Working Paper Series Paper 18

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Rebel Alliances

Rebel Alliances The means and ends 01 contemporary British anarchisms Benjamin Franks AK Pressand Dark Star 2006 Rebel Alliances The means and ends of contemporary British anarchisms Rebel Alliances ISBN: 1904859402 ISBN13: 9781904859406 The means amiemls 01 contemllOranr British anarchisms First published 2006 by: Benjamin Franks AK Press AK Press PO Box 12766 674-A 23rd Street Edinburgh Oakland Scotland CA 94612-1163 EH8 9YE www.akuk.com www.akpress.org [email protected] [email protected] Catalogue records for this book are available from the British Library and from the Library of Congress Design and layout by Euan Sutherland Printed in Great Britain by Bell & Bain Ltd., Glasgow To my parents, Susan and David Franks, with much love. Contents 2. Lenini8t Model of Class 165 3. Gorz and the Non-Class 172 4. The Processed World 175 Acknowledgements 8 5. Extension of Class: The social factory 177 6. Ethnicity, Gender and.sexuality 182 Introduction 10 7. Antagonisms and Solidarity 192 Chapter One: Histories of British Anarchism Chapter Four: Organisation Foreword 25 Introduction 196 1. Problems in Writing Anarchist Histories 26 1. Anti-Organisation 200 2. Origins 29 2. Formal Structures: Leninist organisation 212 3. The Heroic Period: A history of British anarchism up to 1914 30 3. Contemporary Anarchist Structures 219 4. Anarchism During the First World War, 1914 - 1918 45 4. Workplace Organisation 234 5. The Decline of Anarchism and the Rise of the 5. Community Organisation 247 Leninist Model, 1918 1936 46 6. Summation 258 6. Decay of Working Class Organisations: The Spani8h Civil War to the Hungarian Revolution, 1936 - 1956 49 Chapter Five: Anarchist Tactics Spring and Fall of the New Left, 7. -

Inceorganisinganarchy2010.Pdf

ORGANISING ANARCHY SPATIAL STRATEGY , PREFIGURATION , AND THE POLITICS OF EVERYDAY LIFE ANTHONY JAMES ELLIOT INCE THESIS SUBMITTED FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY DEPARTMENT OF GEOGRAPHY QUEEN MARY , UNIVERSITY OF LONDON 2010 0 ABSTRACT This research is an analysis of efforts to develop a politics of everyday life through embedding anarchist and left-libertarian ideas and practices into community and workplace organisation. It investigates everyday life as a key terrain of political engagement, interrogating the everyday spatial strategies of two emerging forms of radical politics. The community dimension of the research focuses on two London-based social centre collectives, understood as community-based, anarchist-run political spaces. The Industrial Workers of the World (IWW), an international trade union that organises along radical left-libertarian principles, comprises the workplace element. The empirical research was conducted primarily through an activist-ethnographic methodology. Based in a politically-engaged framework, the research opens up debates surrounding the role of place-based class politics in a globalised world, and how such efforts can contribute to our understanding of social relations, place, networks, and political mobilisation and transformation. The research thus contributes to and provides new perspectives on understanding and enacting everyday spatial strategies. Utilising Marxist and anarchist thought, the research develops a distinctive theoretical framework that draws inspiration from both perspectives. Through an emphasis on how groups seek to implement particular radical principles, the research also explores the complex interactions between theory and practice in radical politics. I argue that it is in everyday spaces and practices where we find the most powerful sources for political transformation. -

Anarchists in the Late 1990S, Was Varied, Imaginative and Often Very Angry

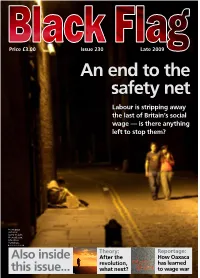

Price £3.00 Issue 230 Late 2009 An end to the safety net Labour is stripping away the last of Britain’s social wage — is there anything left to stop them? Front page pictures: Garry Knight, Photos8.com, Libertinus Yomango, Theory: Reportage: Also inside After the How Oaxaca revolution, has learned this issue... what next? to wage war Editorial Welcome to issue 230 of Black Flag, the fifth published by the current Editorial Collective. Since our re-launch in October 2007 feedback has generally tended to be positive. Black Flag continues to be published twice a year, and we are still aiming to become quarterly. However, this is easier said than done as we are a small group. So at this juncture, we make our usual appeal for articles, more bodies to get physically involved, and yes, financial donations would be more than welcome! This issue also coincides with the 25th anniversary of the Anarchist Bookfair – arguably the longest running and largest in the world? It is certainly the biggest date in the UK anarchist calendar. To celebrate the event we have included an article written by organisers past and present, which it is hoped will form the kernel of a general history of the event from its beginnings in the Autonomy Club. Well done and thank you to all those who have made this event possible over the years, we all have Walk this way: The Black Flag ladybird finds it can be hard going to balance trying many fond memories. to organise while keeping yourself safe – but it’s worth it. -

The New Anarchists

A Movement of Movements?—5 david graeber THE NEW ANARCHISTS t’s hard to think of another time when there has been such a gulf between intellectuals and activists; between theorists of Irevolution and its practitioners. Writers who for years have been publishing essays that sound like position papers for vast social movements that do not in fact exist seem seized with confusion or worse, dismissive contempt, now that real ones are everywhere emerging. It’s particularly scandalous in the case of what’s still, for no particularly good reason, referred to as the ‘anti-globalization’ movement, one that has in a mere two or three years managed to transform completely the sense of historical possibilities for millions across the planet. This may be the result of sheer ignorance, or of relying on what might be gleaned from such overtly hostile sources as the New York Times; then again, most of what’s written even in progressive outlets seems largely to miss the point—or at least, rarely focuses on what participants in the movement really think is most important about it. As an anthropologist and active participant—particularly in the more radical, direct-action end of the movement—I may be able to clear up some common points of misunderstanding; but the news may not be gratefully received. Much of the hesitation, I suspect, lies in the reluc- tance of those who have long fancied themselves radicals of some sort to come to terms with the fact that they are really liberals: interested in expanding individual freedoms and pursuing social justice, but not in ways that would seriously challenge the existence of reigning institu- tions like capital or state. -

Changing Anarchism.Pdf

Changing anarchism Changing anarchism Anarchist theory and practice in a global age edited by Jonathan Purkis and James Bowen Manchester University Press Manchester and New York distributed exclusively in the USA by Palgrave Copyright © Manchester University Press 2004 While copyright in the volume as a whole is vested in Manchester University Press, copyright in individual chapters belongs to their respective authors. This electronic version has been made freely available under a Creative Commons (CC-BY-NC- ND) licence, which permits non-commercial use, distribution and reproduction provided the author(s) and Manchester University Press are fully cited and no modifications or adaptations are made. Details of the licence can be viewed at https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/3.0/ Published by Manchester University Press Oxford Road, Manchester M13 9NR, UK and Room 400, 175 Fifth Avenue, New York, NY 10010, USA www.manchesteruniversitypress.co.uk British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data applied for ISBN 0 7190 6694 8 hardback First published 2004 13 12 11 10 09 08 07 06 05 04 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 Typeset in Sabon with Gill Sans display by Servis Filmsetting Ltd, Manchester Printed in Great Britain by CPI, Bath Dedicated to the memory of John Moore, who died suddenly while this book was in production. His lively, innovative and pioneering contributions to anarchist theory and practice will be greatly missed. -

Get the Goods!

RESISTANCE anarchist paper free/donation issue 113 june 2009 OCCUPATIONS GET THE GOODS! he three Visteon plants have ended their occupation and pickets, following the agreement Tof improved redundancy packages. The dispute came out of the immediate sacking of all UK Visteon workers with no further payment, and instructions to return the next day to collect any belongings. As the company had fi led for administration, only statutory redundancy from the government would be available, a paltry amount for people who are approaching the end of their working life and would be considered unemployable. Workers in Belfast decided to take action, occupying their factory on the 31st March, with workers in Basildon and Enfi eld following suit on 1st April, although they had to end their occupation and settle for pickets a few weeks later. Visteon were eager to distance themselves from Ford, havingcontinued offi cially become inside a separate ►company in 2000. In reality, the ties were still there with staff on mirror contracts and carried Ford identifi cation, and Ford secured Visteon a $163 million loan on May 15th. CONTINUED INSIDE ► INSIDE: ID CARDS, MPS’ EXPENSES, POLICE BRUTALITY AND MORE! 2 paper of the anarchist federation ► CONTINUED FROM FRONT PAGE ON THE While this is a victory, the workers still reinstated, he was again dismissed, and face other struggles. Their pensions are workers were warned to not repeat any FRONTLINE: still very much up in the air, likely to be solidarity action, being threatened with WORKPLACE ROUNDUP going into the Pension Protection Fund, the sack by foremen. which would mean less money; accord- This is a victory against job cuts, a ing to some in Basildon, as much as struggle fought across different parts of •Parking attendants sacked for 40% less. -

Squatted Social Centres in England and Italy in the Last Decades of the Twentieth Century

Squatted social centres in England and Italy in the last decades of the twentieth century. Giulio D’Errico Thesis submitted for the degree of PhD Department of History and Welsh History Aberystwyth University 2019 Abstract This work examines the parallel developments of squatted social centres in Bristol, London, Milan and Rome in depth, covering the last two decades of the twentieth century. They are considered here as a by-product of the emergence of neo-liberalism. Too often studied in the present tense, social centres are analysed here from a diachronic point of view as context- dependent responses to evolving global stimuli. Their ‗journey through time‘ is inscribed within the different English and Italian traditions of radical politics and oppositional cultures. Social centres are thus a particularly interesting site for the development of interdependency relationships – however conflictual – between these traditions. The innovations brought forward by post-modernism and neo-liberalism are reflected in the centres‘ activities and modalities of ‗social‘ mobilisation. However, centres also voice a radical attitude towards such innovation, embodied in the concepts of autogestione and Do-it-Yourself ethics, but also through the reinstatement of a classist approach within youth politics. Comparing the structured and ambitious Italian centres to the more informal and rarefied English scene allows for commonalities and differences to stand out and enlighten each other. The individuation of common trends and reciprocal exchanges helps to smooth out the initial stark contrast between local scenes. In turn, it also allows for the identification of context- based specificities in the interpretation of local and global phenomena. -

International Medical Corps Afghanistan

Heading Folder Afghanistan Afghanistan - Afghan Information Centre Afghanistan - International Medical Corps Afghanistan - Revolutionary Association of the Women of Afghanistan (RAWA) Agorist Institute Albee, Edward Alianza Federal de Pueblos Libres American Economic Association American Economic Society American Fund for Public Service, Inc. American Independent Party American Party (1897) American Political Science Association (APSA) American Social History Project American Spectator American Writer's Congress, New York City, October 9-12, 1981 Americans for Democratic Action Americans for Democratic Action - Students for Democractic Action Anarchism Anarchism - A Distribution Anarchism - Abad De Santillan, Diego Anarchism - Abbey, Edward Anarchism - Abolafia, Louis Anarchism - ABRUPT Anarchism - Acharya, M. P. T. Anarchism - ACRATA Anarchism - Action Resource Guide (ARG) Anarchism - Addresses Anarchism - Affinity Group of Evolutionary Anarchists Anarchism - Africa Anarchism - Aftershock Alliance Anarchism - Against Sleep and Nightmare Anarchism - Agitazione, Ancona, Italy Anarchism - AK Press Anarchism - Albertini, Henry (Enrico) Anarchism - Aldred, Guy Anarchism - Alliance for Anarchist Determination, The (TAFAD) Anarchism - Alliance Ouvriere Anarchiste Anarchism - Altgeld Centenary Committee of Illinois Anarchism - Altgeld, John P. Anarchism - Amateur Press Association Anarchism - American Anarchist Federated Commune Soviets Anarchism - American Federation of Anarchists Anarchism - American Freethought Tract Society Anarchism - Anarchist -

In the Social Factory? Immaterial Labour, Precariousness and Cultural Work

026 Issue # 16/13 : THE PRECARIOUS LABOUR IN THE FIELD OF ART PRECARITY AND CULTURAL WORK IN THE SOCIAL FACTORY? IMMATERIAL LABOUR, PRECARIOUSNESS AND CULTURAL WORK Rosalind Gill and Andy Pratt Transformations in advanced capitalism under the impact of globalization, information and communication technologies, and changing modes of political and economic governance have produced an apparently novel situation in which increasing numbers of workers in affluent societies are engaged in insecure, casualized or irregular labour. While capita- list labour has always been characterized by intermittency for lower-paid and lower- skilled workers, the recent departure is the addition of well-paid and high-status workers into this group of 'precarious workers'. The last decades have seen a variety of attempts to make sense of the broad changes in contemporary capitalism that have given rise to this – through discussions of shifts relating to post-Fordism, post-industri- alization, network society, liquid modernity, information society, 'new economy', 'new capitalism' and risk society (see Bauman, 2000, 2005; Beck, 2000; Beck and Ritter, 1992; Beck et al., 2000; Bell, 1973; Boltanski and Chiapello, 2005; Castells, 1996; Lash and Urry, 1993; Reich, 2000; Sennett, 1998, 2006; Theory, Culture & Society has also been an important forum for these debates). While work has been central to all these accounts, the relationship between the transformations within working life and workers' subjec- tivities has been relatively under-explored. However, in the last few years a number of terms have been developed that appear to speak directly to this. Notions include crea- tive labour, network labour, cognitive labour, affective labour and immaterial labour. -

Tactics: Conceptions of Social Change, Revolution, and Anarchist Organisation

CHAPTER 6 Tactics: Conceptions of Social Change, Revolution, and Anarchist Organisation Dana M. Williams INTRODUCTiON Social movement tactics are all the things that movement participants do to achieve larger goals. In the day-to-day pursuit of goals, tactics fit into the gen- eral framework of a movement’s strategy. If strategy is the broad organising plans for accomplishing goals, then tactics are the specific actions or techniques through which strategies are implemented.1 Considered together, multiple tac- tics compose a protest repertoire2: the temporal, spatial, and cultural patterning of protest tactics into a toolkit of established approaches that movement partici- pants use. Repertoires enable and often limit what people can do, although they do not guarantee any kind of action. Thus, repertoires are probabilistic, not deterministic. All the tactics within anarchist movement repertoires dis- cussed below presumably contribute to the acquisition of anarchist goals and a more anarchistic future. However, anarchist movement tactics do no need to be deployed only by self-conscious anarchists; others can utilise ‘anarchistic’ tactics which sharply mirror those wielded by anarchists themselves. Anarchist tactics aim to accomplish two things simultaneously. First, they oppose things that anarchists considered to be bad, such as hierarchy, repres- sion, and inequality. In this respect, tactics serve a diagnostic function that negatively frames societal characteristics with an anarchist analysis. Second, anarchist tactics promote things that anarchists consider to be good, like hori- zontal relationships, liberation, and egalitarianism. Thus, tactics are also prog- nostic frames that suggest better, more positive forms of social organisation. D. M. Williams (*) Department of Sociology, California State University, Chico, CA, USA e-mail: [email protected] © The Author(s) 2019 107 C. -

Organising Anarchy Spatial Strategy Prefiguration and the Politics of Everyday Life Ince, Anthony James Elliot

Organising anarchy spatial strategy prefiguration and the politics of everyday life Ince, Anthony James Elliot The copyright of this thesis rests with the author and no quotation from it or information derived from it may be published without the prior written consent of the author For additional information about this publication click this link. https://qmro.qmul.ac.uk/jspui/handle/123456789/496 Information about this research object was correct at the time of download; we occasionally make corrections to records, please therefore check the published record when citing. For more information contact [email protected] ORGANISING ANARCHY SPATIAL STRATEGY , PREFIGURATION , AND THE POLITICS OF EVERYDAY LIFE ANTHONY JAMES ELLIOT INCE THESIS SUBMITTED FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY DEPARTMENT OF GEOGRAPHY QUEEN MARY , UNIVERSITY OF LONDON 2010 0 ABSTRACT This research is an analysis of efforts to develop a politics of everyday life through embedding anarchist and left-libertarian ideas and practices into community and workplace organisation. It investigates everyday life as a key terrain of political engagement, interrogating the everyday spatial strategies of two emerging forms of radical politics. The community dimension of the research focuses on two London-based social centre collectives, understood as community-based, anarchist-run political spaces. The Industrial Workers of the World (IWW), an international trade union that organises along radical left-libertarian principles, comprises the workplace element. The empirical research was conducted primarily through an activist-ethnographic methodology. Based in a politically-engaged framework, the research opens up debates surrounding the role of place-based class politics in a globalised world, and how such efforts can contribute to our understanding of social relations, place, networks, and political mobilisation and transformation. -

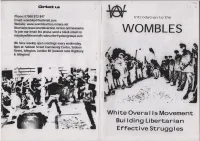

Introduction to the WOMBLES

J 1 : '_,--- 847 introdutnon to the Email: [email protected] eeiebsite: eaction.mrnice.net Newswire:www.womb reaction.mtrnice.netlnewswire Tojoin uremail listp ease send a blank emaii to: i emaydaa» aihiteoveralls-subscribe@yaho0groupsxom -.___..--_ \ = e have weekly open meetings every wednesday, 8pm at: Sebon Street fiommunity Centre, ebbon 4"“---__-I---|---.+___ Street, elsiington, Lorndrl N1 [nearest tube Highbury -I-“-—‘-4--L-._._____ & lslington] -—..-..,_- i' _| *3‘: —:*-— "" 0 '4. —n---...,__,_,.___ . '-|. ,_ A _ __ _ " -_. -- -._4:. - >-_. -- .. -I.--.1—_;-._.. - , _ ' - ;'_—“;-.; '- __ _. " I .| _ I ? I "‘ ll.“-1--__-. ' - I ' . ?- ch ' '-".1-=-'".' ;.. -.,', J. 0- . ___, ' '.i-_..-.'-' - _ - ei? é. fix “ii fig?” -5 »4;_,i___ -—-—..-|_ . .1’ - , Q‘ ". 1 "‘ * 7;-'1' ., *.\'=,..-I .1}. - '- ___ J .fl.ib- I'M ¢- I ' . _ ~| -' "r _ 1--.' . ---=.- ._ ¢_ ' ' -c .- * * '-"*"""'i€'*l-wt-11* =|--:- - ' - ".- "E --.-1 . , '5:-v - 4 - " .. _' '. ' I" Z‘- ~— -It ' “ ' I‘ .. ; ' - \ .' '- u mi‘-' _ - ‘:-: :5:-:5-___ .:._.\ -"~:. 1-"I .,,-2» _: I». u _, _-,,. -J ‘5'-- $ E.‘ $1‘ 5“ I ' .. \ I i If. It '- - r I Ie -‘:5-',-, - 2.... ----. -3,.‘ -'-.4.3!/%3.g'.-. I"\ I-1'\ 4'“. ii‘ g "1 tee ._._-__ _,-Lari; ,_ -1 '1 ‘ E -H - -' - -'.'_--. '1' *1!‘ "1 1' ,_ .J_.|‘I _|‘" ‘,_._ __\_. _-_ H’ I I I _ - . _-\_!:i I "trek ' ..-. -_- "\'--'-- ¢~=.=--c. 1..-.-'-"‘1 ~ '_:-- %i-_ .-..-'. -1_.- _ . _ .' 1 ""-"-"""_* '-r--" -' .- '5 m '_': ".-'F--- ' --- - --. -.--.- ' -I.‘--' -.7‘; -l-—"- - *-"-1-. -.».-' ' "' ' " -' =- ‘-~.-J--‘ - "7-"""'-"-1' '5""—'_" .. J‘ .*' * """' White Overa I ls Movement --.+--5,-.