In Black and White by Joe Flanagan

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

View PDF Datastream

Society of Architectural Historians University of California Press "The Century's Triumph in Lighting": The Luxfer Prism Companies and Their Contribution to Early Modern Architecture Author(s): Dietrich Neumann Source: Journal of the Society of Architectural Historians, Vol. 54, No. 1 (Mar., 1995), pp. 24-53 Published by: University of California Press on behalf of the Society of Architectural Historians Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/991024 Accessed: 25-10-2015 18:45 UTC Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at http://www.jstor.org/page/ info/about/policies/terms.jsp JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. Society of Architectural Historians and University of California Press are collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Journal of the Society of Architectural Historians. http://www.jstor.org This content downloaded from 128.148.252.35 on Sun, 25 Oct 2015 18:45:40 UTC All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions "The Century'sTriumph in Lighting": The Luxfer Prism Companies and their Contributionto Early Modem Architecture medium to another, as from air to water or, in this case, glass. DIETRICH NEUMANN, BrownUniversity Throughoutthe eighteenth and nineteenth centuriesconically characterize this new prism as one of the most shaped glassesalready had been used to redirectlight into dark .L remarkable improvements of the century in its bearing rooms in basementsor in ships.5Thaddeus Hyatt, one of the on practical architecture, is to speak but mildly. -

Download the Complete Architecture of Adler and Sullivan, Richard

The Complete Architecture of Adler and Sullivan, Richard Nickel, Aaron Siskind, Richard Nickel Committee, 2010, 0966027329, 9780966027327, 461 pages. В Louis Sullivan (1856–1924) was a giant of architecture, the father of architectural modernism, and one of the earliest builders of the skyscraper. Along with Dankmar Adler (1844–1900) he designed many of the buildings that defined nineteenth-century architecture not only in Chicago but in cities across AmericaвЂ―and continue to be admired today. Among their iconic designs are the former Chicago Stock Exchange, Chicago’s Auditorium Building and Carson Pirie Scott flagship store, the Wainwright Building in St. Louis, and the Guaranty Building in Buffalo. This first-of-its-kind catalogue raisonnГ© of the work of Adler and SullivanвЂ―both as a team and individual architectsвЂ―is a lavish celebration of the designs of these two seminal architects who paved the way for the modern skylines that continue to inspire city dwellers today. The quest to pull together a complete catalogue of their work was first undertaken in 1952 by photographer Aaron Siskind and Richard Nickel, one of his graduate students at what is now the Illinois Institute of Technology in Chicago. This intense, decades-long labor of love has resulted in an extensive and unique resource that includes a complete listing of all of the buildings and projects undertaken by Adler and Sullivan. Each listing contains historic photographs, architectural plans (when available), and a description of each project. Alongside over two and hundred fifty essays are eight hundred photographs of their buildingsвЂ―many of which have since been demolishedвЂ―including images by Nickel, Siskind, and other noted photographers. -

UPTOWN and ANDERSONVILLE Bike Tour, Sunday June Twentynine, Two Thousand Eight

UPTOWN AND ANDERSONVILLE bike tour, sunday june twentynine, two thousand eight. All Content Copyright © 2007-2008 Big Shoulders Realty, LLC. All Rights Reserved. uptown and andersonville bike tour Our Route, Part One uptown and andersonville bike tour Tour Part One – turn by turn instructions 1. Start at Graceland Cemetery, 4001 N Clark 22. Turn right heading north on Racine 2. Proceed east on Irving Park 23. Take a SHARP right, heading southeast on Broadway 3. Turn left heading north on Sheridan 24. Turn right heading west on Montrose 4. Take a SHARP right heading south on Broadway 25. Turn right heading north on Clifton, which curves to the left 5. Turn left, heading east on Irving Park 26. Turn left heading south on Racine 6. Turn left, heading north on Marine Dr. 27. Turn right heading west on Montrose 7. Turn left, heading west on Hutchinson 28. Turn right heading north on Beacon 8. Turn left, heading south on Hazel 29. Turn left, heading west on Leland 9. Turn left, heading east on Buena 30. Turn left, heading south on Dover 10. Turn left, heading north on Clarendon 31. Turn right, heading west on Wilson 11. Turn right heading east on Montrose 32. Turn right, heading north on Ashland 12. Stay on Montrose until after you cross under Lake Shore Drive. 33. Turn left, heading west on Lawrence 13. Then veer left onto the bike path. 34. Turn left, heading south on Paulina 14. The path will veer northeast up to the Lake 35. Turn right, heading west on Sunnyside 15. -

Chicago No 16

CLASSICIST chicago No 16 CLASSICIST NO 16 chicago Institute of Classical Architecture & Art 20 West 44th Street, Suite 310, New York, NY 10036 4 Telephone: (212) 730-9646 Facsimile: (212) 730-9649 Foreword www.classicist.org THOMAS H. BEEBY 6 Russell Windham, Chairman Letter from the Editors Peter Lyden, President STUART COHEN AND JULIE HACKER Classicist Committee of the ICAA Board of Directors: Anne Kriken Mann and Gary Brewer, Co-Chairs; ESSAYS Michael Mesko, David Rau, David Rinehart, William Rutledge, Suzanne Santry 8 Charles Atwood, Daniel Burnham, and the Chicago World’s Fair Guest Editors: Stuart Cohen and Julie Hacker ANN LORENZ VAN ZANTEN Managing Editor: Stephanie Salomon 16 Design: Suzanne Ketchoyian The “Beaux-Arts Boys” of Chicago: An Architectural Genealogy, 1890–1930 J E A N N E SY LV EST ER ©2019 Institute of Classical Architecture & Art 26 All rights reserved. Teaching Classicism in Chicago, 1890–1930 ISBN: 978-1-7330309-0-8 ROLF ACHILLES ISSN: 1077-2922 34 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS Frank Lloyd Wright and Beaux-Arts Design The ICAA, the Classicist Committee, and the Guest Editors would like to thank James Caulfield for his extraordinary and exceedingly DAVID VAN ZANTEN generous contribution to Classicist No. 16, including photography for the front and back covers and numerous photographs located throughout 43 this issue. We are grateful to all the essay writers, and thank in particular David Van Zanten. Mr. Van Zanten both contributed his own essay Frank Lloyd Wright and the Classical Plan and made available a manuscript on Charles Atwood on which his late wife was working at the time of her death, allowing it to be excerpted STUART COHEN and edited for this issue of the Classicist. -

Richard Nickel Studio 1810 W

LANDMARK DESIGNATION REPORT Richard Nickel Studio 1810 W. Cortland Street Final Landmark recommendation adopted by the Commission on Chicago Landmarks, April 1, 2010. CITY OF CHICAGO Richard M. Daley, Mayor Department of Zoning and Land Use Planning Patricia A. Scudiero, Commissioner The Commission on Chicago Landmarks, whose ten members are appointed by the Mayor and City Council, was established in 1968 by city ordinance. The Commission is responsible for recommend- ing to the City Council which individual buildings, sites, objects, or districts should be designated as Chicago Landmarks, which protects them by law. The landmark designation process begins with a staff study and a preliminary summary of information related to the potential designation criteria. The next step is a preliminary vote by the landmarks commission as to whether the proposed landmark is worthy of consideration. This vote not only initiates the formal designation process, but it places the review of city permits for the property under the jurisdiction of the Commission until a final landmark recommendation is acted on by the City Council. This Landmark Designation Report is subject to possible revision and amendment during the designation process. Only language contained within the designation ordinance adopted by the City Council should be regarded as final. Richard Nickel Studio 1810 W. Cortland Street Built: 1889 Architect: Unknown Period of Significance: 1969-1972 Constructed in 1889, the Richard Nickel Studio at 1810 W. Cortland St. was owned for a three-year-period from 1969 to1972 by architectural photographer Richard Nickel, a prominent and significant figure in the early historic preservation movement in Chicago. -

Inside This Issue

VOICE The Journal of Preservation Chicago WINTER 20 11 ISSUE No 10 INSIDE THIS ISSUE LATHROP HOMES REDEVELOPMENT STIRS CONTROVERSEY Page 3 READ THE LATEST PRESERVATION STATUS REPORT Page 6 8 SCHLITZ TAVERNS LANDMARKED Page 7 333 East Superior St., 1975, Bertrand Goldberg - Bertrand Goldberg and Associates Architect Photo Credit: Chicago History Museum CAN GOLDBERG’S MODERN MASTERPIECE BE SAVED? Perhaps the most overused word in the architectural principles, resulting in a uniquely original design lexicon is “unique”. It has been bandied about so philosophy. Rather than steel and glass, he adopted frequently that when a truly revolutionary piece of concrete as his medium; its plasticity the ideal architecture is built, the word loses all its meaning. material to realize his vision. Goldberg opined that However, in 1975, when Bertrand Goldberg’s Prentice there were no right angles in nature and strove to Women’s Pavilion opened on Chicago’s Northwestern create a more organic architecture, thus gravitating Hospital campus, the world witnessed the completion to more circular forms. of a structure that truly was unique. Now, merely 35 years old, this amazing masterwork is threatened Best known for his prescient Marina City, Goldberg with demolition. created a complete urban environment within a single development, a city within a city for urban Goldberg trained at Harvard and studied, for a time, professionals which provided affordable rental at the German Bauhaus under the direction of archi- housing, retail services, entertainment, and office -

An Analysis of Diverse Gentrification Processes and Their Relationship to Historic Preservation Activity in Three Chicago Neighborhoods

AN ANALYSIS OF DIVERSE GENTRIFICATION PROCESSES AND THEIR RELATIONSHIP TO HISTORIC PRESERVATION ACTIVITY IN THREE CHICAGO NEIGHBORHOODS By Ted Grevstad-Nordbrock A DISSERTATION Submitted to Michigan State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Geography – Doctor of Philosophy 2015 ABSTRACT AN ANALYSIS OF DIVERSE GENTRIFICATION PROCESSES AND THEIR RELATIONSHIP TO HISTORIC PRESERVATION ACTIVITY IN THREE CHICAGO NEIGHBORHOODS By Ted Grevstad-Nordbrock This dissertation explores the relationship between historic preservation and gentrification and how these forces have differentially shaped neighborhoods in Chicago over the period 1970-2000. It asks the two primary questions. First, to what extent is there evidence of diversity and complexity in the gentrification processes in Chicago where there have also been high levels of historic preservation activity? Second, what are some of the fundamental characteristics of these gentrification processes? This dissertation assesses whether public preservation programs have been facilitating gentrification in Chicago and helps clarify the long-debated relationship between preservation and gentrification. To explore these topics, principal component analysis and K-means cluster analysis are used to identify three suitable neighborhoods as case studies; each of these neighborhoods is then subjected to an in-depth, qualitative analysis. The findings of this research suggest that neighborhoods with different histories, populations, and urban morphologies use preservation programs in different ways to achieve different gentrification outcomes. Copyright by TED GREVSTAD-NORDBROCK 2015 For Anne, Fritz, and Karin iv ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Many thanks to my dissertation committee (Joe Darden, Zenia Kotval, Joe Messina, Bruce Pigozzi, Igor Vojnovic), to the staff and faculty of the geography department at MSU, and to my longtime colleagues at the Michigan State Historic Preservation Office and the erstwhile Office of the State Archaeologist. -

Adler and Sullivan Initially Achieved Fame As Theater Architects

Adler and Sullivan initially achieved fame as theater architects. While most of their theaters were in Chicago, their fame won commissions as far west as Pueblo, Colorado, and Seattle, Washington (unbuilt). The culminating project of this phase of the firm's history was the 1889 Auditorium Building in Chicago, an extraordinary mixed-use building which included not only a 3000-seat theater, but also a hotel and office building. Adler and Sullivan reserved the top floor of the tower for their own office. After 1889 the firm became known for their office buildings, particularly the 1891 Wainwright Building in St. Louis and the 1899 Carson Pirie Scott Department Store on State Street in Chicago, Louis Sullivan is considered by many to be the first architect to fully imagine and realize a rich architectural vocabulary for a revolutionary new kind of building: the steel high-rise. [edit] Sullivan and the steel high-rise Prior to the late 19th century, the weight of a multistory building had to be supported principally by the strength of its walls. The taller the building, the more strain this placed on the lower sections of the building; since there were clear engineering limits to the weight such "load-bearing" walls could sustain, large designs meant massively thick walls on the ground floors, and definite limits on the building's height. The development of cheap, versatile steel in the second half of the 19th century changed those rules. America was in the midst of rapid social and economic growth that made for great opportunities in architectural design. -

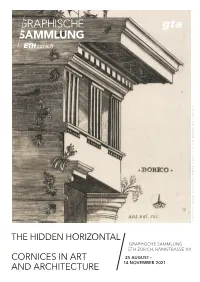

The Hidden Hori Zon Tal Cornices in Art And

cm, Graphische Sammlung ETH Zürich 13.6 × , 1530–1540, Kupferstich, 21.7 Dorisches Gesims Meister GA mit der Fussangel, THE HIDDEN HORI ZON TAL GRAPHISCHE SAMMLUNG ETH ZÜRICH, RÄMISTRASSE 101 CORNICES IN ART 25 AUGUST — AND ARCHITECTURE 14 NOVEMBER 2021 INTRODUCTION Cornices are everywhere. The skyline of any city street cultural phenomena recurring throughout history. is a ragtag procession of cornices in various states of These themes juxtapose works from different stylistic materiality, refinement and maintenance. Windows, movements, periods of history and geographies, doors, ceilings, mirrors and wall paneling from across encouraging visitors to survey enduring expressions the centuries sport elaborate profiles at their edges. of the cornice from multiple simultaneous perspec- Cars, clothes, furniture and household objects all fea- tives. ture their own cornice-like elements. Strips, bands and lines of paint act as cornices by framing, hemming or Curated by the Graphische Sammlung ETH Zürich, crowning almost any kind of artefact. In paintings, Dr. Linda Schädler, and the Chair of the History and etchings and photographs of buildings and streets, Theory of Architecture ETH Zürich (gta), Prof. Dr. cornices quietly structure the image and help to set Maarten Delbeke the scene for the life unfolding there. Assistant Curators: Anneke Abhelakh (gta), David Bühler (gta) and Dr. Emma Letizia Jones (formerly gta) Cornices tell stories about our histories. Drawing attention to the persistence of the cornice in European architecture and visual culture reflects broader cul- tural and aesthetic movements. As a crucial part of the classical repertoire of architecture, the cornice has been drawn, measured, designed, fabricated, con- structed and discussed ever since Antiquity. -

Newsletter the Society of Architectural Historians

NEWSLETTER THE SOCIETY OF ARCHITECTURAL HISTORIANS JUNE 1972 VOL. XVI NO. 3 PUBLISHED SIX TIMES A YEAR BY THE SOCIETY OF ARCHITECTURAL HISTORIANS 1700 Walnut Street, Philadelphia, Pa. 19103 • Alan Gowa ns, President • Editor: James C. Massey, 614 S. Lee Street, Alexa ndria, Virginia 22314 Asso. Ed.: Thomas M. Slade, 413 S. 26th St., South Bend, Indiana 46615 • Asst. Ed.: Elisabeth Walton, 765 Winter Sr., N.E. Salem, Oregon 97301 SAH NOTICES Committee thanks all those who have sent their ideas 1973 Annual Meeting-Foreign Tour (August 15-27). At already and urges those who have not yet done so to add this time, 85 of the 130 available places have been re their contributions. These expressions of interest will served on the charter flight (New York - London and be of great help in planning, and the Committee will be return). The September 10, 1972 deadline for registrations communicating further with members as plans develop for the Cambridge-London program has been set in case over the next few months. our Society needs any of the 100 provisional accommoda tions being held, o ver and above the 175 accommodations ORGANIZATIONS for which the SAH is committed to pay. In the event that the American Institute of Architects. At the convention of 175 accommodations have not been filled by September the American Institute of Architects in Houston, May 10, 1972, members of our Society may continue to register 7-10, historic architecture was emphasized at the Monday for the Cambridge-London program. A letter to the central morning Preservation Breakfast, an annual event presided office (1700 Walnut St., Room 716, Philadelphia, Pa. -

2007 Winter Extra

The Society of Architectural Historians News Missouri Valley Chapter Volume XIII Number 4B Winter—Extra 2007 Letter prove this property with a large office building. Both archi- THE ST. NICHOLAS HOTEL tects Isaac Taylor and Edmund Jungenfeld submitted plans AND THE VICTORIA BUILDING for the project, and the Estate selected Jungenfeld’s Gothic by David J. Simmons Revival design. Measuring 96 feet on Locust by 115 feet along Eighth Street, his Ames Building would rise eight During the period from 1890 to 1893, the architectural team stories above the ground floor, attaining a height of 118 of Adler & Sullivan designed nine projects for the St. Louis feet. At the corner of the building a tower extended upward market. Four of these commissions reached fruition and an additional 24 feet. Jungenfeld located the main entrance three survive today. The St. Nicholas Hotel lasted just one on Eighth Street. Besides the entrance hall and accessories decade before being rebuilt as an office building by Eames the ground floor contained four stores. Each floor above & Young. It has not received the appreciation or scholarly the ground story had 22 offices, for a total of 176. Other attention accorded to its three sister works (even the com- building features included an open light court in the rear, paratively little-known Union Trust Building). The under- two elevators, and cast iron staircases throughout. The cost standing of its history has been plagued by confusion, mis- was estimated at $200,000. In 1884, prior to the start of takes, and misconceptions. Dismissed by architectural pun- construction, Mr. -

Haddix Thesis Finalpdf.Pdf (5.806Mb)

SAVORING PLACE: PROTECTING CHICAGO’S SENSE OF PLACE BY PRESERVING ITS LEGACY RESTAURANTS. LEIGH A. HADDIX 2018 ABSTRACT Title of Thesis: SAVORING PLACE: PROTECTING CHICAGO’S SENSE OF PLACE BY PRESERVING ITS LEGACY RESTAURANTS Degree Candidate: Leigh Haddix Degree and Year: Master of Arts in Historic Preservation, 2018 Thesis Directed By: Betsy Bradley Welch Center for Graduate and Professional Studies Goucher College Humanist geographer Edward G. Relph in Place and Placelessness conceptualized a vision of place using a phenomenological approach based upon how humans experience place. Relph’s three main place components include Setting, Activity and Meaning, and considering resources in this manner can reframe preservation thought. Viewing place through Relph’s lens makes for a more holistic vision, that can shape what and how we preserve. A Relphian framework also provides a useful practice theory for preservationists to expand our notion of who performs preservation and how we evaluate sense of place. Small businesses are neighborhood anchors, and historic restaurants play a particularly social and experiential role. Tangible and intangible cultural heritage must be evaluated holistically when focusing preservation actions upon businesses such as historic restaurants. Legacy restaurants are place makers and visible markers of the layers of history within a place. They convey social history and foodways and act as expressions of the intangible cultural heritage that lends character to place. Change is a part of place; cuisine, the history of a place, and historic businesses do not remain static. Just as legacy business owners have had to be agile and adaptable to remain relevant and successful, historic preservation may work most effectively when it too is agile and adaptable in response to change.