Achilles and the Batman on the Plane of Immanence: Deconstructing Heroic Models

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Bill Rogers Collection Inventory (Without Notes).Xlsx

Title Publisher Author(s) Illustrator(s) Year Issue No. Donor No. of copies Box # King Conan Marvel Comics Doug Moench Mark Silvestri, Ricardo 1982 13 Bill Rogers 1 J1 Group Villamonte King Conan Marvel Comics Doug Moench Mark Silvestri, Ricardo 1982 14 Bill Rogers 1 J1 Group Villamonte King Conan Marvel Comics Doug Moench Ricardo Villamonte 1982 12 Bill Rogers 1 J1 Group King Conan Marvel Comics Doug Moench Alan Kupperberg and 1982 11 Bill Rogers 1 J1 Group Ernie Chan King Conan Marvel Comics Doug Moench Ricardo Villamonte 1982 10 Bill Rogers 1 J1 Group King Conan Marvel Comics Doug Moench John Buscema, Ernie 1982 9 Bill Rogers 1 J1 Group Chan King Conan Marvel Comics Roy Thomas John Buscema and Ernie 1981 8 Bill Rogers 1 J1 Group Chan King Conan Marvel Comics Roy Thomas John Buscema and Ernie 1981 6 Bill Rogers 1 J1 Group Chan Conan the King Marvel Don Kraar Mike Docherty, Art 1988 33 Bill Rogers 1 J1 Nnicholos King Conan Marvel Comics Roy Thomas John Buscema, Danny 1981 5 Bill Rogers 2 J1 Group Bulanadi King Conan Marvel Comics Roy Thomas John Buscema, Danny 1980 3 Bill Rogers 1 J1 Group Bulanadi King Conan Marvel Comics Roy Thomas John Buscema and Ernie 1980 2 Bill Rogers 1 J1 Group Chan Conan the King Marvel Don Kraar M. Silvestri, Art Nichols 1985 29 Bill Rogers 1 J1 Conan the King Marvel Don Kraar Mike Docherty, Geof 1985 30 Bill Rogers 1 J1 Isherwood, Mike Kaluta Conan the King Marvel Don Kraar Mike Docherty, Geof 1985 31 Bill Rogers 1 J1 Isherwood, Mike Kaluta Conan the King Marvel Don Kraar Mike Docherty, Vince 1986 32 Bill Rogers -

Gotham Knights

University of Denver Digital Commons @ DU Electronic Theses and Dissertations Graduate Studies 11-1-2013 House of Cards Matthew R. Lieber University of Denver Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.du.edu/etd Part of the Screenwriting Commons Recommended Citation Lieber, Matthew R., "House of Cards" (2013). Electronic Theses and Dissertations. 367. https://digitalcommons.du.edu/etd/367 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate Studies at Digital Commons @ DU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ DU. For more information, please contact [email protected],[email protected]. House of Cards ____________________________ A Thesis Presented to the Faculty of Social Sciences University of Denver ____________________________ In Partial Requirement of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts ____________________________ By Matthew R. Lieber November 2013 Advisor: Sheila Schroeder ©Copyright by Matthew R. Lieber 2013 All Rights Reserved Author: Matthew R. Lieber Title: House of Cards Advisor: Sheila Schroeder Degree Date: November 2013 Abstract The purpose of this thesis is to approach adapting a comic book into a film in a unique way. With so many comic-to-film adaptations following the trends of action movies, my goal was to adapt the popular comic book, Batman, into a screenplay that is not an action film. The screenplay, House of Cards, follows the original character of Miranda Greene as she attempts to understand insanity in Gotham’s most famous criminal, the Joker. The research for this project includes a detailed look at the comic book’s publication history, as well as previous film adaptations of Batman, and Batman in other relevant media. -

HOMERIC-ILIAD.Pdf

Homeric Iliad Translated by Samuel Butler Revised by Soo-Young Kim, Kelly McCray, Gregory Nagy, and Timothy Power Contents Rhapsody 1 Rhapsody 2 Rhapsody 3 Rhapsody 4 Rhapsody 5 Rhapsody 6 Rhapsody 7 Rhapsody 8 Rhapsody 9 Rhapsody 10 Rhapsody 11 Rhapsody 12 Rhapsody 13 Rhapsody 14 Rhapsody 15 Rhapsody 16 Rhapsody 17 Rhapsody 18 Rhapsody 19 Rhapsody 20 Rhapsody 21 Rhapsody 22 Rhapsody 23 Rhapsody 24 Homeric Iliad Rhapsody 1 Translated by Samuel Butler Revised by Soo-Young Kim, Kelly McCray, Gregory Nagy, and Timothy Power [1] Anger [mēnis], goddess, sing it, of Achilles, son of Peleus— 2 disastrous [oulomenē] anger that made countless pains [algea] for the Achaeans, 3 and many steadfast lives [psūkhai] it drove down to Hādēs, 4 heroes’ lives, but their bodies it made prizes for dogs [5] and for all birds, and the Will of Zeus was reaching its fulfillment [telos]— 6 sing starting from the point where the two—I now see it—first had a falling out, engaging in strife [eris], 7 I mean, [Agamemnon] the son of Atreus, lord of men, and radiant Achilles. 8 So, which one of the gods was it who impelled the two to fight with each other in strife [eris]? 9 It was [Apollo] the son of Leto and of Zeus. For he [= Apollo], infuriated at the king [= Agamemnon], [10] caused an evil disease to arise throughout the mass of warriors, and the people were getting destroyed, because the son of Atreus had dishonored Khrysēs his priest. Now Khrysēs had come to the ships of the Achaeans to free his daughter, and had brought with him a great ransom [apoina]: moreover he bore in his hand the scepter of Apollo wreathed with a suppliant’s wreath [15] and he besought the Achaeans, but most of all the two sons of Atreus, who were their chiefs. -

Superman Unchained: the New 52 Free

FREE SUPERMAN UNCHAINED: THE NEW 52 PDF Scott Snyder,Jim Lee | 240 pages | 14 Jan 2015 | DC Comics | 9781401245221 | English | United States The New 52 - Wikipedia Uh-oh, it looks like your Internet Explorer is out of date. For a better shopping experience, please upgrade now. Javascript is not enabled in your browser. Enabling JavaScript in your browser will allow you to experience all the features of our site. Learn how to enable JavaScript on your browser. Home 1 Books 2. Add to Wishlist. Sign in to Purchase Instantly. Members save with free shipping everyday! See details. Overview Decades before the Last Son of Krypton became Earth's champion, another being of incredible power fell from the sky. His role in humanity's deadliest conflict became America's darkest secret. Now the secret is out. And this super soldier has been unchained once more. The Man of Steel. His arch-enemy, Lex Luthor. His close confidant, Lois Lane. Her Superman Unchained: The New 52 father, General Sam Lane. Techno-terrorists with a Superman Unchained: The New 52 link to the past. All of them will vie for control of this hidden engine of destruction. Product Details About the Author. About the Author. He is a dedicated and un-ironic fan of Elvis Presley. Related Searches. View Product. In this final team-up issue, all-out war has broken out in the streets of Shamba-La! The worlds of Batman and the legendary vigilante the Shadow collide in this crossover for The worlds of Batman and the legendary vigilante the Shadow collide in this crossover for the ages, now available in paperback! From the incredible minds of iconic authors Scott Snyder and Steve Orlando comes the resurgence of a classic noir character. -

What Is FOP? a Guidebook for Families)

What is FOP? Fibrodysplasia Ossifi cans Progressiva A Guidebook for Families © International FOP Association (IFOPA) • Winter Springs, Florida Th ird Edition, 2009 Editor: Sharon Kantanie Medical Editors: Patricia L.R. Delai, M.D., Frederick S. Kaplan, M.D., Eileen M. Shore, Ph.D. ii r This book is dedicated to all of the families who live with FOP every day. iii About the cover The painting on the cover of this book is called ‘‘The Circle of Life.’’ I had a number of reasons for picking this title for my butterfly painting. The butterfly to me is a symbol of hope and new beginnings. It is a subject that everyone can relate to, and everyone has seen a butterfly. Showing the cycle of the monarch butterfly tells of the changes in life which also occur with FOP. I picked the detailed work of a butterfly in watercolor to show what can be done after my adapting to FOP. I was a right handed painter until two years ago when my right elbow locked, forcing me to now do most of my painting with my left hand. This painting was the first time I had painted an open-winged monarch butterfly using my left hand. I consider this one of the more difficult butterflies to paint. Through my artwork, I also want to show with my painting that people with FOP can have productive lives. It’s important to have a special interest such as painting is to me. Jack B. Sholund Bigfork, Minnesota 1995 (for the first edition of What is FOP? A Guidebook for Families) iv Contents Foreword ....................................................... -

Blackest Night / Brightest Day Jumpchain What Is Death in a World

Blackest Night / Brightest Day Jumpchain What is death in a world like this one? Great heroes and villains alike have tasted the sweet kiss of oblivion, both deserving and not. Yet death has also been defied, and many more have returned to life through circumstance or miracle. Two heroes in particular – Hal Jordan, a Green Lantern of Earth, and Barry Allen, The Flash, both ponder this together as they talk over the gravestone of Bruce Wayne. Both had died and returned to life before. And soon, many more will return as well...but not in a way they or anyone else would expect. Recently, the Green Lantern Corps, a peacekeeping organization created by the self-touted Guardians of the Universe, have been at war with the Sinestro Corps founded by its namesake rogue who fell from grace in the past. As this conflict raged on, other Lantern Corps were discovered or created as all seven colors on the Emotional Spectrum were revealed to the galaxy. But as this conflict and chaos rages on, a prophecy is fulfilled and as the various colors come into battle with each other, a darker force awakens. The Entity of Death, Nekron, acting through the villain Death’s Hand, has prepared to unleash a plague on the entire universe. One that will see the billions of dead across all of creation rise and seek to ravage the living, before extinguishing all life entirely within the Blackest Night. Just as this conversation began, you appear. You are a new or veteran member of one of the existing Lantern Corps...unless you are a Black Lantern, in which you rise from death not long after as the crisis of the Blackest Night begins. -

Legends of the Dark Knight: Norm Breyfogle: Volume 1 Free Ebook

FREELEGENDS OF THE DARK KNIGHT: NORM BREYFOGLE: VOLUME 1 EBOOK Norm Breyfogle,Alan Grant | 520 pages | 04 Aug 2015 | DC Comics | 9781401258986 | English | United States Legends of the Dark Knight: Norm Breyfogle #1 - Volume 1 (Issue) Goodreads helps you keep track of books you want to read. Want to Read saving…. Want to Read Currently Reading Read. Other editions. Enlarge cover. Error rating book. Refresh and try again. Open Preview See a Problem? Details if other :. Thanks for telling us about the problem. Return to Book Page. Alan Grant. John Wagner. Mike W. Barr. Jo Duffy. Robert Greenberger Goodreads Author. Batman AnnualDetective Comics, Get A Copy. Hardcoverpages. More Details Other Editions 4. Friend Reviews. To see what your friends thought of this book, please sign up. To ask other readers questions about Legends of the Dark Knightplease sign up. Be the first to ask a question about Legends of the Dark Knight. Lists with This Book. Community Reviews. Showing Average rating 4. Rating details. More filters. Sort order. Mar 28, Keith rated it really liked it. So man, I have been waiting for this collection to exist for over 20 years. Batman which isn't collected here, but should be in subsequent volumes was my first-ever Batman comic, and I reread it so many times in the intervening years I'm pretty sure I have it memorized. From that book forward, I was absolutely addicted to Norm Breyfogle's Batman -- the harsh angles, the incredible page layouts, the mix of narrative storytelling ability and an aggressive dynamism that I just don't even kno So man, I have been waiting for this collection to exist for over 20 years. -

Osric: Waterfly, Lapwing, Chough, and Claudius's Final Instrument Osric Is

Osric: Waterfly, Lapwing, Chough, and Claudius’s Final Instrument Osric is a late-entering character, like the Gravediggers and Fortinbras, but like the latter, he is crucial to the play’s finale. He does not show his face until most of the king’s tools—the meddlesome Polonius as well as Rosencrantz and Guildenstern— have found out that “to be too busy is some danger.” Osric’s entry takes audiences by surprise, and it is only after a good deal of distractingly amusing repartee with Hamlet that he mentions Laertes, the fencing match, or the king’s “wager.”1 But audiences know that Osric’s business is somehow connected with the mousetrap that the king and Laertes have elaborately fashioned for Hamlet, and they are acutely aware that it is Laertes himself, at his own request to be Claudius’s “instrument,” who will be physically wielding the instrument of premeditated murder. Osric, then, seems a shadow-Laertes, a figure with his own agenda of advancement who is also being used by Claudius to lure Hamlet into the final duel. Though a minor character, a mere court functionary satirized as the apotheosis of courtly decadence, Osric is the last and surely the most idiosyncratic and puzzling in a long line of those whom the king has used for his deadly purposes—and the only survivor. There are different emphases and opinions about details of Osric’s ostentatious “words, words, words” and of Shakespeare’s grander design in sending such an emissary from the king, but there is little critical disagreement about the basic character of Osric—his buffoonish sycophancy and its comic/satirical ramifications—as he makes his first appearance in 5.2. -

The Digital Deli Online - List of Known Available Shows As of 01-01-2003

The Digital Deli Online - List of Known Available Shows as of 01-01-2003 $64,000 Question, The 10-2-4 Ranch 10-2-4 Time 1340 Club 150th Anniversary Of The Inauguration Of George Washington, The 176 Keys, 20 Fingers 1812 Overture, The 1929 Wishing You A Merry Christmas 1933 Musical Revue 1936 In Review 1937 In Review 1937 Shakespeare Festival 1939 In Review 1940 In Review 1941 In Review 1942 In Revue 1943 In Review 1944 In Review 1944 March Of Dimes Campaign, The 1945 Christmas Seal Campaign 1945 In Review 1946 In Review 1946 March Of Dimes, The 1947 March Of Dimes Campaign 1947 March Of Dimes, The 1948 Christmas Seal Party 1948 March Of Dimes Show, The 1948 March Of Dimes, The 1949 March Of Dimes, The 1949 Savings Bond Show 1950 March Of Dimes 1950 March Of Dimes, The 1951 March Of Dimes 1951 March Of Dimes Is On The Air, The 1951 March Of Dimes On The Air, The 1951 Packard Radio Spots 1952 Heart Fund, The 1953 Heart Fund, The 1953 March Of Dimes On The Air 1954 Heart Fund, The 1954 March Of Dimes 1954 March Of Dimes Is On The Air With The Fabulous Dorseys, The 1954 March Of Dimes Is On The Air, The 1954 March Of Dimes On The Air 1955 March Of Dimes 1955 March Of Dimes Is On The Air, The 1955 March Of Dimes, The 1955 Pennsylvania Cancer Crusade, The 1956 Easter Seal Parade Of Stars 1956 March Of Dimes Is On The Air, The 1957 Heart Fund, The 1957 March Of Dimes Galaxy Of Stars, The 1957 March Of Dimes Is On The Air, The 1957 March Of Dimes Presents The One and Only Judy, The 1958 March Of Dimes Carousel, The 1958 March Of Dimes Star Carousel, The 1959 Cancer Crusade Musical Interludes 1960 Cancer Crusade 1960: Jiminy Cricket! 1962 Cancer Crusade 1962: A TV Album 1963: A TV Album 1968: Up Against The Establishment 1969 Ford...It's The Going Thing 1969...A Record Of The Year 1973: A Television Album 1974: A Television Album 1975: The World Turned Upside Down 1976-1977. -

Alter Ego #78 Trial Cover

TwoMorrows Publishing. Celebrating The Art & History Of Comics. SAVE 1 NOW ALL WHE5% O N YO BOOKS, MAGS RDE U & DVD s ARE ONL R 15% OFF INE! COVER PRICE EVERY DAY AT www.twomorrows.com! PLUS: New Lower Shipping Rates . s r Online! e n w o e Two Ways To Order: v i t c e • Save us processing costs by ordering ONLINE p s e r at www.twomorrows.com and you get r i e 15% OFF* the cover prices listed here, plus h t 1 exact weight-based postage (the more you 1 0 2 order, the more you save on shipping— © especially overseas customers)! & M T OR: s r e t • Order by MAIL, PHONE, FAX, or E-MAIL c a r at the full prices listed here, and add $1 per a h c l magazine or DVD and $2 per book in the US l A for Media Mail shipping. OUTSIDE THE US , PLEASE CALL, E-MAIL, OR ORDER ONLINE TO CALCULATE YOUR EXACT POSTAGE! *15% Discount does not apply to Mail Orders, Subscriptions, Bundles, Limited Editions, Digital Editions, or items purchased at conventions. We reserve the right to cancel this offer at any time—but we haven’t yet, and it’s been offered, like, forever... AL SEE PAGE 2 DIGITIITONS ED E FOR DETAILS AVAILABL 2011-2012 Catalog To get periodic e-mail updates of what’s new from TwoMorrows Publishing, sign up for our mailing list! ORDER AT: www.twomorrows.com http://groups.yahoo.com/group/twomorrows TwoMorrows Publishing • 10407 Bedfordtown Drive • Raleigh, NC 27614 • 919-449-0344 • FAX: 919-449-0327 • e-mail: [email protected] TwoMorrows Publishing is a division of TwoMorrows, Inc. -

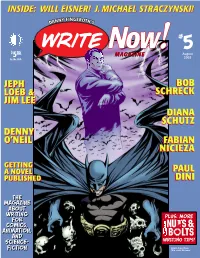

Inside: Will Eisner! J. Michael Straczynski!

IINNSSIIDDEE:: WWIILLLL EEIISSNNEERR!! JJ.. MMIICCHHAAEELL SSTTRRAACCZZYYNNSSKKII!! $ 95 MAGAAZZIINEE August 5 2003 In the USA JJEEPPHH BBOOBB LLOOEEBB && SSCCHHRREECCKK JJIIMM LLEEEE DIANA SCHUTZ DDEENNNNYY OO’’NNEEIILL FFAABBIIAANN NNIICCIIEEZZAA GGEETTTTIINNGG AA NNOOVVEELL PPAAUULL PPUUBBLLIISSHHEEDD DDIINNII Batman, Bruce Wayne TM & ©2003 DC Comics MAGAZINE Issue #5 August 2003 Read Now! Message from the Editor . page 2 The Spirit of Comics Interview with Will Eisner . page 3 He Came From Hollywood Interview with J. Michael Straczynski . page 11 Keeper of the Bat-Mythos Interview with Bob Schreck . page 20 Platinum Reflections Interview with Scott Mitchell Rosenberg . page 30 Ride a Dark Horse Interview with Diana Schutz . page 38 All He Wants To Do Is Change The World Interview with Fabian Nicieza part 2 . page 47 A Man for All Media Interview with Paul Dini part 2 . page 63 Feedback . page 76 Books On Writing Nat Gertler’s Panel Two reviewed . page 77 Conceived by Nuts & Bolts Department DANNY FINGEROTH Script to Pencils to Finished Art: BATMAN #616 Editor in Chief Pages from “Hush,” Chapter 9 by Jeph Loeb, Jim Lee & Scott Williams . page 16 Script to Finished Art: GREEN LANTERN #167 Designer Pages from “The Blind, Part Two” by Benjamin Raab, Rich Burchett and Rodney Ramos . page 26 CHRISTOPHER DAY Script to Thumbnails to Printed Comic: Transcriber SUPERMAN ADVENTURES #40 STEVEN TICE Pages from “Old Wounds,” by Dan Slott, Ty Templeton, Michael Avon Oeming, Neil Vokes, and Terry Austin . page 36 Publisher JOHN MORROW Script to Finished Art: AMERICAN SPLENDOR Pages from “Payback” by Harvey Pekar and Dean Hapiel. page 40 COVER Script to Printed Comic 2: GRENDEL: DEVIL CHILD #1 Penciled by TOMMY CASTILLO Pages from “Full of Sound and Fury” by Diana Schutz, Tim Sale Inked by RODNEY RAMOS and Teddy Kristiansen . -

Kirby: the Wonderthe Wonderyears Years Lee & Kirby: the Wonder Years (A.K.A

Kirby: The WonderThe WonderYears Years Lee & Kirby: The Wonder Years (a.k.a. Jack Kirby Collector #58) Written by Mark Alexander (1955-2011) Edited, designed, and proofread by John Morrow, publisher Softcover ISBN: 978-1-60549-038-0 First Printing • December 2011 • Printed in the USA The Jack Kirby Collector, Vol. 18, No. 58, Winter 2011 (hey, it’s Dec. 3 as I type this!). Published quarterly by and ©2011 TwoMorrows Publishing, 10407 Bedfordtown Drive, Raleigh, NC 27614. 919-449-0344. John Morrow, Editor/Publisher. Four-issue subscriptions: $50 US, $65 Canada, $72 elsewhere. Editorial package ©2011 TwoMorrows Publishing, a division of TwoMorrows Inc. All characters are trademarks of their respective companies. All artwork is ©2011 Jack Kirby Estate unless otherwise noted. Editorial matter ©2011 the respective authors. ISSN 1932-6912 Visit us on the web at: www.twomorrows.com • e-mail: [email protected] All rights reserved. No portion of this publication may be reproduced in any manner without permission from the publisher. (above and title page) Kirby pencils from What If? #11 (Oct. 1978). (opposite) Original Kirby collage for Fantastic Four #51, page 14. Acknowledgements First and foremost, thanks to my Aunt June for buying my first Marvel comic, and for everything else. Next, big thanks to my son Nicholas for endless research. From the age of three, the kid had the good taste to request the Marvel Masterworks for bedtime stories over Mother Goose. He still holds the record as the youngest contributor to The Jack Kirby Collector (see issue #21). Shout-out to my partners in rock ’n’ roll, the incomparable Hitmen—the best band and best pals I’ve ever had.