The Islamization of Pakistan, 1979-2009

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Pakistan: Death Plot Against Human Rights Lawyer, Asma Jahangir

UA: 164/12 Index: ASA 33/008/2012 Pakistan Date: 7 June 2012 URGENT ACTION DEATH PLOT AGAINST HUMAN RIGHTS LAWYER Leading human rights lawyer and activist Asma Jahangir fears for her life, having just learned of a plot by Pakistan’s security forces to kill her. Killings of human rights defenders have increased over the last year, many of which implicate Pakistan’s Inter- Service Intelligence agency (ISI). On 4 June, the Human Rights Commission of Pakistan (HRCP) alerted Amnesty International to information it had received of a plot by Pakistan’s security forces to kill HRCP founder and human rights lawyer Asma Jahangir. As Pakistan’s leading human rights defender, Asma Jahangir has been threatened many times before. However news of the plot to kill her is altogether different. The information available does not appear to have been intentionally circulated as means of intimidation, but leaked from within Pakistan’s security apparatus. Because of this, Asma Jahangir believes the information is highly credible and has therefore not moved from her home. Please write immediately in English, Urdu, or your own language, calling on the Pakistan authorities to: Immediately provide effective security to Asma Jahangir. Promptly conduct a full investigation into alleged plot to kill her, including all individuals and institutions suspected of being involved, including the Inter-Services Intelligence agency. Bring to justice all suspected perpetrators of attacks on human rights defenders, in trials that meet international fair trial standards and -

Download Article

Pakistan’s ‘Mainstreaming’ Jihadis Vinay Kaura, Aparna Pande The emergence of the religious right-wing as a formidable political force in Pakistan seems to be an outcome of direct and indirect patron- age of the dominant military over the years. Ever since the creation of the Islamic Republic of Pakistan in 1947, the military establishment has formed a quasi alliance with the conservative religious elements who define a strongly Islamic identity for the country. The alliance has provided Islamism with regional perspectives and encouraged it to exploit the concept of jihad. This trend found its most obvious man- ifestation through the Afghan War. Due to the centrality of Islam in Pakistan’s national identity, secular leaders and groups find it extreme- ly difficult to create a national consensus against groups that describe themselves as soldiers of Islam. Using two case studies, the article ar- gues that political survival of both the military and the radical Islamist parties is based on their tacit understanding. It contends that without de-radicalisation of jihadis, the efforts to ‘mainstream’ them through the electoral process have huge implications for Pakistan’s political sys- tem as well as for prospects of regional peace. Keywords: Islamist, Jihadist, Red Mosque, Taliban, blasphemy, ISI, TLP, Musharraf, Afghanistan Introduction In the last two decades, the relationship between the Islamic faith and political power has emerged as an interesting field of political anal- ysis. Particularly after the revival of the Taliban and the rise of ISIS, Author. Article. Central European Journal of International and Security Studies 14, no. 4: 51–73. -

ISI in Pakistan's Domestic Politics

ISI in Pakistan’s Domestic Politics: An Assessment Jyoti M. Pathania D WA LAN RFA OR RE F S E T Abstract R U T D The articleN showcases a larger-than-life image of Pakistan’s IntelligenceIE agencies Ehighlighting their role in the domestic politics of Pakistan,S C by understanding the Inter-Service Agencies (ISI), objectives and machinations as well as their domestic political role play. This is primarily carried out by subverting the political system through various means, with the larger aim of ensuring an unchallenged Army rule. In the present times, meddling, muddling and messing in, the domestic affairs of the Pakistani Government falls in their charter of duties, under the rubric of maintenance of national security. Its extra constitutional and extraordinary powers have undoubtedlyCLAWS made it the potent symbol of the ‘Deep State’. V IC ON TO ISI RY H V Introduction THROUG The incessant role of the Pakistan’s intelligence agencies, especially the Inter-Service Intelligence (ISI), in domestic politics is a well-known fact and it continues to increase day by day with regime after regime. An in- depth understanding of the subject entails studying the objectives and machinations, and their role play in the domestic politics. Dr. Jyoti M. Pathania is Senior Fellow at the Centre for Land Warfare Studies, New Delhi. She is also the Chairman of CLAWS Outreach Programme. 154 CLAWS Journal l Winter 2020 ISI IN PAKISTAN’S DOMESTIC POLITICS ISI is the main branch of the Intelligence agencies, charged with coordinating intelligence among the -

Revisit to Dhaka University As the Symbol of Bengal Partition Sowmit Chandra Chanda Dr

Academic Ramification in Colonial India: Revisit to Dhaka University as the Symbol of Bengal Partition Sowmit Chandra Chanda Dr. Neerja A. Gupta PhD Research Scholar under Dr. Neerja A. Director & Coordinator, Department of Gupta, Department of Diaspora and Diaspora and Migration Studies, SAP, Migration Studies, SAP, Gujarat Gujarat University, Ahmedabad, India. University, Ahmedabad, India. Abstract: It has been almost hundred years since University of Dhaka was established back in 1921. It was the 13th University built in India under the Colonial rule. It was that like of dream comes true object for those people who lived in the eastern part of Indian Sub-continent under Bengal presidency in the British period. But when the Bengal partition came into act in 1905, people from the new province of East Bengal and Assam were expecting a faster move from the government to establish a university in their capital city. But, with in 6 years, the partition was annulled. The people from the eastern part was very much disappointed for that, but they never left that demand to have a university in Dhaka. After some several reports and commissions the university was formed at last. But, in 1923, in the first convocation of the university, the chancellor Lord Lytton said this university was given to East Bengal as a ‘splendid Imperial compensation’. Which turns our attention to write this paper. If the statement of Lytton was true and honest, then certainly Dhaka University stands as the foremost symbol of both the Bengal Partition in the academic ramification. Key Words: Partition, Bengal Partition, Colony, Colonial Power, Curzon, University, Dhaka University etc. -

1 All Rights Reserved Do Not Reproduce in Any Form Or

ALL RIGHTS RESERVED DO NOT REPRODUCE IN ANY FORM OR QUOTE WITHOUT AUTHOR’S PERMISSION 1 2 Tactical Cities: Negotiating Violence in Karachi, Pakistan by Huma Yusuf A.B. English and American Literature and Language Harvard University, 2002 SUBMITTED TO THE DEPARTMENT OF COMPARATIVE MEDIA STUDIES IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF SCIENCE IN COMPARATIVE MEDIA STUDIES AT THE MASSACHUSETTS INSTITUTE OF TECHNOLOGY JUNE 2008 © Huma Yusuf. All rights reserved. The author hereby grants to MIT permission to reproduce and to distribute publicly paper and electronic copies of this thesis document in whole or in part in any medium now known or hereafter created. Thesis Supervisor: ________________________________________________________ Henry Jenkins Peter de Florez Professor of Humanities Professor of Comparative Media Studies and Literature Thesis Supervisor: ________________________________________________________ Shankar Raman Associate Professor of Literature Thesis Supervisor: ________________________________________________________ William Charles Uricchio Professor of Comparative Media Studies 3 4 Tactical Cities: Negotiating Violence in Karachi, Pakistan by Huma Yusuf Submitted to the Department of Comparative Media Studies on May 9, 2008, in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master in Science in Comparative Media Studies. ABSTRACT This thesis examines the relationship between violence and urbanity. Using Karachi, Pakistan, as a case study, it asks how violent cities are imagined and experienced by their residents. The thesis draws on a variety of theoretical and epistemological frameworks from urban studies to analyze the social and historical processes of urbanization that have led to the perception of Karachi as a city of violence. It then uses the distinction that Michel de Certeau draws between strategy and tactic in his seminal work The Practice of Everyday Life to analyze how Karachiites inhabit, imagine, and invent their city in the midst of – and in spite of – ongoing urban violence. -

The Opposition of a Leading Akhund to Shi'a and Sufi

The Opposition of a Leading Akhund to Shi’a and Sufi Shaykhs in Mid-Nineteenth- Century China Wang Jianping, Shanghai Normal University Abstract This article traces the activities of Ma Dexin, a preeminent Hui Muslim scholar and grand imam (akhund) who played a leading role in the Muslim uprising in Yunnan (1856–1873). Ma harshly criticized Shi’ism and its followers, the shaykhs, in the Sufi orders in China. The intolerance of orthodox Sunnis toward Shi’ism can be explained in part by the marginalization of Hui Muslims in China and their attempts to unite and defend themselves in a society dominated by Han Chinese. An analysis of the Sunni opposition to Shi’ism that was led by Akhund Ma Dexin and the Shi’a sect’s influence among the Sufis in China help us understand the ways in which global debates in Islam were articulated on Chinese soil. Keywords: Ma Dexin, Shi’a, shaykh, Chinese Islam, Hui Muslims Most of the more than twenty-three million Muslims in China are Sunnis who follow Hanafi jurisprudence when applying Islamic law (shariʿa). Presently, only a very small percentage (less than 1 percent) of Chinese Muslims are Shi’a.1 The historian Raphael Israeli explicitly analyzes the profound impact of Persian Shi’ism on the Sufi orders in China based on the historical development and doctrinal teachings of Chinese Muslims (2002, 147–167). The question of Shi’a influence explored in this article concerns why Ma Dexin, a preeminent Chinese Muslim scholar, a great imam, and one of the key leaders of the Muslim uprising in the nineteenth century, so harshly criticized Shi’ism and its accomplices, the shaykhs, in certain Sufi orders in China, even though Shi’a Islam was nearly invisible at that time. -

Chinese Policy Towards Pakistan, 1969-1979

CHINESE POLICY TOWARDS PAKISTAN (1969 - 1979) by Samina Yasmeen Submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of Tasmania April 1985 CONTENTS INTHODUCTION 1 PART ONE CHAPTER I 7 CHINESE POLICY TOWARDS PAKISTAN DURING THE 1950s 7 CHAPTER II 31 CHINESE POLICY TOWARDS PAKISTAN DURING THE 1960-68 PERIOD 31 Keeping the Options Open 31 Cautious Move to Friendship 35 Consolidation of a Friendship 38 The Indo-Pakistan War (1965) and China 63 The Post-War Years 70 Conclusion 72 PART TWO CHAPTER III 74 FROM UNQUALIFIED TO QUALIFIED SUP PORT: THE KASJ-IMIIl DISPUTE 75 China and the Kashmir Issue: 1969-1971 76 The Bhutto Regime - The Kashmir Issue and China 85 The Zia Regime - The Kashmir Issue and China 101 CHAPTER IV FROM QUALIFIED TO UNQUALIFIED SUPPORT: EAST PAKISTAN CRISIS (1971) 105 The Crisis - India, Pakistan and China's Initial Reaction 109 Continuation of a Qualified Support 118 A Change in Support: Qualified to Unqualified 129 Conclusion 138 CHAPTER V 140 UNQUALIFIED SUPPORT: CHINA AND THE 'NEW' PAKISTAN'S PROBLEMS DECEMBER 1971-APRIL 1974 140 Pakistan's Problems 141 Chinese Support for Pakistan 149 Significance of Chinese Support 167 Conclusion 17 4 CHAPTER VI 175 CAUTION AMIDST CONTINUITY: CHINA, THE INDIAN NUCLEAR TEST AND A PROPOSED NUCLEAR FREE SOUTH ASIA 175 Indian Nuclear Explosion 176 Nuclear-Free Zone in South Asia 190 Conclusion 199 CHAPTER VII 201 PAKISTAN AND THE SAUR REVOLUTION IN AFGHANISTAN (1978): CHINESE RESPONSES 201 The Saur Revolution and Pakistan's Threat Perceptions -

Newsletter – April 2008

Newsletter – April 2008 Syed Yousaf Raza Gillani sworn in as Hon. Dr Fahmida Mirza takes her seat th 24 Prime Minister of Pakistan as Pakistan’s first woman Speaker On 24 March Syed Yousaf A former doctor made history Raza Gillani was elected in Pakistan on 19 March by as the Leader of the becoming the first woman to House by the National be elected Speaker in the Assembly of Pakistan and National Assembly of the next day he was Pakistan. Fahmida Mirza won sworn in as the 24th 249 votes in the 342-seat Lower House of parliament. Prime Minister of Pakistan. “I am honoured and humbled; this chair carries a big Born on 9 June 1952 in responsibility. I am feeling that responsibility today and Karachi, Gillani hails from will, God willing, come up to expectations.” Multan in southern Punjab and belongs to a As Speaker, she is second in the line of succession to prominent political family. His grandfather and the President and occupies fourth position in the Warrant grand-uncles joined the All India Muslim League of Precedence, after the President, the Prime Minister and were signatories of the historical Pakistan and the Chairman of Senate. Resolution passed on 23 March 1940. Mr Gillani’s father, Alamdar Hussain Gillani served as a Elected three times to parliament, she is one of the few Provincial Minister in the 1950s. women to have been voted in on a general seat rather than one reserved for women. Mr Yousaf Raza Gillani joined politics at the national level in 1978 when he became a member Fahmida Mirza 51, hails from Badin in Sindh and has of the Muslim League’s central leadership. -

Shiism and Sectarian Conflict in Pakistan Identity Politics, Iranian Influence, and Tit-For-Tat Violence

Combating Terrorism Center at West Point Occasional Paper Series Shiism and Sectarian Conflict in Pakistan Identity Politics, Iranian Influence, and Tit-for-Tat Violence Hassan Abbas September 22, 2010 1 2 Preface As the first decade of the 21st century nears its end, issues surrounding militancy among the Shi‛a community in the Shi‛a heartland and beyond continue to occupy scholars and policymakers. During the past year, Iran has continued its efforts to extend its influence abroad by strengthening strategic ties with key players in international affairs, including Brazil and Turkey. Iran also continues to defy the international community through its tenacious pursuit of a nuclear program. The Lebanese Shi‛a militant group Hizballah, meanwhile, persists in its efforts to expand its regional role while stockpiling ever more advanced weapons. Sectarian violence between Sunnis and Shi‛a has escalated in places like Saudi Arabia, Yemen, Bahrain, and not least, Pakistan. As a hotbed of violent extremism, Pakistan, along with its Afghan neighbor, has lately received unprecedented amounts of attention among academics and policymakers alike. While the vast majority of contemporary analysis on Pakistan focuses on Sunni extremist groups such as the Pakistani Taliban or the Haqqani Network—arguably the main threat to domestic and regional security emanating from within Pakistan’s border—sectarian tensions in this country have attracted relatively little scholarship to date. Mindful that activities involving Shi‛i state and non-state actors have the potential to affect U.S. national security interests, the Combating Terrorism Center is therefore proud to release this latest installment of its Occasional Paper Series, Shiism and Sectarian Conflict in Pakistan: Identity Politics, Iranian Influence, and Tit-for-Tat Violence, by Dr. -

Announced on Monday, July 19, 2021

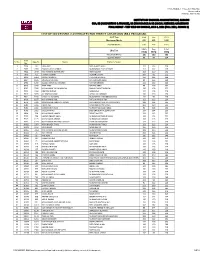

FINAL RESULT - FALL 2021 ROUND 2 Announced on Monday, July 19, 2021 INSTITUTE OF BUSINESS ADMINISTRATION, KARACHI BBA, BS (ACCOUNTING & FINANCE), BS (ECONOMICS) & BS (SOCIAL SCIENCES) ADMISSIONS FINAL RESULT ‐ TEST HELD ON SUNDAY, JULY 4, 2021 (FALL 2021, ROUND 2) LIST OF SUCCESSFUL CANDIDATES FOR DIRECT ADMISSION (BBA PROGRAM) SAT Test Math Eng TOTAL Maximum Marks 800 800 1600 Cut-Off Marks 600 600 1420 Math Eng Total IBA Test MCQ MCQ MCQ Maximum Marks 180 180 360 Cut-Off Marks 88 88 224 Seat S. No. App No. Name Father's Name No. 1 7904 30 LAIBA RAZI RAZI AHMED JALALI 112 116 228 2 7957 2959 HASSAAN RAZA CHINOY MUHAMMAD RAZA CHINOY 112 132 244 3 7962 3549 MUHAMMAD SHAYAN ARIF ARIF HUSSAIN 152 120 272 4 7979 455 FATIMA RIZWAN RIZWAN SATTAR 160 92 252 5 8000 1464 MOOSA SHERGILL FARZAND SHERGILL 124 124 248 6 8937 1195 ANAUSHEY BATOOL ATTA HUSSAIN SHAH 92 156 248 7 8938 1200 BIZZAL FARHAN ALI MEMON FARHAN MEMON 112 112 224 8 8978 2248 AFRA ABRO NAVEED ABRO 96 136 232 9 8982 2306 MUHAMMAD TALHA MEMON SHAHID PARVEZ MEMON 136 136 272 10 9003 3266 NIRDOSH KUMAR NARAIN NA 120 108 228 11 9017 3635 ALI SHAZ KARMANI IMTIAZ ALI KARMANI 136 100 236 12 9031 1945 SAIFULLAH SOOMRO MUHAMMAD IBRAHIM SOOMRO 132 96 228 13 9469 1187 MUHAMMAD ADIL RAFIQ AHMAD KHAN 112 112 224 14 9579 2321 MOHAMMAD ABDULLAH KUNDI MOHAMMAD ASGHAR KHAN KUNDI 100 124 224 15 9582 2346 ADINA ASIF MALIK MOHAMMAD ASIF 104 120 224 16 9586 2566 SAMAMA BIN ASAD MUHAMMAD ASAD IQBAL 96 128 224 17 9598 2685 SYED ZAFAR ALI SYED SHAUKAT HUSSAIN SHAH 124 104 228 18 9684 526 MUHAMMAD HAMZA -

Citizenship Govnerment

CITIZENSHIP GOVERNANCE The Citizenship Amendment Bill (CAA Bill) was first introduced in 2016 in Lok Sabha by amending the Citizenship Act of 1955. This bill was referred to a Joint Parliamentary Committee, whose report was later submitted on January 7, 2019. The Citizenship Amendment Bill was passed on January 8, 2019, by the Lok Sabha which lapsed with the dissolution of the 16th Lok Sabha. This Bill was introduced again on 9 December 2019 by the Minister of Home Affairs Amit Shah in the 17th Lok Sabha and was later passed on 10 December 2019. The Rajya Sabha also passed the bill on 11th December. The CAA was passed to provide Indian citizenship to the illegal migrants who entered India on or before 31st December 2014. The Act was passed for migrants of six different religions such as Hindus, Sikhs, Buddhists, Jains, Parsis, and Christians from Afghanistan, Bangladesh, and Pakistan. Any individual will be considered eligible for this act if he/she has resided in India during the last 12 months and for 11 of the previous 14 years. For the specified class of illegal migrants, the number of years of residency has been relaxed from 11 years to five years. CAA 2019 Citizenship Amendment Bill 2019 gets Parliament’s nod. What is Citizenship? Citizenship defines the relationship between the nation and the people who constitute the nation. It confers upon an individual certain rights such as protection by the state, right to vote, and right to hold certain public offices, among others, in return for the fulfillment of certain duties/obligations owed by the individual to the state. -

List of Candidates Who Applied for Nursery Admissions 2013-14 Reg

HAMDARD PRIMARY SCHOOL (OKHLA) List of candidates who applied for Nursery admissions 2013-14 Reg. Remarks of the verification Form Name of Student Father's Name deparmtment or Admission Cases Total Single Parent No. Gender Siblings Siblings Alumini Alumini Deparmtment Muslims Muslims Distance Transfer 1 FARHAN IQBAL QUAISER IQBAL M 25 - - - - 20 45 2 KASHAAN KHAN ADIB KHAN M 25 - - - - 20 45 3 SAMAN KHAN MUNSHAD KHAN F 25 - - - - 20 45 4 ZUNAIRA SHAKEEL SHAKEEL AHMAD F 25 25 - - - 20 70 5 MUSTAFA JAMAL KOSAR JAMAL KHAN M 25 - - - - 20 45 6 TABSUM FATMA MD. NAUSHAD F 25 - - - - 20 45 7 NUMAIR KHAN ASRAR HUSSAIN KHAN M 25 - - - - 20 45 8 SHIPRA BEHURA SRIKANT KUMAR BEHURA F 25 - 10 - - - 35 9 SAMAKSHYA BEHURA SRIKANT KUMAR BEHURA M 25 - - - - - 25 Proof of Single Parent Not Given 10 HITEN BEHURA HEMENT BEHURA M R R R R R R R Invalid Address Proof 12 MOHAMMAD SARHAN MOHAMMAD SUFIYAN M 25 - - - - 20 45 13 MOHD. HABEEB JAMIL QAISAR JAMAL QURAISHI M 25 - - - - 20 45 14 GHULAM WALI IMAM AZHAR IMAM M R R R R R R R Invalid Address Proof 15 SAYED MOHAMMAD ISMAEEL SAYED RIZWANUL HAQUE M 25 - - - - 20 45 16 MOHD. AQIB MOHD. ASIF M 25 - - - - 20 45 17 ILMA ZAFAR HEDAYAT ULLAH ZAFAR F 25 - - - - 20 45 23 KULSUM JAVED SAFDAR JAVED F 25 - - - - 20 45 24 RUBAB FATIMA MOHAMMAD KHURSHEED ALAM F 25 - - - - 20 45 26 MUHAMMAD ABAAN MUHAMMAD ARIF M 25 - - - - 20 45 Transfer Not Applicable 27 MD. SHAFAI MD. FIROJ ALAM M 25 - - - - 20 45 28 ARHAM RAHMAN TANWIR ALAM M R R R R R R R Invalid Address Proof There are total 124 applicants who secured 70 points against 110 seats for nursery for which a draw will be held on 25.02.2013 (Monday) at 12 noon to finalise the selected list of the candidates for admission in Nursery HAMDARD PRIMARY SCHOOL (OKHLA) List of candidates who applied for Nursery admissions 2013-14 Reg.