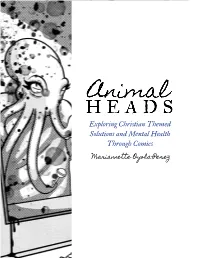

Exploring Christian Themed Solutions and Mental Health Through Comics

Exploring Christian Themed Solutions and Mental Health Through Comics Mariannette Oyola-Perez Exploring Christian Themed Solutions and Mental Health Through Comics Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of for the Degree of Master of Fine Arts at Liberty University Todd Smith, Chair Joshua Wilson, First Reader Paul Reynolds, Second Reader Todd Smith, Department Chair for me. Equiam, Zabdiel and Abigail, Dedication you guys are the reason I strive for This book is dedicated to anyone improvement. You are infinitely who refuses to accept that there will important, special, and wanted. Tio only ever be darkness. To the light- Juanra, you are the best example of seekers and the fighters: there is what the Lord can do when someone hope. You have a choice. is present and willing to learn. A huge thank you goes out Acknowledgements to my thesis friends, Sarah, Joy, This thesis could not have been Zach, and Andrea: without you completed without the help of my guys, panic moments would have loving family. Tio Roberto, you are been permanent panic. A huge, huge the one the Lord has placed in my thanks goes out to Charlie Benz for life to guide me through discipline writing Animal Head’s script and and love. Without your instruction, being my best friend throughout all there is no doubt whatsoever that this process. I wouldn’t be where I am today. Thanks to my wonderful Titi Madeline, your constant love professors, Monique Maloney, Paul and compassion is my example to Reynolds, Joshua Wilson and Todd follow. You are an example of loyalty Smith for your guidance, constant through thick and thin—one that I affirmation and sound instruction. -

Pedagogy for Christian Worldview Formation: a Grounded Theory Study of Bible College Teaching Methods Rob Lindemann George Fox University, [email protected]

Digital Commons @ George Fox University Doctor of Education (EdD) Theses and Dissertations 4-1-2016 Pedagogy For Christian Worldview Formation: A Grounded Theory Study of Bible College Teaching Methods Rob Lindemann George Fox University, [email protected] This research is a product of the Doctor of Education (EdD) program at George Fox University. Find out more about the program. Recommended Citation Lindemann, Rob, "Pedagogy For Christian Worldview Formation: A Grounded Theory Study of Bible College Teaching Methods" (2016). Doctor of Education (EdD). 71. https://digitalcommons.georgefox.edu/edd/71 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses and Dissertations at Digital Commons @ George Fox University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Doctor of Education (EdD) by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ George Fox University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. PEDAGOGY FOR CHRISTIAN WORLDVIEW FORMATION: A GROUNDED THEORY STUDY OF BIBLE COLLEGE TEACHING METHODS by ROB LINDEMANN FACULTY RESEARCH COMMITTEE: Chair: Patrick Allen, PhD Members: Terry Huffman, PhD, Ken Badley, PhD A dissertation presented to the Doctoral Department and College of Education, George Fox University. In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Education April 12, 2016 ii ABSTRACT To date, only emerging qualitative data exist on pedagogy employed specifically for worldview formation, especially in Christian contexts. Using a grounded theory approach, I carried out this qualitative research using personal interviews with the goal of discovering a theory for the processes expert teachers use in employing effective worldview pedagogy. Data was gathered through personal interviews with six participants who were nominated by their presidents or deans as suitable candidates according to the criteria of an expert teacher in this aspect of Bible college teaching. -

An Engagement with God's World: the Core Curriculum of Calvin College

An Engagement with God’s World: the Core Curriculum of Calvin College A Statement of Purpose A Curricular Structure A Series of Policies and Procedures Adopted by the Calvin College Faculty: November 3, 1997 March 15, 1999 April 5, 1999 November 20, 2000 April 3, 2006 An Engagement with God’s World CHAPTER ONE: A Statement of Purpose for the Core Curriculum of Calvin College 1.1 Preface Among the many pieces of advice given in the literature on general education reform, two stand out as both sound and of particular relevance to the formulation of a statement of purpose for the core curriculum. One is that, before embarking on any reform or revision of its general education program, an institution should be clear about the purpose of general education. The second is that the purpose of a general education program should be fitted to an institution’s understanding of its particular mission as shaped by its tradition. These points are well taken, and so we preface the statement of purpose for the core curriculum with a brief reflection on Calvin’s mission and identity. 1.2 The Christian Mission of Calvin College OF THE SEVERAL FORMULATIONS OF EDUCATIONAL MISSION to be found in Calvin’s Expanded Statement of Mission, none is more succinct or more precise than the following: “Calvin College seeks to engage in vigorous liberal arts education that promotes lives of Christian service” (ESM, p. 33). The distinctive feature of this mission is not vigorous liberal arts education; for hundreds of institutions of higher education across the North American continent are engaged in that very project. -

Worldview: the History of a Concept (Book Review)

Volume 32 Number 3 Article 5 March 2004 Worldview: The History of a Concept (Book Review) Tim McConnel Dordt College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcollections.dordt.edu/pro_rege Recommended Citation McConnel, Tim (2004) "Worldview: The History of a Concept (Book Review)," Pro Rege: Vol. 32: No. 3, 41 - 43. Available at: https://digitalcollections.dordt.edu/pro_rege/vol32/iss3/5 This Book Review is brought to you for free and open access by the University Publications at Digital Collections @ Dordt. It has been accepted for inclusion in Pro Rege by an authorized administrator of Digital Collections @ Dordt. For more information, please contact [email protected]. in their technicistic views of the future. But Fukuyama reading for Christians who are interested in where our tech- raises good arguments, and his failure to convince ought to nological efforts may take us in the future. Brooks will be encourage Christians to become active in developing a more interesting to computer scientists and engineers. But Christian philosophy of technology, where insights and Fukuyama’s book is very well written, and thus will appeal understanding might be developed on the firm foundation to all those who generally would not wish to see their “too of the Word of God. too solid flesh” melt, thaw, and resolve itself into a posthu- Both Brooks’s and Fukuyama’s books are well worth man dew. Worldview: The History of a Concept, by David K. Naugle. Grand Rapids, MI: William B. Eerdmans Publishing Company, 2002. xxii + 384 pp. Reviewed by Tim McConnel, Assistant Professor of Theology, Dordt College. -

'Colony of Heaven': Abraham Kuyper's Ecclesiology in the Twenty-First Century

Journal of Markets & Morality Volume 17, Number 2 (Fall 2014): 445–490 Copyright © 2014 ‘Colony of Heaven’: Abraham Kuyper’s Ecclesiology in the Twenty-First Ad de Bruijne Century Theologische Universiteit Kampen This article offers a concise exposition of the ecclesiology of Abraham Kuyper. Focusing extensively on Kuyper’s doctrines of the church as both institute and organism as well as on ecclesiological pluriformity, the enduring relevance of Kuyper’s vision is shown for our present context, both in the Netherlands and the United States. Contrary to neo-Calvinist critiques of the twentieth century, the term institute is just as contextually bound as organism—yet this does not negate the usefulness of either concept. Rather, it is the task of the church to adapt itself to the concrete circumstances of each place and age, even employing ideas from each context as appropriate. With reservations regarding his neglect of the liturgi- cal character of the church, Kuyper’s distinctions are expounded and set forward as helpful ecclesiological guidelines for modern Christian social witness today. Introduction: Kuyper’s Ecclesiology Today? What could the meaning of the ecclesiology of Abraham Kuyper be in the twenty-first century? Most of Kuyper’s writings about the church originate in the nineteenth century and mark important moments in the development of Kuyper’s ecclesial thought. Kuyper’s ecclesiology was closely related to its own context. For example, the most comprehensive of these writings, the Tractaat, does not consist of a balanced discourse on the nature of the church but primarily offers a theological justification of theDoleantie , a church secession that Kuyper would initiate only a few years later. -

All Things New: Neo-Calvinist Groundings for Social Work

ARTICLES All Things New: Neo-Calvinist Groundings for Social Work James R. Vanderwoerd “There will be no more death or mourning or crying or pain…. See, I am making all things new.” This vision from Revelation 21—perhaps the most comforting words a Christian in social work will ever hear—provides a beacon of hope in the face of despair. This article grounds this hopeful vision within Reformed Christianity, specifically within the neo-Calvinist tradition, and highlights contributions of this tradition to social work and social welfare. N 1891, A BRAHAM K UYPER GAVE THE KEYNOTE ADDRESS AT THE FIRST Christian Social Congress in the Netherlands. The burning question Ion the minds of Christians across Europe was what to do about the torrent of social problems erupting in cities across the western world. Two emerging approaches battled for supremacy, each promising a golden future: capitalism and socialism. Both approaches rested upon the twin foundations of human autonomy and scientific rationality. Both approaches explicitly rejected God and the millennia-old traditions of Christianity as hopelessly outdated for the complex social problems at the dawn of the 20 th century. In this context, Abraham Kuyper emerged as a Christian David fighting a secular Goliath. Vehemently rejecting humanist diagnoses and solutions, Kuyper (2011/1891) unapologetically declared: We as Christians must place the strongest possible empha- sis on the majesty of God’s authority and on the absolute validity of his ordinances, so that, even as we condemn the rotting social structure of our day, we will never try to erect any structure except one that rests on foundations laid by God (p. -

Epistemology and Presuppositional Thought

Southeastern University FireScholars Selected Honors Theses Spring 2019 EPISTEMOLOGY AND PRESUPPOSITIONAL THOUGHT Courtney L. Krause Southeastern University - Lakeland Follow this and additional works at: https://firescholars.seu.edu/honors Part of the Biblical Studies Commons, Practical Theology Commons, and the Religious Thought, Theology and Philosophy of Religion Commons Recommended Citation Krause, Courtney L., "EPISTEMOLOGY AND PRESUPPOSITIONAL THOUGHT" (2019). Selected Honors Theses. 104. https://firescholars.seu.edu/honors/104 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by FireScholars. It has been accepted for inclusion in Selected Honors Theses by an authorized administrator of FireScholars. For more information, please contact [email protected]. EPISTEMOLOGY AND PRESUPPOSITIONAL THOUGHT by Courtney Krause Submitted to the School of Honors Committee in partial fulfillment of the requirements for University Honors Scholars Southeastern University 2019 i Copyright by Courtney Krause 2019 ii Dedication Dedicated to my uncle, Jeffery Krause. Thank you for inspiring me and challenging my thoughts. You introduced me to Reformed theology, and my understanding of the God of Scripture will never be the same. I am more appreciative than I am able to express for your example to our family and your passion to teach the Word of God. iii Acknowledgements I must acknowledge and thank my Lord Jesus Christ. Thank you to my family and friends, who have contributed so much to my growth and understanding over the years. Thank you to my thesis advisor, Dr. Joseph Davis. The confidence and patience which you have instilled in me throughout this project has been priceless. I am truly grateful. Thank you to Professor Yoon Shin for each book you have allowed me to borrow from your library. -

Christian Students' Worldviewsand Propensity for Missionteaching

CHRISTIAN STUDENTS’ WORLDVIEWS AND PROPENSITY FOR MISSION TEACHING by Richard Patrick Dolan Liberty University A Dissertation Presented in Partial Fulfillment Of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Education Liberty University December, 2010 ii Christian Students’ Worldviews and Propensity for Mission Teaching by Richard Patrick Dolan A Dissertation Presented in Partial Fulfillment Of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Education Liberty University, Lynchburg, VA December, 2010 APPROVED: COMMITTTEE CHAIR Samuel J. Smith, Ed.D. COMMITTEE MEMBERS Kenneth G. Cleaver, Ph.D. Jeffrey S. Savage, Ed.D. CHAIR, GRADUATE STUDIES Scott Watson, Ph.D. iii ABSTRACT Richard Patrick Dolan. CHRISTIAN STUDENTS’ WORLDVIEWS AND PROPENSITY FOR MISSION TEACHING. (Under the direction of Dr. Samuel J. Smith) School of Education, December, 2010. The research conducted sought to find evidence to answer the following questions: Do students in teacher preparation programs who feel called to enter the Christian mission field as general education teachers have a worldview that is more closely aligned with biblical principles than other teacher groups? Is there a correlation between the worldview of mission general education teachers and propensity to volunteer for the field? What do students consider as influence in their decisions to commit to the Christian mission service profession? The data gathered indicated that participants who intended to volunteer at mission schools had significantly higher scores in all the types of worldview than participants with no such intention. All of the worldview scores were highly and directly correlated with propensity to volunteer. The results of the qualitative supplement indicate that influential persons and life changing events are important to their decisions to work in a mission setting. -

Students' Evangelical Worldview in Public High

STUDENTS’ EVANGELICAL WORLDVIEW IN PUBLIC HIGH SCHOOL CONTENT AREAS: A PHENOMENOLOGICAL ANALYSIS by Russell Joseph Allen Liberty University A Dissertation Presented in Partial Fulfillment Of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Education Liberty University 2021 2 STUDENTS’ EVANGELICAL WORLDVIEW IN PUBLIC HIGH SCHOOL CONTENT AREAS: A PHENOMENOLOGICAL ANALYSIS by Russell Joseph Allen A Dissertation Presented in Partial Fulfillment Of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Education Liberty University, Lynchburg, VA 2021 APPROVED BY: L. Thomas Crites, Ed.D, Committee Chair Justin Necessary, Ed.D, Committee Member 3 ABSTRACT Although much research has been conducted regarding Christian worldview in private high schools and Christian colleges, very little information exists regarding Christian worldview at public high schools. The purpose of this transcendental phenomenological study is to describe how 10 evangelical students in public high schools interpret content areas through their worldview. The study answered the following critical question: How do evangelical students in public high schools interpret content areas through their worldviews? Participants were found using criterion sampling in central Pennsylvania and document analysis, interviews, and focus groups were used to collect data. Moustakas’s (1994) approach was used for data analysis, which includes epoché, horizonalization, textural and structural descriptions, and a composite description. Member checks, audits, and codebooks were used in order to ensure the trustworthiness of the study. The results of this transcendental phenomenological study showed that the participants experienced content interpretation through the themes of parallel, truth, presentation, and interpersonal relatability. While these interpretations of content were largely thoughtful and deep, students remained reluctant to express these understandings in the public school classroom. -

Intro to Abraham Kuyper

Dr. David Naugle Friday Symposium Dallas Baptist University February 2, 2001 The Lordship of Christ Over the Whole of Life: An Introduction to the Thought of Abraham Kuyper Described by his enemies as “an opponent of ten heads and a hundred hands,” and by his friends as “a gift of God to our age,”1 Abraham Kuyper (1837- 1920) was truly a homo universale, a veritable genius in both intellectual and practical affairs. A noted journalist, politician, educator, and theologian with mosaic vigor, he is especially remembered as the founder of the Free University of Amsterdam in 1880, and as the Prime Minister of the Netherlands from 1901-1905. The source of this man’s remarkable contributions is found in a powerful spiritual vision derived from the theology of the protestant reformers (primarily Calvin) which centered upon the sovereignty of the biblical God over all aspects of reality, life, thought, and culture. Indeed, as he thundered in the climax to his inaugural address at the dedication of the Free University, “there is not a square inch in the whole domain of our human existence over which Christ, who is Sovereign over all, does not cry: ‘Mine!’”2 On the basis of this theological axiom, Kuyper drew inspiration for the all-consuming goal of his life, namely the renewal of the Dutch church and nation, expressed in these often quoted words. One desire has been the ruling passion of my life. One high motive has acted like a spur upon my mind and soul. And sooner than that I should seek escape from the sacred necessity that this is laid upon me, let the breath of life fail me.